Introduction

The Afghan flight to Europe

Secondary movements

France, a country of asylum for afghans

The challenge of employability

A significant public order issue

Afghan women made invisible

Conclusion

Summary

In the wake of the Syrian crisis, the closure of Northern European borders and the collapse of the Afghan regime, France has become one of the main countries hosting Afghan refugees since 2015. With more than 100,000 Afghans present in 2024, this migration has become a massive phenomenon, recent and unexpected in its scale.

This movement is made possible by France’s relatively protective asylum system. In 2024, more than 70% of Afghans who applied for asylum were granted international protection (refugee or subsidiary protection), compared to less than 40% in some European countries. These differences in recognition encourage ’secondary movements’: people who have been rejected in other European Union countries come to seek asylum in France.

This dynamic reveals many weaknesses: the majority of Afghans arriving are young, male, poorly educated, and often struggle with language learning and professional integration. The social conservatism in Afghanistan, which migrants retain to some extent, is difficult to reconcile with French values, particularly on issues of freedom of conscience and women’s rights. This contrast is especially visible in the virtual absence of women among this migrant population: they represent less than 20% of exiles, reflecting their marginalisation in Afghan public life.

Afghan migration is thus putting the French model of integration to the test. It highlights the gap between the values of the Republic and the cultural realities of Afghan refugees, while also highlighting the limits of reception capacities, which are now saturated and difficult to reconcile with a so-called ‘open’ migration policy.

Didier Leschi,

Executive director of the Office français de l'immigration et de l'intégration (OFII)

He is the author of the book Ce grand dérangement. L’immigration en face [This great upheaval. Focus on immigration] (Gallimard, coll. “Tracts”, 2020) and of the

study Migrations : la France singulière [Migration: France’s unique position] (Fondation pour l’innovation politique, October 2018).

Swedes and Immigration : End of homogeneity? (1)

Swedes and Immigration : End of the consensus ? (2)

“Sweden Democrats" : an anti-immigration vote

Danish Immigration Policy: A Consensual Closing of Borders

Unity in Diversity: a portrait of Europe's Muslims

A diverse community: a portrait of France's Muslims

An integrated mosque for a spiritual and progressive islam

Islamist terrorist attacks in the world 1979-2024

Islamist Terrorist Attacks in the World 1979-2021

Islamist terrorist attacks in the world 1979-2019

Values of Islam: A series of studies from the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

The inevitable conflict between islamism and progressivism in the west

Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Maghreb: the impact of Islam on social and political evolution

Are Europeans abandoned to populism?

Source :

“Afghan Displacement Summary Migration to Europe”, Danish Refugee Council, november 2017

In 1978, the clandestine Communist Party staged a coup with the support of Afghan officers trained in the USSR. Although successful, the new Government quickly faced strong popular resistance, prompting the Soviet army to intervene on a massive scale.

“US Costs to date for the war in Afghanistan 2001-2021”, Costs of War Project Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University, April 2021 [online].

Afghanistan has experienced violence, war and political turmoil for forty years. This situation explains why Afghans are among the largest refugee populations in the world. Between the communist coup in 19781 and the Russian withdrawal in 1992, Afghans, engaged in a strategy of survival, represented the largest wave of migration since the Second World War. The Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in August 2021 has once again forced hundreds of thousands of Afghans onto the roads. This includes those who benefited from years of Western presence: the middle class, people who collaborated with Western forces and NGOs, and women, unfortunately in too small numbers. The US withdrawal confirmed the failure of a policy that succeeded neither in defeating the Taliban militarily nor in bringing about economic, political and human development in Afghanistan. The main explanation for this failure was the choice of a strategy based more on the use of force than on support for development. Even though the Americans alone spent more than $2 trillion over their 20 years of presence, half of which went to military budgets,2 this strategy did not pay off. In comparison, the Marshall Plan, designed to help European countries rebuild their economies between 1947 and 1951, cost the United States $150 billion (in today’s prices), less than 7% of the cost paid by the Americans for the war in Afghanistan.

‘10.9 million Afghans remain displaced, almost all within Afghanistan or in neighbouring countries. In 2023, the number of Afghan refugees increased by 741,400 to reach 6.4 million, reflecting new estimates from the Islamic Republic of Iran and Pakistan.’3 First they went to neighbouring countries such as Pakistan, Iran and Turkey, and then, to North America and Europe. For a long time, Iran and Pakistan took in 85% of Afghan refugees.

Iran still had 3,752,000 Afghan refugees on its territory in 2023, and Pakistan had 1,987,700.4 However, in Pakistan, Afghan refugees are assigned to certain parts of the country and specific jobs, and are denied access to education. In Iran, more than 2 million Afghans are in an irregular situation because their visa, residence permit or even their refugee card has expired.5 Everything is being done to restrict the Afghan presence on those territories.

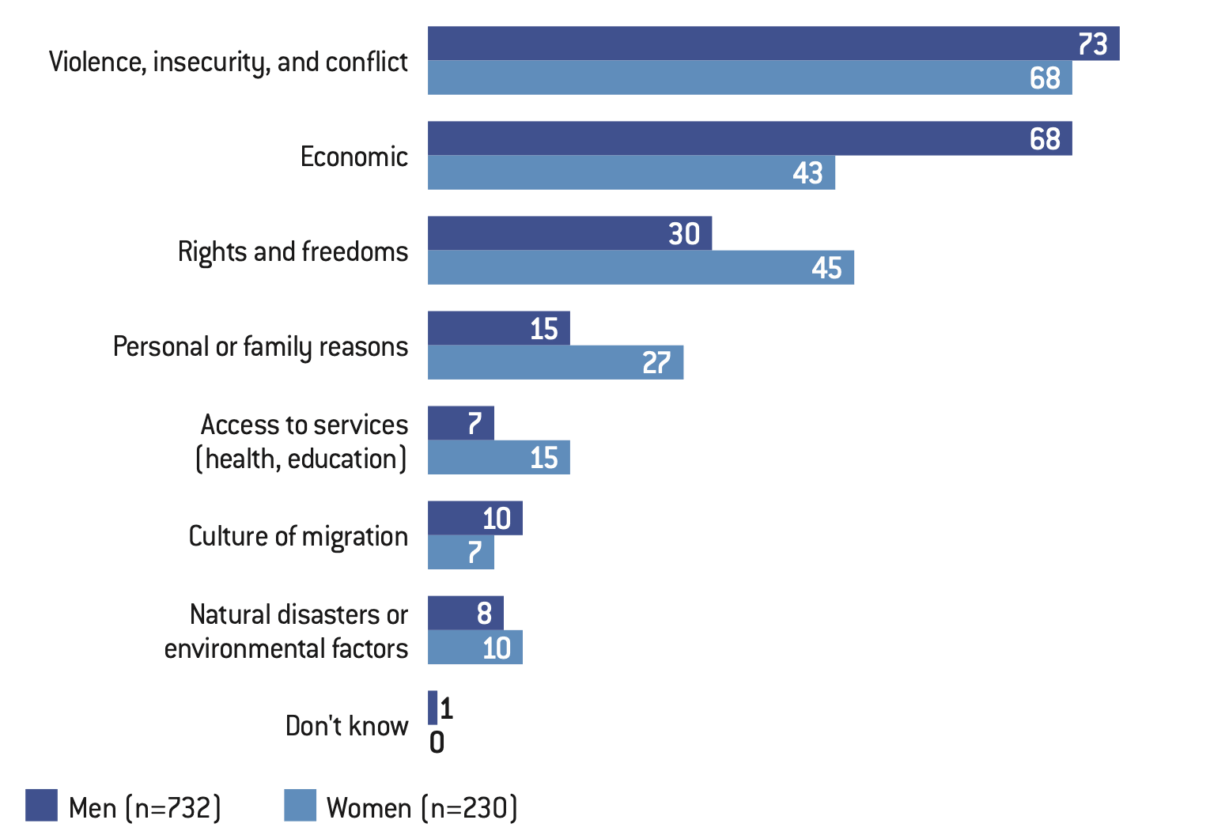

Figure 1 – For what reasons did you leave Afghanistan ?

Source :

‘Afghans in Pakistan: drivers, risks and access to assistance’, Mixed Migration Center, December 2024, fig. 1, p. 3. [online].

More than 250,000 Afghans have been deported from Iran and Pakistan to Kabul since 2021. See “UNHCR calls for help for Afghan refugees forced to leave Pakistan and Iran”, UN News, 29 April 2025 [online]. And Turkey has deported nearly 45,000 to Afghanistan. See “Turkey is turning back Afghans at its border with Iran”, Human Rights Watch, 18 October 2022 [online].

Afghan refugees face similar conditions in Turkey, where there are about 300,000. Since the fall of Kabul, the Turkish government has been deporting thousands of refugees to Afghanistan on repatriation flights. All these repatriation policies have accelerated since 20216 and have precipitated a growing number of Afghans towards Europe. In this context, Europe appears to be the place to go to enjoy better living conditions. This is all the more true given that 20 years of active Western presence in the aftermath of 9/11 have created ties that have, in turn, encouraged Afghans to come to Europe in particular.

Afghan migration has also been driven by economic hardship that the influx of dollars has failed to alleviate due to high levels of corruption among the Afghan elite, protected by NATO, and local civil servants. Today, Afghanistan’s GDP per capita remains one of the lowest in the world. It is a hundred times lower than the European average.7

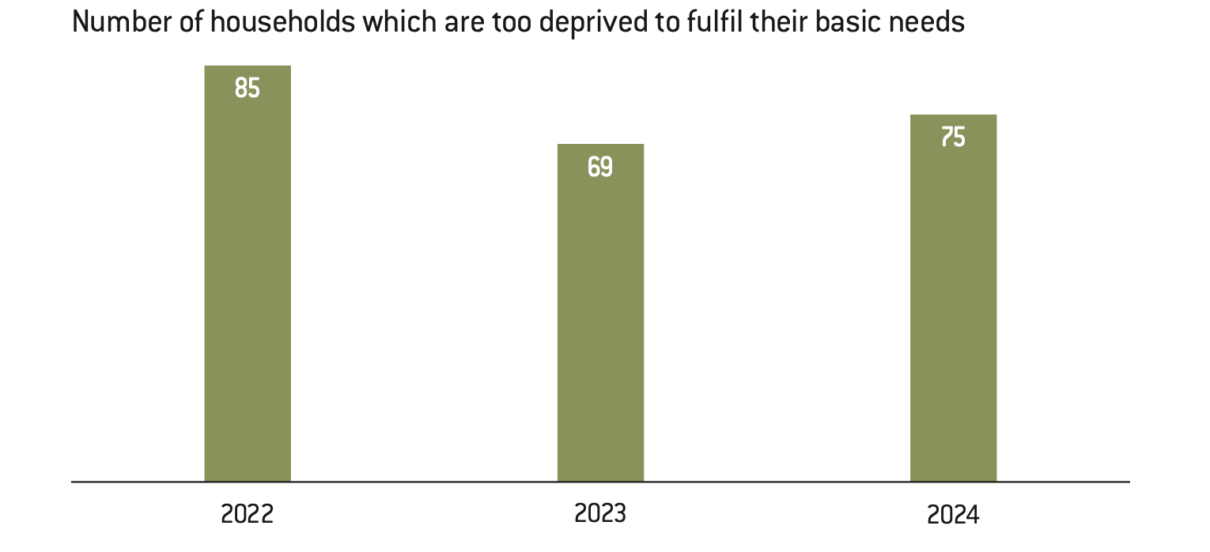

Figure 2 – Subsistence Insecurity Index

Source :

‘Afghanistan Socio-Economic Review’, UN Development Programme, April 2025, fig. 14, p. 22. [online].

