The myth of a racist France (1)

Racialism, the history of a failureSummary

Expressed in terms such as “structural racism” or “systemic racism”, particularly harsh accusations have been levelled at France in recent years. These accusations, which have never been seriously substantiated, are all the more unfair in that they are in flagrant contradiction with a national history that is profoundly resistant to theories of race. The first part of this paper sets out to analyse the main reasons why, over time and as a result of a series of original conjunctures and bifurcations, the question of race has been neutralised.

This long-term process, the fruit of conditions specific to the history of France, is based on a multitude of decisive factors that this text seeks to analyse: the Christian heritage, exogamous marriage,the sociology of the aristocratic elites, the value placed on education, the conception of the nation and the attitude of intellectuals.

Vincent Tournier,

Senior lecturer in political science, Grenoble Institute of Political Studies.

Introduction

Vini Lander, “Structural racism: what it is and how it works”, The Conversation, 30 June 2021, [online]; Pierre-André Taguieff, L’antiracisme devenu fou. Le « racisme systémique » et autres fables, Hermann, 2021.

A review would be long and tedious. An overview can be obtained by searching for the expressions “systemic racism” or “structural racism” on the academic website The Conversation, which is available in several countries. For Canada, see the document “Combating systemic racism and discrimination in Canada” available on the government website.

. See « Racisme institutionnel », Multitudes, vol.4, n°23, 2005 ; « Un racisme institutionnel en France? », Migrations et Société, vol. 1, n°163, 2016. Some academics adopt ambiguous positions. Political scientist Patrick Weil, for example, explains in a programme entitled « Racisme structurel » that “the notion of ‘structural racism’ should be used with great caution. I think that in France we have a form of politics that has institutional racism” (« Les sociétés face au racisme structurel », France culture, 8 June 2020). In 2017, the historian Pap Ndiaye, future Minister for Education, disputed the expression « racisme d’État » (“state racism”) defended by Sud-Education 93, but sustained that “there is indeed structural racism in France” (« Pap Ndiaye : ‘Il existe bien un racisme structurel en France’ », Le Monde, 18 December 2017).

“Seminal UN report offers an agenda to dismantle systemic racism”, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, United Nations, 29 June 2021. The expression “systemic racism” can be found on the websites of the Council of Europe and the European Commission, or on the websites of numerous NGOs (see, for example, “Structural racism” on the website of the NGO Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies).

IFOP poll for l’Express conducted on 23 and 24 February 2021 among 1011 people aged 18 and over.

IFOP poll for Sud Radio conducted on 16 and 17 June 2020 among 1,020 people aged 18 and over.

William Macpherson, The Stephen Lawrence inquiry, February 1999.

“Structural racism”, Cambridge Dictionary [online].

Fabrice Dhume, « Du racisme institutionnel à la discrimination systémique ? Reformuler l’approche critique », Migrations Société, vol. 163, n° 1, 2016, pp. 33-46 [online] ; Valérie Sala Pala, « Faut-il en finir avec le concept de racisme institutionnel ? », Regards Sociologiques, n°39, 2010, pp.31-47 [online].

Michel Foucault, « Il faut défendre la société », Cours au Collège de France (1975-1976), 2012 [online].

The term “racism” refers to individual attitudes, while the term “racialism” refers to ideas and representations based on race.

“State racism”, “structural racism”, “institutional racism”, “systemic racism”: all these expressions, and many others such as “White privilege” or “whiteness”, have become commonplace.1 Although they are less common in France than in North America or the UK,2 they are now widely used by some of the elite3 and international institutions.4 They have also won over a large proportion of the public, particularly young people. In February 2021, 54% of French people thought that “systemic racism” was a reality (66% of those under 35)5 and 30% of French people (47% of those aged 18-24) thought that “state racism” was a reality.6

Between June 2020 and February 2021, the proportion of French people who consider “White privilege” as a reality rose from 32% (52% among the under-35s) to 46% (61% among young people).

What do we mean by structural, systemic or institutional racism – terms that are relatively interchangeable? The term “institutional racism” appeared in 1999 in a British report on the murder of a young Black man by the police (the Macpherson report) and refers to all processes which, based on racist stereotypes, disadvantage members of ethnic minorities.7 As for structural racism, it is defined by Cambridge Dictionary as “laws, rules, or official policies in a society that result in and support a continued unfair advantage to some people and unfair or harmful treatment of others based on race”.8

Based on these definitions, it seems obvious that France is not concerned, since one would be hard-pressed to find traces of racialism in its legislation and institutions. But the problem does not end there. The use of the terms “system” or “structure”, which have a rich history in the social sciences, designates interrelated elements whose assembly forms a coherent whole, implying that the phenomenon is widespread and omnipresent. To say that racism has a structural or systemic dimension means that it is endemic in nature and that it is embedded at the very heart of institutions and society; in short, it permeates the policies of the State as well as the culture of society. In the case of France, such an analysis comes up against a dead end: there are too many anomalies for it to be seriously accepted. Even its supporters are uncomfortable – and with good reason: in the history of France, everything goes against the thesis of structural or systemic racism. 9

This contradiction is not enough to shake convictions, however. For the proponents of structural racism, even if racism is not explicitly visible in legislation, it nonetheless permeates the workings of institutions and society. French society is therefore accused of being based, then as now, on an enterprise of domination and exclusion based on race, as Michel Foucault already argued in 1976 when he explained that every society knows a “race war”, and even that every power bases its domination on a “state racism”.10

It is, however, the exact opposite thesis that this text proposes to defend, namely that French society, because of its specific culture and history, has been constituted on a basis that is profoundly resistant to racialism and racism.11 In saying this, it is not a question of denying the existence of racism, nor of falling into a historical determinism that would replace one culturalism with another.

The thesis that this text aims to support is rather that, over the course of time, under the effect of constraints and singular circumstances, French society has followed a series of bifurcations that have led it to reject racism. This path was not a foregone conclusion; it was the result of a combination of ingredients that led to an original situation that could be described, even if it sounds grandiloquent, as the “French miracle”.

Once this has been established, this text will examine why a thesis as far removed from reality as that of structural or systemic racism has been able to develop and gain ground – a line of inquiry that will require a detour through the analysis of myths.

To understand the French situation, we need to look back at the long-term mechanisms that have shaped the collective psychology of the French, particularly that of the elites. These mechanisms worked by sedimentation: they accumulated over time, building up successive layers of an intellectual and cultural environment unfavourable to the ideology of race.

The Rejection Of Racialism: Anthropological Foundations

An Egalitarian Culture

Louis Dumont, Essais sur l’individualisme. Une perspective anthropologique sur l’idéologie moderne, Seuil, 1983.

Alain Laurent, Histoire de l’individualisme, PUF, Que Sais-Je, 1993

Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau, Les Traites négrières, essai d’histoire globale, Gallimard, 2004. See also Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau, « Le siècle des abolitionnistes », L’Histoire, 353, May 2010.

The rejection of racialism is inseparable from the egalitarian culture that developed in France long before the French Revolution. This culture is the fruit of a long history that owes much to the process of state-building which, as Tocqueville analysed, went hand in hand with an individualist ethic.

The Christian heritage formed the backdrop to this egalitarian culture. By enshrining principles such as the dignity and equality of men, on which modern natural law has been able to develop, Christianity has fostered a humanist and universal conception that has valued the individual to the detriment of a holistic vision of society.12

Saint Paul’s famous formula in the Epistle to the Galatians (“There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus”) has favoured a monogenist conception of the world, a thesis that attributes a single origin to the whole of humanity, as opposed to the polygenist thesis.

