Banking regulation for sustainable growth

Introduction

Does the after crisis regulation promote a sound banking sector

What reforms for curbing risk taking behavior?

Appendices

Bibliography

Nathalie Janson,

In particular through the Community reinvestment act (1977) and the home Mortgage Disclosure act (hMDa) that aim at granting mortgages to ethnic minorities and low income families.

To find more about how structured products work see Blundell-Wignall 2007 et Cousseran-Rahmouni 2005.

Collateralized Debt obligations (CDOs) create three tranches of income flows corresponding to three classes of thus it can match better the risk preference of investors:

-

- the equity tranche concerns investors with a high preference for risks, they are the first ones to absorb losses in case of default of payment.

- the holders of mezzanine tranche will start to loose money when losses exceed the value of equity investors of that type have a relative preference for risk.

- the holders of senior tranche are not supposed to loose any money unless losses exceed the value of the previous 2 investors of that type have a risk aversion and look for securing their return.

See federal reserve Board and Blundell-wignall 2007, p. 7: the market value of Mortgage Backed securities et CDOs culminated at the end of 2003 at $5 trillion and then decreased to $3 trillion in 2006 and less than $1 trillion at the end of 2007.

According to isDa, Credit Default swaps notional amount reached a record high level of $62,173 billion in 2007 and fell down to $38,564 billion in 2008.

After two dramatic years for the banking sector, in particular after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008, 2009 signs an alt. The worst seems to have been avoided and the financial and banking sector is slowly recovering from one the major crisis since the Great Depression. The epicenter of the crisis was located in the USA but given the leading role played by the US financial markets in recycling international savings, the crisis spread over the globe and led to a deep recession word wild.

The crisis in the USA results from the conjunction of 3 factors:

- The US monetary policy that kept the interest rates at an historically low level (between 1 and 2%) from the end of 2001 and the beginning of 2005, contributing to the development of the real-estate bubble (see appendix 1);

- A strong competition in the banking and financial that led to a change in the banking business model from the traditional “originate to hold” to “originate to distribute” reinforcing the link between banks and the financial markets, in particular the money markets.

- An inadequate banking regulation that led to unintended changes in the business model embraced by banks. Indeed it gave a strong incentive to banks for “securitizing” their balance sheets and developing off-balance sheet activities. Moreover, banking regulation encouraged specifically the development of “subprimes”1 market.

The crisis came as a major crisis of confidence. Investors were no longer able to assess correctly the value of hybrid products like collateralized debt obligation (in particular synthetic ones) created out of Mortgage Backed Securities2 given the opacity of the information characterizing those products. As a matter of fact, the crisis of confidence came from the “subprimes” market as the default of payment started to accumulate at an accelerating rate. Indeed, the securitization of mortgages mixing “primes” and “subprimes” in addition to the creation of complex hybrid products like Collateral Debt Obligation increases the difficulty to trace the “subprimes” products. The incapacity of investors to assess correctly the value of those innovative products found its origin in many reasons. First of all, the assumptions underlying the valuation process of securitized portfolios and hybrid products including “subprimes” products were no longer founded: experts were not capable to up-date their valuation models to the new situation since the “subprimes” market was new and there was no historical data available. Moreover given the complexity of the products created, in particular the “tranching”3 of the securities, as investors started to raise serious doubt about their “true value”, the lack of confidence affected the whole range of “sub- primes” related products and their quote was suspended given the lack of reliable information. This is the reason why markets for Collateral Debt Obligation4 and Credit Derivative Swaps5 collapsed below their “fundamental” value. This collapse was just the result of the incapacity of investors to value correctly those products. Under these circumstances, it came as no surprise when the authorities decided to investigate the rating agencies industry in order to understand the criteria they relied on. Indeed, the day before the collapse, new issues of those products were still rated AAA. In order to prevent the next crisis, the monetary and banking authorities together with the governments decided to join their forces to redesign the banking and financial regulation. But are the current reforms going in the right direction and will they succeed in changing deeply the system in particular curbing the incentive for risk taking? The scope of this paper is to investigate this question.

The current crisis is deeply rooted in an excessive and uncontrolled risk-taking behavior. Therefore the ongoing reforms discussed within the Bank for International Settlements and by most of the governments must curb that behavior otherwise the banking and financial sector will still be prone to other crises. The first part of this paper is dedicated to a critical analysis of the recent decisions of monetary policy taken by the Federal Reserve in order to restore the confidence in the banking system and of the recent propositions made by the Basel Committee to strengthen the stability of the banks and by the US administration, in particular the last plan proposed by the President Obama to restrict the activity and the size of banks protected by the government safety net. Given the limits and the inconsistencies underlined, the second part offers a radical alternative to the current reforms, the final aim being to remedy the negative consequences of the “too big to fail” policy and the weaknesses of the current corporate governance rules prevailing in the banking sector by revisiting the banking history.

Does the after crisis regulation promote a sound banking sector

It is worth underlying the fact that since the implementation of Basel I accord in 1988, the minimum capital requirement of 8% started to be a benchmark in the industry.

The Basel II accord was supposed to be implemented for the 10 biggest commercial banks in the USA shortly after the crisis outbursted.

It is possible to check the changes of the fed balance sheet: in order to be transparent and educational, the fed publishes on its website all the information related to its unconventional monetary policy.

This decision has been taken on February, 18th 2010.

The risk-weighted capital ratio of 8% became a reference for assessing the soundness of a banking institution. in order to reduce the cost of rising new funds in the market, banks had an incentive to hold a capital ratio above that minimum.

Bank 2009.

Transactions on complex products at the root of the crisis take place mainly in the Over the Counter market and this makes difficult to have a precise idea of the size of the market. The data reported are usually estimated data.

Bank 2008.

It is worth reminding that the conditions for implementing the Basel II accord are left to the national authorities. Thus Spain decided to adopt different minima according to the size, the activity of the banking institutions.

