The birth rate challenge

A Franco-Italian opinion surveyMain findings of the ‘Birth Challenge’ survey

Findings for France

Findings for Italy

Introduction

The French are worried by falling birth rates but their desire to have children remains high, especially among the under-35s

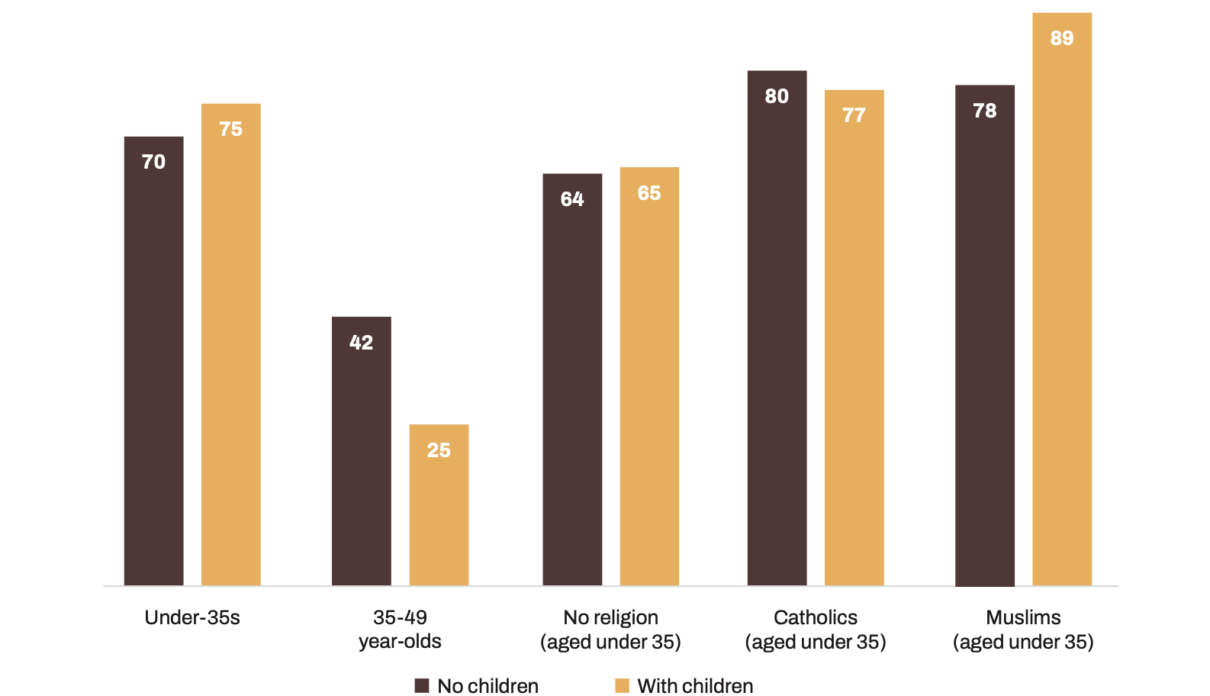

The vast majority (70%) of young French people (under 35) who do not have children want them, and 75% of young people who already have children want to have another. or more.

Most French people (59%) are concerned about falling birth rates, including young people (57%) and 47% of French people think that the Government is not doing enough on this issue (30% think it is doing enough)

Popular measures to support births: tax credits, childcare services and flexible working hours

Conclusion

The demographic crisis in Italy: between thwarted desires and hope for the future

Summary of the demographic situation in Italy

Motherhood and fatherhood: between desire and fear

Work-life balance : how to reconcile work with parenthood?

Corporate social protection, a lever for demographic growth

Enabling the future: the meaning of parenthood for Italians who want to have children

Conclusion

The birth rate challenge: A comparison between Italy and France on desire, freedom and responsibility

The demographic comparison between Italy and France

For a ‘demographic springtime’

Divergent sociologies

Conclusion

Summary

The rapid aging of the French and Italian populations and the continued decline in births are no longer abstract trends: they are realities with profound consequences for our societies. This joint survey by Fondapol and the Fondazione Magna Carta aims to go beyond simple observations to identify levers for action. By listening to citizens, it explores the link between the desire for parenthood, living conditions, and perceptions of the future, with a clear objective: to propose concrete ways to respond to a crisis that threatens the sustainability of our social systems, our territories, and the intergenerational bond.

The survey reveals a clear divide between France and Italy. While the desire for children persists in France, thanks in part to a more favourable institutional environment, Italy, faced with a sense of abandonment and structural difficulties, is seeing a growing proportion of its population give up on parenthood. This renunciation is not inevitable: it is the result of economic, professional, and symbolic obstacles. What is at stake is the ability of our societies to make having children once again possible, and desirable.

Respondents express clear expectations. In France, respondents favour solutions that allow them to reconcile work and family life: nurseries, flexible working hours, and work-from-home. In Italy, financial assistance (benefits, support for accessing housing, tax benefits) is the most common option. Immigration, sometimes presented as a response to the demographic deficit, deeply divides opinions in both countries. This panorama also reflects a shared awareness: without a strong commitment from public authorities and companies, demographic decline will continue.

By placing parenthood back at the heart of the debate, this survey calls for an ambitious policy response, tailored to the specificities of each country. Only by acting simultaneously on living conditions, social recognition of the role of parents, and equal opportunities between regions can a real demographic revival begin.

Fondation pour l'innovation politique,

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Fondazione Magna Carta,

Main findings of the ‘Birth Challenge’ survey

Findings for France

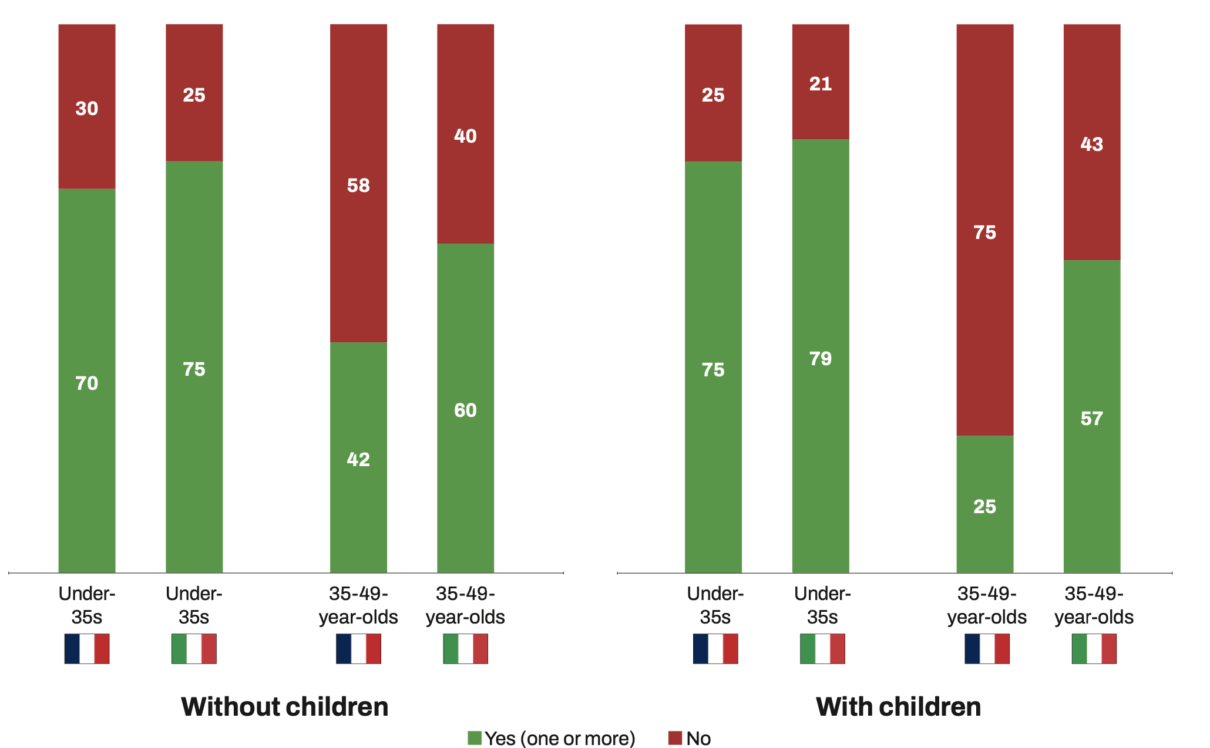

1. 70% of French people under 35 who have no children say they would like to have one or more and 75% of those who already have one or more children would like to have another one or more.

2. Religion influences the desire to have children among the under-35s in France. Among those who have no children, 80% of young Catholics and 78% of young Muslims want children, while among those who already have children, 89% of young Muslims and 77% of young Catholics want children.

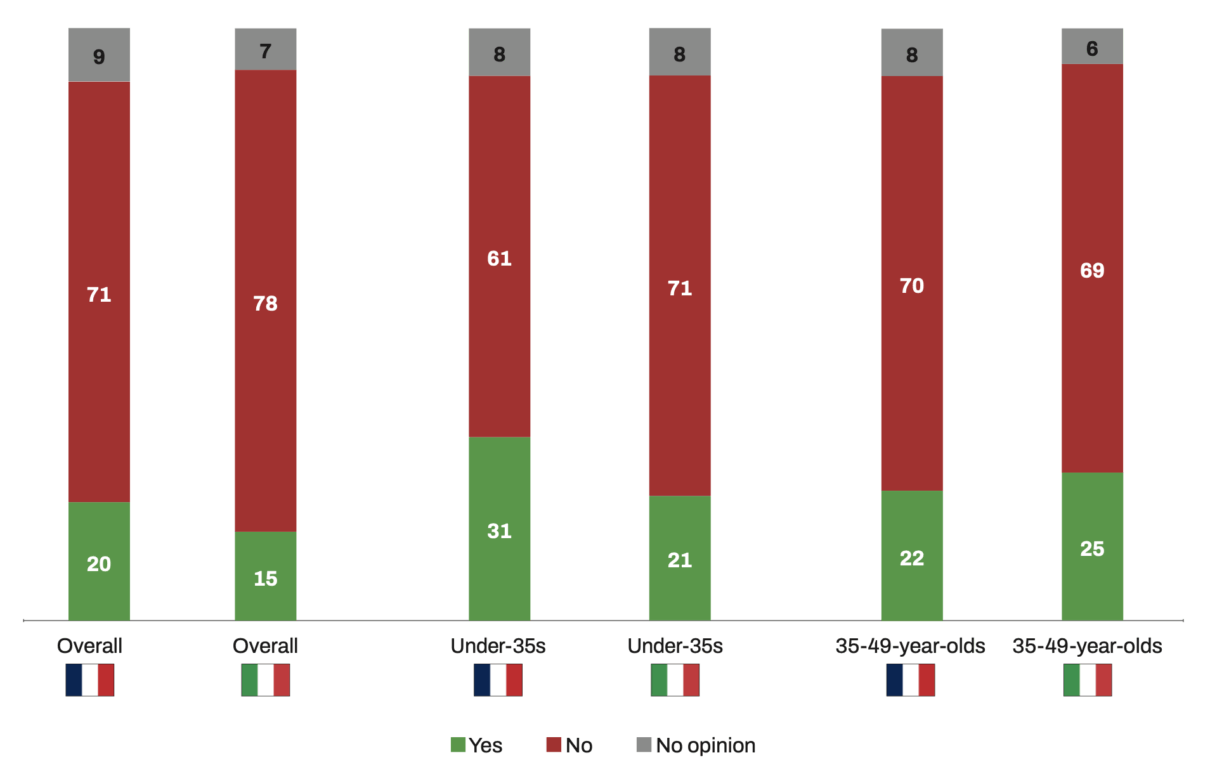

3. The idea that ‘having a child means jeopardising the future of the planet’ is shared by a minority of respondents (20%). While the under-35s are more likely to hold this view, it remains in the minority (31%).

4. A majority (59%) said they were concerned about falling birth rates. The over-50s are more concerned (63%) than the under-35s (57%).

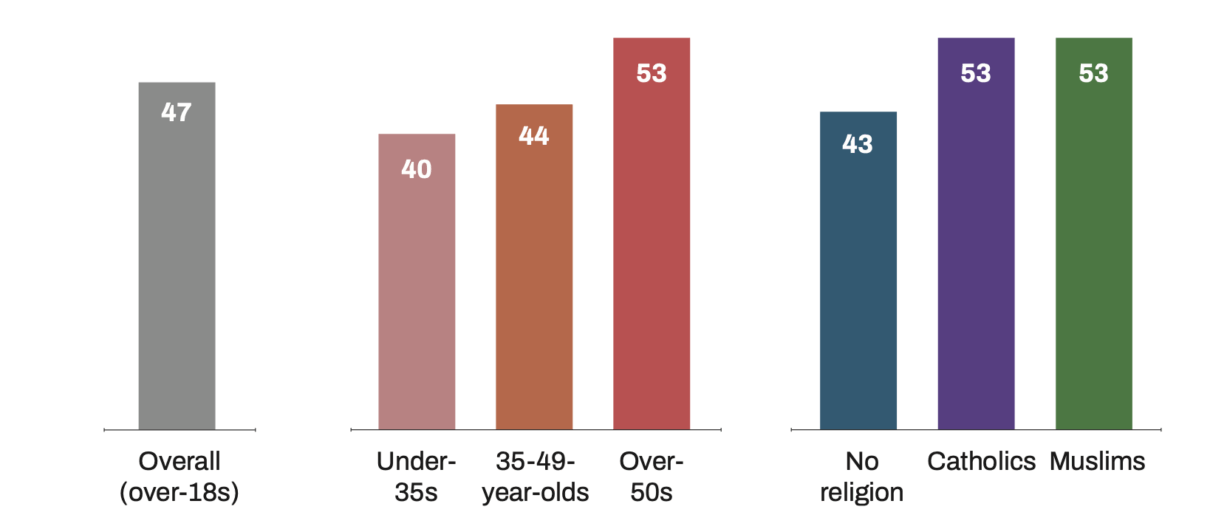

5. 40% of French people under 35 believe that the Government is ‘not concerned enough’ about falling birth rates. This view is shared by Catholics (43%) and Muslims (41%) of this age group.

6. Two-thirds (64%) of French people under 35 and 60% of those aged 35-49 are in favour of reducing income tax for couples with children to support their desire to have children.