Note: The subsistence Security Index was coined by the United Nations Development Programme to fill the gap in statistics on poverty in Afghanistan. This poll surveys Afghan households on 16 elements of their daily life (food, healthcare, accommodation…). Their answers give rough estimates of poverty in Afghanistan.

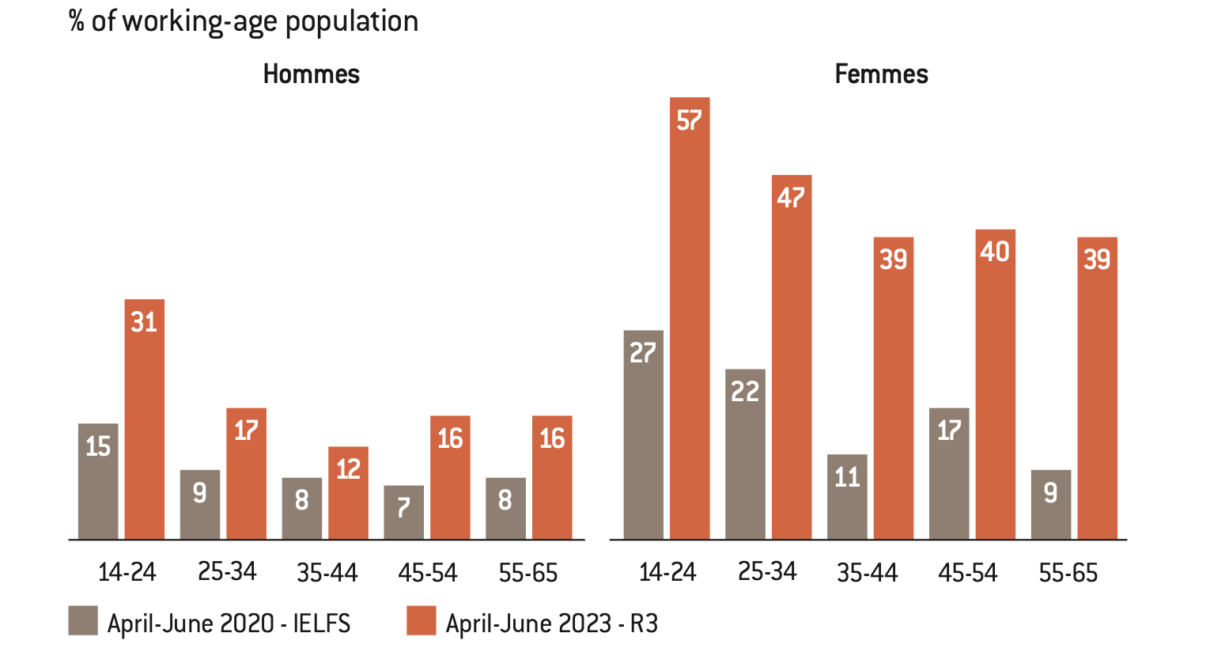

Figure 3 – Unemployment rate (age 15-65), by age and gender

Source :

‘Afghanistan Welfare Monitoring Survey (AWMS)’, World Bank, October 2023, fig. 8, p. 13. [online].

Note: Due to strong seasonal variations in employment, the estimates from the IELFS 2019-2020 were calculated over the months corresponding to the fieldwork of phase R3.

IELFS = Integrated Economic and Labor Force Survey

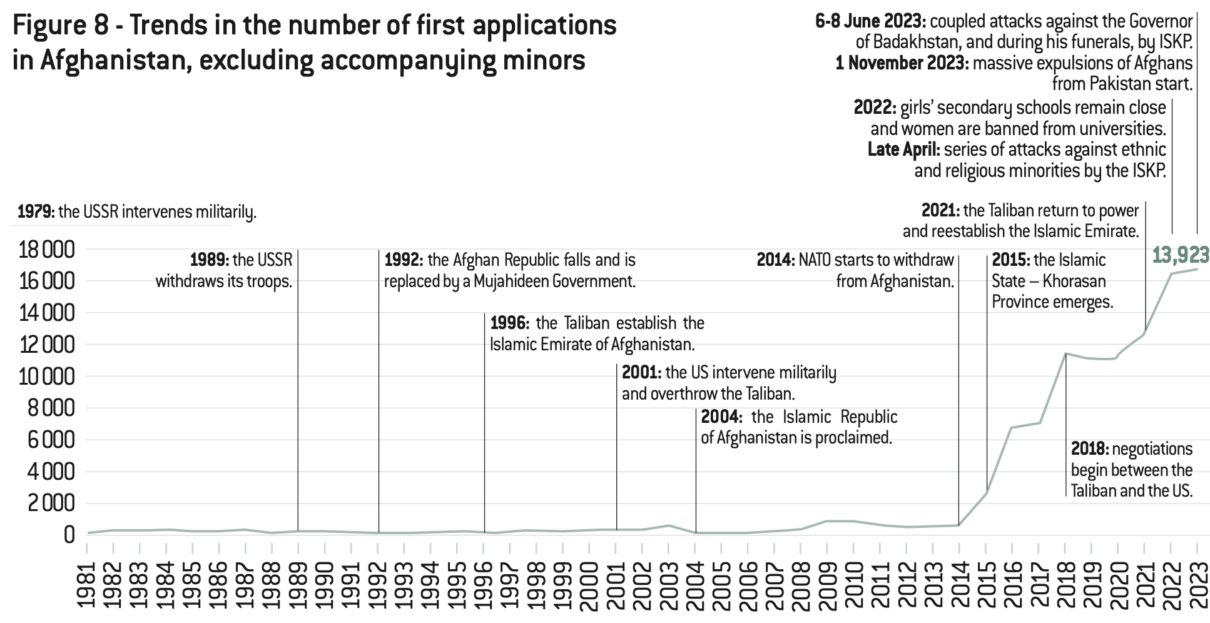

The Afghan flight to Europe

2015 was a pivotal moment in the history of Afghan migration to Europe. That year, the European Union issued 2.6 million new residence permits, including many for Afghans. For a population of 320 million Europeans, the number of new residence permits issued was proportionally much higher than that of the United States, considered a major immigration country, with 1 million new permits issued in 2015 for 340 million inhabitants.