It was from this Christian foundation that the Renaissance, and later the Enlightenment, were able to build a universal representation of man. Examples include Pico della Mirandola, who extolled the “dignity of man”, Descartes, for whom “common sense is the most widely shared thing in the world”, and Rousseau, who sought to address “the only animal endowed with reason, that is, man”. These authors had a complex – and sometimes conflicting – relationship with Christianity, but they were nonetheless steeped in religious references. From this matrix emerged the “individualist paradigm”, the basis of modern political thought.13

These principles of dignity and equality, forged by Christianity and taken up by Western philosophy, made slavery morally unacceptable, leading to its abolition. This is a major originality, as all other civilisations, including ancient civilisation, saw slavery as a fact of nature. Only the Christian West was able to bring about an abolitionist movement.14

At the same time, the emphasis on dignity and equality may have given rise in the West to a feeling of moral superiority over other civilisations. Today, this feeling of superiority is denigrated, but it was partly the result of this universal conception of the individual and his rights. At the famous Valladolid debate, convened by Emperor Charles V in the mid-sixteenth century, the Spanish jurist Sepulveda justified the conquest of the Indies (the Americas) by the right of superior peoples to civilise savage peoples. This argument may come as a shock, but it stems from the denunciation of practices deemed barbaric, such as cannibalism and human sacrifice, which were in fact quite real and unknown in Europe.

While the West has not escaped the thirst for conquest, it has distinguished itself by its desire to accompany its expansion with the transmission of humanist values. This ambition was not exclusive of other, less respectable objectives, nor of aberrations or hypocrisy, but it nonetheless constituted an important singularity in relation to other civilisations, as can still be seen today in the all-Western tradition of humanitarian intervention or welcoming foreigners – a passion not unlike the Christian injunction to love one’s neighbour.

Christian Marriage: Exogamy and Alliances

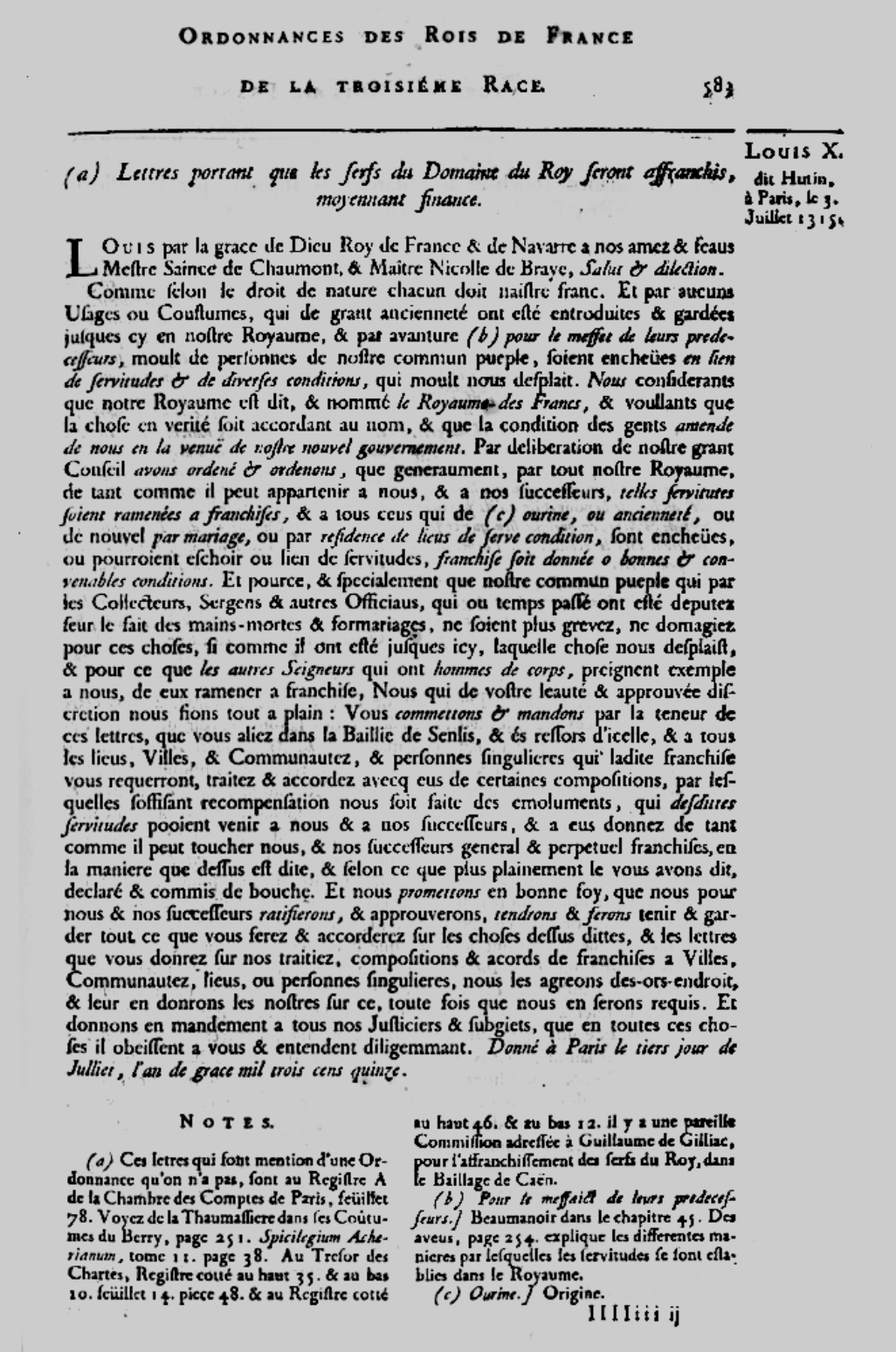

However, Christian culture does not explain everything. Religious values can be interpreted in a variety of ways and can lead to very different cultures. A comparison between France and other Christian countries suffices to show this – including on the issue of slavery, which continued in the southern United States until 1865, or in Orthodox Russia until 1861, whereas it was abolished in France as early as 1315 by King Louis X the Quarrelsome.

3 July 1315: Louis the Quarrelsome abolishes serfdom

Source :

« Ordonnance royale du 3 juillet 1315 » in Eusèbe Jacques de Laurière, Ordonnances des rois de France de la troisième race, Volume 1, 1723, p.583 [online].

| Transcription in modern English of the order of King Louis X, known as the Quarrelsome

“Louis, by the grace of God, King of France and Navarre, to our dear and faithful masters Saince de Chaumont and Nicolle de Braye, greetings and affection. Since, according to natural law, everyone must be born free, and since, due to certain practices and customs established since great antiquity and preserved until now in our kingdom, and sometimes because of the faults of their predecessors, many of our common people have fallen into servitude and various conditions which greatly displease us. Considering that our kingdom is called the kingdom of the Franks and wishing that the reality correspond to this name, as well as to improve the condition of the people under our new government, we have, after deliberation in our great council, ordered and ordain that, generally, everywhere in our kingdom, insofar as it belongs to us and our successors, these servitudes be brought back to freedom. Thus, all those who, by origin or seniority, or recently by marriage or residence in places of servile condition, have fallen or could fall into servitude, will be granted freedom under just and suitable conditions. And in order that our common people may no longer be burdened or wronged by the collectors, sergeants and other officers who, in the past, have been charged with collecting the duties of mainmorte and formariage, as has been the case until now, which we dislike, and so that the other lords who possess hommes de corps may follow our example and free them in their turn, we, who have full confidence in your loyalty and wisdom, commission and mandate you, by the content of these present letters, to go to the baillie of Senlis and its jurisdictions. There, in all places, towns, communities and with all singular persons who will claim this freedom, you will have to deal and conclude with them certain compositions, by which we receive sufficient compensation for the revenues that these servitudes could provide us and our successors, and grant them, insofar as it belongs to us and our successors, a general and perpetual freedom, according to what has been said above and what we have more fully declared and entrusted to you orally. And we promise in good faith that we, for ourselves and our successors, will ratify and approve, hold and will hold and observe all that you will do and agree on these subjects. As for the letters which you will issue for the treaties, compositions and agreements of emancipation of towns, communities, places or individuals, we accept them as of now, and will provide them with our own letters in this matter, whenever we are required to do so. And we give instructions to all our judges and subjects to obey you in these matters and to give you all due diligence. Given in Paris, on the third day of July in the year of our Lord 1315”. This transcription is partly taken from Louis Dussieux in L’histoire de France racontée par les contemporains, Tome III, Imprimeurs de l’Institut, Paris, 1861, p. 30. |

A vast study carried out by a team of researchers has shown that Christian prohibitions on consanguinity have had very significant effects on the development of values such as individualism and trust. Shulz et al., “The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation”, Science, 8 November 2019 [online].