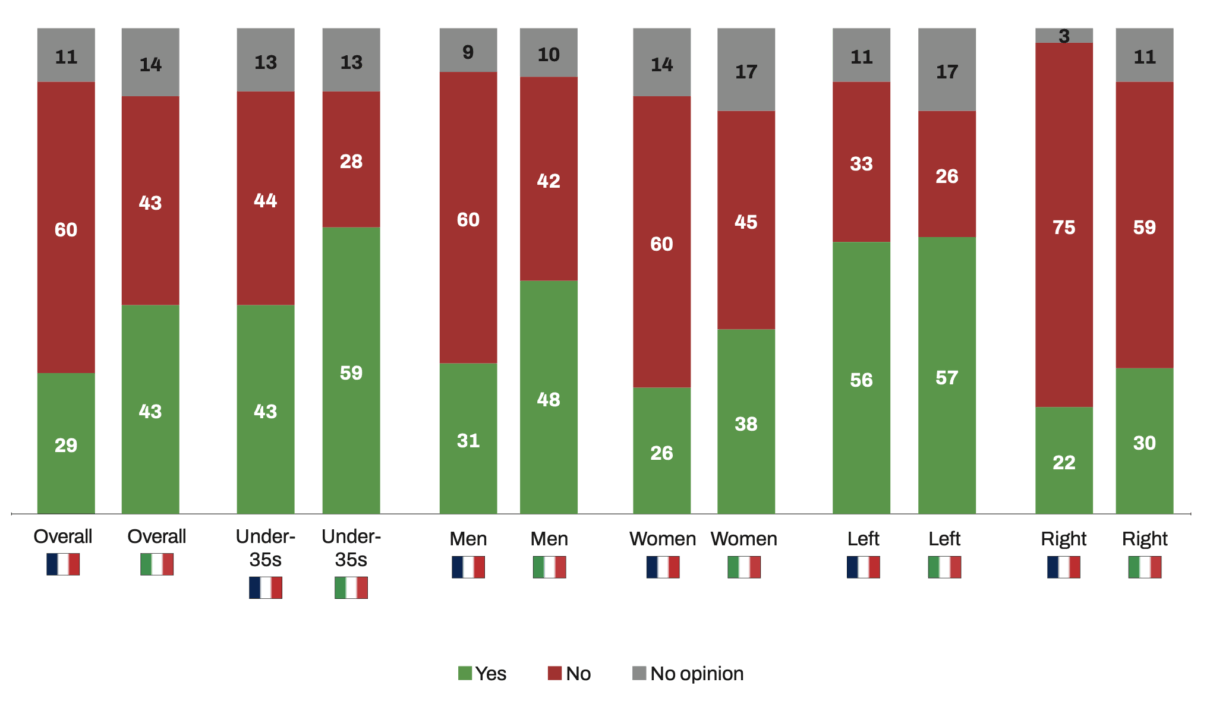

7. ‘Flexible working hours’ is considered the most effective measure to encourage births at company level (60%).

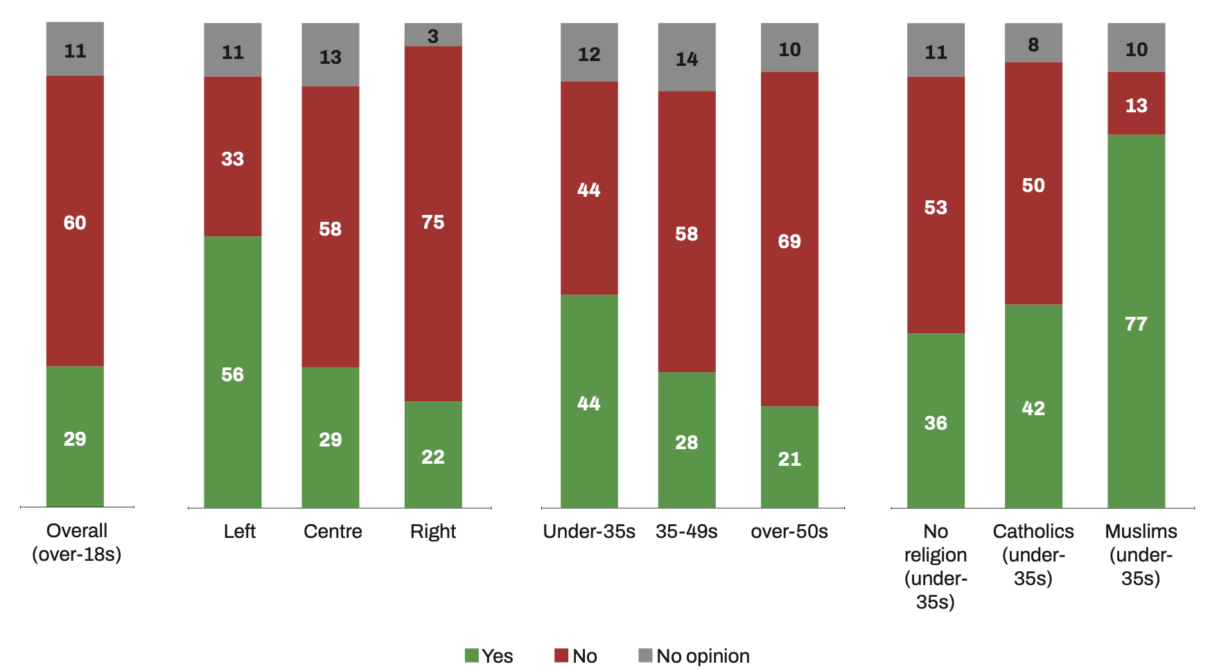

8. Immigration to ‘tackle falling birth rates’ is an option accepted by 29% of French people overall. The figure is higher among the under-35s (44%). Within this age group, the figure rises to 42% among Catholics and 77% among Muslims.

9. Left-wing respondents believe that immigration should be encouraged to tackle falling birth rates (56%), while those from the centre (29%) and the right (22%) believe the opposite.

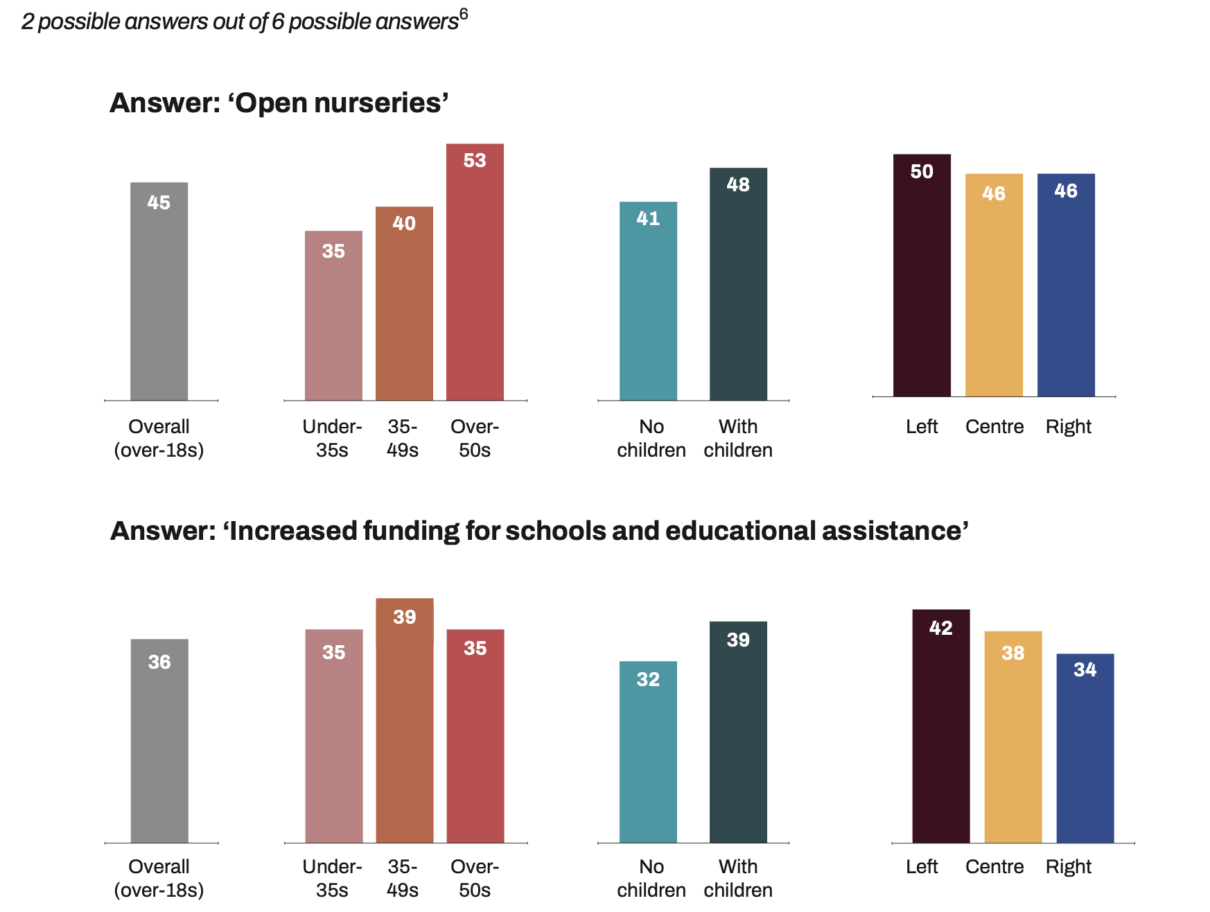

10. When the under-35s were given a list of measures to promote births, ‘opening nurseries’ (35%) and ‘increasing funding for schools and student aid’ (35%) came before ‘increasing family allowances’ (31%), ‘affordable housing programmes’ (24%) and ‘tax credits for childcare’ (18%).

11. Economic hardship is mentioned by only 14% of French respondents who have no children and do not wish to have any.

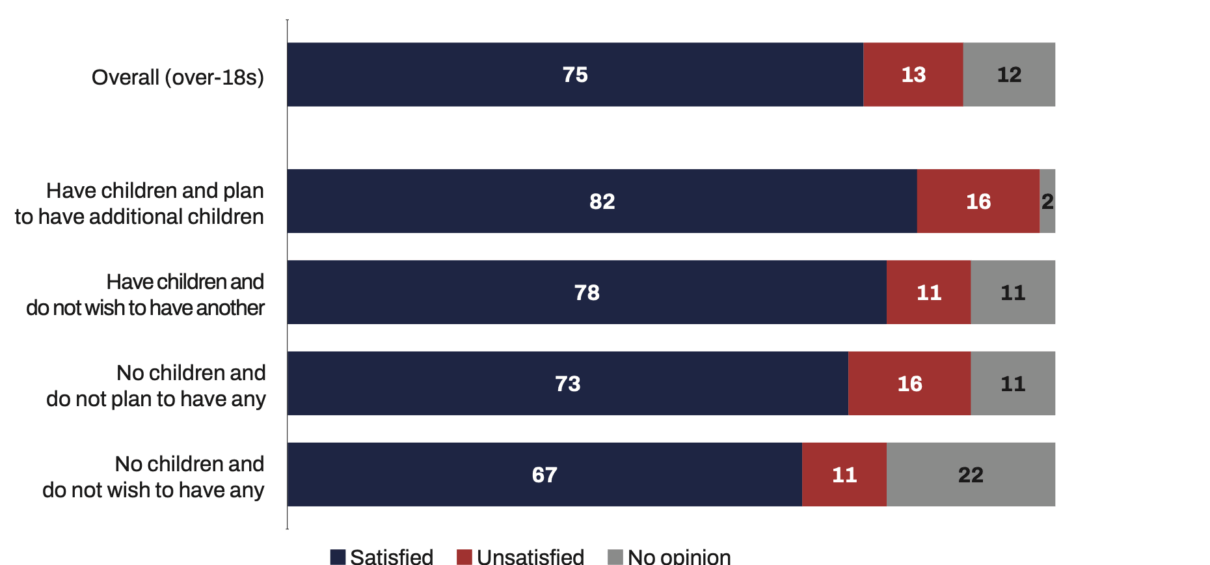

12. 75% of French people say they are satisfied with the way they reconcile their professional and family lives. This satisfaction is higher among the under-35s (78%) and parents (78%).

Findings for Italy

1. 75% of Italians under 35 who do not have children say they would like to have one or more and 79% of those who already have one or more children would like to have another one or more.

2. While on average 41% of atheists and respondents with no religion would like to have children, the figure is 43% among Catholics. In Italy, the religious factor seems to have less influence on the desire to have children. It is worth mentioning that around 80% of Italians identify themselves as Catholics. In France, 60% of the population is baptised or identify with a Catholic cultural identity, without always being practising Catholics or saying they are believers.

3. The idea that ‘having a child means jeopardising the future of the planet’ is shared by a minority of Italians (15%). While the under-35s are more likely to hold this view, it remains in the minority (21%).

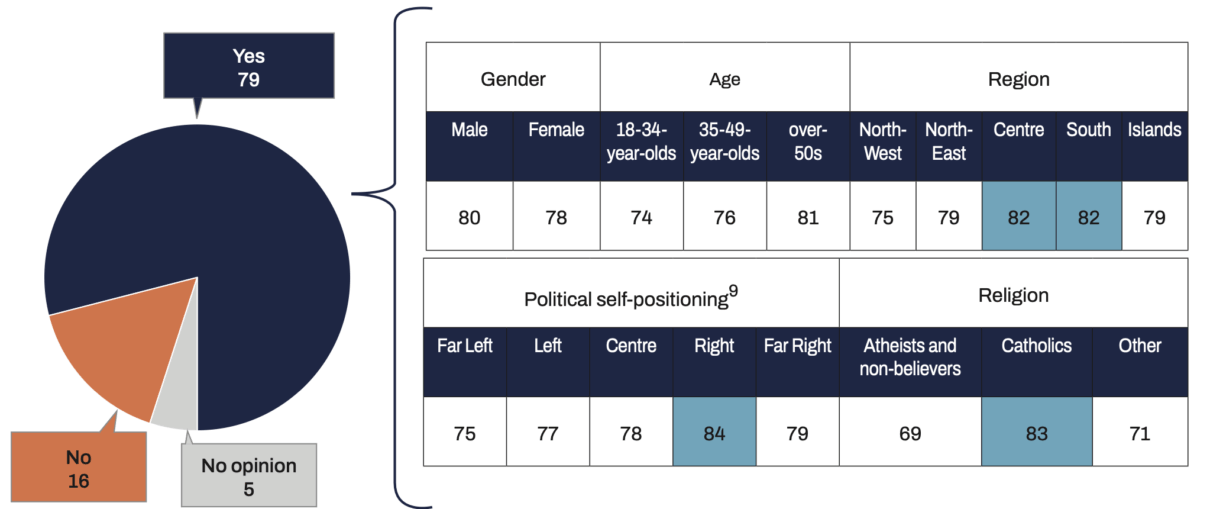

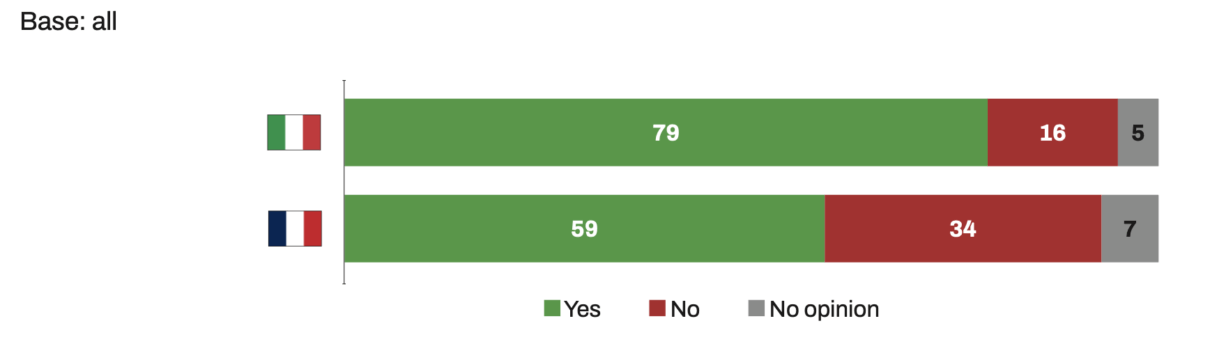

4. The vast majority (79%) of Italians surveyed said they were concerned about falling birth rates. The over-50s are more concerned (81%) than the under-35s (74%).