« Reforming Banking Camp Basel », The Economist 2010 (1).

The cost of capital is higher than the cost of debt because of the major losses absorbed by this assumption invalidates de facto Modigliani and Miller theorem. In the banking activity, the equivalence theorem does not hold because of the asymmetry of information.

« Reforming Banks: the weakest links », The Economist 2010 (1). The British bank lloyds nationalized in 2008 has been the first bank to issue a “coco bond” for an amount equivalent to 1,6 % of its risk-weighted assets. This bond gives a coupon and becomes capital in order to absorb losses whenever the capital ratio falls below 5% of the risk-weighted assets. Goldman Sachs said it might consider issuing such bonds in the near future.

According to ISDa, Credit Default swaps notional amount went from $919 billion in 2001 to $62,173 billion in 2007, record year. In 2008, his amount went down to $38,564 billion.

« Buttonwood… », The Economist 2010 (2).

The Northern Rock Bank experienced at its own expenses the danger of relying too much on money markets to manage its liquidity. It is worth reminding that this bank had voluntarily reduced the share of deposits in its liabilities substituting them by money market instruments. Therefore as there were raising concerns about its soundness (beginning of 2007), the money markets operators started to no longer trust the quality of its signature and as a result were no longer accepting to refinance it. This led the bank to face illiquidity during summer 2007 and further the panic of September 2007.

On that point, blaming traders for their bonuses accusing them of being the cause of the crisis is like incriminating cars for being the cause of fatal accidents because of the speed at which they can go. Traders take the risks managers and shareholders let them take. The excessive risk taking behavior – not the bonuses – are responsible for the crisis.

Wall Street Journal 2010.

« Regulating Banks… », The Economist 2010 (2).

The crisis was clearly the result of excessive risk-taking from the banking and financial community despite a banking regulation constraining banks to maintain a certain level of capital based on their risk exposure. Even if most of banking systems enforced Basel I or II implicitly or explicitly before the crisis and were above the minimum required, their level of capital6 did not resist to the extent of the losses. Nonetheless it worth underlying that in the US the banks mostly exposed to the “subprimes” crisis were the investment banks given that three out of the big five disappeared one way or the other: Bear Stearns has been taken over by JP Morgan Chase in March 2008, Merrill Lynch has been bought by Bank of America and Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in September 2008.

Only Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley – the biggest ones – have been able to resist. None of these banks was concerned by the Basel Accord or any other kind of capital regulation7. Now it is true that even the two “surviving ones” are no longer investment banks since they applied to become “bank holding companies” and member of the Federal Reserve System in order to benefit “officially” from the existing safety net and to be able to offer deposit accounts as well.

The key question when it comes to the soundness of the banking sector is the following: how to avoid repeating such an excessive risk- taking behavior in the future? The answer is far from being simple given the stakes and the history of the banking sector.

First of all, it is necessary to discuss the role played by the monetary policy in the development of the crisis since it did create the condition for the excessive risk-taking behavior by maintaining since 2001 interest rates at a historically record-low level. Indeed the low level of interest rates favored the development of the “real estate bubble” even more since investors were less incline to invest in the stockmarket after the burst of the “internet bubble”. Therefore before questioning the ongoing reforms in the banking sector, it is important to remind to Ben Bernanke, head of the Federal Reserve to avoid repeating the same mistakes in the conduct of the monetary policy. This issue is actually highly relevant today in light of the decision taken by the Federal Reserve at the end of 2008 to endorse a quantitative easing monetary policy. This unconventional monetary policy has been adopted since the Federal Reserve retained that lowering interest rates was not sufficient to revive the economy and avoid a credit crunch. Besides the fact that interest rates are kept to a level close to zero – a target range between 0% and 0.25%, the quantitative easing monetary policy relies on outright transactions by the Federal Reserve of a broad range of assets in order to inject massively liquidity into the system. It is important to recall that under normal economic circumstances the Federal Reserve intervenes through open market operations mainly based on “repo” transactions, in other words buying assets with the commitment to sell it back the day after. As a result, this type of operation has a limited impact on the net creation of money consistent with the goal of any orthodox monetary policy aiming at keeping inflation low. Moreover, these operations are based exclusively on T-bills. In the quantitative easing monetary policy scheme, outright transactions concern a much broader range of assets and not only T-Bills, and for maturities exceeding overnight, up to 28 days. The most striking consequences of the massive purchase has been the rapid expansion of the Federal Reserve balance sheet that almost tripled, from $800 billions at the beginning of the crisis to $2.3 trillion today8. The assets from the “private sector” bought par the Federal Reserve are primary Assets Backed Securities (the main bulk being MBS) rated AAA. This unconventional monetary policy is assorted by the following operations:

- Access to the discount window extended to primary dealers (Primary Dealer Facility), in other words the lender of last resort facility, exclusively limited to deposit-taking institutions member of the Federal Reserve System until the crisis, opened to non-member banks after the arranged purchased of Bern and Stearns by JP Morgan Chase in March 2008.

- Direct purchase by the Federal Reserve from private investors and key market participants of assets in exchange of liquidity through the following facilities: Commercial Paper Funding Facility, Asset- Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility, Money Market Investor Funding Facility and Term Asset- Backed Securities Loan Facility. These exceptional programs have been decided after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy that affected negatively the Commercial Paper market and the Money Market Mutual Fund industry.

- Long-term purchase program by the Federal Reserve of assets in order to sustain the credit market. To that purpose the Federal Reserve announced his plan to buy up to $200 billion of debt issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, up to $1,25 trillion of MBS and $300 billion of long term government bonds.