Jack Goody, L’évolution de la famille et du mariage en Europe, Armand Colin, 1985.

Marie-Louise Surget, « Mariage et pouvoir : réflexion sur le rôle de l’alliance dans les relations entre les Evreux-Navarre et les Valois au xive siècle (1325-1376) », Annales de Normandie, 2008, 58(1-2), pp. 25-56.

The Christian religion is therefore not a sufficient condition. Other factors must be taken into account, starting with Christian marriage as imposed by the Church.

Introduced by the Gregorian reform of the eleventh century, Christian marriage prohibited a wide range of unions on the grounds of consanguinity (seven degrees of kinship, reduced to four at the Lateran Council in 1215). This exogamous norm meant that wives had to be exchanged outside the group to which they belonged. The exogamous model is not found in other civilisations, where endogamous marriage between cousins is sometimes highly valued, going hand in hand with strong control over women.

The Christian concept of marriage, which the aristocracy tried to resist, had a considerable impact on morals.15 By delegitimising the blood ties on which pagan marriage was based, Christian marriage obliged people to find a spouse outside their clan or lineage, sometimes even outside the aristocracy, thereby reducing the importance of race. At the same time, the Church has distinguished itself by the importance given to spiritual kinship (godmothers and godfathers), which has been given the same importance as biological kinship, thus another way of relativising the importance of blood.16

With Christian marriage – whose other characteristics are monogamy, indissolubility and the consent of the spouses – the aristocratic elites were forced to broaden the scope of their alliances, which encouraged them to overcome clan ties and pacify morals.17

The Relativisation of Blood Ties in the Aristocracy

Furetière’s dictionary defines race as follows: “Lineage, a succession continued from father to son: a term that refers to both ancestors and descendants” (quoted by Daniel Teysseire, « De l’usage historico-politique de race entre 1680 et 1820 et de sa transformation », Mots, n°. 33, December 1992).

Arlette Jouanna, La France du xvie siècle, 1483-1598, PUF, Quadrige, 2009 [1996]

Norbert Elias, La civilisation des mœurs, Calmann-Lévy, 1973 [1939].

Originally, the aristocratic elites strongly promoted the ideology of race, understood in its original sense of lineage or genealogy.18 This ideology attributed superior qualities to noble blood, thereby justifying the domination of an elite, as was the case in all pre-modern societies.

However, the French nobility has undergone profound changes that have put the role of lineage into perspective. Contrary to popular belief, the nobility has never been a totally closed order.19 In addition to ennoblement through arms – the importance of which stemmed from the frequency of wars – there were two other types of ennoblement: ennoblement through the exercise of offices (referred to as enobling) and ennoblement through the will of the king, who eventually imposed his monopoly on access to the nobility.

The letter of ennoblement was both a way for the king to surround himself with loyal and talented people, and an adjustment variable to fill the kingdom’s coffers, particularly after the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) and the American War of Independence (1775-1783), which were very costly for the monarchy.

The nobility was constantly changing and diversifying. This mix explains why the rules of civility and decorum were scrupulously codified in aristocratic circles dominated by the noblesse de robe. Forced to rub shoulders and shine in front of the king, aristocrats had to compete in manners. Civility was the key to being recognised as an aristocrat and to standing out from the crowd.20 Molière drew on this rivalry in one of his most famous plays, Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, written at a time when Louis XIV was promoting a number of wealthy bourgeois to consolidate his administration and power.

The Cult of Meritocracy

Olivier Tholozan, Henri de Boulainvilliers : L’anti-absolutisme aristocratique légitimé par l’histoire, Presses universitaires d’Aix-Marseille, 1999 [online].

Paradoxically, it was this desire to reaffirm the pre-eminence of the old nobility at the expense of the king that contributed to the success of Montesquieu’s liberal ideas: his thesis on the separation of powers provided an additional argument for aristocrats opposed to absolute monarchy. See Jean-François Jacouty, « Une contribution à la pensée aristocratique des Lumières. La théorie des lois politiques de la monarchie française de Pauline de Lézardière », Revue Française d’Histoire des Idées Politiques, vol. 17, n°1, 2003, pp.3-47. See also Jacques de Saint-Victor, La Chute des aristocrates. 1787-1792 : naissance de la droite. Perrin, 1992.

Rafe Blaufarb, « Une révolution dans la Révolution : mérite et naissance dans la pensée et le comportement politiques de la noblesse militaire de province en 1789-1790 », Histoire, économie & société, vol. 33, n° 3, 2014, pp.32-51.

Ludmila Pimenova, « Analyse de cahiers de doléances: l’exemple des cahiers de la noblesse », Mélanges de l’École française de Rome. Italie et Méditerranée, vol. 103, n° 1, 1

Arlette Jouanna, La France du XVIe siècle, op. cit.

Éric Saunier, « Comment les francs-maçons devinrent révolutionnaires », in Peuples en révolution : d’aujourd’hui à 1789, Presses universitaires de Provence, 2014; from the same author, « Les francs-maçons et la Révolution française », in La Franc-maçonnerie, virtual exhibition at the BNF, 2014 [online].

However, the inflation of noble titles had its downside: it provoked criticism from the traditional nobility, known as the nobility of extraction, which claimed to embody the authentic nobility by virtue of the antiquity of their lineage and their aristocratic way of life.

In order to sideline or disparage the newcomers, long-aristocrats emphasised bloodline and race. They also sought to justify their pre-eminence with the so-called “Germanist” theory of nobility, according to which nobles descended from the ancient Franks.21 The aim of this theory was to undermine the nobility of the new aristocrats, on the grounds that true aristocrats were presumed to be of Frankish descent). For the traditional aristocracy, it was also a question of defending their rights in the face of the absolute power of the king, while simultaneously asserting their natural superiority in the face of a fast-growing senior administration, which had become independent due to the venality of offices. 22

This noble backlash, which became more pronounced towards the end of the Ancien Régime, exasperated both newly minted aristocrats and bourgeois aspiring to nobility. Yet while these new aristocrats criticised the nobility by extraction, they also envied its prestige and pre-eminence, as it enjoyed an almost exclusive access to the highest military and ecclesiastical positions.23 The haughty attitude of the old aristocratic families, which can be seen in the cahiers de doléances, was all the more difficult to accept as the old lineages were forced to live in idleness.24 If they did not want to fall into disgrace they had to avoid indulging in activities deemed vile, in this case manual labour or trade.25

In this competition among the elites of the Ancien Régime, the ideology of race therefore presented itself as an obstacle and a threat to the social success of the recent nobility. This is why this ideology was strongly rejected in favour of another criterion: merit.

The traditional nobility’s cult of blood and good manners was thus met with a counter-cult of work and merit. This is demonstrated in a famous line from Le Mariage de Figaro (“You took the trouble to be born, and nothing more”) and, later, in Saint-Simon’s famous parable, which cruelly contrasts the idleness of hornets with the fruitful work of bees.

A Cultural Environment Rooted In Anti-Racialism

This initial framework must be supplemented with other elements that have contributed to enriching and deepening the cultural foundation hostile to racialism. These elements include an attachment to the decisive role of education, a social conception of filiation, an open vision of the nation and the valorisation of the very French notion of assimilation.

Faith in Education

“One does not always follow one’s forefathers or one’s father / Lack of care, time, all make one degenerate / For want of cultivating nature and its gifts / O how many Caesars will become Laridons!”, Jean de la Fontaine, « L’Éducation », Selected Fables, Book VIII, fable 24, 1678 [online].

The belief in the power of education added a powerful antidote to race theory. This belief is so ingrained in national psychology that, even today, schools are instinctively called upon to solve all society’s problems.

The value of education predates Jules Ferry by long. It is the fruit of a long evolution that combines a cultural and a political component.