5. 37% of Italians under 35 believe that the Government is ‘not concerned enough’ about falling birth rates, compared with 54% of those aged 50 and over.

6. Almost three quarters (73%) of Italians under 35 and 72% of those aged 35-49 are in favour of reducing income tax for couples with children in order to encourage the desire to have children.

7. ‘Flexible working hours’ is considered the most effective measure to encourage births at company level (63%).

8. Immigration to ‘tackle falling birth rates’ is an option accepted by 43% of Italians. The figure is higher among the under-35s (59%).

9. In Italy, more left-wing supporters believe that immigration should be encouraged to tackle falling birth rates (57%) than centre (40%) and right-wing supporters (30%).

10. When Italians under 35 were given a list of the most useful measures for promoting births, ‘affordable housing programmes’ came first (56%), ahead of ‘increased family allowances’ (53%), ‘increased funding for schools and study aid’ (30%), ‘opening nurseries’ (24%) and ‘tax credit for childcare’ (9%).

11. Economic hardship is mentioned by 24% of Italian respondents who have no children and do not wish to have any.

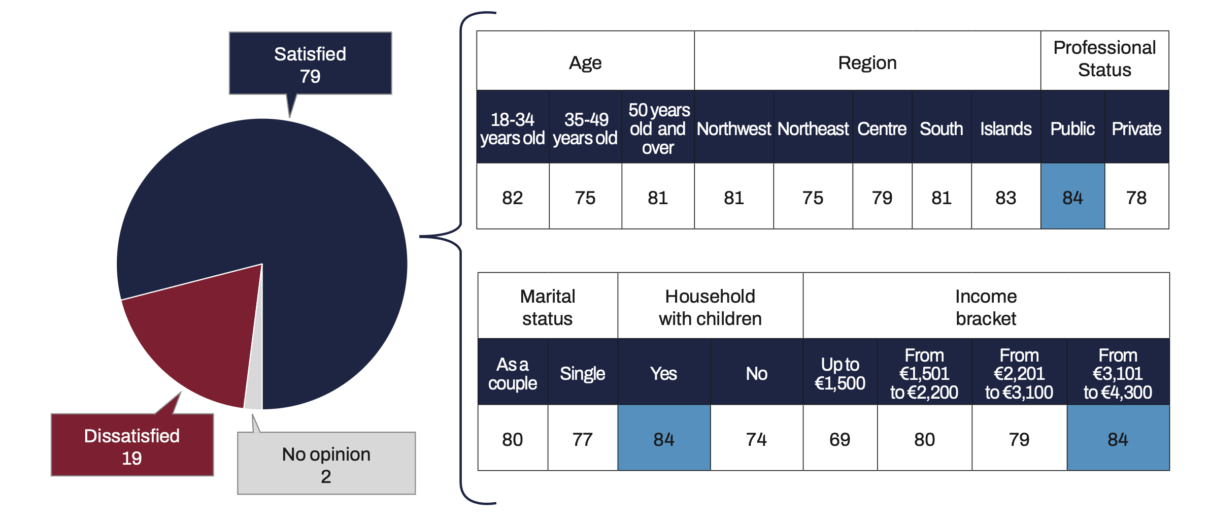

12. 79% of Italians say they are satisfied with the way they balance work and family life. This satisfaction is higher among those under 35 (82%) and those with children (84%).

In 2010, the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) (average number of children per woman of childbearing age) was 2.03 in France, compared with 1.44 in Italy. Today these rates have fallen to 1.62 and 1.18 respectively.1 The decline in the birth rate and the gradual ageing of the population now occupy a central place in public, economic and political debate. The implications of this phenomenon are far-reaching and transversal: they concern the sustainability of the pension and social protection system, the organisation of essential services – particularly in the fields of health and personal care assistance – as well as the structure of the labour market and the overall balance of public finances.

In 2025, the Fondazione Magna Carta in Italy and Fondapol in France launched a joint study on the birth rate, based on the opinions of citizens in both countries. The two surveys, conducted respectively by the Noto Sondaggi polling institute in Italy and the CSA polling institute in France, focus on four main themes: the desire for motherhood and fatherhood, reconciling work and family life, awareness of the demographic problem and initiatives to encourage births. These themes guide the comparative analysis, which is intended to be both quantitative and qualitative.

The French survey was conducted online between 15 and 23 January 2025 on a representative sample of 3,023 people. It was carried out using the quota method, taking into account gender, age, socio-

professional category and area of residence. The Italian survey was conducted online and by phone calls between 20 January and 3 February 2025 on a representative sample of 3,008 citizens. The criteria chosen were gender, age, geographical area and size of municipality of residence.

In both cases, scientific rigour and the precision of the data collection guarantee the reliability of the proposed analyses and their comparative validity. The aim of the survey is twofold: on the one hand, to measure the level of awareness of the demographic crisis and its consequences; on the other, to explore the desire for parenthood and the conditions – material, cultural, symbolic – that can hinder or, on the contrary, stimulate it.

The first part of this study analyses the case of France, where the fall in births, although real, does not seem to have affected the propensity to become a parent, particularly among young people, thanks in part to long-standing social protection policies and a more favourable public culture. The second part focuses on the situation in Italy, where the drop in the birth rate is more acute, and economic, professional and cultural constraints weigh more heavily on reproductive choices, generating uncertainty and renunciation. However, in Italy too, the desire to have children is mainly driven by young people under the age of 35. The third part offers a comparative analysis, highlighting the convergences and divergences between the two countries in terms of their experiences, expectations and expressed priorities, while offering suggestions for developing more effective and targeted public policies.

In both contexts, the birth rate is not just a statistical or programmatic challenge, but a genuine social and cultural issue. Putting parenthood back at the heart of public debate means reconnecting with a collective project based on continuity between generations, equity between territories and trust in the future.

The French are worried by falling birth rates but their desire to have children remains high, especially among the under-35s

The vast majority (70%) of young French people (under 35) who do not have children want them, and 75% of young people who already have children want to have another. or more.

While the number of births in France reached a new record low in 2023 (a 6.6% drop in births compared to 2022), the desire to have children remains very strong among French people under 35.

Among young people under 35 who do not have children (62% of respondents in this age group), 70% want to have children. This is more common among young Catholics (80%) than young Muslims (78%) or young people with no religious affiliation (64%). Among young people who are already parents, 75% want to have more children. However, this is more common among young Muslims (89%) than young Catholics (77%).

Desire for children by age and religious affiliation (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

This desire weakens significantly with age. Only 42% of 35-49-year-olds without children want to have children. And only 25% of parents aged 35-49 want to have more children.

The majority of French parents under 35 who do not wish to have any more children cite satisfaction with the number of children they already have (40%), a rate that rises to 57% in the 35-49 age group, as well as their desire not to have more children (33% in the under-35s and 43% in the 35-49 age group).

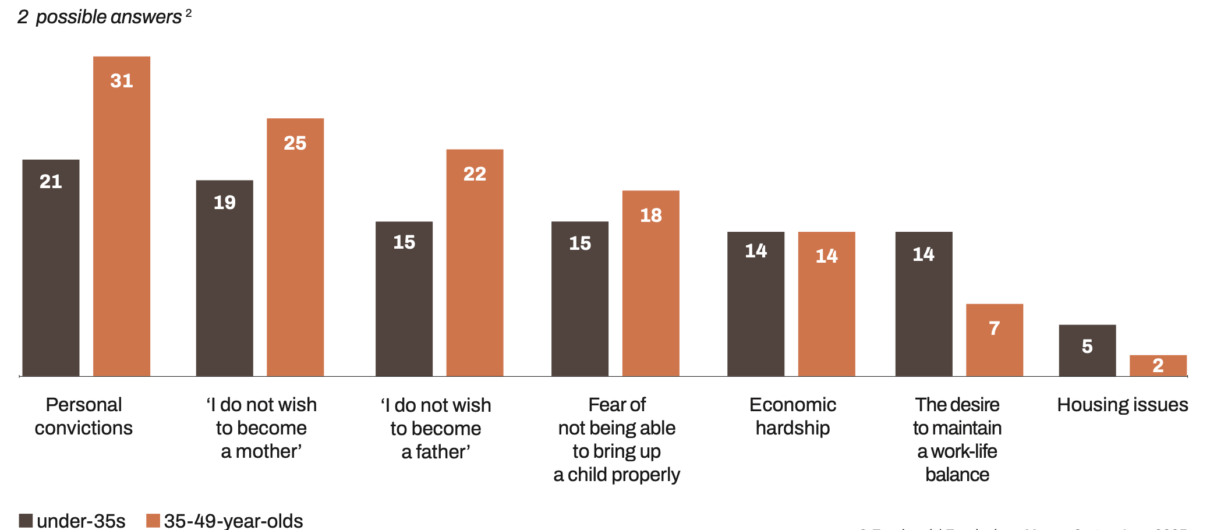

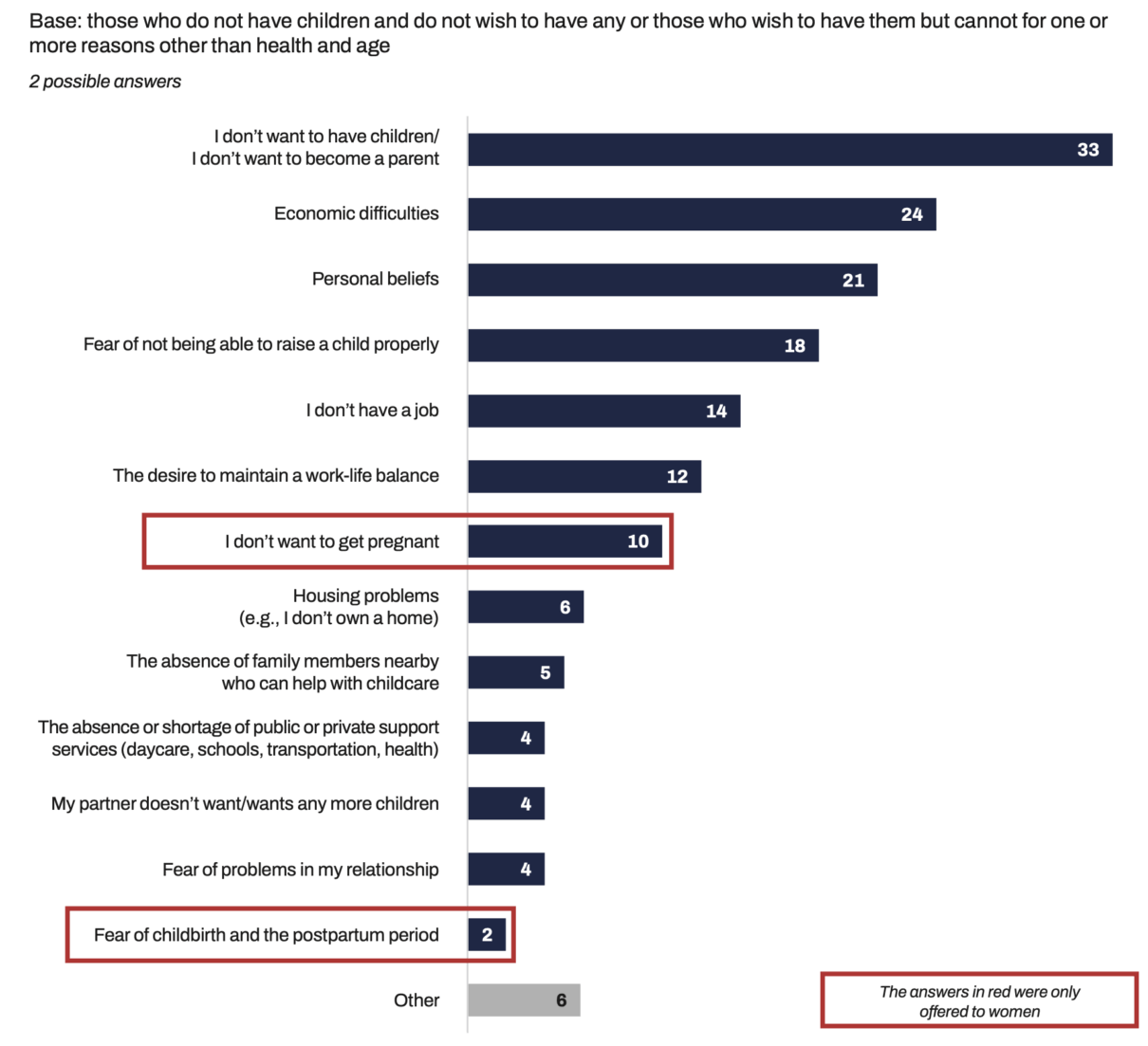

Meanwhile, French respondents aged under 35 who have no children and do not wish to have any often cite a decision linked to personal convictions (21%), ahead of the desire not to become parents (19% do not wish to become mothers and 15% do not wish to become fathers). 14% of young people who have no children and do not wish to have any state economic difficulties as an important factor. This figure is almost the same (16%) for young parents who do not wish to have additional children. These findings suggest that economic difficulties are one of the reasons for not/no longer wishing to have children, but that it is far from being the main reason. A notable feature in this age group is that 14% of under-35s without children and without the desire to become parents justify it by the desire to maintain their work-life balance.