Obviously this massive injection of liquidity raises the question about the risk of inflation and the exit strategy. To that purpose, the FED already ended the Money Market Investor Funding Facility in October 2009 and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility, Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility, Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility and Primary Dealer Credit Facility on the 1rst of February 2010. The Federal Reserve also announced that it will not longer buy the debt of Fannie Mae et Freddie Mac but will maintain the Term Auction Facility for loans backed by newly issued Commercial Mortgage Backed Securities until June 2010 and for other type of loans until March 2010. There is no question over the fact that the Federal Reserve is fully aware of the potential risk of inflation associated to that policy. However, the announcement of the progressive end of the different facilities has been judged as a prudent exit strategy, especially since banks member of the Federal Reserve System have been mostly hoarding the liquidity injected by the Fed (see appendix 2). In this respect, it is worth underlying that the Federal Reserve changed its policy in terms of reserves management, they now earned an interest rate. This may help the Federal Reserve preventing banks from lending massively their excess reserves once the economy will start growing again. Indeed once the economic growth starts again, the Federal Reserve will without doubt raise its target Fed Funds rate. Given that the interest rate earned of the reserves is indexed on the Fed Funds rate, member banks will not have a strong incentive to lend massively. At the same time, the Federal Reserve can easily carry on a reverse repos program aiming at selling back the assets previously bought in order to absorb the liquidity in excess. Besides, the recent decision taken by the Federal Reserve9 to raise the discount rate (primary credit rate) from 0,5 to 0,75% confirms the exit strategy. However, the risk mainly underestimated today related to the exit strategy, is the impact on the money and capital markets of the repeated injection of liquidity since the beginning of the crisis, in particular the direct intervention with the private investors. These “rescue” operations have certainly avoided the collapse of some markets. However it would be better if they also could avoid contributing to the creation of a new bubble like some experts underline today. Indeed, through buying assets, the Federal Reserve contributes not only to maintain their value at a level that can be retained “artificially high” preventing the markets to fully adjust but also to revive the debt market encouraging governments and private companies to issue new debt. As a matter of fact, given that banks have stopped lending, private companies have no other choice than raising funds directly in the markets, that this decision has been taken on February way banks as underwriters can generate fees keeping their profit afloat and waiting for their traditional business to revive once the economic growth starts again.

Assuming that the monetary policy is not creating the conditions for the development of another bubble, the main concern today is the needed reforms for a sound banking system in the future. The Bank for International Settlements in collaboration with the governments are working hard on those issues since as it has been previously underlined the crisis took place despite the fact that most of the banks were a priori complying with the banking regulation enforced at the time, in other words they held capital ratio above the minimum required10.

The recommended reforms currently under way count five main axes11:

- Raising the quality of Tier-one core capital, in other words rising the share of ordinary stocks in the minimum required. Until the crisis those could represent only 2% of the minimum required based on the risk-weighted

- Strengthening the risk coverage not only for trading activities and securitization consistent with the announcement made in June 2009 but also for counterparty risk arising from derivatives repos and securities financing activities. This aims at limiting the contagion effect and should give an incentive for centralizing transactions, decreasing thus the share of the over the counter transactions12.

- Introducing a leverage ratio as a supplementary measure to the minimum capital required by Basel II.

- Introducing incentives to build up capital under good economic conditions that could be used under stress times. The final aim is to reach a counter-cyclical capital requirement. In addition banks would be encouraged to integrate in the calculation of capital the provisions for expected loan losses less pro-cyclical than incurred losses currently taken into account.

- Introducing a minimum liquidity standard for internationally active banks that includes a 30-day liquidity coverage ratio requirement underpinned by a longer-term structural liquidity ratio13.

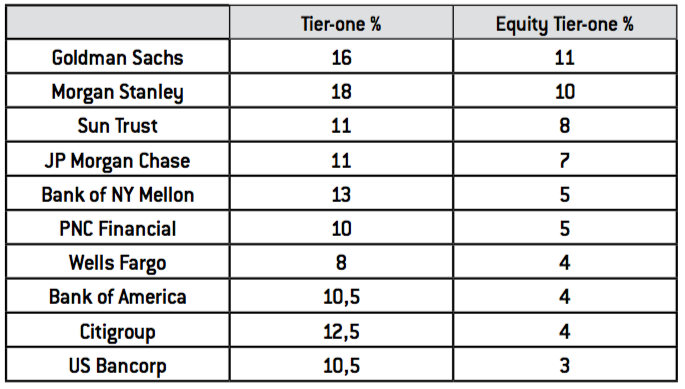

The question that needs to be answered now is the following: to what extent do these five axes taken together represent an appropriate answer to the current banking instability? Indeed the crisis confirmed a certain number of weaknesses of Basel I or II underlined by experts, in particular its pro-cyclicality. The amount of capital being calculated on the risk-weighted assets increases under economic recession worsening the economic situation and the credit rationing. The capital requirement needs to become more flexible and certain countries like Spain already experienced it with success14. Indeed the capital ratio could vary not only according to economic conditions but also according to the size of the bank and to the systemic risk that it represents. However this change does not solve the core issue: there is no capital ratio capable of resisting pessimistic scenario given the risks concentration characterizing the banks’ activity and the asymmetry of their distribution. The first axis of the reform focuses on the true capacity of what it usually defined as “capital” to absorb losses, in other words the share of the capital that absorbs unexpected losses. The crisis showed that that type of capital represented a minor share (2 to 3%) of the total capital taken into account in the Basel regulation (see appendix 3), not even half of the 8% required. Indeed, long term debt like subordinated debt included in the enlarged definition of capital in the Basel regulation, can not absorb unexpected losses by definition given that they are intrinsically debt. Certain experts would recommend a required “core capital ratio” around 8%. As a matter of fact, a recent survey of the bank of England on the last banking crises in Japan, Norway, Sweden shows that the losses tend to absorb 4,5% of the capital. These data prove that banks need to hold a risk-weighted capital ratio above the current 8% level. Nevertheless, at the same time, the crisis showed that because of the risks concentration of banks activity, defining a minimum capital requirement is very difficult task because the average level needed does not correspond to the required one under unusual stressed times. Indeed requiring a level of capital capable of absorbing losses comparable to those incurred during the crisis – up to 20% of the risk-weighted assets for some banks15 – seems not only excessive but especially costly for those banks16 and for the whole economic community. Such a level of capital would penalize the economic activity since the banks would only invest in highly profitable projects – and certainly riskier projects – in order to maintain the return expected by their shareholders. It is intrinsically unrealistic to ask to a norm such as the risk-weighted capital ratio to be efficient under any circumstances especially since the probability of having to face again a crisis as deep as the “subprimes” crisis is very low. This is the reason why new securities called “coco bond”17 (contingent convertible capital) – convertible in capital as the capital ratio is reaching a certain floor – have been issued by some banks. Nevertheless given that the crisis is the result of excessive risk taken by banks and financial institutions, it would be convenient to reflect on the measures that could curb the incentives to take risk instead of inventing new ways to face the improbable. It would be more efficient and healthy for the economy to make sure that banks are undertaking sustainable risks.