On the cultural side, we find the Christian concept of “soft wax”, a concept that appeared in the twelfth century before being taken up in a secularised form by the philosophers of the Enlightenment through the notion of “perfectibility” (Rousseau). This concept states that human nature is sufficiently pliable to be moulded at the whim of educators.

It owed its success to the fact that both the aristocratic and bourgeois elites viewed it favourably. Race paid the price, as confirmed by La Fontaine’s fable entitled “Education”. In this fable, inspired by Plutarch’s The Education of Children, which was very popular in the sixteenth century, La Fontaine describes the contrasting fates of two dogs of the same breed, César and Laridon. Only César, who is well fed and well educated, remains true to his rank. The fable ends with an ode to education, which is the only way to preserve a “happy nature”.27 The emphasis on education has had the effect of refocusing the family on the conjugal unit. This refocusing took place first in affluent circles before spreading to the rest of society, as Philippe Ariès has analysed.28 Children have become a value in which parents invest. They are the object of affection and attention, which has led to a drop in the birth rate. The first years of education are now spent within the family.

In addition, political and religious divisions served to consolidate attachment to education. At the time of the Reformation, the Church had to respond to the challenge posed by Protestantism, which sought to free itself from the mediation provided by the clergy in its relationship with God. The Catholic Counter-Reformation was therefore largely played out in the field of education.

But by defining itself as a teaching institution, the Church in turn came under fire from the secular camp. The Jesuits, whose order was created in 1540, were the first to be targeted. In his Essai d’éducation nationale (1763), the spark of an education war that would last for more than two centuries, Louis-René de La Chalotais explained that the Jesuits should be driven out of teaching and that education should be entrusted to the State.

What is at stake in this opposition between the Church and the State is none other than control over the education of children. The competition is all the more fierce because both sides share a belief in the omnipotence of education and in the mediating role of the institution. In the same way that the Church sought to mediate between God and the faithful for the salvation of souls, the Republicans saw in the State an instrument to take charge of the destiny of the Nation, provided of course that the secular clergy was replaced by a lay clergy, which would be ensured by the “Black hussards” of the Republic.

Social Filiation versus Biological Filiation

“A child conceived or born during marriage has the husband as its father” (article 312 of the Civil Code). It should be noted that the 1972 law stipulated that “Nevertheless, the husband may disavow the child in court if he can prove that he cannot be the father”. This sentence was deleted in 2006, thereby weakening the possibility for fathers to contest filiation.

The French ‘allergy’ to race also stems from the distancing of biological filiation. This relativisation stems from two concerns: public order and natalism. French statism encourages families to be peaceful and stable, to the detriment of biological truth.

French civil law was built on the principle of social paternity, in keeping with the Roman adage Pater is est quem nuptiæ demonstrant – the father is the one whom marriage indicates – reproduced identically in the French Civil Code.29

Legally, marriage creates a presumption of paternity, such that the father is the same as the husband. When couples are not married, paternity is established by a declaration of acknowledgement which, once established, is difficult to contest. In the absence of an acknowledgement, paternity is imposed by the courts without the need to provide biological proof: it is then sufficient to establish possession of status by an act of notoriety, in other words to demonstrate with the help of witnesses that a filial link exists (article 310-3 and seq. of the French Civil Code).

The aim of social paternity is to preserve order in families. Priority is given to the legal stability of the family, because of its far-reaching implications (civil status, education, inheritance). This is why paternity proceedings were severely restricted. It was not until 1912 that it was authorised by law. However, it was restricted to legal proceedings and was therefore subject to the judge’s discretion and to the person’s written consent (in the Yves Montand case, a particular difficulty arose because a claim of filiation was made post-mortem, which turned out to be false). All private research is strictly prohibited (article 16-11 of the French Civil Code). In the event of infringement, the penalties are up to one year’s imprisonment and a €15,000 fine.

The Napoleonic Code also took up another principle of Roman law: adoption. In force in Antiquity, adoption was outlawed under the Ancien Régime, which was consistent with the ideology of race. Restored by the Civil Code, French adoption differs from adoption under the Roman Empire, but also from adoption in traditional societies (fa’a’amu in Polynesia) or Islamic societies (kafala) in that it creates a genuine legal filiation. Adoption may be a minority phenomenon, but its presence in the law nonetheless reveals the very social conception of kinship.

In the case of mothers, where the biological link is not in dispute, it was concern for the birth rate that led to the introduction of an original system, in this case anonymous childbirth, also known as childbirth “under X” in France. Concerns about the French birth rate were heightened at the end of the nineteenth century, not least because of rivalry with Germany. The carnage of the First World War reinforced this concern, as shown by a number of measures: the 1920 law on contraception, debates on the family vote and the creation of family allowances in 1932. Births under X first appeared in 1904 (the prefect could waive the right to produce a birth certificate) and were later formalised in the decree-law of 2 September 1941, still in force, which allowed mothers to renounce their maternity without fathers being able to assert their rights.

All these elements form an anthropological foundation that has never been called into question, despite the challenges. The legislator still refuses to legalise genetic testing. Penalties have even been increased, so that those who still wish to reconstitute their origins have no choice but to turn to companies based abroad.

Even more significant is the fact that anonymous births have not been repealed, despite the fact that this system is in flagrant contradiction with the right to know one’s origins, proclaimed by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). The laws of 2002 and 2009 made it easier to lift maternal anonymity, but the law still gives mothers the option to keep their identity secret if they wish, which was validated by the French Constitutional Council (question prioritaire de constitutionnalité – QPC of 16 May 2012). Fathers, for their part, have an extremely short period of time after the birth (two months) in which to block an adoption procedure in the event of a birth under X. The shortness of this period has also been accepted by the Constitutional Council in the name of the need to guarantee children a stable family environment, a principle that has therefore been deemed superior to respect for biological paternity (QPC decision of 7 February 2020).

An Open Conception of the Nation

Walter Bruyère-Ostells, « Les étrangers dans les armées françaises de 1789 à 1945 », Inflexions, vol. 34, no. 1, 2017 [online].

In 1993, the Constitutional Council refused to include droit du sol among the fundamental principles recognised by the laws of the Republic, arguing that the law of 1889, which introduced droit du sol subject to a residence requirement, primarily met the needs of conscription (decision of 20 July 1993).

Bronwen Manby, « Les lois sur la nationalité en Afrique : Une étude comparée », Open Society Foundations, October 2009 [online]

Enest Renan, « Qu’est-ce qu’une nation », conference at the Sorbonne, 11 March 1882.

A number of economic, demographic and military factors combined to develop an open concept of nation and nationality.

Won over early by the Industrial Revolution, and unlike the rest of Europe, France has been a land of immigration since the second half of the nineteenth century, first of European origin, then of North African and African origin after 1945.

If this immigration was able to take place, it was because it benefited from a favourable context. The Kingdom of France was made up of several disparate territories and populations (formerly known as races) that had to coexist, encouraging people to transcend ethnic barriers. What’s more, France was often at war, not least because of its geographical location, surrounded by countries with hegemonic ambitions (England to the north, Germany to the east, Spain to the south).

Because of its many wars, and out of concern for its birth rate, France continually called on foreigners to bolster its armies. Entire regiments of foreigners (Irish, Swedes, Italians, Croatians, Poles, Swiss, Germans, etc.) served France under the Ancien Régime. This mix did not disappear with the creation of a national army under the Revolution.30 Foreigners continued to serve in large numbers, from the Revolutionary and Napoleonic armies through to the World Wars, not forgetting the colonial armies (Senegalese riflemen, Moroccan, Algerian and Tunisian spahis).

The famous Légion Étrangère (Foreign Legion), created in 1831 in response to the colonisation of Algeria, is emblematic of this integration through arms, via the impôt du sang (blood tax, a military service obligation tax).

In 1912, military service was extended to people from the colonies without difficulty, which is no mean feat in a country that closely associates citizenship with carrying arms. This situation outraged German troops, who did not hesitate to massacre Senegalese riflemen in June 1940. In 1939, a law decree invited beneficiaries of the right of asylum to join the French army in exchange for naturalisation.