The reasons given by the 35-49 year-olds without children differ slightly. 31% mention personal convictions, 25% do not wish to become mothers, 22% do not wish to become fathers, 18% fear not being able to bring up a child properly and 14% economic difficulties.

French people who are childless and do not wish to have children: what are the main reasons? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

The respondent had a choice of 14 possible answers to this question: Economic difficulties; I don’t have a job; Housing problems (e.g. I don’t own a house); The desire to maintain a balance between private and professional life; The absence of family members nearby who can help with child management; Fear of not being able to bring up a child properly; Fear of problems in my relationship; My partner doesn’t want children; I don’t want to get pregnant; Fear of childbirth and the post-partum period; Absence or shortage of public or private support services (crèches, schools, transport, health); Personal beliefs; I don’t want to have children/I don’t want to become a mother; I don’t want to have children/I don’t want to become a father.

There are also exogenous factors that can explain, in part, why people do not want or no longer want children. The perceived danger of today’s world seems to be a real brake on parenthood: 52% of French people believe that today’s world is too dangerous to have children. 60% of people from lower socio-professional backgrounds (CSP-), the under-35s (60%) and those who do not want to become parents (61%) are more likely to feel this way.

On the other hand, almost half (46%) of French people believe that falling birth rates could have harmful consequences for the country’s future. This view is widely shared by those aged 65 and over (62%), Muslims under 35 (56%) and parents, whether they want to have more children (58%) or not (51%). Only 25% of French people who have no children and do not wish to have any think that ‘not having children means risking the future of the country’.

‘To have a child is to jeopardise the future of the planet’ (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

No kids refers to those who, motivated by environmental concerns, personal convenience or pessimism about the future, choose not to have children.

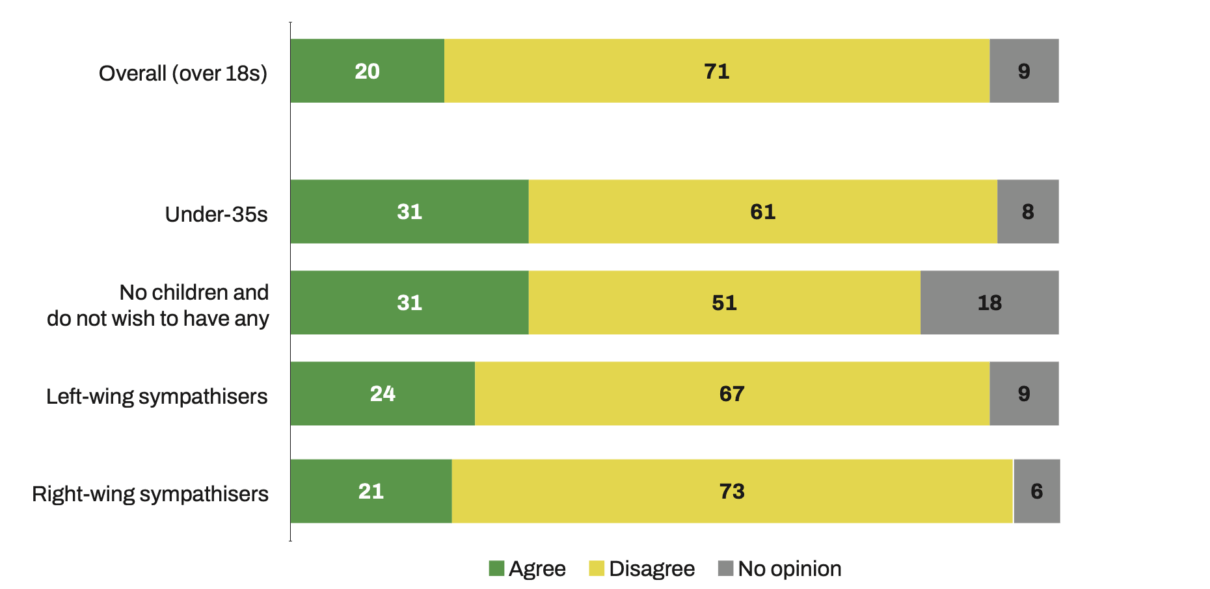

Finally, the argument linking eco-anxiety and parenthood receives relatively little support: only 20% say they believe that ‘having a child means jeopardising the future of the planet’. However, this figure rises to 31% among people aged under 35, 27% among executives and managers, 24% among left-wing supporters and 21% among right-wing supporters. Finally, it is also shared by 31% of people who have no children and do not wish to have any, 11 points more than the average French person, a sign of a certain penetration of these ideas among the No Kids3.

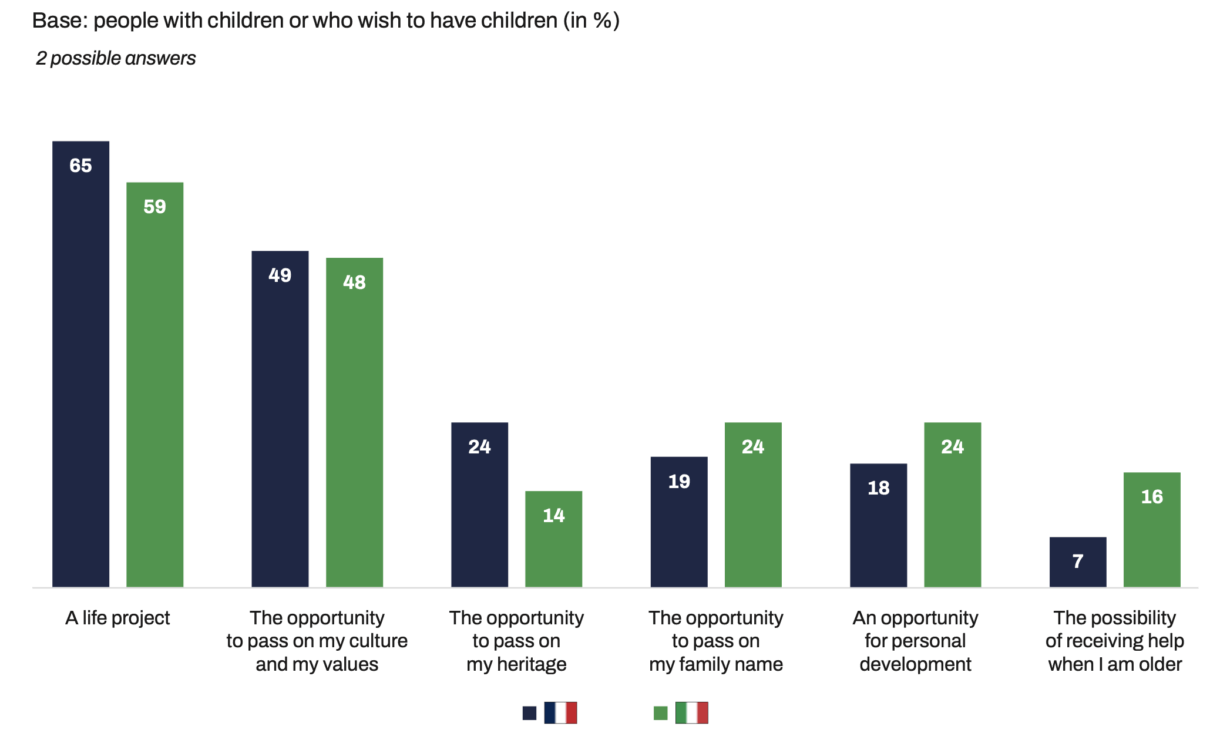

Having children is above all a ‘life project’ for 65% of them, particularly women (73%). This reason comes well ahead of the desire to pass on one’s culture and values (49% overall), which is put forward more by the over-65s (58%) than by the under-35s (46%). Other reasons are also given for having or wanting one or more children, but to a much lesser extent, such as the possibility of passing on one’s heritage (24%), which is more frequently put forward by people from lower socio-professional backgrounds (30%). The possibility of passing on one’s family name is mentioned by 19% of respondents, more than the 35-49 age group (18%). In addition, the opportunity for personal development was mentioned by 17% of both the under-35s and the 35-49s, and the possibility of receiving help in old age by 7%, more so among the under-35s (13%) than the 35-49s (6%).

Are you satisfied with the way you reconcile your professional and family lives? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

This point is particularly raised by the under-35s, 21% of Muslims compared to 12% of Catholics. More generally, the French are satisfied with their work-life balance (75%). This score rises among parents (78% for those who do not wish to have more children and 82% for those who want more children) but falls slightly among those who do not have children (73% for those who wish to have children; 67% for those who do not). Contrary to popular belief that the arrival of a child upsets the balance of life, this event is seen as rather positive and contributes to the personal well-being of the French. Finally, it should be noted that 82% of people in the highest socio-

professional categories (CSP+) are satisfied with their work-life balance.

On the other hand, the French expect more from society. They feel that society is not particularly supportive of parenthood: 42% of them feel that society does not encourage people enough to have children, especially those who have children and want to have more (53%), and Catholics (53%) and Muslims under 35 (47%). Those who have no children and do not wish to have any are more hesitant about society’s position on parenthood: 27% think society does not encourage parenthood enough, 23% think it encourages it enough and 21% think it encourages it too much, probably because they are less concerned about the subject.

Most French people (59%) are concerned about falling birth rates, including young people (57%) and 47% of French people think that the Government is not doing enough on this issue (30% think it is doing enough)

The fall in the number of births worries a majority of French people (59%), particularly those in the highest socio-professional categories (64%), those aged 65 and over (67%), Muslims (74%) and Catholics (65%). On the other hand, those who do not have children and do not want to have any stand out in terms of their views: half of respondents are not worried about this phenomenon (49%), which is fairly consistent with what was said earlier, namely that few of them also think that ‘not having children means risking the future of the country’.

Falling birth rates are a cause for concern, and the French feel that the Government is not taking this issue seriously enough. In fact, 47% of them feel that falling birth rates are an issue that the Government is not concerned about enough, a view held more strongly by those aged 50 and over (53%), Catholics and Muslims (53% each). Only 30% feel that the Government is doing enough, particularly the under-35s (35%), and 9% feel that it is doing too much. This feeling of a lack of support is a point of view particularly put forward by parents who no longer wish to have children (54%). Conversely, French people who do not have children and do not wish to have any more share the view that the Government is doing too much about falling birth rates (18% compared with 9% of French people overall).

‘The Government is not sufficiently concerned about falling birth rates’ (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

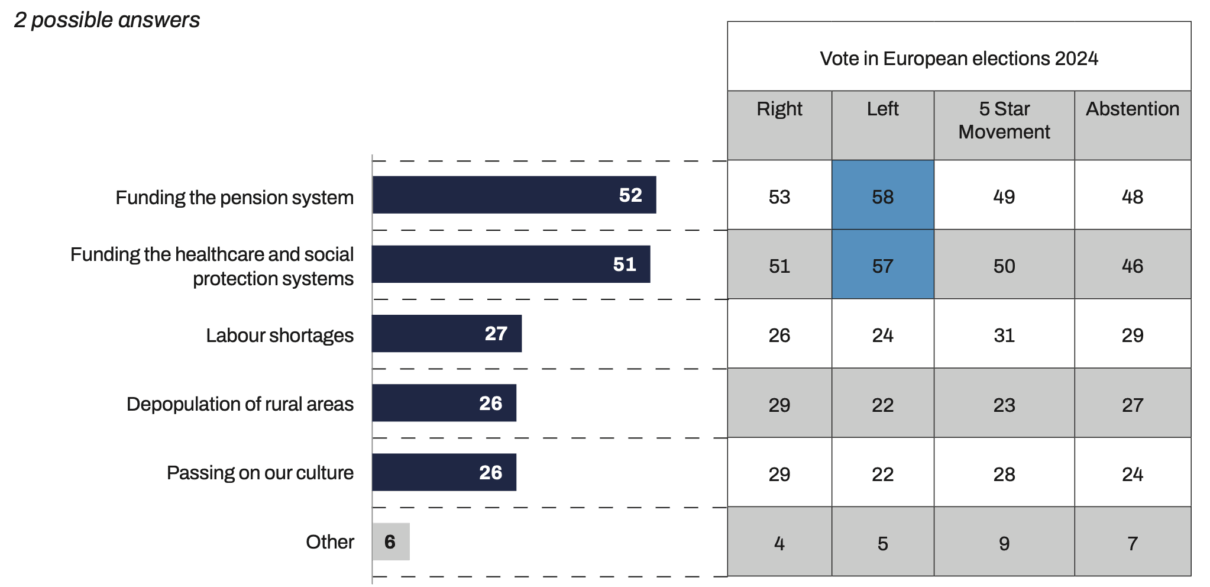

When French people are asked about the possible consequences of falling birth rates, they are mostly concerned about the challenge to fund the French social system: problems for the pension system (53%), a feeling more strongly shared by French people aged 50 and over (58%), and problems for the funding of the health and social protection system (49%), more strongly emphasised by French people aged 65 and over (56%) and left-wing sympathisers (58%). These two aspects are shared by all French people, whether they are parents or not. Other negative effects are also mentioned, but they appear fairly far down the hierarchy: problems with the transmission of culture (24%), particularly cited by the under-35s who are Muslim (32%) and Catholic (30%); depopulation of rural areas (24%), cited more often by French people living in towns with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants (27%); and labour shortages (19%). Parents who wish to have more children have a much more global view of the consequences of falling birth rates, and are far more likely to cite problems in passing on culture (34%), the depopulation of rural areas (31%) and labour shortages (28%), compared with 24%, 24% and 19% respectively for all French people aged 18 and over.

Popular measures to support births: tax credits, childcare services and flexible working hours

To counter the falling birth rate in France and its consequences (ageing population, labour shortages, jeopardising the pension system, etc.), a number of proposals were tested with the French.

Firstly, encouraging immigration met with strong opposition. Only 29% of French people were in favour, while 60% were opposed. Those most in favour are Muslims under the age of 35 (77%), left-

wing sympathisers (56%), French people under the age of 35 (44%), people with 5 or more years of higher education (39%), people living in the Greater Paris Metropolis (36%), executives and managers (36%) and parents who still want to have children (52%).