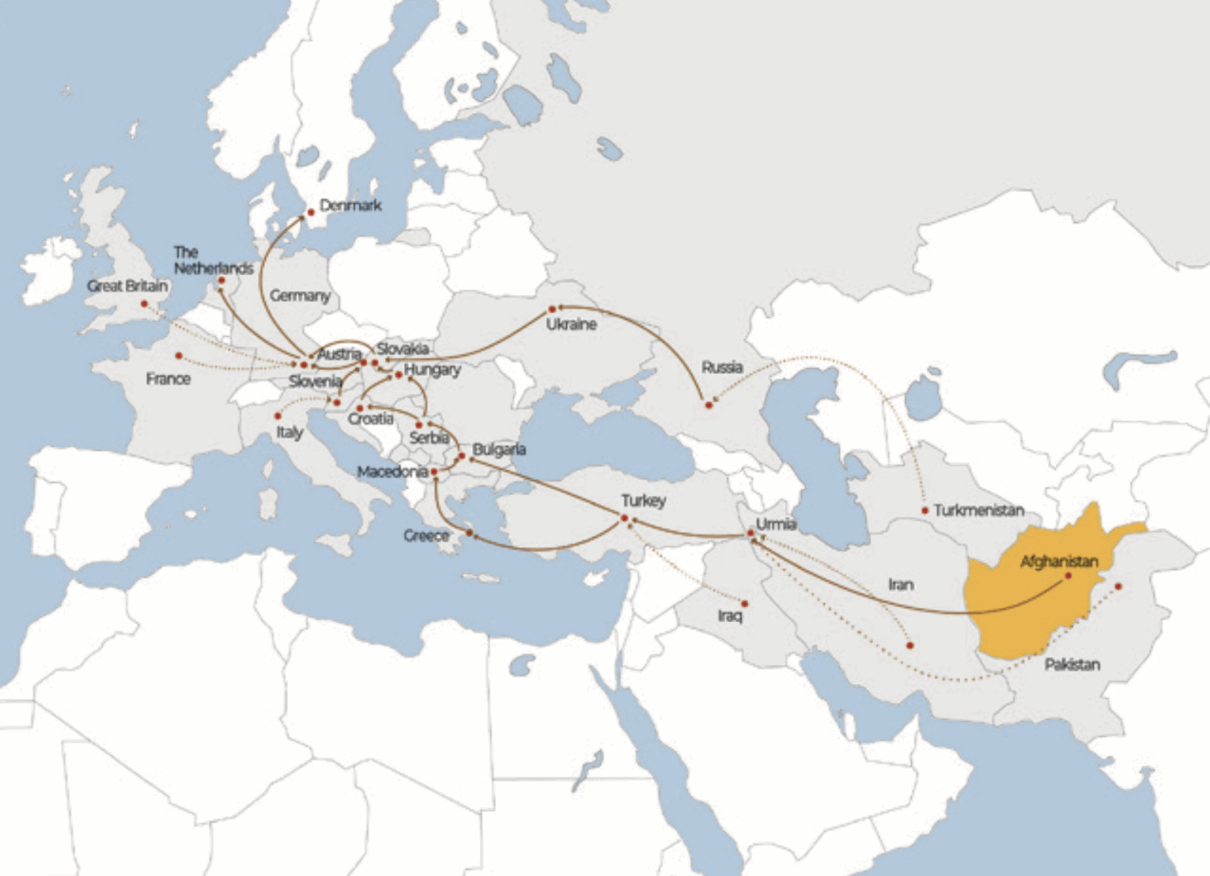

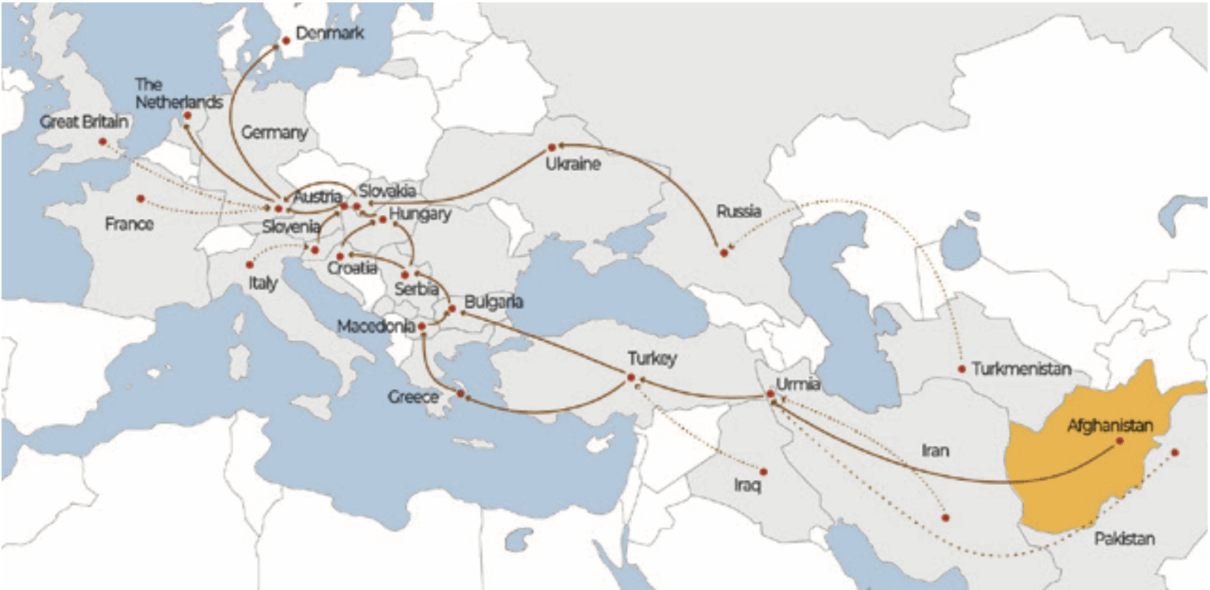

Since 2015, Afghan immigration to the European Union has both intensified and taken new routes. This reconfiguration led to the emergence of an access corridor to the European Union through Serbia. It was used by several hundred thousand asylum seekers, mainly from the Middle East and South Asia. Afghans flocked there, particularly those who saw Germany and the Scandinavian countries as a kind of ‘Holy Grail’.8

Figure 4 – Afghan immigration routes towards Europe

Source :

‘Afghan Displacement Summary Migration to Europe’, Danish Refugee Council, November 2017, pp. 5-6. [online].

In absolute terms, the number of asylum applications from Afghans within the European Union has increased fivefold. From around 42,000 applications in 2014 to 2015, it rose to approximately 195,000 in 2015. It fell slightly in 2016, before dropping sharply in 2017. Those data suggest a strong correlation between the German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s initiative to suspend the Schengen Agreement in 2015, thus opening her country’s borders to all those who wished to settle there, and the sharp increase in immigration from the Middle East, and Afghanistan in particular. At that time, the acceleration of Afghan arrivals in Europe was not linked to developments or changes in the situation in Afghanistan, although the continuing civil war, the start of the withdrawal of US forces and the intensification of Islamic State in Khorasan’s attacks may partly explain it.

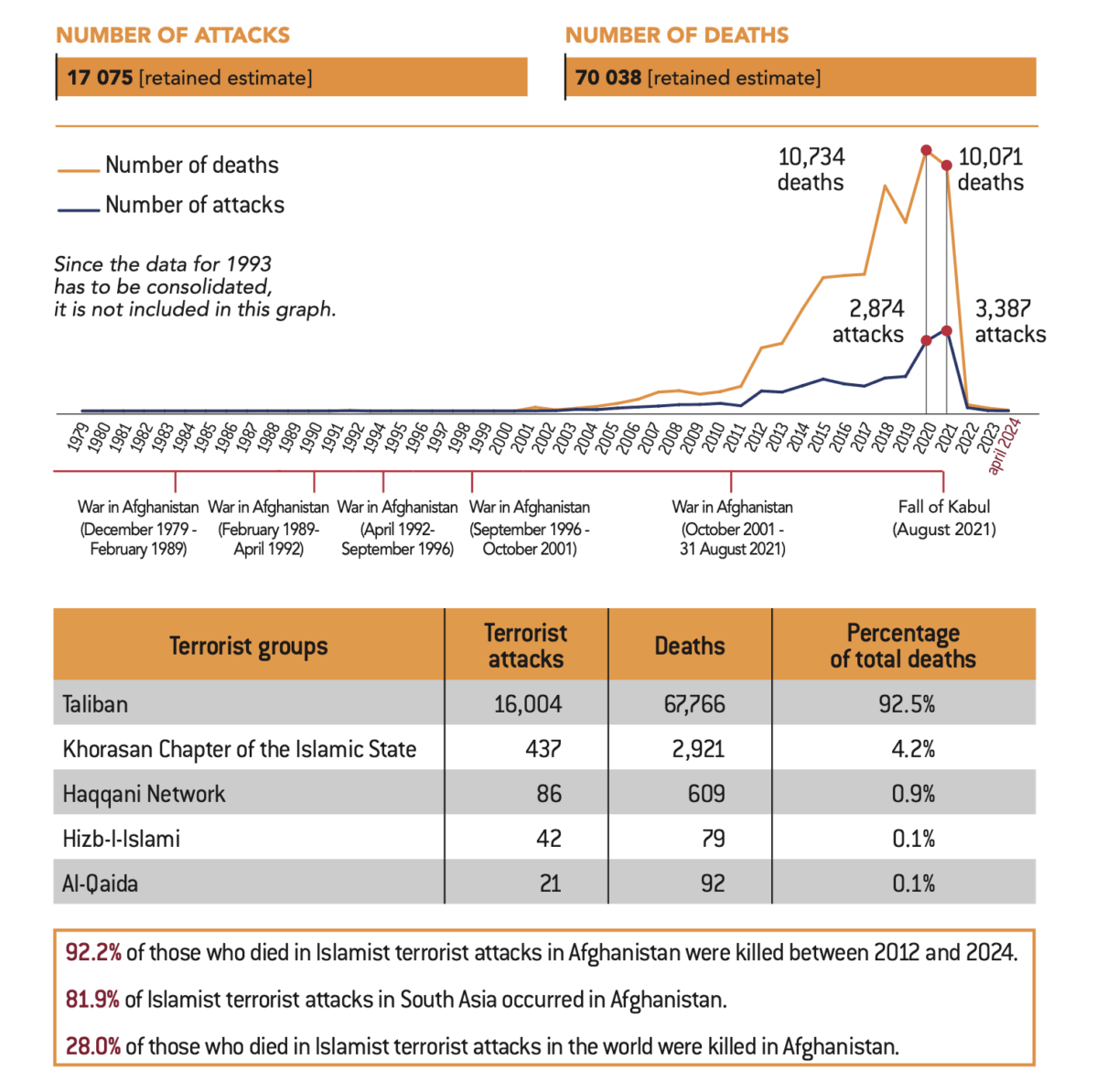

Figure 5 – Islamist terrorist attacks in Afghanistan (1979-2024)

Source :

Islamist terrorist attacks in the world, 1979-2024, Fondapol, October 2024, p. 67. [online].

Note: In all three editions of our study (2019, 2021, 2024), Afghanistan consistently ranked first as the country most affected by terrorist attacks, both in the number of attacks and deaths.

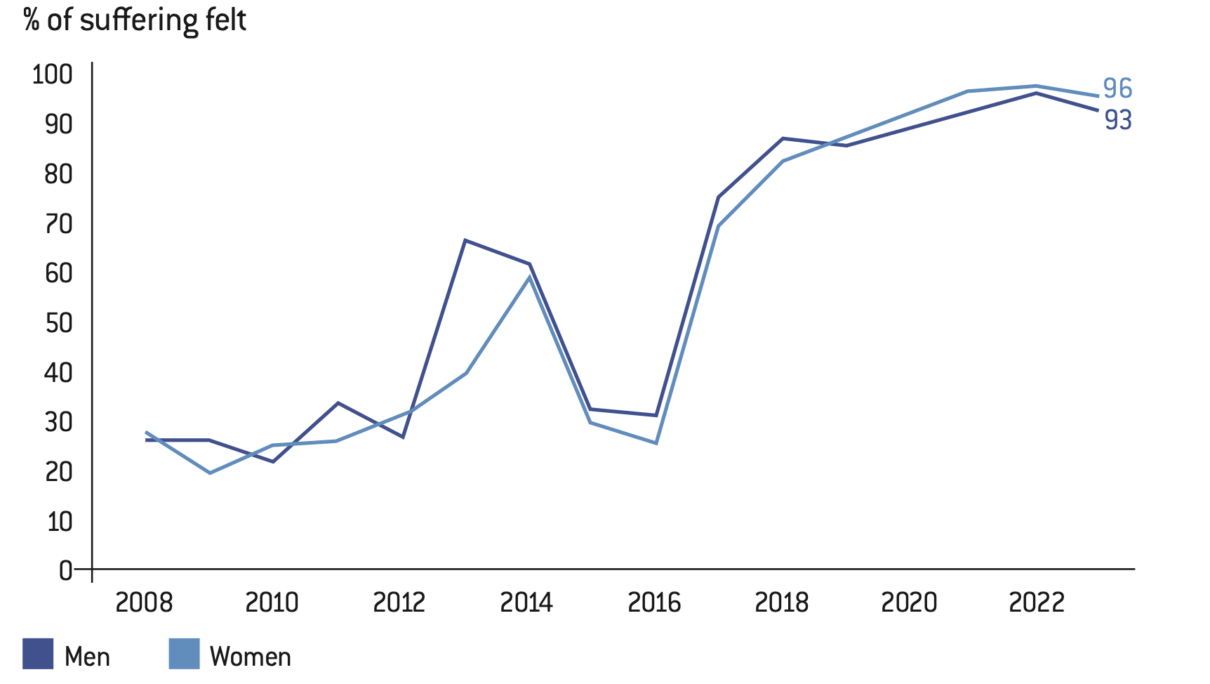

Figure 6 – Afghan men and women suffering universally in 2023

Source :

Khorshied Nusratty and Julie Ray, ‘Freedom Fades, Suffering Remains for Women in Afghanistan’, Gallup, 10 November 2023 [online].

Something else was at play. Overall, the situation had remained constant. It was indeed the ‘Syrian opportunity’, i.e. the flight of Syrians to Europe, that was the driving force behind Afghan asylum. The route to Europe was ‘opened up’ by the Syrian exodus, which created a geopolitical window of opportunity for migration that other populations, such as Afghans, were able to use.