On the strength of this geopolitical and demographic situation, France has introduced an original system of nationality law that combines the droit du sang (right of blood) and the droit du sol (right of soil). Contrary to popular belief, droit du sol is neither an invention of the French Revolution nor a principle exclusive to French law. First introduced in 1851 in the form of the double droit du sol (double right of soil), it was extended in 1889 in the form of a droit du sol partiel (partial right of soil), granted not at birth but at the age of majority, subject to a certain period of residence.

Under this legislation, nationality is not granted automatically at birth, as would be the case under a genuine droit du sol, but after a process of “socialisation”.31 The 1889 law is based on the principle that anyone born in France becomes French as a result of acculturation. In other words, you are not born French, you become French.

By introducing place of birth as a criterion for nationality, France set itself apart from the other countries of continental Europe, in which nationality criteria are often based solely on the right of blood. It stands even more radically apart from African countries which, not content with ignoring the right of soil, often have a difficult, discriminatory and partial naturalisation procedure, sometimes explicitly racial or based on religion, as is the case in North Africa.32

The French approach was pragmatic: the aim was to give French citizenship to foreigners arriving in France in order to increase the country’s demographic and military power, but also to avoid resentment against foreigners exempt from military obligations. The 1889 law was also intended to cut off the risk of Spain or Italy making territorial claims over Algeria, since each of these two countries had a large diaspora there.

After the 1914 war, the 1927 law further facilitated naturalisations to make up for the bloodshed in the trenches.

Priority was given to demography to the detriment of race and genealogy. The rejection of race in the definition of the nation was forcefully set out by Ernest Renan in his famous 1882 lecture at the Sorbonne.33 In his plea, which has become emblematic of the French conception of the nation, Ernest Renan firmly dismisses race (as well as other criteria such as language or religion) in favour of will alone: a Frenchman is one who has “the will to continue to make use of the inheritance he has received undivided”. While the cult of ancestors did not disappear, it took on a collective and mythological meaning for Renan: “The cult of ancestors is the most legitimate of all; the ancestors made us what we are. A heroic past, great men, glory (and I mean real glory), that is the social capital on which a national idea is built. To have shared glories in the past, a common will in the present; to have done great things together, and to want to do them again, that is the essential condition for being a people”.

While this definition of the nation is intended to justify French claims to the territories lost in 1871 (Alsace and Moselle), it is based on an idea that runs through the history of French nationalism: France is first and foremost the result of a voluntary commitment. In a way, by emphasising willpower, Ernest Renan was reviving the Christian tradition, which sees membership of the Christian community as a personal and spiritual choice.

Assimilation: A French Dream

Abdellali Hajjat, « Généalogie du concept d’assimilation. Une comparaison franco-britannique », Astérion, n°8, 2011.

Diderot, Réfutation suivie de l’ouvrage d’Helvétius intitulé l’Homme, 1774

Ernest Renan, op. cit.

See Jean-Marc Chouraqui, « Les communautés juives face au processus de l’émancipation », Rives nord-méditerranéennes, 14, 2003 [online].

Pierre Birnbaum, Les fous de la République, Fayard, 1992.

Similar criteria apply in the United States, where naturalisation is conditional on length of residence, language proficiency, morals, knowledge of US history and loyalty to the Constitution and the nation.

The French concept of nationality is inseparable from a principle that has characterised national history: assimilation. This concept, which is structurally opposed to race, has a long history. It was in the fifteenth century that the word emerged to designate the act of “making similar”.34 It was then influenced by Christianity in the dual sense of communion with God and entry into the community of believers (as opposed to excommunication).

The word then underwent a process of secularisation under the influence of the natural sciences. The dictionary of the Académie française defines assimilation as “an action by which things are made similar” (1762), a definition also found in L’Encyclopédie. Diderot used assimilation to explain, in response to Helvétius, that assimilation equalises individuals in that it “blurs the ranks” and cancels out the lineage.35

The idea was broadened in the nineteenth century with the building of the nation. Ernest Renan used the metaphor of a cauldron to describe the fusion of races: “The Frenchman is neither a Gaul, nor a Frank, nor a Burgundian. He is what has emerged from the great cauldron where, under the presidency of the King of France, the most diverse elements have fermented together”.36

It was with the Jewish question that assimilation was implemented in an almost idealistic way.37 The early days of the Revolution were not favourable to the Jews, who were excluded from citizenship. Stanislas de Clermont-Tonnerre, a liberal monarchist deputy, came to their defence: “We must deny the Jews everything as a nation and grant them everything as individuals; they must not form either a political body or an order within the State”. The deputy Adrien Duport (or Du Port) proposed a decree on political equality, adopted on 27 September 1791. It provided that, like all citizens, Jews could enjoy civic rights as long as they took the “civic oath”.

However, a question arose: could Jews obtain civic rights if they retained their laws and customs, i.e. if they remained subject to the rules of Judaism? An amendment was adopted the very next day, providing that “the taking of the civic oath by Jews shall be regarded as a formal renunciation of the civil and political laws to which Jewish individuals believe themselves to be particularly subject”. This wording was deemed too radical, as it implied that Jews had to renounce their religion. A more moderate version was approved, which simply stated that the oath “shall be regarded as a renunciation of all privileges and exemptions previously introduced in their favour”.

It was Napoleon who took the logic of making citizenship and lifestyle coincide to its logical conclusion. At the end of the “Grand Sanhedrin” (meeting of rabbis) that he organised in 1806, he called on the Jews to renounce certain practices such as polygamy, repudiation and mixed marriages. He also required them to adopt French names and surnames on pain of expulsion (decree of 20 July 1808) and to show loyalty to France (the decree of 17 March 1808 instructed rabbis to remind them “in all circumstances to obey the laws”, particularly those “relating to the defence of the homeland”). This forced assimilation was a success. In the nineteenth century, Jews integrated into French society, to the point of providing several great republican figures or Juifs d’État who made careers in high administration, the arts or teaching in the service of republican ideals.38

“I don’t have a drop of French blood, but France runs through my veins”, said the writer Romain Gary, a Jew of Russian origin who became a naturalised French citizen in 1935. Assimilation was incorporated into the law from the 1930s, at a time when the country was experiencing a major wave of immigration. It is mentioned twice in the Ordinance of 19 October 1945, firstly in relation to the naturalisation procedure, which requires “assimilation into the French community” (article 69), and then in relation to people born in France to parents born abroad, who become French at the age of majority unless they show a “lack of assimilation” (article 46). The Ordinance of October 1945, now incorporated into the Civil Code (article 21-24), states that “no one may be naturalised unless they can prove that they are assimilated into the French community, in particular through sufficient knowledge, depending on their status, of the French language”.39 In June 2011, the legislature expanded this phrase by adding knowledge of “the French language, history, culture and society”. A 2003 law also extended the criteria for failure to assimilate to non-linguistic criteria, and provides that naturalisation after four years of marriage may be refused in the event of failure to assimilate (a 2006 law introduced polygamy as one of the criteria for failure to assimilate).

Assimilation meant restricting certain individual freedoms, for example in the choice of a child’s first name. The francization of Jewish names, instigated by Napoleon, merely generalised a policy that had been put in place for the population as a whole (law of 11 germinal year XI of the Republic, 1st April 1803) until it was abandoned in January 1993. The law of 25 October 1972 “relating to the francization of surnames and forenames” still provided that “any person acquiring or recovering French nationality may request the francization of their surname alone, their surname and first names or one of them, when their appearance, sound or foreign character may hinder their integration into the French community”. Faced with a large influx of immigrants from the Maghreb, it was agreed that the best way to avoid discrimination was to adopt French names.

Assimilation, which is egalitarian by nature, aims to make newcomers go unnoticed. In other words, it renders them invisible. It is the quid pro quo for high levels of immigration: while not everyone is born French, everyone can become French. Assimilation is optimistic: it is based on confidence in the institutions. If the droit du sol was introduced in 1889, shortly after the Ferry laws, it was because schools guaranteed that children who had lived in France would undergo an effective acculturation process.