Conversely, those opposed to this solution (60%) are mainly right-wing sympathisers (75%), residents of towns with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants (70%), French people aged over 50 (69%) and parents who do not wish to have more children (69%).

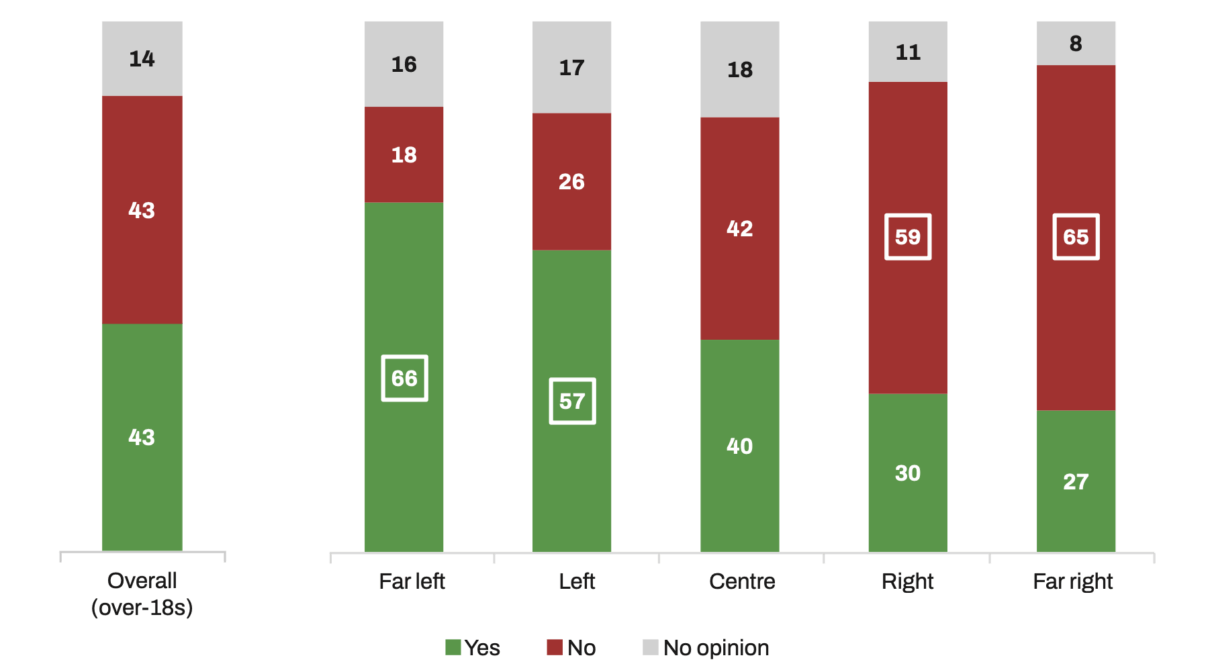

Should immigration be encouraged to tackle falling birth rates? (in %)4

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

The original question was “Would you be in favour of encouraging immigration to counter the falling birth rate?”.

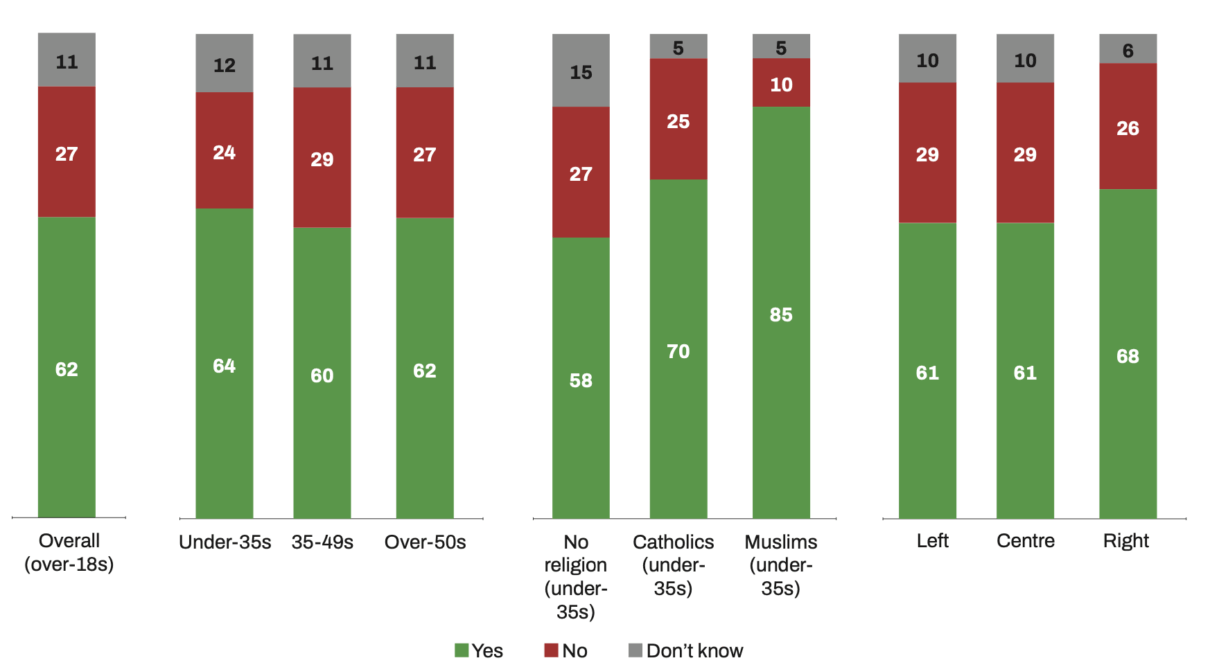

Secondly, French people are more in favour of reducing income tax for couples with one or more children, with around two-thirds (62%) in favour, particularly those who already have children (73% among those who wish to have more children and 66% among those who do not wish to have more children), as well as Muslims under 35 (85%), Catholics (70%), right-wing sympathisers (68%) and those living in the Greater Paris Metropolis (67%).

Should taxes be reduced for couples with children to promote births? (en %)5

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

The original question was: “To encourage births, should income tax be reduced/recalibrated for couples who have one or more children?”

Furthermore, many actions depending on public authorities are also perceived as useful in promoting births in France, with the opening of childcare facilities such as nurseries, as well as the increase in funding for schooling, cited respectively by 45% and 36% of French people, including those who do not (yet) have children. Those under 35 are less likely to highlight ‘the opening of nurseries’ (35%), but this measure remains the most chosen by this age group. Those aged 35-49 are the age group that most cites ‘increased funding for schools and student aid’ (39%). Left-wing sympathizers also cited these measures the most, with 50% and 42% of mentions respectively.

What measures should be taken to promote births in France? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

The original question was: “Which of these initiatives do you think would be most useful in promoting births in France?” Respondents had a choice of six possible answers to this question: More funding for home purchases; Opening of nurseries; Increased child benefits; Increased funding for schools and student aid; Tax relief for babysitters; Tax incentives for businesses offering birth-friendly services..

Other tax measures, however, seem to be less of a priority in the eyes of the French. 24% cite ‘increasing family allowances’ as a priority measure, a measure cited more often by those under 35 (31%). 24% also cite ‘affordable housing programmes’ (21% among those aged 35-49), 23% cite ‘tax incentives for companies offering services adapted to births’, with more people under 35 (26%) than those aged 35-49 (21%) promoting this measure. Finally, 18% emphasis on tax relief for employing babysitters, particularly among those who intend to have (more) children (23%).

Finally, companies also have a role to play in encouraging people to have children. Among the measures proposed, French people (60%) favour flexible working arrangements to encourage them to have children. Left-wing supporters were more likely to mention this point (68%). Extending paid maternity leave came in second place with 36% of mentions, also more frequently cited by left-wing supporters (45%). Remote work rounded out the top three, with 32% of mentions. It should be noted that financial support, highlighted by French people under 35 (29% compared to 24%), and longer paid paternity leave, mentioned more by left-wing supporters (31% compared to 25%) and working people (26%), seem to be incentives for future parents.

Conclusion

For many French people, having children is a life project and contributes to their personal well-being. If birth rates are to stop falling, the French are interested in a number of measures, and not all of them are financial: flexible working hours and organisation and easier access to childcare facilities for young children.

The demographic crisis in Italy: between thwarted desires and hope for the future

Unless otherwise stated, with regard to the desire to have children, the Italian part of the study surveyed the entire population (aged 18 and over).

The ‘demographic winter’ is defined by researchers as a ‘fatality’ or “inertia” whose effects are unlikely to change within a few years.

The issue of falling birth rates and the resulting ageing of the population is now at the heart of public, economic and political debate. The implications of this phenomenon are manifold and call into question the viability of the pension and social protection systems, the organisation of essential services – in the fields of health and social protection – as well as the structure of the labour market and the stability of public accounts.

The decision by the Fondazione Magna Carta and Fondapol to carry out a mirror survey in Italy and France is essentially intended to measure the level of awareness of the demographic crisis and its consequences, to offer food for thought in analysing how Italians and French people really perceive the seriousness of the demographic problem and their degree of awareness1. In conclusion, this survey makes it possible to envisage possible interventions in both the public and private sectors.

The analysis proposed below concerns the results of the survey carried out on the Italian sample and is organised as an argumentative threat. It covers both the total sample and the sub-group of childbearing age (18-49), with the aim of providing an overview that incorporates the broader socio-cultural dimensions and the operational dimensions relating to the parental choices that can actually be made. The present study sought to highlight the most relevant points that can, in the immediate and long term, help to reverse the demographic decline.

After a brief overview of the demographic situation in Italy, this analysis looks at the degree to which Italians are aware of the demographic issue and then assesses the relevance and effectiveness of concrete actions to stimulate births.

In the second part, the analysis focuses on personal responses to the choice of having children, paying particular attention to a very intimate aspect: the desire to become parents, a central element in any consideration on demographic policies.

The third part deals with reconciling work and family life. On this point, the survey provides rich and, in some cases, surprising answers, particularly with regard to the role that companies can and should play in supporting parenthood.

The fourth and final part of the survey examines the proportion of the sample who already have children or who would like to have children. The motivations provided by the respondents may then represent a favourable starting point for building more effective public policies capable of countering the ‘demographic winter’2.

Summary of the demographic situation in Italy

Ibid.

OECD and European Union, ‘Health at a Glance: Europe 2022 State of Health in the EU Cycle’, OECD Publishing, 5 December 2022 [online].

OECD and European Commission, “Health at a Glance: Europe 2024: State of Health in the EU Cycle”, OECD Publishing, 18 November 2024 [online].

Italy recorded 370,000 new births in 2024, around 10,000 fewer than in 2023 (-2.6%)3. Between 2008 and 2024, births fell by around 200,000, making Italy the only one of the twenty-seven countries in the European Union where there has been a steady decline in births every year since 2008.

The demographic decline of recent years led to a historically low total fertility rate (TFR) of 1.18 children per woman in 2024, below the value recorded in 1995 (1.19). It is attributable both to the decline in the number of women of childbearing age (15-49) and to a later age of childbirth (32.6), leading to a gradual fall in the total fertility rate. At the same time, thanks to advances in science and medicine, life expectancy is rising steadily: according to data from ISTAT 2024, men in Italy live on average 81.4 years, and women 85.5 years44. While this figure represents an important milestone in terms of public health, it is combined with a sharp increase in chronic diseases: around 40% of the Italian population suffers from at least one chronic disease, a percentage that rises to 70% among the over-65s5.

In addition, Italy faces a growing demand for care and assistance services due to an ageing population: only 10% of the over-75s currently benefit from adequate home support, while spending on ‘long-term care’ is expected to double by 2070.6

The ageing of the population, a reflection of the demographic crisis, is a particularly marked phenomenon in Italy, where the average age has reached 46.4 and the over-65s now account for 24% of the population.7 This dynamic raises serious questions about the sustainability of the social protection system, particularly in the pension, health, school and higher education sectors, and also generates difficulties in terms of employment policies and the generational transmission of values, experience and skills.

As a result, Italy has one of the highest levels of public spending on pensions in Europe, reaching 16% of GDP8. This economic burden risks becoming even heavier if it is not accompanied by structural reforms and demographic rebalancing measures.

In the light of this scenario, it seems difficult to foresee a reversal of the trend in the short term. According to the research Per una primavera demografica (For a demographic spring), carried out in 2024 by the Fondazione Magna Carta, the decisions taken today in demographic matters will inevitably have a decisive impact in the decades to come.

a. The ‘demographic issue’: the Italians between awareness and doubt

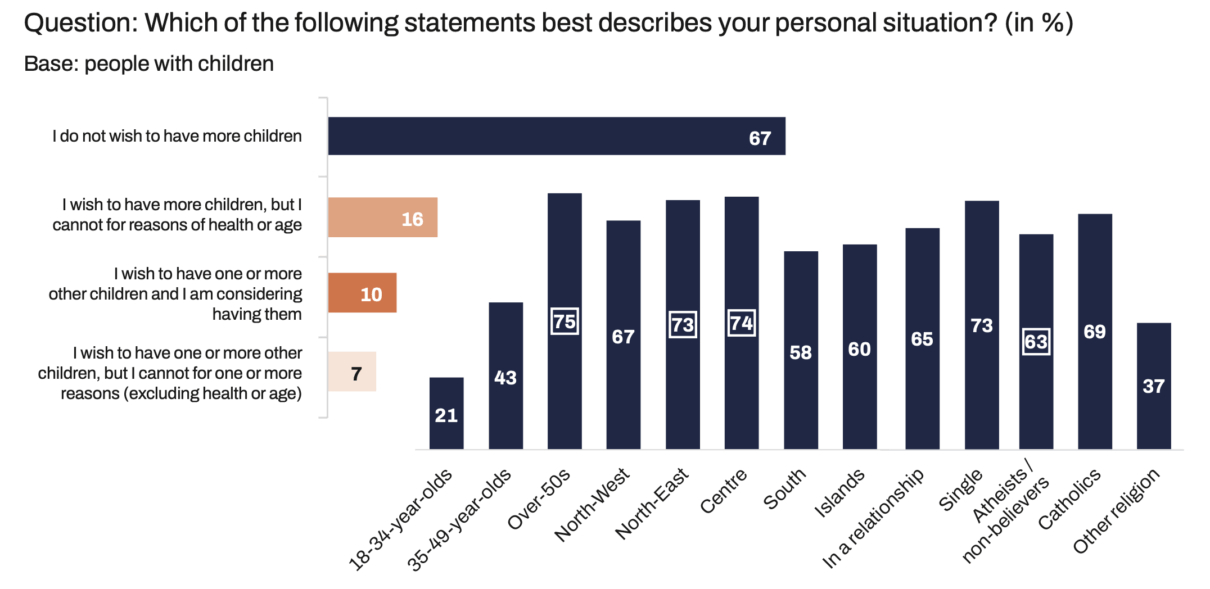

To what extent are the Italians aware of the importance of the demographic issue? The first answer seems fairly clear. The survey shows that 79% of respondents consider the falling birth rate to be ‘worrying’. This figure is even higher among right-wing sympathisers (84%) and Catholics (83%).