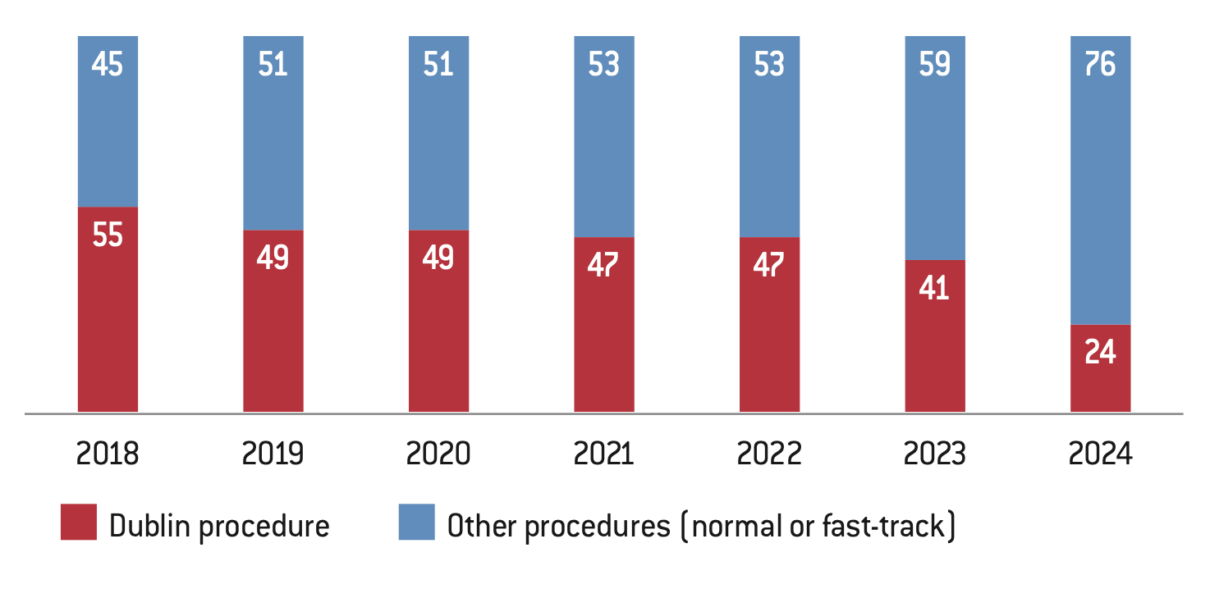

This period thus saw the beginning of a migration to Europe via Iran, Pakistan and Turkey, which became transit countries to some extent, even though many Afghans continued to remain there. People left these countries as soon as they could to reach Western or Northern Europe. When they reach the European Union, immigrants have to apply for asylum in their first country of entry, then responsible for reviewing their applications and granting them asylum or deporting them to their country of origin. These rules were clarified by the EU Member States at a meeting in Dublin, hence the name ‘Dublin Agreements’.

Within the European Union, Afghan settlements reconfigure themselves in what is known in administrative jargon as ‘secondary movements’. A secondary movement is the movement of a person from the Member State responsible for an asylum application to another Member State. This phenomenon severely damaged the Dublin system during the migratory crisis of 2015 and 2016, as it disrupted the process of determining the Member State responsible and undermined the principle of a single asylum application within the EU.

| THE DUBLIN AGREEMENTS

When a State receives a person wishing to apply for asylum, it must check whether another State is responsible for the application, in particular if the applicant has transited through that State or has already filed an asylum application there. The Dublin Regulation was initially intended to make the first country of entry responsible and to reassure secondary destination countries within the EU. The Dublin Regulation has proved flawed because it does not prevent a person from reapplying for asylum in another country after 18 months. Furthermore, asylum seekers awaiting return to the country of first entry, i.e. the country where they were first registered upon arrival, must receive asylum seeker benefits and accommodation. It is this weakness that the new Migration Pact seeks to correct, not by prohibiting the submission of a new asylum application, but by depriving applicants who fall under the responsibility of another State of all resources in order to force them to return there. Source: The Dublin Regulation: ‘Summary note: Secondary movements of beneficiaries of international protection’, European Migration Network (EMN), 20 September 2022 [online]. |

Secondary movements

Eurostat, “Asylum applicants by type, citizenship, age and sex – annual aggregated data”, updated on 22 May 2025 [online].

Before the fall of Kabul in 2021, recognition rates for Afghans – i.e. the proportion of decisions granting protection out of the total number of decisions – varied greatly depending on the EU Member States responsible for examining asylum applications. For example, Italy granted international protection to 93.8% of Afghan asylum seekers in 2020, while Sweden’s rate hovered around 40%. France’s rate was around 80%.

These secondary movements also stem from another major weakness: differences in protection rates across the European Union. The protection rate corresponds to the number of people protected in relation to the number of those seeking protection under the Geneva Convention on the right to asylum. This rate is not harmonised across all Member States. In 2024 (two to three years after the fall of Kabul), the variation in the protection rate for Afghans at first instance ranges from 11% to 92% in EU countries.9

Since 2015, Afghan asylum seekers have been prompted to move to the countries offering the most favourable conditions. They have been able to do so in the absence of unified and homogeneous assessment criteria, a European list of countries of origin classifying their level of security and shared risk assessments of countries.

The rules laid down in the Dublin agreements do not prevent asylum seekers who have been rejected in one EU country from moving to another. As a result, many Afghans already present in the EU, in Greece but also in Hungary, for example, are turning to northern European countries. For example, while Hungary registered 46,000 Afghan applications in 2015, this figure fell to just 11,000 in 2016. This decrease can also be explained by the Hungarian authorities’ decision to close the Hungarian-Serbian and Hungarian-Croatian borders, while at the same time opening the Austrian-Hungarian and German-Austrian borders. Afghans in Hungary were then able to leave the country via the North. The closure of Hungary’s Southern borders led to an increase in crossings via Croatia. While asylum applications in this country were almost non-existent in 2015, they rose to 700 in 2016. However, these applications did not mean that migrants were giving up on continuing their journey further West and North, via Slovenia. From 2016 onwards, this country also recorded several hundred applications. But it was in the West and North that the phenomenon was particularly noticeable.

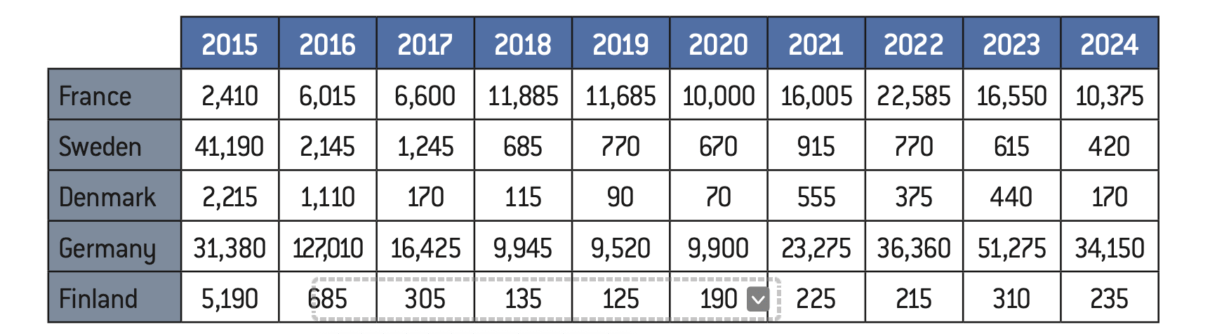

In Sweden, asylum applications rose from 3,000 in 2014 to 41,000 in 2015. Faced with this massive influx, the country reacted quickly by adopting restrictive policies: it curtailed the rights of asylum seekers, limited recognition of the need for protection, and stepped up deportations of rejected applicants.10 Border controls, reduced refugee rights, lower protection rates for Afghan asylum seekers and deportations to Kabul were among the measures aimed at deterring Afghans from seeking asylum.11 The deterrent effect has been noticeable since 2016, with Sweden recording only 3,000 Afghan applications, confirming that there is a clear link between internal reception or closure policies and the number of arrivals.

The same is true for Denmark. In 2015, this country registered around 21,000 asylum applications. While the majority were Syrian, 3,500 Afghans were also among the arrivals. In 2019, the Danish authorities introduced a ‘zero refugee’ policy (the country is not a signatory to the Dublin Conventions). In 2020, Denmark registered only 1,500 asylum applications, and 860 in 2024, of which Afghans have virtually disappeared. Norway and Finland are experiencing similar developments.

Figure 7 – Afghan asylum applications by EU countries

Source :

‘Asylum applicants by type, citizenship, age and sex – annual aggregated data’, Eurostat [online].

‘We can do it’ were the words spoken by Angela Merkel on 31 August 2015 when she welcomed with open arms, without administrative formalities, the million Syrian, Afghan and Iraqi migrants who arrived by train in Germany.

The closure policy of the Northern European countries is causing a shift towards Western Europe. Not only are new entrants to the Schengen area no longer rushing to the Scandinavian countries, but Germany is also becoming less attractive. After Merkel’s ‘wir schaffen das’12 that made Germany the first destination for Afghans, Afghan asylum applications declined from 127,000 in 2016 to 18,000 in 2017.

France, a country of asylum for afghans

See the report by the Inspection Générale de l’Administration (IGA), Jean Aribaud and Jérôme Vignon, ‘Report to the Minister of the Interior on the situation of migrants in the Calais area’, Ministry of the Interior, June 2015 [online]. The latest figures at the time of dismantling reported the presence of 7,000 migrants in the Lande de Calais slum.

The British first arrived there in 1839 to wage the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842), which they lost. They then obtained accreditation for a permanent diplomatic mission in Kabul to counterbalance Russian influence. Subsequently, Great Britain became one of the countries of asylum for Afghans.

The Afghan royal family, particularly under the reign of Mohammad Zahir Shah, had close ties with France. King Mohammad Zahir Shah, who reigned from 1933 to 1973, was partly educated in France. This education influenced his cultural openness and modernising approach to the Kingdom. Several members of the royal family spoke French and were openly Francophile.

Ukrainians are applying for asylum while benefiting from temporary protection, a measure activated by the EU that entitles them to benefits, the right to work immediately, and social rights, advantages that asylum seekers do not have. For reasons undoubtedly linked to the French authorities’ decision to require them to renew their temporary protected status every six months, some Ukrainians are applying for asylum. This is an anomaly in France, as 50% of Ukrainian asylum applications within the EU are registered in France.