Concerning the strengthening of the required capital against trading activities and market risk in general and the adoption of leverage ratio, these measures don’t curb incentives for taking risk, it just makes that choice more costly. Indeed, the strong growth of securitization and of the Credit Default Swaps18 market revealed that incentive to take greater risk and the desire to circumvent the regulation in place. The securitization has been greatly encouraged by the regulation itself since the cost in terms of capital of holding a mortgage was higher than the same mortgage securitized and held off-balance sheet. This is not surprising if banks have consequently securitized massively mortgages in the last 5 years. To the discharge of the regulators, it is very difficult for them to predict the reaction of banks to the regulation, in particular the innovations that would help them to circumvent it19. Under these circumstances, any regulation is meant to fail if it does not take into account that fact.

As for the introduction of a leverage ratio as a supplementary measure to the required capital ratio, this is not the most appropriate answer to the core problem of the incentive to maximize it. Maximizing the leverage is consistent with the desire of banks to keep seeking more risk. It would be more urgent to understand the reasons why banks and financial institutions are ready to assume such risk exposure. This is the key for reforming adequately the system and promoting a sound banking system.

Finally regarding the introduction of new norms on liquidity, this aims at taking into account the fact that banks rely nowadays heavily on the money markets for managing their liquidity. The crisis underlined the risk of that strategy. Indeed the development of money markets changed radically the way banks were managing their liquidity, in particular they have been reducing their primary reserves (in central bank money) in favor of secondary reserves, in other words highly liquid money market instruments like T-Bills in the US. Moreover in order to face the decrease of deposits as a consequence of the development of the Money Market Mutual Fund, banks have been raising funds in the money markets exposing themselves to the changes of the market conditions in terms of amount and rate20. This new developments led some banks to increase their transformation activity: in other words the maturity gap between assets and liabilities increased. Consequently banks are more exposed to the transformation risk. Under those circumstances, it did not come as a surprise that once the crisis started and money markets dried up, banks could no longer refinance themselves. This explain why banks holding a greater share of their liabilities as deposits have been resisting better at first because they were less dependent on market conditions. In this respect, it made sense for the two ex-leading investment banks that survived the crisis – Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley – to apply for becoming bank holding company, besides the fact they have now officially the right to access the lender of last resort and they can be covered by the deposit insurance scheme, they can attract deposits as well. Nevertheless we keep coming back to the same question: whether it concerns the management of their capital position or the management of liquidity, banks have been taken more risk.

The reforms announced by the Basel Committee should be enforced by 2011-2012. At the same time, the governments in a more or less coordinated manner have come with supplementary proposition of reforms. The most recurrent one concerns the traders’ bonuses21. Nevertheless, the last plan that made tumbled the stock markets and worried the banking and financial community has been announced by the American president Barack Obama and aims at restricting banks’ size22. The project recommends to forbid member banks of the Federal Reserve System – those having access to the lender of last resort facility and which deposits are covered by the insurance scheme – from engaging their own funds in proprietary trading, and holding, investing or sponsoring hedge funds or private equity. Also there will be a strengthening of the 1994 law forbidding a bank from buying a competitor if the share of the insured deposits exceed 10% of the total market share by enlarging the definition of the resources concerned to short term resources like repo transactions. Introducing a limit to the assets held by a same bank is also discussed. This plan does not aim at revisiting the Glass-Steagall Act that separated deposit-taking institution from investment banks but at limiting the contagion effect and protect the taxpayers that in last resort pay the price for saving the system from collapsing. Anyway it would not be appropriate to separate again the two activities – even if some voices strongly defend this idea – since as the crisis showed, the banks mostly affected were the “big five” investment banks. Moreover the two surviving ones have decided since then to apply for bank holding companies and from now on have access to the discount window of the Federal Reserve. Also in Europe where the conduct of both activities represent a strategy explaining the large numbers of mergers and acquisitions that started in the 1990’s – in particular in France -, the experience pleads in favor of positive synergies between these activities. Therefore restricting banks’ size in order to limit risk taking is not an appropriate answer even if the combination of both activities offers a larger variety of products potentially “risky” to invest in. However the combination of those activities does not explain the decision to take more risk. It is understandable from President Obama to be willing to show his commitment to protect the taxpayers interest by separating activities benefiting from the government protection from those that could go bankrupt. The intention is respectable but it is also legitimate to question the credibility of the threat of letting the banking institutions going bankrupt. Indeed, during the recent crisis, while investment banks were not supposed to have access either to the lender of last resort – the Federal Reserve discount window – or to the protection of the government, they actually benefited from the government safety net except for Lehman Brothers that had only access to the discount window between March and September 2008. It is highly improbable based on what happened after Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, that the government will ever let again fail a major banking or financial institution that represents a systemic risk. To conclude on proprietary trading, one point seems to be undermined by the authorities: when banks engage their own funds together with those of their clients in hedge funds or private equity, it is a signal of quality for the final investor and a mean for the bank to have a better access to inside information and control over the invest- ment strategy of the fund. Finally, proprietary trading does not represent an important stake – between 1 and 5% of the income of the major US banks except for Goldman Sachs for which the percentage reaches almost 10%23. Anyway, restricting banks size does not curb risk taking.