In 2023, the number of births in Italy reached a new record low.

Do you think the fall in the number of births in Italy is a cause for concern? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

In the Italian questionnaire, the term centre-right was used. In Italy, this term refers to the parties in the ruling coalition: Forza Italia, Fratelli d’Italia and the Northern League. We have chosen to use “right” instead of “centre-right” in English. Similarly, the term centre-

left was used. In Italy, this term refers exclusively to the Democratic Party. We have chosen to use ‘left’ instead of ‘centre-left’ to describe these voters.

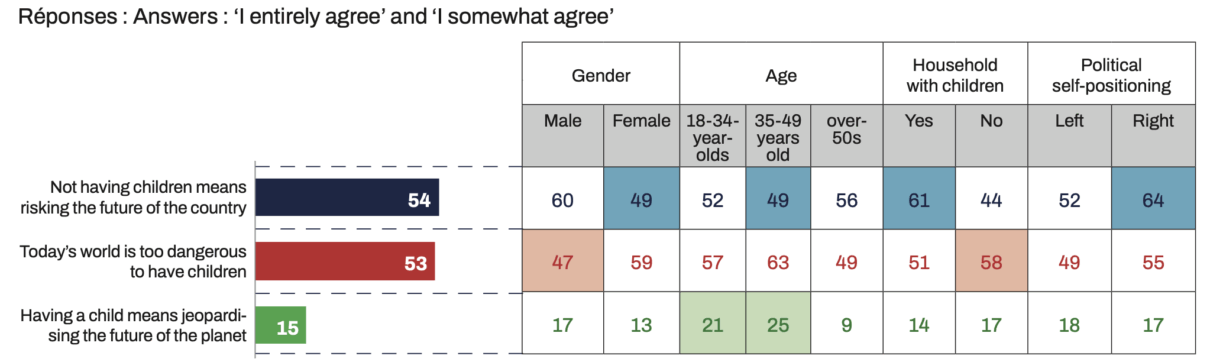

However, if we look in more detail, public opinion seems highly divided between those who believe that ‘not having children means risking the future of the country’ (54%), particularly mentioned by men, and those who express the fear that ‘today’s world is too dangerous to have children’ (53%). Uncertainty inherited from the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical instability, the energy crisis, the fear of an escalation of armed conflicts and the difficult economic situation may have heightened this general anxiety about the future.

Do you agree with the following statements ? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

A large number of respondents identified the most serious consequences of falling birth rates in the difficulty of maintaining the pension system (52%) and the sustainability of the health and social protection system (51%). Those who voted for left-wing parties at the 2024 European elections were even more likely to raise concerns for the sustainability of the pension system (58%) and the health system (57%).

Which issues do you consider to be the most significant in the context of declining birth rates? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – juin 2025

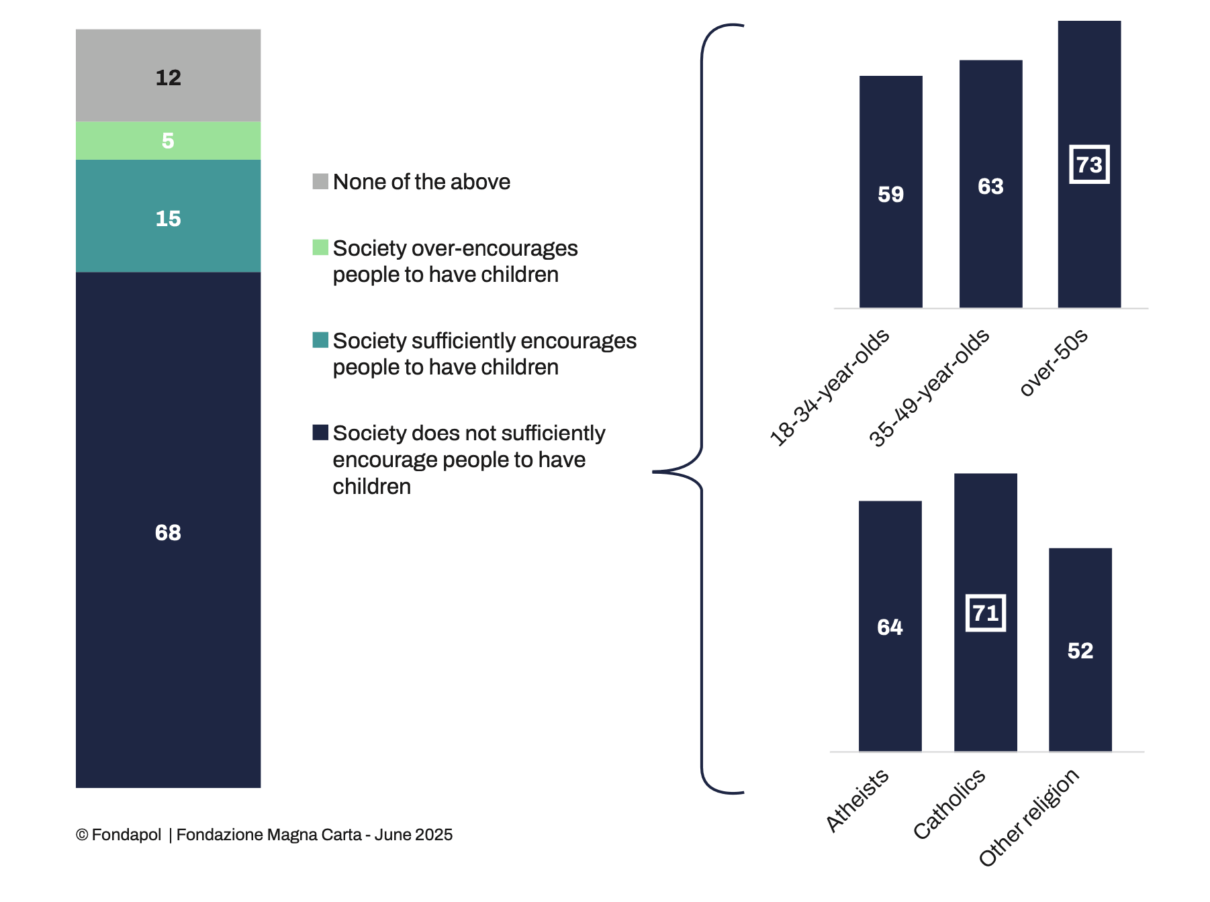

An overwhelming majority (68%) – with even higher figures among right-wing sympathisers (70%) and Catholics (71%) – believe that the way society is currently organised does not encourage people to have children. This should be a wake-up call for institutions at all levels, from the education system to the work place.

Which of the following statements do you most agree with? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

Almost half the sample (48%) would like to see a stronger commitment from the Government on family policies, with higher percentages among those with more than two children (56%), among left-wing voters (53%) and among citizens who did not vote in the 2024 European elections (57%). This last figure suggests that greater institutional attention to demographic issues could also have a significant impact on voting turnout and future electoral dynamics.

In any case, if we aggregate the answers of those who feel that the Government is concerned ‘enough’ (37%) and ‘too much’ (15%) about falling birth rates, it exceeds the majority (52%). Right-wing voters seem espeically satisfied with the current executive’s family policies (62%). These figures – the highest aggregate figures among the categories of respondents – also demonstrate a greater sensitivity to measures to promote birth rates and families.

However, it should be noted that 38% of this electorate believe that the Government’s commitment should be even greater, indicating that expectations on this cross-cutting issue are high and widespread.

b. From awareness to possible solutions

While a majority of Italians are aware of the demographic crisis and its effects on the social system, they differ on the solutions to adopt to reverse this demographic trend.

In this regard, immigration appears to be a divisive policy : left-wing sympathisers were more in favour of immigration to counter the effects of falling birth rates (57%), whereas right-wing sympathisers were mostly opposed to this option (59%). Meanwhile, centrists are almost equally divided between those in favour and those against.

Would you be in favour of encouraging immigration to tackle falling birth rates? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

Fondazione Magna Carta, Per una Primavera demografica, 2024, p. 120.

As a matter of fact and regardless of political orientations, immigration has had and continues to have a significant impact on demographic dynamics, especially in countries that have adopted more structured reception policies. This aspect was highlighted in our study Per una primavera demografica (For a demographic spring), which looked at the cases of Germany, France and Sweden, where immigration has partially offset the drop in births within the local population.10

However, in most cases, the fertility rate of immigrant women tends to fall over time, as they integrate into the social dynamic of the host country. Italy is no exception to this and a broader reflection is needed on the effectiveness and limits of migration policies as a structural response to demographic decline.

Fiscal and social measures receive a broader support than immigration. In particular, income tax reductions and recalibrations according to the number of children is almost unanimously (77%) considered to be an effective proposal for encouraging the births. Support for this proposal reaches 82% among those who already have children and 83% among those with a monthly income of over €2,201.

Among the initiatives considered most useful for stimulating births, Italian citizens rank first an increase in family allowances (51%) and making it easier to buy a first home (39%), followed by increasing the number of nurseries (33%), which are recognised as fundamental tools for supporting families.

The issue of housing requires further consideration. The survey reveals that the majority of respondents already own their home. However, the under-35s overall expressed a strong need for support in buying their first home, which they see as a fundamental condition to start a family. Indeed, 56% of young people believe that access to housing is one of the most effective solutions for encouraging births. However, a clear territorial difference emerges between the North and the South. Whilst the population from the South shows a clear preference for social benefits, such as increased family allowances (57% compared to a national average of 51%), people in the North-West call for more and better-quality public services such as nurseries and childcare facilities (38% compared to a national average of 33%). In this context, the 5 Star Movement seems more effective in responding to demands from the South, where there is greater demands for direct economic aid.

Motherhood and fatherhood: between desire and fear

The analysis covers both the total sample and the subgroup of childbearing age (18-49), with the aim of providing an overview that integrates broader sociocultural dimensions and operational dimensions related to the parental choices that can actually be made.

Having analysed awareness of the demographic crisis and the possible solutions to be adopted, we now look at a more intimate and subjective dimension: that of personal choices. Here the data takes on a different but equally significant tone and reveal the underlying phenomena already described in previous sections.11

The desire to have children (general population)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

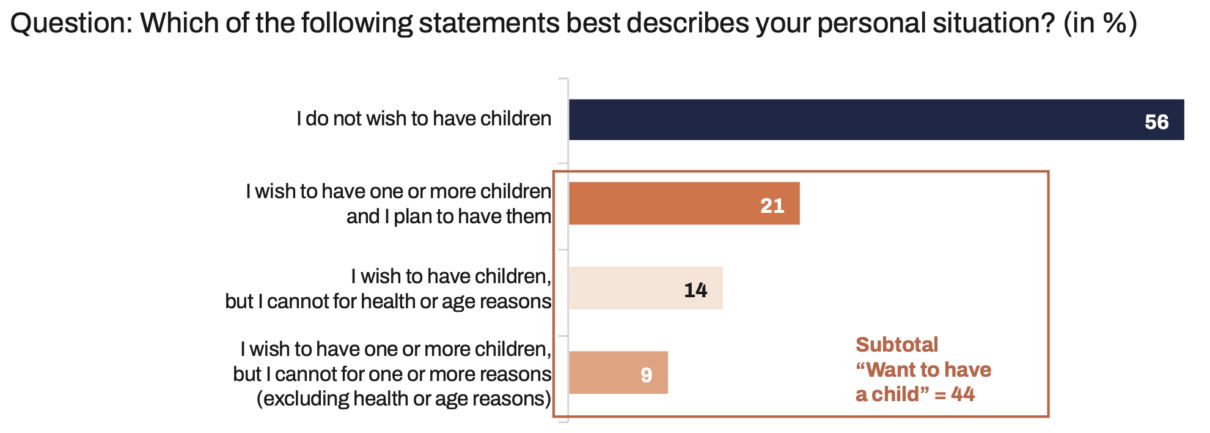

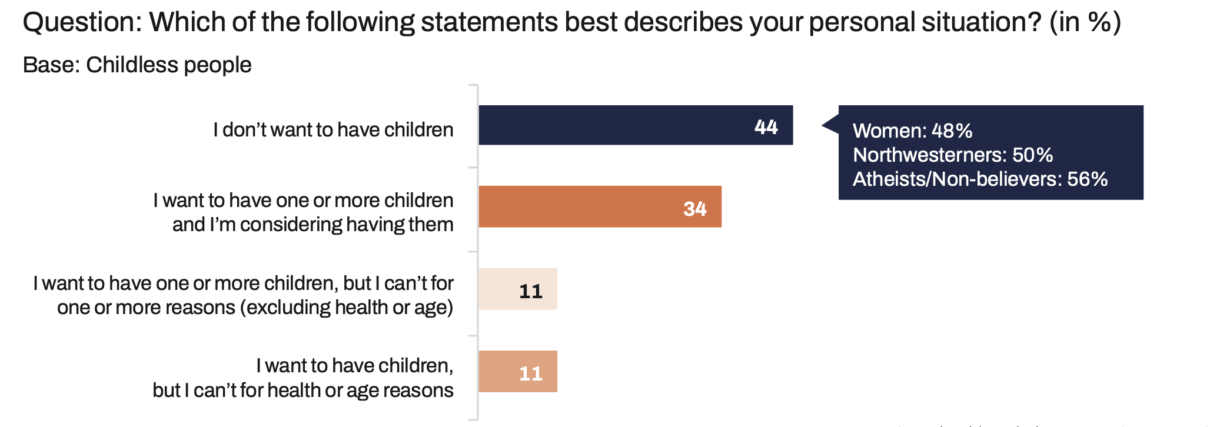

Our study reveals that 56% of Italians say they do not want children. But one should take this figure with caution, for it refers to all respondents and therefore includes both those who are already parents, those who have no children and those over-aged. If we analyse the sub-categories, we see that the percentage rises to 67% among those who already have children and have no intention of having more, while it falls to 44% among those who have no children. The latter percentage is nonetheless significant, but less ‘shocking’, considering that 34% of those who have no children say they intend to have them in the future and 11% express the desire to become parents but are unable for one or more reasons other than health or age problems.