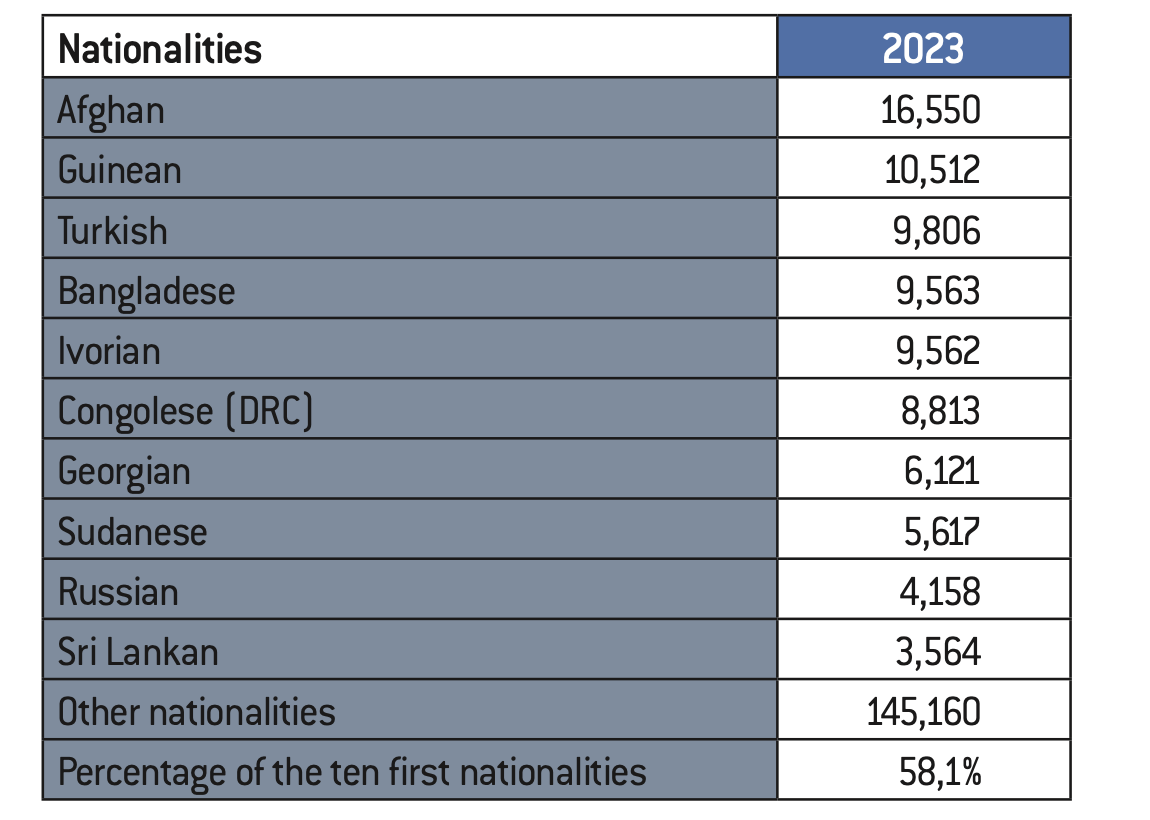

In this context, after Germany, France has been receiving secondary movements of Afghans since 2015. Until then, France had mainly been considered a country of transit, particularly to the United Kingdom, hence the strong presence of Afghans in Calais from 2016 onwards, before the dismantling of the Calais refugee camp.13 The United Kingdom’s attractiveness results from its historical ties with Afghanistan.14 The Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates that there were 79,000 people born in Afghanistan living in the United Kingdom in 2019. This figure rose to 85,693 in the 2021 census for England and Wales and to 116,167 in 2024. In 2024, nearly 8,500 Afghans applied for asylum there, representing almost 8% of the total. Since 2015, Afghans have been the most represented nationality among arrivals by ‘small boats’. In 2024, 5,900 arrived in England by this means. But unlike France, Afghan migration to the UK has been spread over a longer period. Between 1994 and 2006, around 36,000 Afghans sought asylum in the United Kingdom. Afghan asylum applications in France did not exceed 472 in 2014. This low number can also be seen as the result of virtually non-existent ties between Afghanistan and France. Although cooperation in the field of archaeology has existed since the 1920s,15 the most recent tangible link with France was our country’s participation in the military coalition between 2001 and 2012. However, against all odds, the number of asylum applications from Afghanistan rose exponentially from 2015 onwards. In 2015, 2,200 applications were registered. In 2016, there were just under 6,000 applications (5,989). In 2023, there were 17,550 initial applications, including 812 unaccompanied minors (UAMs), compared to 9,455 in 2018. In 2023, these accounted for 61% of all UAMs who applied for asylum. Afghans are the largest group of asylum seekers in France. More than 13,000 filed applications in 2024, surpassed only by the exceptional number of applications from Ukrainians, who now rank first among first-time applicants.16

Source :

« Rapport d’activité 2023. À l’écoute du monde », OFPRA, 9 July 2024, p. 53 [online].

Figure 9 – First-time asylum applicants in France by nationalities

Source :

« Les demandeurs d’asiles », French Ministry of the Interior, 4 February 2025, fig. 1.3. [online].

The number of people seeking asylum in Sweden in 2024 rose to 9,645, the lowest figure since 1996 and a 42% decrease compared to 2022. In 2015, at the height of the migrant crisis, Sweden registered some 162,877 asylum seekers, the highest number per capita in the EU. ‘Asylum seekers 2002-2024’, Statistics Sweden, 21 February 2025 [online].

In 2024, the OFPRA protection rate stood at 67.4%. The overall protection rate (after appeal to the CNDA) was 79.7%. Women accounted for one-third of asylum applications in 2024.

The press reported on this issue: ‘Swedish families and citizens are advising the young Afghans they have helped, housed and supported to go to France, where the acceptance rate for asylum applications filed by Afghans is high. The migrant support network, which operates mainly through parishes and word of mouth, leads these young men to knock on the door of the Swedish Church in Paris when they reach the end of their journey.’ See Delphine Evenou, ‘Les réfugiés afghans de l’église suédoise de Paris’ (Afghan refugees of the Swedish Church in Paris), France Inter, 15 October 2018 [online].

Office Français de I’Immigration et de I’Intégration (OFII) data.

While other European Union countries are restricting access to asylum, Afghan demands in France remain high, driven by significantly higher approval rates from the OFPRA (Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et des Apatrides) than elsewhere in Europe, with the exception of Italy, where, however, reception conditions remain less favourable than on the other side of the Alps.

France’s more favourable provisions remain in place. In 2024, the average protection rate for Afghans in Europe stood at 63%, remaining very low in Sweden at 40%,17 but above 70% in France.18 It was this type of disparity that had already motivated Afghans to leave Sweden to try their luck in France as a ‘rebound’ country in the context of the secondary movements already described.19 Between 2018 and 2023, about 41% to 55% of Afghans who filed an initial asylum application in France had already filed one elsewhere in the EU, mainly in Sweden or Germany. This proportion fell to 24% in 2024.20

Figure 10 – Breakdown by procedure of initial asylum applications from Afghanistan in France

The challenge of employability

However, the Afghan community cannot be reduced to those in possession of a residence permit alone. In addition to adults, there are those whose minority status means that they are not eligible for a residence permit, and those who have acquired French nationality.

Not to mention France’s claim to the title of Protector of Christians in the Ottoman Empire since the reign of Francis I and the fact that there is a long-standing French-speaking tradition there.

Afghans tend to gather in Turkish mosques.

20% of asylum seekers’ accommodation, which comprises nearly 120,000 places, is located in departments with fewer than 500,000 inhabitants (OFII annual report for 2023).

The data presented was compiled from questions asked to 69,115 Afghans who had been granted refugee or subsidiary protection status.

Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et des Apatrides (OFPRA) report for 2023, Annex VII, p. 132.

Due to the small number of Afghans, there are no statistics on the employment rate. However, international comparisons with more dynamic labour markets suggest that the difficulties are likely to be comparable. In Austria, the unemployment rate among Afghans was 20.6% in 2022, while in Germany it was 29.9% in October 2024. See: „Zahlen, Daten, Fakten: Neue ÖIF-Factsheets über Syrer/innen und Afghan/innen in Österreich” (Figures, data, facts: New ÖIF fact sheets on Syrians and Afghans in Austria), Ôsterreichischer Integrations Fonds, 2 June 2023 [online] ; „Migration une Arbeitsmarkt” (Migration and the labour market), Bundesagentur für Arbeit [online].

AGIR stands for ‘Accompagnement global et individualisé des réfugiés’ (Comprehensive and individualised support for refugees). In 2024, €47 million was allocated to the AGIR programme. For more detailed information on this programme, see Clément Soulignac and Alessio Raskine, ‘IM n° 113 – Les trajectoires professionnelles et résidentielles des réfugiés accompagnés par le programme AGIR’ (The professional and residential trajectories of refugees supported by the AGIR programme), Ministry of the Interior, 13 December 2024 [online].

The largest Afghan community in Western Europe lives in Germany. In 2024, the German Federal Statistical Office estimated that there were 442,020 people of Afghan origin living in Germany. See ‘Foreign population by place of birth and selected citizenships’, Statistiches Bundesamt, 10 April 2025 [online].

In ten years, the community of Afghans living in France has risen to around 100,000 people, three-quarters of whom arrived after 2016. The number of adults alone with residence permits in France was 89,000 in 2024.21 By way of comparison, in 2015 the total number of protected people did not exceed 4,500 (4,397). In 2007, INSEE numbered only 1,600 Afghans on French territory.22 In addition to the current beneficiaries of residence permits, there are 10,376 people who were in the OFPRA procedure in 2024 and who will be issued with a residence permit in 2025 or 2026, depending on the length of the investigation. However, they are already present on French territory as they are in the process of applying for asylum in France. During the first five months of 2025, more than 3,000 Afghan adults registered as asylum seekers. Those data confirms that, in just a few years, a group of well over 100,000 people has formed on our territory.

Afghans are now among the top ten nationalities holding residence permits in France. Their number even exceeds that of Syrians holding residence permits, with twice as many Afghans, and that in spite of the deeper and older historical ties France and Syria have forged, following the French Mandate for Syria (1920-1946).23

Afghans remain socially, culturally and religiously marginalised, as believers find little solidarity within a Muslim world dominated in France by North Africans.24 Small and medium-sized towns as unexpected as Aurillac, Vannes and Colmar have a significant Afghan presence. This confirms the effectiveness of the asylum seeker distribution policy implemented by the public authorities through the national reception system managed by the Office Français de l’Immigration et de l’Intégration (OFII).25 After obtaining protection, Afghan refugees remain in the city or department where the OFII had initially directed them for accommodation.

Those protected by the OFPRA automatically receive a four-year residence permit (for beneficiaries of subsidiary protection) or a ten-year residence card (for refugees). In theory, they are not required to sign the Republican Integration Contract (CIR), unlike other new residence permit holders, with the exception of Algerian nationals. However, in practice, the OFII systematically directs them to sign this contract, which gives them access to free French language courses and employment support.

This support enables to draw up a social profile of the Afghan refugees. Known as the ‘end-of-CIR review’, the review of their situation is especially useful to get a holistic view of this group, for it is carried out 12 to 18 months after their first contact with the OFII for the implementation of their integration contract.