What reforms for curbing risk taking behavior?

Although the insurance of deposits had led to certain excesses, depositors being no longer concerned by monitoring their banks, the degree of opacity of the banking activity does not always allow the premium paid to reflect the “true” risk faced by the banks.

The “too big to fail” policy is an explicit strategy endorsed by the US banking and monetary authorities even if many other developed countries implicitly follow it as well.

Alessandri-Haldane 2009, p. 3, 23.

Ibid., p. 16, 29. In 1998, the five biggest banks at the international level held 8% of the total banks’ assets meanwhile in 2008 they held 16%.

Calomiris 1997, 2008.

To find out more about the history of clearinghouses in USA, see Timberlake.

Except for Charles Goodhart 2008 et Alessandri-Haldane 2009, p. 13-14.

See in particular Berle-Means 1968 et Wirtz 2008.

Alessandri-Haldane 2009, p. 14, Grossman 2001, 2006 et 2007, and Wilson-Kane 1996.

Grossman 2001, 2006 et 2007, and Wilson-Kane 1996.

Grossman, 2001.

Ibid.

Alessandri-Haldane 2009, p. 3.

It may explain why it resisted better to the crisis.

Alessandri-Haldane 2009, p. 17.

Goodhart 2008 and Alessandri-Haldane 2009.

Under a regime of unlimited liability as in the case of partnerships, shareholders are all liable on their personal wealth and for this reason shareholding can look like a very private “club”.

The origin of the crisis has been clearly identified: the crisis resulted from an excessive risk taking coming from the whole banking and financial sector – banks, financial institutions, brokers… It is now crucial to understand the reasons for that behavior. The banking sector is key to the financing of the economic activity and for that reason has benefited since almost a century of implicit and explicit guarantee schemes from the State. Explicit guarantee schemes usually include access to the lender of last resort and deposits insurance. Those schemes do not necessarily encourage risk-taking behavior if the price paid corresponds to the banks’ risk exposure24. Incentive for risk taking becomes an issue when the guarantee scheme covering the banking sector is implicit like the “too big to fail” policy in the US25. This policy relies on the idea that because some banks or financial institutions represent a systemic risk they need to be saved at any cost. Looking at the past banking and financial crises since the 1930’s, it is worth underlying the fact that there is a systematic intervention of both the State and the monetary authorities to limit the banks’ losses at the expense of taxpayers. During the last crisis, the total financial support offered by Great Britain, the USA and the States of the Euro zone to their banking system reached a record-high of $14 trillion or 25% of the total GDP according to a survey published by the Bank of England26. It is legitimate for those banks and financial institutions to feel secured and not concerned by the risk of going bankrupt. Under those circumstances, the activity of control that is supposed to be exercised by private investors reflected in the risk premium is not performed efficiently. Indeed the market discipline does work efficiently if and only if private investors incur losses in case their investments fail. Now this is not what the history of the recent banking crises shows and the future does not look brighter given that the last crisis increased further the banking concentration – it doubled in the last 10 years27, a strong sign in favor of maintaining the “too big to fail” policy. It is highly doubtful to expect market discipline to curb efficiently excessive risk taking behavior. Therefore it would be hazardous to rely on it as a tool for regulating the banking and financial industry as defended since many years by C.W. Calomiris28: as long as the “too big to fail” policy exists, private investors will keep underestimating their risk exposure. Nonetheless giving up on that policy is far from being an easy decision to take in particular after the devastating consequences of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy even if the decision of the Federal Reserve was fully justified in this case. As a matter of fact, investment banks are not supposed to be protected by the monetary authorities safety net but in March 2008 after the Bear and Stearns debacle, the Federal Reserve decided to grant them exceptionally the access to the discount window. Therefore Lehman Brothers had had 6 months to solve their liquidity problems but in spite of that their situation worsened. Under these circumstances, its bankruptcy seemed inevitable especially since it was time to signal to the markets that there were limits to the “too big to fail” principle. Nevertheless today it is very doubtful that the US monetary authorities would have taken the same decision. If the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy was to set an example, it failed! Therefore it is legitimate to be concerned by the next crisis given that the implicit guarantee covering the banking sector has never been so limitless. For the record during the last crisis the Federal Reserve and the US government “rescued” not only commercial banks but also two government sponsored agencies – Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – and the insurance company AIG.

The “too big to fail” policy remains a key issue and needs to be adequately debated if the ultimate goal of the reforms currently discussed is to promote a sound banking and financial system. The regulators have 2 options: or they fully endorse the “too big to fail” policy and they need to take into account their negative externalities in the design of the reformed regulation in order to avoid as much as possible the insidious side effects denounced previously and put in light by the recent crisis; or they give up this policy but they need to find a credible way to do it and in the after-crisis environment this aim is far from being easy to achieve. As underlined earlier, the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy that was meant to set an example signaling a change in the “too big to fail” policy, just comforted that policy since it is quite obvious that the monetary authorities regret the devastating consequences that decision had on the markets. If the “too big to fail” policy is maintained in the future – what is most likely the case – it would be useless to separate again the com- mercial banks from the investment banks, revisiting to some extent the Glass Steagall Act. Indeed, as it has been underlined many times, during the last crisis, investment banks were not supposed to have access to the Federal Reserve discount window but they did starting in March 2008 as an extension of the “too big to fail” policy. Under these circumstances, the decision to separate again commercial from investment banks would be difficult to defend as a credible solution that would guarantee a perfect separation between activities. On the contrary, the recent trends that have been affecting the banking business showing an increased interdependence between banking activities and financial markets, the last decisions taken by the monetary and banking authorities and the major bank concentration tend to invalidate such a idea.