Taking these last two responses together, the percentage of those who want or would like children (45%) is one point higher than that of those who do not (44%). A sign, then, that the desire is not dormant. Among those who do not have children, those who want a child are mainly the under-35s (48%, nearly 60%) and those living in central Italy (43%) and the islands (Sicily and Sardinia). The South, on the other hand, is slightly above the national average (36% compared with 34% nationally). The percentage rises in the lower middle income bracket (1,501-2,200 euros), reaching 43%, and, albeit only slightly, among Catholics (36%).

The desire to have children among childless people

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

The desire to have more children among people with children

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

If we only consider the population of childbearing age (18-49), the data is clearer. 50% of those who do not have children say they want or plan to start a family, compared with 31% who say they have no intention of bringing a child into the world. Respondents in central Italy (62%) and Catholics (56%) are more likely than the general population to want children (50%), while this is the case for a minority of respondents in the North-East (40%). The situation is more nuanced among the 18-49-year olds who already have children,: 36% say they would like to have another child or more, while 37% are satisfied with their current number. Within this group, a significant proportion (22%) would like to have children but say they are unable to for reasons other than health or age. This proportion is particularly high in the South (34%) and among people on low incomes (48%).

However, those who do not have children and do not want them are mainly from the North-West (50%), the Centre (33%) or the South (39%). In addition, the percentage rises among people on modest incomes (49%) and among non-believers (56%). In addition, respondents in the South cited economic difficulties more frequently than those in the North as the main reason for giving up parenthood. The difference between the sexes is also significant: among those who have no children, women (48%) are more likely than men (39%) to say they do not want any. This trend is also confirmed for those who already have children and plan to have more (33% for women versus 34% for men). This result is particularly surprising, for it challenges conclusions drawn from numerous surveys that had shown a significant stability in the desire for motherhood, despite significant challenges. Although it is not possible to compare different studies directly, this survey unequivocally indicates a trend that requires further reflection: women’s desire to have children now seems less obvious and more conditioned by external factors.

One of these factors is certainly the fear of losing one’s job. According to the latest INPS report, in the year following the birth of their first child, mothers are around 18% more likely to leave their job in the private sector than in the years preceding maternity. In practice, this translates into around 11% of women actually losing their jobs in the year following childbirth12. It is as if, over the generations, the fear of having one’s life turned upside down by the arrival of a child has gradually taken hold – even unconsciously – despite the regulatory, social and economic progress made in recent decades. In many cases, this fear translates into a refusal to have children.

However, if we look in detail at the individual motivations of those who do not have children, the most widespread remains that of ‘not wanting children’ (33%), followed by economic difficulties (24%), personal convictions (21%), fear of not being able to bring up a child properly (18%), being jobless (14%), maintaining one’s work-life balance (12%), and finally fear of childbirth and the post-partum period (2%). This alternation between ‘objective’ motivations (economic, social, professional) and ‘subjective’ motivations (linked to the individual’s perception of his or her role in the world) is indicative of a society in which, for many, a life without children seems easier or less risky.

You’ve decided not to have children

What is or are the main reason(s) for this choice? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

53% of respondents believe that ‘today’s world is too dangerous to have children’. 15%, on the other hand, respond that ‘having a child means endangering the future of the planet’, a percentage that rises to 21% among 18-34 year olds and 25% among 35-49 year olds, a sign of a growing, albeit minority, belief that the environmental emergency is linked to overpopulation.

The desire for motherhood and fatherhood appears to be driven by the under-35s: almost 60% of them want to have children, a figure which falls to 48% for those who already have children, although this is still higher than the average. These last elements confirm our previous remarks. Affordable housing makes it possible to start a family and reinforces the widespread desire of young people to become parents, a desire that gradually weakens when they come up against everyday reality. Indeed, the lack or inadequacy of services such as nurseries, holidays, support for parenthood is a recurrent reason given by parents who are giving up on having more children and comes up third in the reasons given (18%). With experience, parents become aware of the difficulties and often opt for a single child.

Fear is a recurring factor. Among those who do not wish to become parents, one in four expresses fears linked to their own ability to bring up a child properly, the possibility of negative effects on the couple’s stability or, in the case of women, fear of childbirth. This aggregate slightly exceeds the figure of those who cite economic difficulties as the main reason for their choice (24%).

A similar trend is found among people who already have children: in this group too, fear is mentioned by more than 25% of respondents, a proportion equivalent to that of those who cite economic difficulties. These two reasons come after ‘satisfaction with the number of children already present’ (37%), the most frequently cited reason, Fear is therefore not a secondary factor: it is one of the common threads running through parental choices. It represents one of the interpretative strands of the motivations expressed, accompanying and amplifying their deeper meaning. So much so that we also find the dimension of fear in the data already discussed above.13

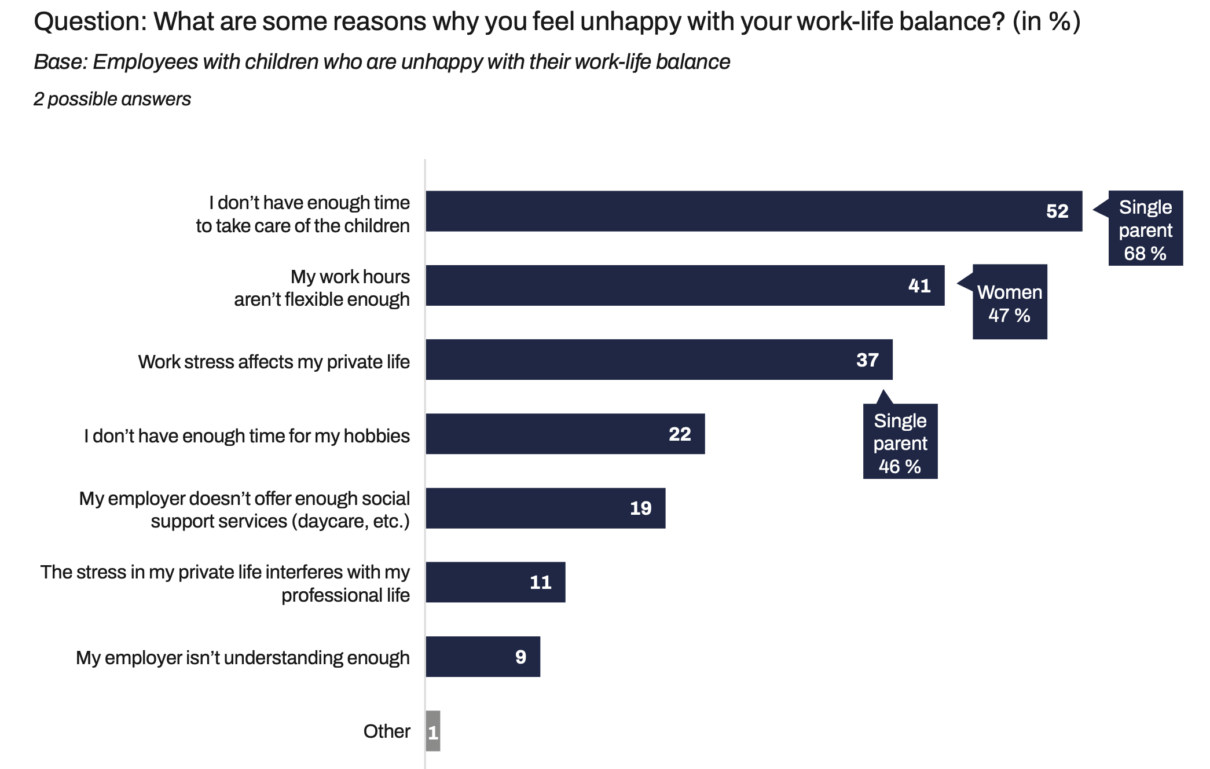

Work-life balance : how to reconcile work with parenthood?

The survey also explores the crucial issue of balancing work and family life, an increasingly central dimension in thinking about birth rates and quality of life. Across the entire sample of employees, both those with children and those without, there was a high degree of general satisfaction: 79% of those surveyed said they were satisfied with their work-life balance, a percentage that even exceeded 80% among parents. At first glance, this figure may seem surprising, but it can be explained by the fact that it refers to subjective perceptions of personal balance, and not necessarily objective working conditions.

Are you satisfied with the way you manage to balance your work and family life? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

However, a closer analysis of employment dynamics reveals significant differences between socio-professional categories, between those with higher incomes and those with more limited economic resources, between public and private sector employees, and above all, between men and women. Women seem to be more exposed to the difficulties of day-to-day management, which hinder their efforts to reconcile work and family life. It is no coincidence, as the survey shows, that men are more likely than women to say that their partner manages to spend more time with their children (37% versus 21%). These figures reflect the persistent imbalance in the distribution of family responsibilities, with a significant drop in the 18-34 age group, where only 19% say that their partner is able to spend more time with their children, compared with an average of 29%. This suggests that the professional difficulties encountered by younger people have a greater impact on family balance.

In general, the people who express the highest levels of satisfaction are those with average to high incomes and who work mainly in the public sector, where there are often greater possibilities for organising working hours and more stable contractual guarantees.

Satisfaction with work-life balance varies significantly between the North and the South, but also according to the size of the municipality in which people live. While the majority of those surveyed acknowledged that flexible working hours were the main factor in achieving a good work-life balance (47%), networks of family and friends constitute a fundamental support in day-to-day management in southern Italy reaching 52% compared to a national average of 44%. This figure rises even higher in small municipalities with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants, where the presence and importance of local networks is even more marked.

On the other hand, it is in the North-East that support from family networks is the lowest (38%). The percentage of partners able to devote time to their children is the lowest (18%) there too but the use of company social services is the highest (11% compared with a national average of 5%). This trend is particularly marked in medium-sized municipalities (between 10,001 and 30,000 inhabitants), where the presence of organised services plays a more important role than informal family help. The percentage in these municipalities is 14%, 3 points higher than the overall average for the North-East.

People dissatisfied with the way they reconcile their work and family life often cite lack of time to devote to their family as the main reason (52%). This figure rises even higher among women (54%), residents of the North-East (64%) and in towns with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants (71%). Next comes the inadequacy of working hours, cited by 41% of respondents, in particular women (47%), working people aged between 35 and 49 (49%), particularly those working in the private sector (42%), and residents of small towns (62%), reaching a peak of 86% in towns with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants in central Italy.

For those living in this context, organisational rigidity is particularly burdensome due to the lack of complementary services, and translates directly into a reduction in the time available to devote to the family. Added to this is the need, for many, to make fairly long commutes to work, not so much because of the distance in kilometres but because of the inefficiency of the infrastructure and road links. It is no coincidence that work-related stress, which affects personal life – the third cause of dissatisfaction, reported by 37% of the sample – registers significant peaks: it reaches 50% among civil servants and 46% in the €1,501 to €2,200 income bracket, and affects 74% and 50% respectively in medium-sized towns in central and southern Italy.

In fifth place is the lack of company social services (19%), such as nurseries or help with childcare, with a peak in the North-East (38%) where demand, as we have already seen, is highest due to the low incidence of local networks.

Employees: Working conditions explain their dissatisfaction with balancing the education of their children and their professional life

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

These data clearly show that the ‘time factor’ – in terms of both quantity and quality – is at the heart of the perceived malaise in work-life balance, but with significant differences linked to gender, geographical area, income, type of contract and territorial context. Overall, the results are a clear warning to policy-makers: when defining strategies to boost the birth rate, it is essential to create the conditions for genuine equality of opportunity, overcoming territorial inequalities (North-South), disparities between different types of work, gender asymmetries and inequalities in access to services. Only by ensuring a fairer and more sustainable balance between work and family life will it be possible to overcome one of the main obstacles to parenthood.

Corporate social protection, a lever for demographic growth

The survey confirms the growing correlation between the needs of the working population and the opportunities and initiatives that many companies are already adopting or are ready to implement. In this area, the Italian legislation on corporate social protection provides a favourable regulatory framework for the development of measures to reconcile work and family life and support parenthood.

The figures seem to confirm this view. The degree of flexibility shown by employers towards employees, particularly those with children, is the third most popular criterion among those who are satisfied with the way they reconcile work and family (35%). On a national scale, there is a consensus between the different geographical areas in identifying flexible working hours (63%) as the most effective company measure for encouraging childbirth. This result is confirmed across all age groups, both between men and women and between those who have children and those who do not. The percentage for towns with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants is significant in this respect (66%). It confirms the need to adapt working hours due to the lack of adequate essential services, mainly for travel to the workplace.

In second place comes direct financial support (53%), in particular the birth allowance provided by the company, which is of great use according to the youngest (69%) and for people in the South, where the need for additional economic support is more acute. This measure finds widespread support, even above average among those without children (57%). This, combined with the percentage expressed by the youngest respondents, confirms that financial support can be an important incentive or reassurance in the decision to have a first or second child. Even when variables such as marital status, the presence of children, gender or age are analysed, the data show a remarkable homogeneity. It confirms that measures such as flexible working hours and economic support are the subject of a broad and transversal consensus, regardless of the family situation of the people questioned.

This is followed by work-from-home (37%) and company-organised childcare services (27%), which are seen as one of the most desirable measures to help reconcile family and work needs.

The scenario outlined above shows how adapting company policy helps both to promote well-being at work and to build a favourable environment for families and parenthood.

Enabling the future: the meaning of parenthood for Italians who want to have children

Having a child represents a real life project for the majority of Italian respondents with children or wishing to have children (59%) and is more strongly felt by women (67%). These data confirm that parenthood is still seen as a central choice in one’s life.

48% of the sample associate the birth of a child with the opportunity to pass on values, culture and traditions. For 24% of Italians, especially men (30%), having a child means passing on their family name, which reflects a more symbolic and identity-based conception of parenthood. A further 24% of Italians see parenthood as an opportunity for personal development and fulfilment. This figure rises to 28% among the youngest.

16% of those surveyed see having a child as a ‘chance to receive help when I’m older’. This figure rises to 19% among people with a monthly income of less than €1,500 and 18% in the South, showing the extent to which expectations of family support are still deeply rooted in the most fragile regions of the country, where the lack of public services is most marked.

It is also interesting to note the gender differences in this survey: women have children as part of a broader, more integrated vision of their lives, where motherhood is linked to personal identity, relationships and emotional and social fulfilment. Men, on the other hand, tend to be slightly more focused on the symbolic dimension, such as passing on the family name (30%). Overall, the responses indicate that parenthood is still widely perceived as a choice charged with deep cultural, emotional and intergenerational significance, but also as a form of functional response to a social context considered to be fragile, where the family remains the anchor point of reference, even in the absence of adequate public support.