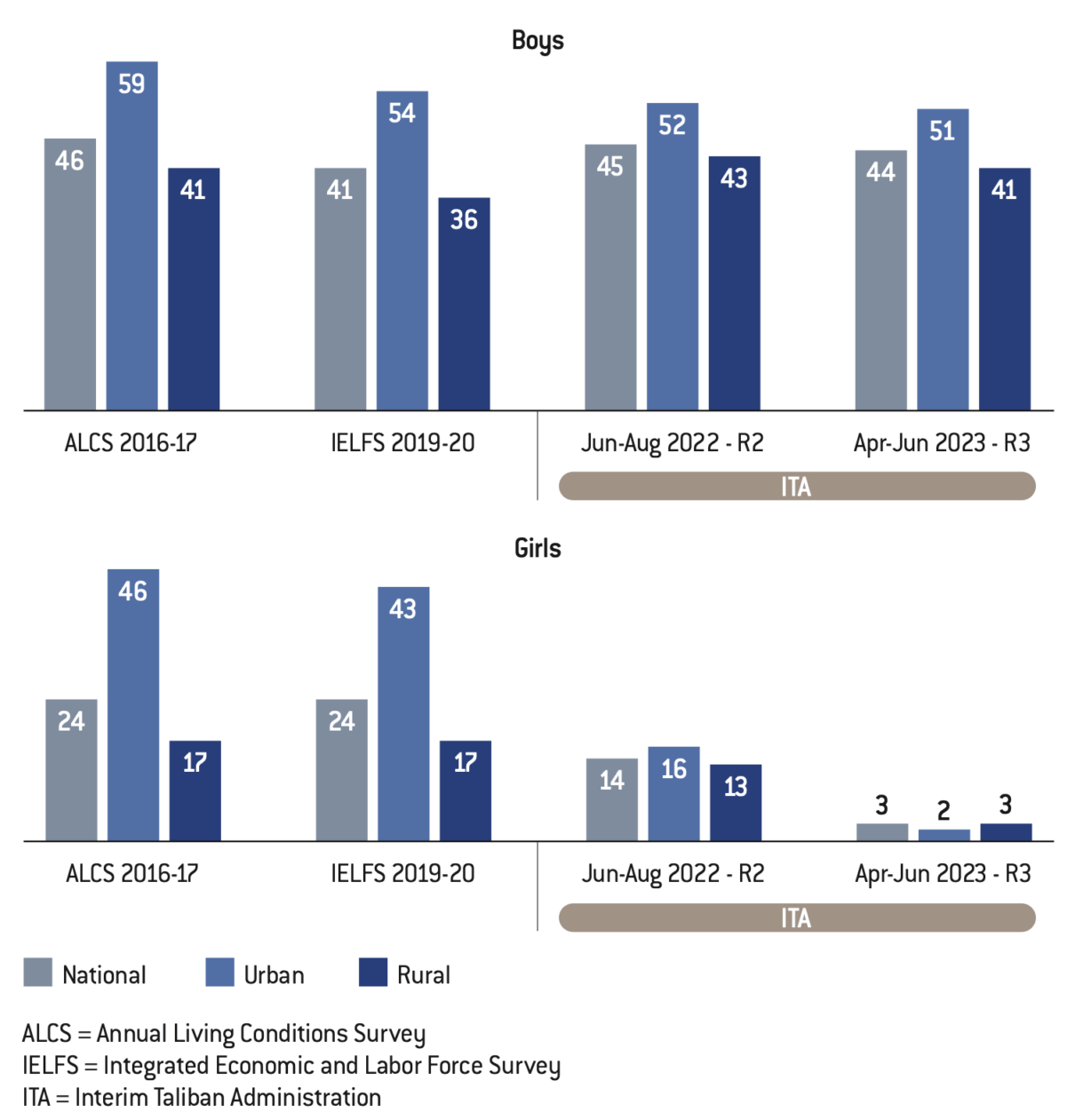

The main characteristic that emerges is the low level of education and training within the Afghan group. More than 40% of those surveyed said they had never been to school.26 Twenty years of ‘Islamic republic’ under Western influence have not significantly improved the education of Afghans, whether they come from rural or urban areas. In 2021, before the fall of Kabul, only slightly more than a quarter of the Afghan population lived in urban areas. Thirty per cent of children aged 5 to 17 were recorded as not attending school. The average age of Afghan asylum seekers (adults) in France was 27.4 in 202327 which implies that the moment they eventually started school was during the 20 years of Western presence. This therefore shows the extent of the Western failure to support development through education.

Nearly 19% of Afghans report having no more than a primary school education, and even a level lower than our primary school certificate, due to difficulties in reading and writing. And 10% cannot read or write in their mother tongue. Finally, 17% report having a level of education higher than the baccalaureate.

This has an impact on their social integration and access to employment. As a result, 18 months after they signed the CIR and the end of French language courses, 57% of them reported being unemployed.28 This is largely due to the fact that only slightly more than half of learners of French as a foreign language reach level A1, which corresponds to a basic level of French. These figures justify the efforts made by the administration to help them. In 2024, 30% of the beneficiaries of the AGIR programme,29 which aims to support refugees in accessing training, employment and accommodation, were Afghans.

Low levels of education and difficulties in learning the language suggest that, if data were available, it would probably highlight the significant difficulties of integration. However, such social data is not available in our country, as Afghans have been included in the general category of people from Asia in France Travail data.

Other countries, however, have implemented more detailed monitoring. In Germany, another country with a large Afghan presence with an estimated population of 425,000 people,30 the unemployment rate among Afghans of both sexes was 30% in October 2024, six times higher than that of Germans (5.3%). It is as high as 53% among Afghan women. The employment rate for Afghans of both sexes – i.e. the proportion of those of working age who are actually in employment – is 42%, which is almost 30 points lower than the employment rate for Germans (71%). The under-integration of Afghan women into the German labour market is particularly noticeable: only 21% of Afghan women of working age are in employment, almost 50 points lower than German women (70%), which confirms the finding of a very strong cultural gap in this area and puts into doubt the idea that asylum flows could provide host countries with employable labour.31

A significant public order issue

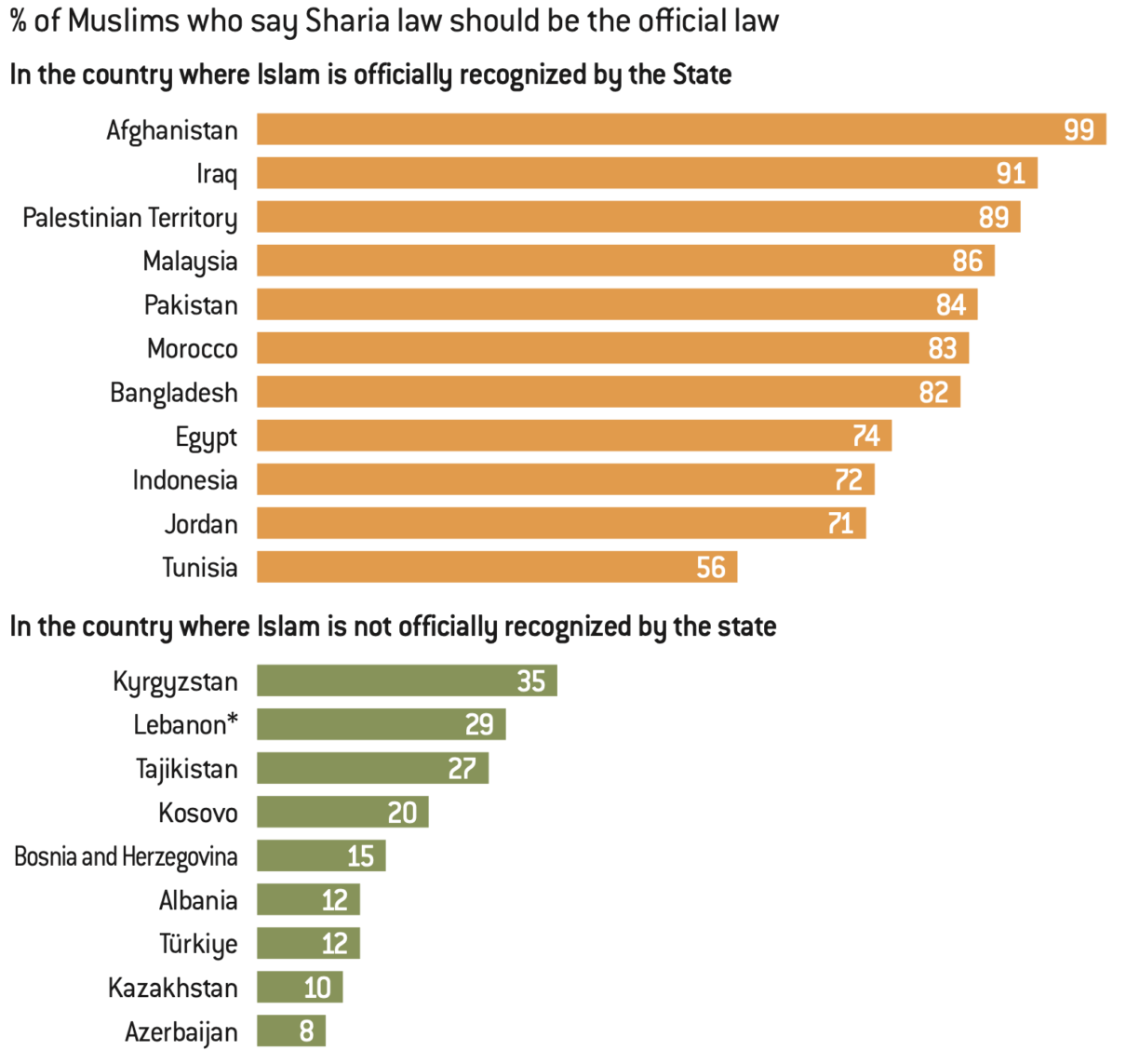

A 2013 Pew Research Center study highlighted the difficulty of integrating Afghans, 99% of whom said they supported Sharia law and 85% supported stoning for adultery.32

Figure 11 – Support to Sharia as official law

Source :

The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society, Pew Research Center, 30 April 2013 [online].

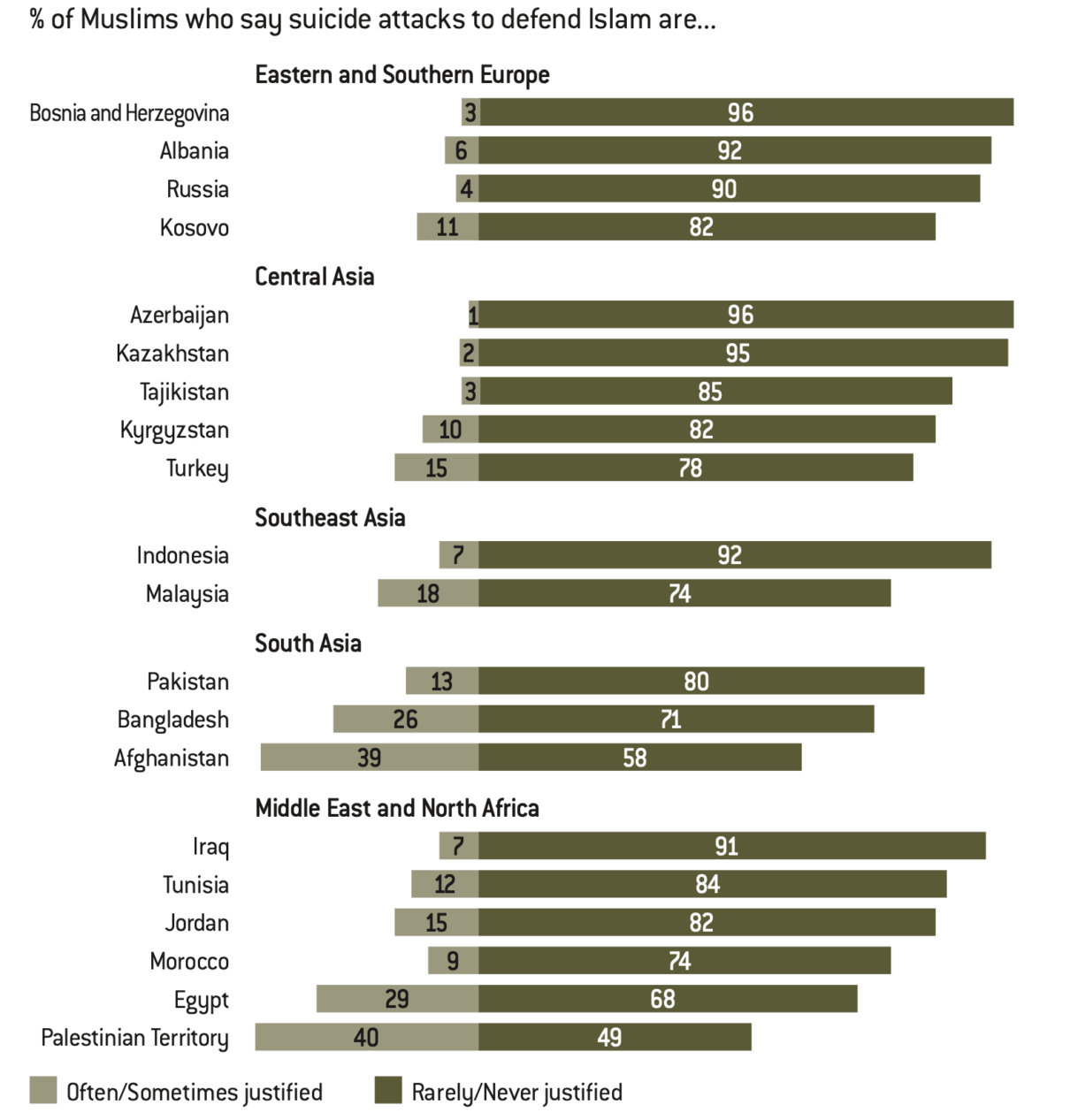

Figure 12 – Support to suicide bombings

Source :

The World’s Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society, Pew Research Center, 30 April 2013 [online].