Unfavourable Conditions For Racialism

Although the anthropological and cultural fabric of France has proven particularly hostile to racialism, history was not preordained. Another path was possible. At two points, France could have tipped over into a racial logic: during the slave trade and during colonisation. But this was not the case, both because the conditions did not lend themselves to it, and because the forces working in the opposite direction weighed more heavily.

The Slave Trade and the Failure of Racialism

Jean-Frédéric Schaub and Silvia Sebastiani, Race et histoire dans les sociétés occidentales (XV-XVIIe siècle), Albin Michel, Bibliothèque Histoire, 2021.

The slave trade has played an important role in the history of the West, but it has not undermined the anti-racial foundations of French society.

It could have been otherwise, as shown by the changes in the title of the Code noir. Initially, the royal edict of 1685 on slavery did not mention skin colour. Its original title was “Royal Edict concerning the policing of the French American islands”. The aim of this text was to regulate a status, not a race. It wasn’t until the 1720s that the expression Code noir became more widespread, and the term “Negro slave” made its appearance.40

The African kingdoms bear a crushing responsibility for the racialisation of slavery. By agreeing to sell Africans to Europeans in order to enrich themselves, these kingdoms established a tie between a status (slavery) and a skin colour, thereby creating the conditions for modern racism. The consequences were disastrous for Black people. It is not racism that created slavery, but rather the slavery of Africans that created racism.41

Despite everything, France managed to avoid racialism. Neither the Code noir nor any of the subsequent texts defined slavery in terms of race. Black men were not necessarily slaves: they could have been freed or born free. Blacks and people of mixed race could leave their slave status, in particular through marriage. The “free people of colour” were certainly subject to major restrictions, but their situation must be judged in the light of a society that was not egalitarian. What’s more, they were able to become wealthy and own slaves themselves. Toussaint Louverture, who led the revolt in Santo Domingo, owned around twenty slaves on the eve of the French Revolution. His case is far from isolated: according to an inventory drawn up by the CNRS, 30% of the slave owners compensated in 1825 and 1849 were themselves former slaves – sometimes, it is true, to buy back members of their family.42

There are two signs that racialist temptation existed in France. The first concerns interracial marriages, which were banned at the end of the Ancien Régime with the ruling of the King’s Council of State on 5 April 1778. This ruling temporarily put an end to a practice that had been developing since an edict of 1716 had authorised masters to come to France with their slaves, leading to an increase in the Black population and mixed marriages. Taking care of a Black child was even fashionable among aristocrats: Madame du Barry, the famous mistress of Louis XV, took a Black child, Zamor, under her protection, who was to be her undoing when he denounced her to the revolutionary court.

The second sign was Napoleon’s reintroduction of slavery in 1802. It is generally accepted that the emperor was neither a racist nor a slaver, but a pragmatist. His to re-establish slavery was linked to international circumstances and in reaction to the betrayal of Toussaint Louverture, who had established a local tyranny and aspired to secede from France. But other measures adopted by Napoleon had a distinctly more racialist slant: the ban on Black servicemen coming to Paris (May 1802), the ban on the presence of Black people in metropolitan France (June 1802) and the prohibition of interracial marriages (January 1803).

However, these racialist measures remained ad hoc and limited. The ban on interracial marriages disappeared in 1848 along with the abolition of slavery in the colonies. It did not have the same history as in the United States, where prohibition of such unions began in the eighteenth century and lasted until a Supreme Court decision in 1967, and even beyond for some states.

The absence of a Black population in metropolitan France certainly contributed to this failure of racialism. France was a latecomer to the slave trade and, unlike other countries, did not bring slaves back to its territory where slavery was prohibited. As a result, the issue of race remained peripheral: it never played a structuring role in social and economic life, so it did not give rise to legal codification or the creation of powerful interest groups.

The Absence of Racialism during Colonisation

Eugen Weber, La Fin des terroirs : la modernisation de la France rurale : 1870-1914, Fayard, 1983.

Rabaut de Saint-Étienne, Réflexions sur la nouvelle division du royaume, 1790.

Arthur Girault, Principes de colonisation et de législation coloniale, 1894.

Speech to the Chamber of Deputies, 28 July 1885.

Yerri Urban, Race et nationalité dans le droit colonial français (1865-1955), Université de Bourgogne, public law thesis, June 2009.

The law of 28 June 1881, often presented as the « code de l’indigénat », was in no way a code: It was in fact a very short text (three articles) which merely transferred the repression of indigenous people to the administrative authorities for the mixed communes.

Julien de Lasalle, « Étude sur le régime disciplinaire en Algérie : les répressions militaires, les commissions disciplinaires et l’indigénat », Bulletin de la société de législation comparée, 1889 [online].

Emmanuelle Saada, « Nationalité et citoyenneté en situation coloniale et post-coloniale », Pouvoirs, vol. 160, n°1, 2017, pp.113-124 [online].

Benoît De L’Estoile, Le goût des autres : de l’Exposition coloniale aux Arts premiers, Flammarion, 2007.

After the slave trade, the second moment when racialism could have taken hold was colonisation. But here again, the conditions did not lend themselves to it. The first colonial empire, which ended in 1763, was too superficial and short-lived to leave any lasting traces. As for the second wave of colonisation, it essentially took place under the Third Republic, at a time when equality was celebrated.

Colonisation was not the result of a pre-planned project, but rather of rivalries between the European powers. Above all, it was not a block – neither homogenous in space nor stable over time, it covered different and evolving realities.

In managing its empire, the Republic was torn between two approaches: assimilationism and differentiationism. Assimilationism adopted the objectives of the policy pursued in metropolitan France with regard to the provinces – sometimes compared to colonisation.43 “There are no longer various nations in the kingdom; there is only one (…); there are no longer Bretons, Provençaux, Languedociens, there are only French”, said Rabaut de Saint-Etienne during the Revolution to justify the creation of the départements. 44 A century later, the same logic was applied to the colonies. In his 1894 book Principes de colonisation et de législation coloniale (Principles of colonisation and colonial legislation), Arthur Girault defined assimilation as “a closer union between colonial territory and metropolitan territory” with the aim of creating new French départements.45

Colonisation was certainly a response to political and economic objectives, but it was also intended to bring “equality, freedom and independence to the inferior races”, in the words of Jules Ferry.46 This moral justification, reminiscent of the argument put forward by Sepulveda in the sixteenth century in support of the conquest of India, was endorsed by the great figures of the nineteenth century such as Tocqueville and Hugo, who considered that colonisation was justified by the fight against slavery, which was abolished in all the territories conquered by France.

The term “race” used by Ferry is offensive today, but it is used in a cultural rather than biological sense, otherwise its use would be inconsistent with the desire to transform the mentality of the colonised peoples. No irreducible barrier is envisaged here: the aim is to bring civilisation to the colonised peoples, not to create a segregationist system. The desire to teach “Our Ancestors the Gauls” throughout the empire, which became a subject of mockery after decolonisation, represents the very opposite of a racial conception: by symbolically proclaiming that there is a common ancestry, the aim is to materialise an assimilationist optimism that has freed itself from genealogies.47

However, the implementation of this assimilationist ideal was complex. It came up against various obstacles: local cultures, the diversity of situations, economic interests, the risk of revolt, pressure from the colonists – all factors that gave rise to various legal adjustments, criticised at the time in the name of republican principles.48

In Algeria in particular, the sénatus-consulte of 1865, bequeathed by the Second Empire, provided for Muslims and Jews to remain under their own personal status. This differentiation had less to do with racial logic than with cultural concerns: from the point of view of Napoleon III’s “Arab kingdom”, it was a question of respecting Islamic and Judaic cultures, in line with the recommendations of the Saint-Simonians, the avant-garde theorists of multiculturalism. What’s more, Muslims and Jews had the option of changing their status. While the Jews collectively demanded naturalisation (which they obtained in 1870 with the Crémieux decree), the Muslims preferred to retain their Islamic legislation.