As regarding the pure abandonment of the “too big to fail” policy, its implementation is highly compromised given the past record unless there is a total revision of the missions assigned to the central bank. Indeed, it would require from the central bank to restrict its action to the monetary policy and give up on the lender of last resort function. Performing the two functions under the same roof introduces some confusion in the definition of the exact perimeter of its action. Without denying the advantages of having a lender of last resort, it would be worth revisiting the history of the private clearinghouses that existed in the USA before the creation of the Federal Reserve System. Indeed privatizing the lender of last resort function presents many advantages: the private clearinghouses are managed by their members, in other words the commercial banks set their own rules for admission but the rules defining the access to liquidity facility available in case of temporary illiquidity as well29.

Given the main job of clearinghouses, they can easily step into solving temporary illiquidity problem that concerns an individual bank or the whole members. In the case illiquidity affects all the members of the clearinghouse – situation a lender of last resort tries to prevent and if necessary, solves – the clearinghouse can issue a higher form of money based of the reserves held by the members which circulation is restricted among members and cease to exist as soon as the crisis is over. There are many advantages in privatizing that function: commercial banks members of the clearinghouse are more equipped to assess correctly the financial state of their peers and to price adequately the penalty in case of temporary illiquidity of a single bank. Moreover given that clearinghouses don’t hold the monopoly to issue currency, their capacity to finance their members in case of illiquidity problems is limited. This is a credible way to end the “too big to fail” policy. Nevertheless privatizing the lender of last resort just solve partially the problem of the “too big to fail” policy. As a matter of fact this does not prevent the government from being willing to rescue their “big banks”. The solution to limit that risk would be to write in the Constitution that government is prohibited to rescue banks or financial institutions.

Besides rethinking governance rules currently at work in the banking organizations could be a way to limit excessive risk taking behavior but this idea is rarely discussed30. Indeed under the current system, banks are mainly incorporated under limited liability. In other words, in case of bankruptcy, shareholders only loose their shares. If they optimize the diversification of their portfolio, their exposure to losses can be extremely limited. Under these circumstances, there is low incentive to control the decisions taken by managers. These issues are not new in the field of corporate governance literature related to the separation of ownership and control and have been heavily debated since the 1930’s31. Under limited liability, decisions taken by managers are mainly controlled by external creditors if stockholders have a limited incentive to monitor given their low stake in the company. Now both explicit and implicit guarantee schemes offered by the monetary and banking authorities and the government, have never been so extended. Therefore this situation explains why creditors may systematically underestimate risk in the banking industry and underprice it as a result. This is the reason why, as it has been mentioned earlier, the market discipline can not work efficiently. It seems like the current situation is unprecedented: banks and financial institutions can take risky decisions with complete impunity given that there is no longer any mechanism of control at work. Shareholders like creditors know they will be protected by the monetary and banking authorities and the government even if some actors of this game loose like the CEO’s of “rescued” banks.

In front of such dead end, it is worth reminding that limited liability has not always been a standard in the banking industry and even less in the financial industry in the USA as in Europe. Indeed, in Europe like in the USA, limited liability became a standard not before the XIX century32. In the USA, the double liability of commercial banks’ shareholders33 prevailed in some states until the crisis of the 1930’s. The “double liability” means that shareholders could loose up to twice the amount of their investment. This regime of “extended liability” had been adopted by the most economically developed American states meanwhile the less developed ones adopted limited liability34. This desire of changing regime as standard of living increases shows the major weakness of the limited liability case, in other works the incentive to take risk. At early stages of economic development, incentive to take risk may be encouraged as it “accelerates” economic growth. As soon as a certain level of economic development is reached, it is convenient to slow it down. Grossman in his article35 shows the benefits of taking risk – the creation of wealth – exceeds the costs – the losses incurred in case of default – until a certain level of economic development is reached. After it is worth curbing risk-taking behavior in order to protect the living standard of the country. This explains why the more economically developed states of the east cost of the US adopted the “extended “liability regime until the crisis of the 1930’s. At that time the banking and financial sector did not enjoy any protection or guarantee scheme from the monetary authorities and the government. On the contrary, as underlined in Alessandri and Haldane article36, the governments were heavily dependent on the banks and financial institutions as they were the major holders of their debt. It is worth underlying the fact that economic agents aware of the potential weaknesses of the limited liability regime decided to adopt the “extended” liability regime in order to control for risk. In this respect, it is important to remind that investment banks were until recently incorporated as partnerships in other words under unlimited liability, the last investment bank that applied for limited liability being Goldman Sachs37. The same is true for the so blamed hedge funds industry that regroup numerous small size companies all incorporated as unlimited liability corporations knowing that this activity has developed outside of any regulation and is not covered by any safety net or guarantee scheme38. It seems that the regime of “extended liability” is a way to give some insurance to creditors as to risk taking behavior and helps building reputation in the banking and financial activities characterized by a high level of opacity. Indeed under a limited liability regime, the risk control activity falls mainly on creditors. This is not an optimal outcome when risks concern opaque and sophisticated activities. Even if banking and financial activities were no longer implicitly and explicitly protected, it is highly doubtful that creditors will be capable to assess adequately the risks because of the degree of sophistication of the financial products conceived by engineers. The proof – if needed -, is the collapse of the Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDOs) market as soon as investors holding equity tranches understood that the cumulated default of payment on the “subprimes” mortgages would affect them but were unable at the same time to measure accurately the extent of the losses. This episode indicates clearly that investors from systematically “underestimating” the risk, started to “overestimate” it systematically: this situation let to a total incapacity of valuing products. These extreme behaviors observed and the high volatility characterizing the markets were showing the limits of the investors ability to understand the underlying mechanisms of products’ valuation.