Among prisoners, Afghans are included in the general category ‘Asia-Oceania’.

„T62 Straftaten und Staatsangehörigkeit nichtdeutscher Tatverdächtiger (V1.0)”, Bundeskriminalamt (Criminal Police Office) [online]. It could be added to public order disturbances in France that, of the 15,872 administrative investigations carried out in 2017 (compared to 3,742 in 2015) for the application of subsidiary protection exclusion clauses, 47% concerned Afghans. See Catherine Teitgen-Colly, Le droit d’asile, PUF, 2025, p. 50. Afghans were also the nationality most affected by withdrawals and terminations of protection status in 2023. See ‘Activity Report 2023. Listening to the world’, OFPRA, 9 July 2024, Annex 13, p. 145 [online].

As with other nationalities, integration difficulties are made obvious and measured by involvement in public order offences. France does not have statistics available in this area, except that foreigners account for 25% of convicted prisoners, while they make up 8.2% of the total population.33 German data show that, while Afghans accounted for only 0.5% of the population of Germany at the end of 2024, they were five times more likely to be charged with all offences recorded in that country in 2024 (2.3%). While some of this crime may be linked to survival needs or precarious living conditions, this overrepresentation is particularly marked for crimes and offences of a sexual nature. This may be partly linked to the difficulties in gender relations and the devaluation of women, a major cultural issue in Afghanistan.

In Germany, Afghans are 21 times more likely to be charged with sexual abuse of minors. They accounted for 10.5% of all such charges, compared with 0.5% of the general population; 16 times more likely to be charged with soliciting sexual acts from minors; 16 times more likely to be accused of pimping; 14 times more likely to be involved in the distribution, acquisition, possession and production of child pornography; 10 times more likely to be involved in violent offences against persons (‘crimes of brutality and crimes against individual freedom’).

Afghans are also over-represented in mafia-type crimes. They are nine times more likely to be involved in armed robberies against financial institutions (banks/savings banks); eight times more likely to be involved in ‘robberies in post offices and postal agencies’; and seven times more likely to be involved in ‘robberies and extortion of funds from/against cash transporters’.34 This criminal reality leading countries to seek ways of deporting to Afghanistan those who have broken the hospitality pact through their actions, particularly those who are a threat to public order. Faced with this necessity, France had come up against a ban on returning Afghans listed as ‘S files’ to Kabul because they were Taliban. Only Germany has announced that it will circumvent this ban.35

Afghan women made invisible

In January 2023, these operations involved 6,131 people during evacuations that took place over several months. The ratio of women to men was around 50%. Since 2023, only occasional operations have remained, involving women only. See: ‘Operation APAGAN: welcoming refugees threatened by the Taliban,’ Ministry of the Interior, 23 January 2023 [online].

See the article by Catherine Maia, « La reconnaissance par la CJUE de l’appartenance des femmes à un groupe social susceptible d’ouvrir droit au statut de réfugié » (Recognition by the CJEU of women’s membership of a social group that may give rise to refugee status), Club des juristes, 1 March 2024 [online]. On 16 January 2024, in its WS judgment in case C-621/21 in response to a request for a preliminary ruling from the Bulgarian court, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) provided important clarification on the grounds allowing women who are victims of violence in their country to benefit from international protection. Sitting in Grand Chamber, the CJEU ruled that women, as a group, may be regarded as belonging to a social group within the meaning of Directive 2011/95/EU (the ‘Qualification Directive’) of the European Union (EU) and be granted refugee status if the conditions laid down in that directive are met. This is the case where, in their country of origin, they are exposed, because of their sex, to physical or mental violence, including sexual and domestic violence. If the conditions for granting refugee status are not met, they may be granted subsidiary protection status, in particular where they face a real risk of being killed or subjected to violence.

Between 2015 and 2024, 85% of asylum seekers were men. By comparison, over the same period, of the 1,064,946 people who signed a CIR, 47.81% were women. This finding further highlights the male dominance among Afghan immigrants.

Women account for less than 18% of all Afghans living in France with a residence permit. Gender diversity among Afghan asylum seekers was only seen during operations carried out between 2021 and 2022, after the fall of Kabul, as part of the APAGAN Operations.36

However, there has been a certain increase in the number of women through family reunification. Family reunification concerns a person designated as a partner by the asylum seeker, which entitles them to join them after obtaining refugee status or subsidiary protection. Family reunification concerns a person who has been declared as a spouse after obtaining asylum; after gaining nationality, the reunification procedure involves granting the title of ‘French family’. Between 2015 and 2024, 1,398 people arrived through family reunification and signed a CIR, of which 601 through family reunification. Women account for 80% of this scheme. There has been an acceleration in family reunifications. In 2015, only 25 were recorded. Until 2020, the number remained below 200 per year. There were 479 in 2022, after the Covid period, 701 in 2023 and 1,094 in 2024. Finally, 410 Afghan women arrived in France as wives of French nationals.

This low number of women deserves to be analysed, especially since, according to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and the National Court of Asylum (Cour Nationale du Droit d’Asile – CNDA), they constitute a ‘social group’ that is collectively eligible for asylum.37 Of the 600,000 people of all nationalities currently under protection, women account for 41%. This is despite the fact that their migration routes generally pass through the appalling areas of Libya, Niger and, to a lesser extent, Tunisia. African migration across the Mediterranean is more mixed. For example, 46% of residents from the African continent, out of around 220,000 people receiving protection, are female residents. Some nationalities are even predominantly represented by women. For example, 70% of Ivorians are women. Admittedly, the protection rate for Ivorian men is low, which would explain this discrepancy.

There are more Senegalese women receiving protection in France (60%) than Senegalese men, and more Nigerian women (64%) than Nigerian men. It should be noted that ‘human trafficking’, which in this case essentially means being forced into prostitution by members of their own community, largely explains this over-representation of women.

Women account for 33% of protection beneficiaries from Asia, out of more than 235,000 protected persons, which is a lower percentage than for African migrants. However, despite this, the over-representation of Afghan men is surprising when compared to other countries in the same geographical area. Among the tens of thousands of Syrians in France, women account for more than 46% of the total, while among Sri Lankans, the figure is 37%.

The low number of Afghan women in France cannot be explained solely by the difficulties of the migration routes. It also reflects a deeply rooted mentality that continues to permeate Afghan men, even those who have sought refuge abroad. Although there have been attempts to improve the status of women in Afghanistan as part of a drive towards modernisation, these have been short-lived, with any gains quickly reversed until they disappeared completely in 2021. For example, the age of marriage for girls was set at 18 and polygamy was banned in 1928 under the impetus of Queen Soraya, wife of King Amanullah Khan (reg. 1919-1928), who did not wear the veil at all times. The education of girls was encouraged. It was also decided that girls would be sent abroad to continue their studies. These reforms were called into question in 1929 under the reign of Nadir Shah (1929-1933). He closed all girls’ schools, foreshadowing the measure just taken by the Taliban. A new era begun under the reign of Mohammad Zaher Shah (reg. 1933-1973) during which girls returned to school and women gained access to public office and various professions. In 1959, wearing the hijab was declared optional. Women were represented in the Loya Jirga, the traditional Parliament, and entered Government.

This policy of social equality, part of a Marxist-inspired agenda, continued under the Communist Government that came to power in 1978. Equal rights for women and men were enshrined in law. Literacy became compulsory for women. They were encouraged to work. Kindergartens were set up. Women drove buses and, more generally, worked in the public services. The presence of women in public life was contested by religious forces. Weakened by internal struggles between communist factions and no longer able to count on the support of Soviet troops, the Communist Government was toppled by the Mujahideen in 1996. This marked the beginning of the first Taliban regime. It was a period of total subjugation for women, accompanied by all forms of violence.

Figure 13 – Secondary school attendance (age 13-18), by gender and area of residence

Source :

‘Afghanistan Welfare Monitoring Survey (AWMS)’, World Bank, October 2023, fig. 13, p. 18. [online].

A strict separation between women and men was established. Women were not allowed to leave their homes without being accompanied by a mahram, a male member of the family. The new restriction imposed by the Taliban prevented women and girls from fleeing to the Pakistani border. Girls’ education was called into question. Women who disobeyed the rules in force were publicly flogged. Today, the measures are becoming even tougher, under the pretext that women’s emancipation is the result of Western influence imposed since 2001.

The Taliban therefore want to roll back the gains that have been made and return to the country’s long history of oppression of women. During the 20 years of republican rule that followed the fall of the Taliban in 2001, women’s rights were enshrined in the Constitution. Seats were reserved for them in Parliament. However, support for governments promoting a conservative vision of Islam, with the aim of appeasing both religious forces and part of the Taliban, prevented any real intellectual and cultural transformation in favour of equal rights for women.