Conclusion

Although some responses may appear contradictory, the present survey is rich in indications for making demographic policies more effective and more in line with social reality.

On the one hand, Italians are very concerned about falling birth rates (79%). On the other hand, however, they seem reluctant to recognise their individual responsibility in solving the problem, even though the study confirms that the desire to become parents is still present in the fertile age bracket. They seem to implicitly say : ‘I recognise the seriousness of the situation, but it is not up to me to find the solution’.

Added to this is a context marked by multiple difficulties and by profound mutations in lifestyles, family models and the scale of individual and collective priorities. The choice to become parents is increasingly conditioned by external factors – economic, professional, cultural – and by a widespread perception of a lack of support from society.

However, the survey also opens up concrete areas for action: a kind of ‘latent social empathy’ emerges between those who have children and those who do not, fuelled by a shared awareness that today’s Italian society is not sufficiently welcoming of children (68% of the sample felt that society does not encourage childbearing and parenthood). This common ground represents a valuable opportunity to develop cross-cutting policies.

For this reason, the results of the survey confer an important responsibility on institutions, civil society and companies. To reverse the demographic trend, it is essential to rediscover, highlight and promote the social significance of motherhood and fatherhood, in particular through positive public narratives that restores the dignity, recognition and centrality of parenthood in the cultural, political and economic debate.

Ultimately, it is important to promote a new partnership between the public and private sectors, capable of identifying the desires, needs and journeys of women and men and transforming them into concrete, structured actions aimed at supporting parental choices.

To this end, it is increasingly necessary to build a kind of ‘birth pathway’ with measures that mark out the different stages in the lives of parents or those who are about to become parents: from the decision to have children to the pregnancy, from combining their work with parenthood thanks to good provisions of childcare services to the choice of secondary school and university education for their children.

The birth rate challenge: A comparison between Italy and France on desire, freedom and responsibility

The demographic comparison between Italy and France

Maxime Sbaihi, Les balançoires vides. Le piège de la dénatalité, Éditions de l’Observatoire, 2025.

Not all crises appear suddenly and traumatically in the course of history. Some gradually penetrate the social fabric and almost imperceptibly end up changing the destiny of nations. Today, low birth rates are a major threat to many Western countries and have long been underestimated. Yet it should be more present in the European public discourse. Year after year, the figures confirm the trend and show that the European population is getting older and older and less and less capable of regenerating itself. To compare Italy and France, we need to look first at the current demographic situation in the two countries.

In Italy, the falling birth rate is now a profound and structural phenomenon. With just 370,000 births in 2024 (-2.6% on the previous year), a total fertility rate (TFR) down to 1.18 children per woman and an average population age of over 46, the country has entered a demographic crisis with tangible consequences for the resilience of the labour market and the viability of the welfare State. It is no coincidence that almost 80% of Italians say they are concerned about the effects of low birth rates on the model of national solidarity.

France also recorded a historic low in 2024 with, 663,000 new births, a fall of 2.2%, marking the lowest level since the Second World War (in 2023, the fall was 6.6%). Its TFR falls to 1.62 children per woman and the average age of the population to over 42. However, it is part of a slightly different dynamic.

If concern about falling birth rates is growing in France (59%), the fertility rate remains slightly higher than in Italy, although it is also falling. In other words, the French perceive low birth rates as a risk, but not yet as an inexorable phenomenon.14 Hence the first difference: in Italy, it is the recurring image of a ‘demographic winter’ that prevails, whereas in France, at least for the time being, the phenomenon seems to be in gestation – a risk that is now clearly emerging and causing concern, but which is not yet having very strong social repercussions.

Disparities between France and Italy are especially visible when analysing the reasons cited by the under-35s for not having children.

In Italy, material reasons predominate: economic difficulties (32% versus 31% for the 35-49 age group) not having a job (21% versus 17%) and difficulties in reconciling one’s professional and personal life (21% versus 11%) and due to insufficient time to devote to one’s family. In France, on the other hand, only 14% of the 18-49 age groups who have no children and do not wish to have any explain this by economic difficulties. As for the parents, 16% of the under-35s and 11% of the 35-49s explained that they did not want any more children because of economic difficulties. The proportion of childless under-35s who do not wish to have children is 25% in Italy and 30% in France. The proportion of 35-49 year-olds who have no children and do not wish to have any is 40% in Italy and 58% in France. If we look at the factors common to both countries, both Italians (53%) and French (52%) believe that ‘today’s world is too dangerous for people to have children’, a sign that the decision not to have children has acquired a cultural and axiological dimension.

Do you think the fall in the number of births is a cause for concern? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

In both countries, the refusal to become parents, understood as the expression of a personal choice or feeling, also plays a major role: in Italy, 21% of under-35s put forward this reason, compared to 19% of women under 35 and 15% of men under 35 in France.

Among those who have no children and do not wish to have any, the under-35s mention personal convictions more often in France (21%) than in Italy (10%). We observe a similar difference for the 35-49 age-group : 31% in France compared with 19% in Italy. This may be the sign of a cultural context in which ideological or axiological choices play a lesser role than material motivations or the mere absence of desire.

In both countries, public support for families and parents is seen as necessary and imperative. Families not only demand more effective policies, they also state their priorities precisely. In France, an approach geared towards services and social rights prevails: 62% of those questioned want tax breaks for families with children, 45% want more childcare facilities and 60% want greater flexibility in working hours. This is not just economic support: it is a vision of parenthood as an integral part of a social system that should support and enable the choice to have children. On the other hand, among the priorities indicated by Italians, social aid and forms of direct support win out, especially in the South (62% compared with a national average of 53%) and among the most economically vulnerable groups: 77% of the sample said they were in favour of tax cuts for families, 51% in favour of increasing family allowances, 39% in favour of making it easier to buy a first home (56% among the younger generations). In France, family well-being is reflected in the development of services and the reconciliation of work and family life. Whereas, in Italy, it remains more linked to the function of redistribution and the logic of compensation. Services and flexibility between private and professional life, although present in Italians’ expectations, rank second after the demand for economic support.

In both countries, parenthood nevertheless retains a strong existential value. 65% of French people and 59% of Italians who have children or want to have children see them as a life project and an experience of self-fulfilment. This figure rises among Italian (67%) and French (72%) women, a sign that motherhood is experienced as an integral part of their identity and personal fulfilment.

What does having one or more children mean to you?

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

There are also similarities between the two countries when it comes to the meaning of parenthood. In Italy as in France, becoming a parent is not just an individual choice and an aspiration for personal fulfilment: it is also an act of generational continuity. Indeed, 48% of Italians and 49% of French people associate the birth of a child with the transmission of values and culture. Differences emerge in some responses: 24% of French people see it as an opportunity to pass on their heritage, compared with 14% of Italians; 16% of Italians see their offspring as a future guarantee of assistance in old age (7% in France), a proportion that rises to 19% among the lowest income groups and 18% in the South, where the family is still an essential social anchor.

For a ‘demographic springtime’

Despite the gloomy atmosphere that hangs over European demographics and that increasingly dominates public discourse, there are signals, perhaps still faint and barely perceptible, that invite us not to give in to resignation. In the dialectic between inertia and demographic awakening, choices and constraints, fear and the will to look ahead, we can discern, in Italy as in France, the roots of a possible ‘demographic springtime’. It is not just a question of numbers. It is the very quality of the desire to become parents that suggests that there is still a deep, vital desire to think about our future through our children.

70% of French people under 35 without children say they would like to have one or more children, rising to 75% for those under 35 who already have one or more children and would like more. Even more interesting is the finding that satisfaction with work-life balance remains high among French parents: more than 75% say they are satisfied with this balance, a percentage that increases further among those who have children and would like to have more (82%). In these social groups, parenthood does not seem to be perceived as an obstacle to personal development, but as part of it.

Do you wish to have children? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

Reasons for cautious optimism also appear in Italy. First, the desire for parenthood remains high among younger people who do not have children: among those under 35, 75% say they want to have children. This figure is increasing even among those who already have one: 79% want to have more. These figures demonstrate that the desire to become parents in Italy has by no means disappeared, but is rather ‘frozen’ and conditioned by contingent obstacles such as job insecurity, difficult access to housing, or insufficient childcare facilities.

Another encouraging sign comes from the world of work. Although uneven and still partial, corporate social protection is also progressing in Italy: 80% of parents say they are satisfied with the measures taken to reconcile work and family time. These data indicate the emergence of an organizational work culture more attentive to the needs of families, fostered by the widespread adoption of flexible working hours, greater listening by employers, and support from parental networks.

The trends we have just described in their complexity paint a less unequivocal picture than the narrative of demographic glaciation alone, according to which we face a future of disappearance and annihilation. This is not about minimizing the problems, nor indulging in facile optimism, but about recognizing that there are foundations on which it is possible to build a birth rate recovery. After all, demography is also about culture, trust, and planning. While it is true that no single policy can reverse long-term historical trends, it is equally true that an alliance between institutions, businesses, and the community can create the conditions for the ever-present desire for children to find the strength to become a reality. It is in this narrow space between desire, freedom, and possibility that far-sighted policy can be developed.

For every springtime, however late, always begins with small signs. And today, both in Italy and in France, these signs – amid a thousand contradictions – are beginning to appear.

Divergent sociologies

Other aspects of the comparison between the responses of the Italians and the French are worth exploring in greater depth, as they enrich our understanding of the socio-cultural dynamics that distinguish the two countries faced with the demographic challenge. In France, religion plays a key role in demographic dynamics : among the under-35s, Catholics (79%) and Muslims (84%) are more likely to want children. This impetus is weaker among people with no religion and the No Kids, who do not see parenthood as a natural extension of the life cycle.

In Italy, religion does not appear to be a significant variable, but it does loom large in certain indices, in particular in the perception of the birth rate as a problem (83% of Catholic respondents say they are concerned) and in the belief that society does not encourage parenthood (68% of respondents share this concern), which is more prevalent among right-wing sympathisers (70%) and Catholics (71%). In Italy, the religious factor seems to be fuelling a heightened awareness of the crisis and the collective responsibility it implies.

Eco-anxiety (i.e. fears linked to the environmental and climate crisis) was suggested to respondents as one of the reasons for giving up on parenthood. While 20% of French people believe that ‘having a child means jeopardising the future of the planet’, it remains a concern for a minority of young respondents and No Kids (31%). In Italy too, the environment is an issue for young people (21%), who are more likely than the rest of the population (15%) to think that ‘to have a child is to jeopardise the future of the planet’ – although this is not a central motivation in the definition of reproductive choices.

‘To have a child is to jeopardise the future of the planet’ (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

In Italy, the declining birth rate ‘goes hand in hand’ with territorial inequalities, both in their traditional historical form, namely the divide between North and South, and in their new form between urban centres and ‘fragile areas’, the interior and the periphery. In any case, this complicates the construction of a unified demographic policy. Northerners demand policies geared toward well-being and services, and therefore daycare centres, flexibility, and work-life balance. Southerners express a stronger preference for social assistance and direct economic aid, which immediately respond to their material and social protection needs.

Although in different social and political contexts, both countries share a growing and cross-cutting concern about the systemic consequences of the falling birth rate: the question of the sustainability of social protection and pension systems is a significant issue in French and Italian public opinion.

In France, 53% of the population fears that declining birth rates will compromise the viability of the pension system, and 49% say they are concerned about the consequences for the health and social protection system. Among those over 50, this concern rises to 58%, a sign of a growing perception of risk among those approaching retirement.

Italy is no less sensitive to this dimension. When Italians are asked about the main consequences of declining birth rates, they clearly give two answers: 52% fear that it will jeopardize the viability of the pension system, while 51% fear risks to the health system and social protection in general. This concern is transpartisan, although it is more pronounced among left-wing voters, who are historically more sensitive to social protection issues (58% are concerned about the viability of the pension system and 57% about the health and social protection system).

Corporate social protection is widely accepted in both countries, albeit with different values. In France, it is seen as an established right and an inalienable prerequisite of the workplace. Flexible working hours, parental leave and work-from-home are not just occasional aids, but are seen by the French as an integral part of a model that seeks to recognise and protect family life. 60% of the sample, in particular, see flexible working hours as the winning weapon for reversing the birth rate trend. In Italy, corporate social protection is seen as an emerging opportunity: available to varying degrees depending on the sector and geographical area, it tends to be seen more as an additional benefit than as a fully acquired right. This distance reflects two different historical models of industrial relations and trade union relations: on the one hand, the consolidation of now standardised practices and, on the other, the still partially unfulfilled aspiration to make company social protection a generalised and structural support for parents.

Would you be in favour of encouraging immigration to tackle falling birth rates? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondapol | Fondazione Magna Carta – June 2025

Finally, Italy and France are united by a complex and ambivalent debate on immigration as a possible lever for countering demographic decline. In both countries, welcoming new citizens is not seen as an automatic solution to demographic decline, but neither is it totally ruled out.

In Italy, the issue literally divides public opinion in two. When asked about the need to encourage immigration in order to tackle falling birth rates and its consequences (ageing, labour shortages, continued social assistance), the sample was divided between 43% in favour, 43% against and 14% with no opinion. Some groups were more supportive of immigration than others: men (48%), young people (59%) and people from the South (47%). Politically, left-wing supporters are much more in favour (57%) than right-wing supporters, who are largely opposed to this option (59%).

In France, when asked whether immigration should be encouraged to counter falling birth rates, 60% were opposed to immigration, while only 29% were in favour. While recognising the contribution of immigration, many French people are aware that it is not a structural and definitive solution. Indeed, over time, even among immigrants, the fertility rate tends to fall as they integrate into society and adopt modern European cultural and social practices.

Conclusion

The comparison between Italy and France paints a picture that retains promising elements. In both European countries, young people’s desire to have children is still present and, in some cases, surprisingly alive. This finding, common to both surveys, indicates that parenthood, although subject to cultural, material and axiological tensions, has not been pushed off the horizon of individual and collective aspirations. The youth continues to represent a demographic potential. However, the two countries differ profoundly in the ways in which this desire is expressed, and even more so in the conditions that facilitate or hinder its realisation.

France has a stronger and more widespread desire to have children, a sign of a more favourable context and a public culture that has historically made birth rates a matter of national interest. The tradition of family policies, based on services, transfers and an inclusive idea of well-being, has helped to make the choice to have children less burdensome for the French.