The notorious Code de l’indigénat (Indigenous Code), which is so much decried today even though it never existed, was simply a set of high-level police rules designed to manage the conquered territories where there had been several revolts.49 Conceived as a temporary measure initially managed by the army, this code very quickly aroused the unease of the public authorities, who saw it as a “legal monstrosity”.50 It was therefore gradually scaled back before being abandoned in the aftermath of the First World War.

In the French colonial empire, although the natives were subjects (they had French nationality but no civil rights), they did not lack political rights. The stumbling block was less to do with race than with culture: could citizenship be granted to populations who were governed by their personal status? In other words, could one be a French citizen while being subject to rules other than those of the Civil Code? In the case of Algeria, the answer was no: to become a citizen, it was necessary to renounce Koranic law. But in other cases, the answer was yes, as in Senegal and India.51 In Tahiti, the annexation treaty of 1880 granted full citizenship to the inhabitants – at least to those who spoke French.

Nothing expresses these republican divisions better than the 1931 Colonial Exhibition. This event, organised by Marshal Lyautey, is now considered to be a “human zoo”, which is a misunderstanding because its purpose was, on the contrary, to honor the colonised populations in order to better exalt the greatness of France. The confusion stems from the fact that, at the same time as the Colonial Exhibition, a private initiative led to the installation of a “Kanak village” in the Jardin d’Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne. This event, which portrayed the Kanaks as cannibals, was denounced at the time. Lyautey retired the governor of New Caledonia who had helped with the event. In reality, the Colonial Exhibition staged three types of narrative that ultimately ran through the history of colonisation, none of which are racialist in nature: primitivism, evolutionism and differentialism.52 Primitivism extends the ideal of the good savage living in harmony with nature; evolutionism is based on an optimistic vision of progress, which extends the assimilationist ideal; and differentialism celebrates the diversity of cultures. In their own way, these three narratives testify to a genuine respect for the “taste of others”, of which the Musée de l’Homme (1937) and, later, the Musée du Quai-Branly (2006) are concrete manifestations.

The Rejection of Race in Scholarly Discourse

“If we were to suppose them to be men, we would begin to believe that we ourselves are not Christians” in Montesquieu’s , « De l’esclavage des nègres », De l’Esprit des lois, XV-5, 1748.

Diderot, Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, Gallimard, Folio Classique, 2002 [1776].

One of the works most favourable to slavery is a reaction to this idealisation: it is the book by Louis-Narcisse Baudry des Lozières, a slave-owning aristocrat from Santo Domingo, entitled Les égaremens du nigrophilisme (Paris, Migneret, 1802). The author starts from the observation that slavery “is a monster in the eyes of part of Europe”, but sets out to demonstrate its validity by explaining that, on the one hand, the colonies have become indispensable to Europeans and, on the other, that Europeans are not capable of working in these latitudes to produce what they need. Cynically, he added that being a slave was a lesser evil compared to living conditions in Africa where, he said, the local tyrants made Robespierre look like an amateur. He even concludes that the slave trade is an expression of humanitarian compassion.

Claude Rétat, « Jules Michelet, l’idéologie du vivant », Romantisme, vol. 130, no. 4, 2005, pp. 9-22.

Sylvain Venayre, « Le mythe de l’origine chez les historiens français du xixe siècle », in Les historiens croient-ils aux mythes ? Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2016.

His book Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines (1853-1855) had very little impact in France, where only a few dozen copies were sold.

Tocqueville wrote to Gobineau on 14 January 1857: “Christianity has obviously tended to make all men brothers and equals (…). Be sure, I say, that the bulk of Christians in the world cannot feel the slightest sympathy for your doctrines”, in « Correspondance entre Alexis de Tocqueville et Arthur de Gobineau », Revue des Deux mondes, volume 40, 1907 [online].

Jean-Marc Bernardini, Le darwinisme social en France (1859-1918) : fascination et rejet d’une idéologie. CNRS Éditions, 1997 [online].

Daniel J. Kevles (Daniel J.), Au nom de l’eugénisme : génétique et politique dans le monde anglo-saxon, PUF, 1995.

Carole Reynaud-Paligot, L’école aux colonies. Entre mission civilisatrice et racialisation 1816-1940, Champ Vallon, La chose publique, 2020.

Jean-Claude Wartelle, « La Société d’Anthropologie de Paris de 1859 à 1920 », Revue d’Histoire des Sciences Humaines, vol. 10, n°1, 2004, pp.125-171.

Jean-Marie Guyau, Education et Hérédité: étude sociologique, Paris, Félix Alcan, 1889.

Laurent Cordonier, La nature du social : l’apport ignoré des sciences cognitives, PUF, 2018; Bernard Lahire, Les structures fondamentales des sociétés humaines, La Découverte, 2023.

In Moscow, the Romanov obelisk, hijacked by the Bolsheviks to pay tribute to socialist thinkers, features a number of French authors.

One of the best proofs of the failure of racialism lies in the attitude of the learned elite. Indeed, the French intellectual tradition has rarely made race an explanatory factor. When Montesquieu reflected on the predispositions of peoples towards freedom, with the aim of understanding why a “genius for liberty” or, on the contrary, a “spirit of servitude” is formed, he deferred to the role of climate and used irony to denounce slave owners who refused to consider “Negroes” as men in their own right.53

Montesquieu’s thesis on climate was widely debated. Approved by Rousseau, contested by Voltaire for its reductive nature, it gave rise to lengthy debates right up to the 21st century, but one thing is certain: it has never been replaced by a racialist explanation.

Yet a theory of race could have found its place in the Age of Enlightenment. With the criticism of Christianity and the idealisation of science, a breeding ground existed. The discovery of morphologically highly typified peoples could have led scholarly discourse towards the polygenist thesis as a reaction to the Adamic vision of the unity of the human species, as would happen a century later with Paul Broca and the Paris Anthropological Society.

But political and religious confrontations closed the door on this option. Far from being despised, primitive peoples provided a solid argument for supporters of the social contract to denounce absolutism and Christianity. Diderot’s Tahitian came at the right time: it allowed the creation of a positive imagination of the state of nature and provided empirical support for the thesis that other forms of social organisation are possible.54

In short, the idealisation of the Other was proportional to the criticism of monarchist and Christian society: if primitive peoples were valued, it was the better to denounce the vices of Ancien Régime society.55 Reflections on the social contract acted as a shield: the figure of the primitive, supposed to embody humanity in its original state of innocence and purity, provided living proof that institutions are no more than social conventions, which left little room for a depreciatory vision of savage peoples.

Subsequently, a large part of French thought ignored race. The great explanatory theories of history were careful not to refer to it. Although the Germanist theory of the origins of France was revived in the nineteenth century by Augustin Thierry, who proposed to interpret the French Revolution as the revenge of the conquered race (the Gauls) on the conquering race (the Franks), it was rejected by contemporaries such as Jules Michelet and, later, by Fustel de Coulanges. 56 Out of anti-Germanism after the defeat of 1870, the latter could not conceive of the French nation being indebted to the Franks, and therefore to the Germans.57

Racial theories have remained peripheral to intellectual life. It would be hard to name a genuine theorist of race, apart from Arthur de Gobineau. But he remained marginal.58 As a sign of his failure, his thesis on decadence through racial miscegenation was rejected by his friend and mentor Alexis de Tocqueville, also an aristocrat, who dismissed Gobineau in the name of the Christian message of human equality.59

It is no coincidence that it was in France that the theory of the heredity of acquired traits emerged, conceived by Lamarck shortly after the French Revolution. A faithful reader of Rousseau, Lamarck put forward a theory of evolution based on a very flexible conception of living organisms, giving pride of place to mutations in organisms under the influence of the environment. Neo-Lamarckism was to have a lasting influence on the French elite, to the point of preventing the emergence of Social Darwinism, which was based on a concept of living beings that was not very malleable.

Social Darwinism, like racialism, has never managed to penetrate the French elites and intellectuals, no doubt also because of a profound reluctance to embrace liberal ideas in a country that sanctifies the role of the state.60 This explains the failure of eugenics policies, which flourished in Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian countries, where they were actively implemented.61 Even the Vichy regime stuck to a classically natalist approach (family allowances, births under X) despite the efforts of Alexis Carrel, one of the few promoters of eugenics in France, whose only success was to introduce modest marriage certificates. At no time did French governments implement forced sterilisation policies.