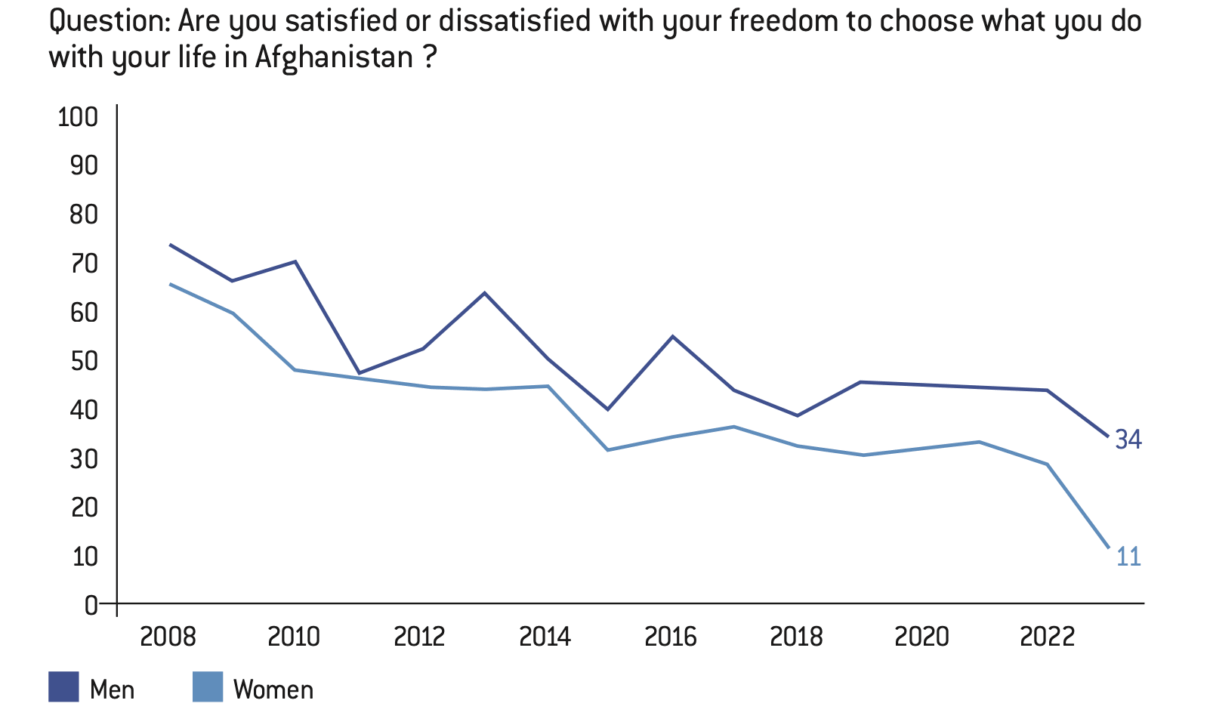

Figure 14 – Satisfaction with freedom in Afghanistan

Source :

Khorshied Nusratty and Julie Ray, ‘Freedom Fades, Suffering Remains for Women in Afghanistan’, Gallup, 10 November 2023 [online].

Improvements in women’s conditions have been limited to certain sectors of society. Their continued illiteracy has been enforced with little internal resistance. For many men, the subjugation of young girls through forced marriage and polygamy remains a source of pride, both in rural and urban areas. The view that women are mentally deficient, inferior and must be subjugated to men remains widespread among most Afghans, including some women. Because of these deeply rooted preconceptions, men who leave Afghanistan today, for a variety of reasons but primarily economic ones, rarely consider bringing women with them, even though women are not allowed to travel alone. This explains the particularly low proportion of women among protected Afghan groups.

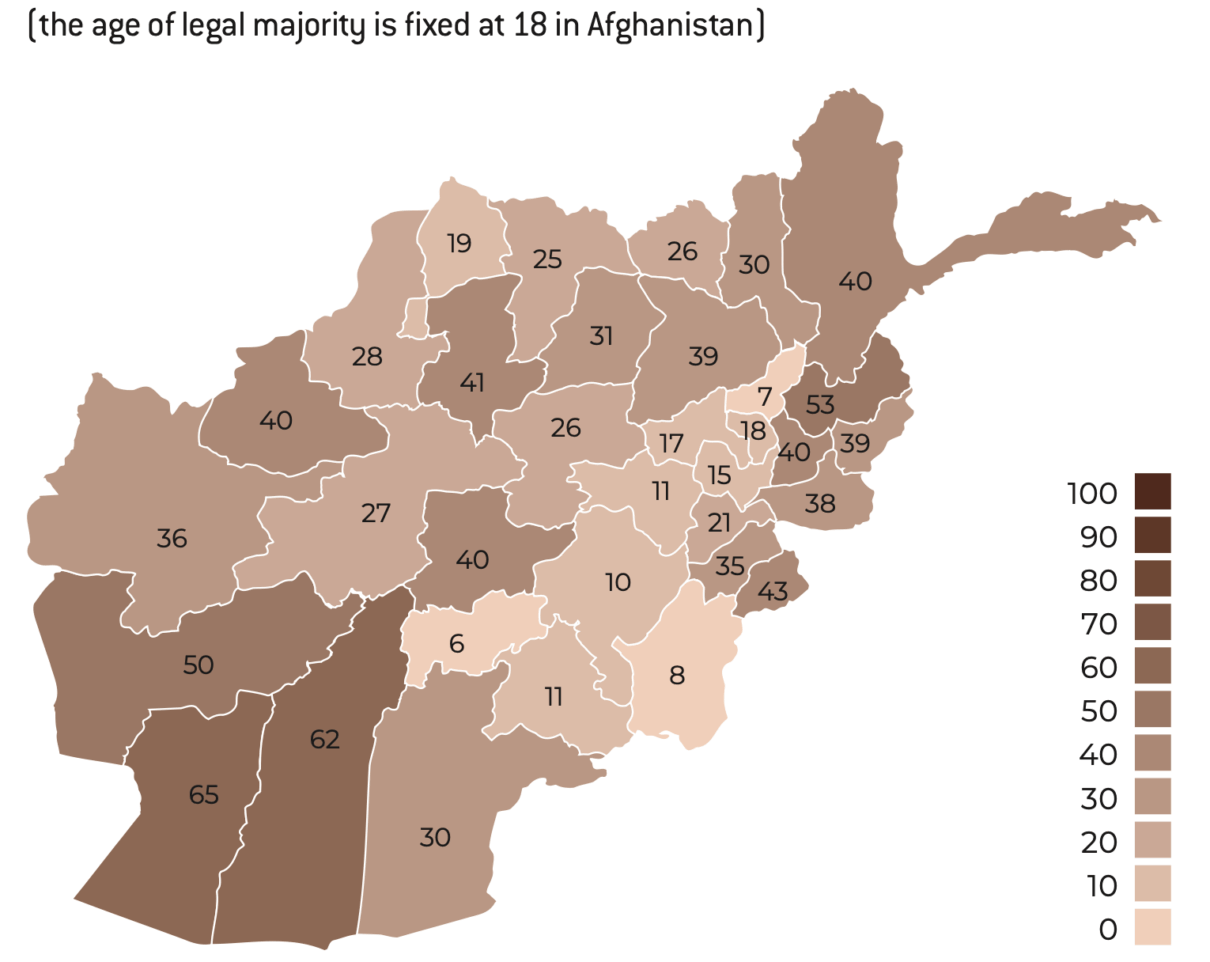

Figure 15 – Percentage of girls married under 18, by region in 2017

Source :

‘‘Afghanistan’’, The Child Marriage Data Portal [online].

This low female presence has consequences in terms of integration, as experience shows that integration through family and the presence of children often accelerates socialisation mechanisms through emotional bonds. Young men who have been granted asylum find it difficult to integrate the norms of civility governing relations between men and women, which leads to a proliferation of incidents, some serious, some less so, which are reported in the news. It is not easy to form legitimate emotional relationships when significant cultural differences come into play.

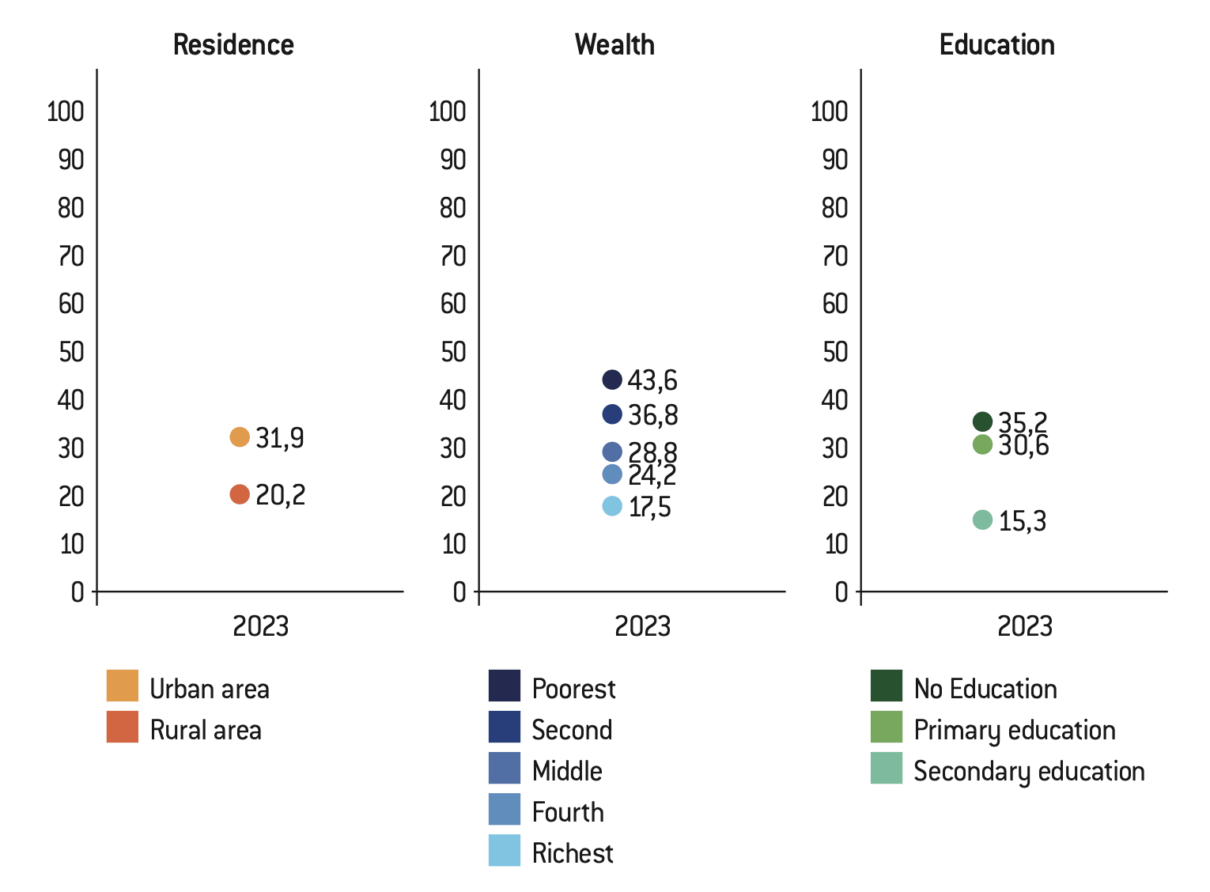

Figure 16 – Percentage of brides among minors by place of residence, wealth level and education level

Source :

“Afghanistan”, The Child Marriage Data Portal [online].

The Afghan migration highlights the obstacles to the integration of communities which, due to their rapid development, have not had the time necessary to fully embrace the values of the French Republic. Their integration has proved more difficult given that these waves of migration are occurring at a time when our integration structures are weakened. As a result, even more so than with previous waves of immigration, community structures have replaced political parties, trade unions in the workplace and even schools, and have become sorts of structures of isolation or anomie.

The host group, thus strengthened, becomes an obstacle to integration into a civic nation, especially as cultural and religious differences have become more entrenched. In this respect, although there are no precise studies on France, it is to be feared that there is little difference between the mentality of Afghans in France and those in Europe.

No comments.