In this context, it is urgently needed to revisit the question of the “extended” liability regime even if when the idea is debated – in other words very rarely – it is rapidly disregarded39. Nevertheless it appears that unlimited liability is spontaneously adopted by economic activities where reputation is a sign of the quality of the services offered. This regime has been adopted as a start by many commercial banks, invest- ment banks, insurance companies, auditing companies…many activities where information is opaque, difficult to read and understandable by outsiders even if they are so-called “informed”. Under these circumstances, unlimited liability can be perceived as a commitment taken by shareholders to control efficiently the risk taken by the managers given that they can loose part or their entire wealth in case of bankruptcy. Unlimited liability acts like a guarantee of reputation. Nevertheless adopting that regime raises the question of the nature of shareholding. Indeed, the liability of shareholders going behind their investment, it is understandable that the incumbent shareholders are willing to screen the potential new comers. It is important to determine if the applicants possess enough wealth to absorb the losses in case of problems. The access to shareholding is therefore less democratic40 than under limited liability where this concern does not exist. As a consequence, rising funds is less easy and more expensive and this may slow down the growth of banks’ business and by the same token the rate of economic growth. It is always possible to open more widely sharehoding under unlimited liability in order to facilitate fundraising but this strategy can be disastrous for those shareholders which wealth is comparatively low. Indeed this is what happened to the shareholders of the English insurance company Lloyd’s. During the years 1970’s and 1980’s the insurance company decided to open its shareholding (the famous “names”) to “less wealthy” shareholders but those late comers went bankrupt when the company faced heavy losses at the end of the 1980’s41. Nevertheless it is worth underlying that part of the activity of the insurance company – the part concerning natural disasters is characterized by radical uncertainty that makes risk unpredictable and impossible to master efficiently: by definition, it is impossible to predict an accumulation of natural disasters. This is partly due to such an accumulation that Lloyd’s went almost bankrupt. To that regard, the risk faced by banks is less unpredictable even if its predictability can result from a complex valuation process. Therefore, the probability a bank may experience the same situation is low.

Nevertheless it is important to remind that “extended” liability is not “crisis-proof” and does not intend to be. As a matter of fact, this regime still prevailed in some States when the financial crisis of the 1930’s outbursted and in this respect it did not prevent it to occur42.

However the reason why the question of “extended liability” should not be disregarded is related to the fact that it can solve the problem raised by the increasing opacity of banking activities that undermine considerably the ability of creditors to control risk efficiently. Now it is important to keep in mind that under limited liability those who are effectively in charge of controlling risks are the creditors through the risk premium they ask given that they are the ones mainly exposed to losses in case of bankruptcy. Today the degree of sophistication of innovative financial products represents a major obstacle to an efficient external control of risks, that control being exercised by “informed” investors or by regulators. This fact needs to be taken into account in any reflection led on the reform of the banking system. The banking authorities – Basel Committee included – don’t have much to offer to solve this problem given that regulation generates itself financial product innovation meant to circumvent it which impact can not, by definition, be taken into account making regulation inefficient, if not counter-productive. In this context, the solution can only come from internal control for risks and in order to maximize its efficiency it needs the stakeholders to be highly exposed to the risk of bankruptcy: this is the case under a regime of “extended” liability and even more under unlimited liability. However the required condition – if that regime was to be adopted – would be to give up first on the “too big to fail” policy. Indeed, if the “extended” liability exists in an environment where shareholders are not sanctioned in situation of major losses, then the control of risks by shareholders can not be optimal. Thus the implementation of such a radical reform would require not only the change of banks’ regime from limited liability to “extended” liability but also the decision to end the “too big to fail” policy, or by privatizing the lender of last resort function, or by writing in the Constitution the prohibition of the government to rescue the ban- king and financial sector as suggested earlier. If the abandonment of the “too big to fail” policy seems quite unlikely – but not impossible, it is a question of political will – on the other hand adopting the “extended liability” regime could result from discussions led by banks within their association. This would give a strong signal that would prove to the public that banks have learned their lesson and fully assume their responsibility in the extent of the crisis and are committed to reform in depth the system.

This study put in light “the Graal” after which the national and inter- national banking authorities together with the governments are going. Indeed the recommended reforms currently adopted in order to face the crisis in many countries and in particular in the USA, just comfort the idea that the banking and financial sector is a sector apart that can not be ruled by market discipline and especially can not fail. This strong belief confirms definitely that the “too big to fail” policy will continue to prevail for a long time and this makes impossible any attempt to reform the system in depth as it has been demonstrated previously. Giving up on the “too big to fail” policy is certainly a very difficult decision to take in light of the Lehman Brothers episode in September 2008 and it is perfectly understandable that the authorities may be reluctant to make that decision. However any attempt to fully reshape the system under the current conditions seems useless since the existence of the “too big to fail” policy prevents any mechanism of external risk control to work efficiently. Moreover, the sophistication of the banking activities stimulated by the very existence of regulation is an obstacle to an efficient external control of risks, that external control being exercised by private investors or by regulators.

As a result, the reshape of the system in order to reach the ultimate goal of delivering stability require as prerequisite the abandonment of the “too big to fail” policy. However, the credibility of such intention is largely questionned in the after-crisis context. Under those circumstances, the banking and monetary authorities in collaboration with governments are left with few alternatives as discussed previously if they want to prove their commitment to achieving banking soundness. They need to take radical decisions like privatizing the lender of last resort function and prohibiting governments to assist financially the banking and financial institutions in the Constitution. Moreover the activity of risk control needs to be “reinternalized” in order to be optimized; in other words, risks need to be monitored internally by shareholders. Those latter would have an incentive to perform that function only if they are exposed to heavy losses in case of bankruptcy. This is the reason why changing the banking and financial institutions’ regime in favor of “extended” liability could have the virtue to send a strong signal to the market showing the desire to take risk under control for good.