It is true that a physical anthropology emerged in the nineteenth century, characterised by the study of human races in the context of colonisation in Africa, but its importance should not be exaggerated. The Paris Anthropological Society, founded in 1860 by Paul Broca, a freethinker and brilliant scientist, certainly set out to demonstrate the diversity of racial and sexual aptitudes using cranial measurements, but this school was devoid of any political influence, particularly in the colonies, even if the racial factor was put forward to explain the difficulties encountered by the Republic in its educational ambitions.62

Racialist science was soon marginalised. Its heyday was in the 1880s and 1890s, until the social sciences took off and became institutionalised. Its only disciple was Vacher de Lapouge, the rare outspoken supporter of eugenics in France and a committed socialist activist.63 Even Gustave Le Bon only remembered Broca for his craniometry of women, preferring a cultural interpretation to explain the differences between civilisations.

At the end of the nineteenth century, French sociology completely rejected race and, more generally, biology and heredity. Emile Durkheim made it clear: the social had to be explained by the social. To demonstrate the relevance of this science of the social, which he championed, he took care to refute race as a cause of suicide. Before him, someone like Jean-Marie Guyau, son of Augustine Tuillerie (pseudonym of G. Bruno, the author of Tour de la France par deux enfants) and son-in-law of Alfred Fouillée, had set out to put the theories of heredity into perspective.64 Authors such as Marcel Mauss and Arnold Van Gennep, convinced of the fundamental unity of the human race, turned away from racial anthropology and developed a strictly social ethnology.

Since then, the social sciences have always given precedence to social factors over ethnic or racial origins, as well as overall biological criteria, even if this sometimes means going too far in the opposite direction by totally neglecting nature, as Laurent Cordonier and Bernard Lahire have recently pointed out.65

This prevalence of the social is confirmed by one clue: while a great many French intellectuals subscribed to the communist ideology, they made no contribution whatsoever to the National Socialist ideology.66 The only author who could have had an influence was Gobineau, but he believed that the decadence of the races as a result of miscegenation was too far advanced to make a return to the state of original purity possible. Worse still, as he did not clearly rank the races, and even tended to praise the Jews – whom he classified as part of the White race – he was deemed unattractive by the Nazis. In France, no intellectual advocated the extermination of African populations, as Pastor Paul Rohrbach did

in Germany, helping to justify the first genocide of the 21st century with the massacre of the Hereros in Namibia.

The Political Sources of Anti-Racism

Maurice Barrès, Les diverses familles spirituelles de la France, Emile-Paul Frères Editeurs, 1917. Even Vichy preserved Jewish veterans by giving them a special place in the October 1940 statute (see article 3).

Jacques Bainville, Histoire de France, 1924.

Paul Yonnet, Voyage au centre du malaise français. L’antiracisme et le roman national, Gallimard, 1993.

Antoine Math, « À la croisée d’enjeux nationaux et internationaux : la protection sociale des personnes étrangères ressortissantes d’un pays non-membre de l’Union européenne », Informations sociales, vol. 203-204, n°2-3, 2021, pp.158-166 [online].

However, a law passed in 2008 corrected this potentially devastating anomaly by reiterating that discrimination on the basis of nationality is legitimate for access to the civil service.

« Sans distinction de … race », Mots. Les langages du politique, n°33, December 1992. This proposal was relaunched in 2018, with no further success despite a favourable vote by the National Assembly. See, « L’Assemblée supprime de la Constitution le mot ‘race’ et interdit la ‘distinction de sexe’ », Le Monde, 12 July 2018 [online].

The establishment of the Third Republic dealt a further blow to racialism: not only were racial theories found to be incompatible with civic equality, but race and heredity were also rejected because of their link with the Ancien Régime monarchy.

The royalist movement itself hardly took up the theme of race, and neither did the nationalist camp: Germanophobia resulting from the defeat of 1870 and the war of 1914-1918 prevented it from doing so. Maurice Barrès’s reversal on antisemitism is telling: the war was not yet over when he celebrated the commitment of the “various spiritual families” to the defence of the homeland, including the Jews.67 Even Xavier Vallat, the future commissioner for Jewish issues under Vichy, was not indifferent to the fraternity of arms. After declaring to the Chamber in June 1936, in reference to Léon Blum, that “for the first time, this old Gallo-Roman country will be governed by a Jew”, he took pains to reject the accusation of antisemitism by adding: “I do not intend to forget the friendship that binds me to my Israelite brothers in arms”.

The fraternity of the trenches left deep traces, as did hatred of the Germans. For Charles Maurras, Germanophobia acted as a vaccine against racialism. Rejecting Gobineau, he linked racism and antisemitism to German whims.68 “We are nationalists. We are not German nationalists. We have no doctrine in common with them. Any falsification, any abuseof texts can be attempted: we will not be turned into racists or gobinists. We don’t believe in the nonsense of racism”. For his part, the historian Jacques Bainville, a republican who had become a royalist in the service of Action Française, declared shortly after the 1914 war that “The French people is a composite. It is more than a race. It is a nation”.69

The war of 1940 completed the discrediting of race, as much political as scientific. Anti-racism became a “civilisational rock”: established as an international standard, it was backed by governmental and non-governmental organisations.70 It was as part of a campaign organised by UNESCO that Claude Lévi-Strauss presented his lecture “Race and History” in 1952.

In France, the post-war rejection of race owes much to the Shoah, but it also owes much to the colonial question. The war had weakened the legitimacy of the European powers. Rights had to be granted to the colonies. The 1946 Constitution states that “the French people once again proclaim that every human being, regardless of race, religion or creed, possesses inalienable and sacred rights”.

The creation of the French Union states that “France shall form with the overseas peoples a Union based on equality of rights and duties, without distinction of race or religion”.

Other factors worked against race. The introduction of compulsory social security in 1945, by redefining individual rights on the basis of work and production, brought foreigners more closely into the national community. A movement began to take shape in favor of aligning the rights of foreigners with those of nationals – an alignment that, already longstanding, would continue to deepen. Anti-Americanism adds another layer. In the same way that Germanophobia discredited antisemitism, anti-Americanism – so prevalent in post-1945 France – discredits racism, which is seen as the attitude of a crude nation, unable to rise above physical differences move beyond its slave-owning past. This feeling of superiority was confirmed in a French television report in April 1964 featuring four prominent African Americans: singers Nancy Holloway and Hazel Scoot, photographer Emil Cadoo and writer William Gardner Smith. All four chose to live in France because, according to their own statements, there was no racism.71 The tone of the report is one of national pride: they are proud that France is not as racist as the United States. The report closes with praise for assimilation: against a backdrop of images of Black people in suits and ties, the commentator boasts that Americans have been “conquered by the baguette de pain and the paquet de Gauloises”.

With the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989-1991, an era of peace seemed to be dawning. The enemy disappeared. The overcoming of borders, already largely initiated by the construction of Europe and the GATT, seemed within reach. The Maastricht Treaty adopted in 1992, the Internet launched in 1993, and the WTO set up in 1994 were all signs of optimism. A peaceful world, governed by universal human rights, was becoming the horizon for new generations.

Today, nationality is ceasing to be a legitimate criterion of distinction. The “privilege of the national” is finally being erased when it comes to access to social rights.72 “National preference”, which had previously been taken for granted, is becoming synonymous with exclusion and is seeing itself being associated with racism. Xenophobia itself is becoming confused with racism. Any differentiation in treatment between nationals and foreigners is becoming suspect. The civil service has opened to European foreigners (1991) and the new Criminal Code (1994) now includes nationality among the prohibited criteria for discrimination.73 European foreigners can now vote in local and European elections.

The very word “race”, already lacking legitimacy, is now even more strongly rejected: its use requires great caution in language. The first controversy erupted in 1992: does the word still have a place in legal texts, particularly in the Constitution?74 Because it is accused of fostering racism, the word has been called to disappear from the Constitution – even though it is used there as a safeguard against racism.

No comments.