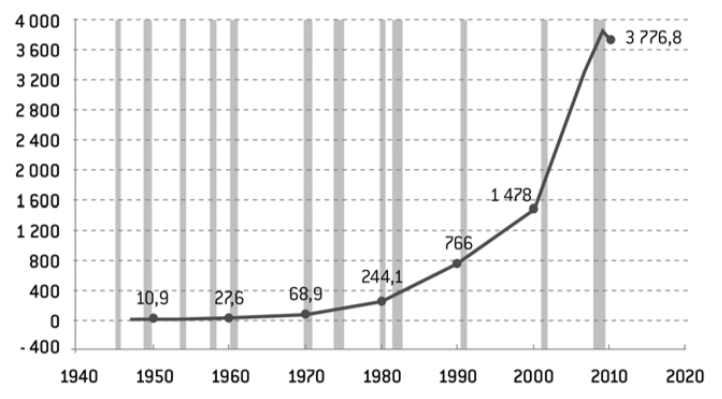

Chart 1 : real estate loans at all commercial banks (REALLN) (billions of dollars).

Copyright :

Shaded areas indicate u.s. recessions

Source :

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis Economic Data FRED, 2010.

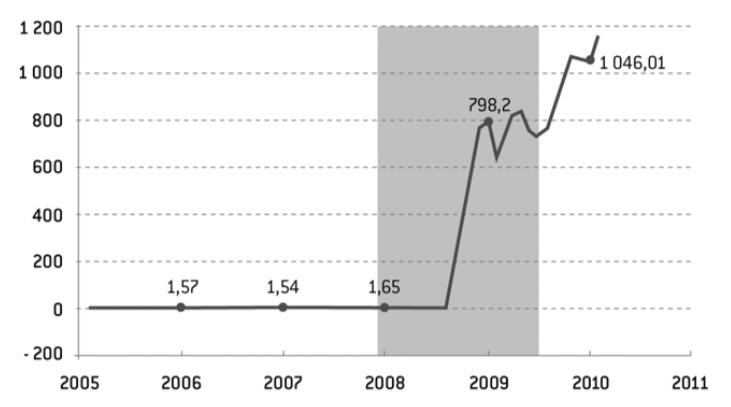

Chart 2 : excess reserves of depositary institutions (billions of dollars).

Source :

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis Economic Data FRED, 2010.

Table 1: ratios calculated by The Economist

Source :

The Economist, February 2009.

« Reforming banking Camp Basel » and « Reforming banks: The Weakest Links », The Economist, 21 janvier 2010.

« Regulating banks: garrottes and sticks » and « Buttonwood: Not What they Meant. The unintended consequences of past financial reforms », The Economist, 28 janvier 2010.

Wall Street Journal, 22 janvier 2010.

Alessandri (P.) and Haldane (A.G.), Banking of the State, Bank of England Publications, novembre 2009.

Bank for International Settlements, Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management and Supervision, septembre 2008.

Bank for International Settlements, Strengthening the Resilience of the Banking Sector, décembre 2009.

Berle (A.A.) and Means (G.C.), The Modern Corporation & Private Property, Harcourt, Brace & World, New York, 1968 (1932).

Blundell-Wignall (A.), « Structured products: implications for financial markets », Financial Market Trends, n°93, OCDE, novembre 2007, p. 1-31.

Calomiris (C.W.), The Postmodern Bank Safety Net, AEI Press, Washington, D.C, 1997.

Calomiris (C.W.), « The subprime turmoil: what’s old, what’s new, what’s next? », Symposium on Maintaining stability in a changing financial system, Federal Reserve of Kansas City, 21-22 août 2008, p. 1-113.

Commission bancaire, « Le système bancaire et financier français en 2008 », Rapport annuel de la Commission bancaire, 2009, p. 1-85.

Cousseran (O.) et Rahmouni (I.), « The CDO market: functioning and implications in terms of financial stability », Financial Stability Review, no 6, Banque de France, juin 2005, p. 1-20.

Delanglade (S.), « Les naufragés du Loyd’s », L’Express, 8 juin 1995.

Goodhart (C.A.E.), « The regulatory response to the financial crisis », CESifo Working Paper, no 2257, mars 2008, p. 1-25.

Gorton (G.), 2008, « The panic of 2007 », Symposium on Maintaining Stability in a Changing Financial System, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole Conference, août 2008, (rév. octobre 2008), p. 12-17.

Grossman (R.S.), « Double liability and bank risk taking », Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 33, no 2, 2001, part. 1, p.143 -159.

Grossman (R.S.), « Other people’s money: the evolution of bank capital in the industrialized world », Wesleyan Economics Working Papers, n°2006-020, University of Weysleyan, Middletown, avril 2006, p. 1-27.

Grossman (R.S.), « Fear and greed: the evolution of double-liability in American banking, 1865-1930 », Exploration in Economic History, n°44, 2007, p. 59-80.

Heider (F.) and Hoerova (M.), « Interbank lending, credit risk premia and collateral », Working Paper Series, Banque centrale européenne, n°1.109, novembre 2009, p. 1-46.

Timberlake (R.H.), « The central banking role of clearinghouse associations », Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 16, n°1, février 1984.

Wilson (B.K.) and Kane (E.J.), « The demise of double liability as an optimal contract for large-bank stockholders », NBER Working Paper Series, n°5.848, décembre 1996, p. 1-31.

Wirtz (P.), Les meilleures pratiques de gouvernance d’entreprise, Paris, La Découverte, coll. « Repères », 2008.

No comments.