The myth of a racist France (2)

From the failure of racialism to the birth of the mythAnti-racism as a social norm

An Open Population

Diversity as an Ideal

Acts of Racist Violence

Proof from Aya Cissoko?

Structural anti-racism

Race in the United States

The Invisibility of Origins

The Visibility of the Invisible

The Myth Of Structural Racism

On the Origin of Myths

Instrumentalization

Over-Interpretation

Reductionism

Blindness

Conclusion

Summary

Having highlighted, in the first volume of this study, the factors that have kept France at a distance from the ideology of race, we now turn our attention to the – very concrete – evidence that French society is characterised by a structural hostility to racism and racialism. A comparison with the United States, a country that is similar in many respects, helps to highlight the divergence in trajectories between the two countries.

As well as criticising the systemic racism thesis, we need to understand why such a thesis has been able to emerge and enjoy relative success. To do this, a diversion into mythology is necessary. Situating systemic racism within the context of myth allows us to understand its intellectual underpinnings and to grasp the risks that this theory entails, particularly in a time of heightened tensions around immigration and the role of minorities.

Vincent Tournier,

Senior lecturer in political science, Grenoble Institute of Political Studies.

Anti-racism as a social norm

Identifying norms is an important step in sociological analysis: it enables us to distinguish the rule from the exception, the essential from the incidental. There are, for example, road accidents, but these reamin rare when considered in relation to the number of drivers; the norm therefore lies in cautious, law-abiding driving that, even if reckless drivers do exist.

Proponents of structural or systemic racism never approach the problem from this angle. They themselves are careful not to say why they have managed to escape a norm that is supposed to be so pervasive. But the question is essential: what is the norm? Not asking this question means that we do not have to prove the existence of a racist norm, and we do not have to explain its origins.

Yet all evidence suggests that, in France, the norm has developed in opposition to racialism. Built up over the long term, this anti-racist norm was further consolidated after 1945. Long prevalent among the elites, it also prevails among the French population, whose ethos (or basic personality, to use the term of the anthropologist Abram Kardiner) is marked by strong anti-racism.

An Open Population

Jean Raspail’s book, rediscovered in the 2010s when some saw in it a premonitory reflection. See Jean Raspail, Le Camp des Saints, Robert Laffont, 1973.

Hubertine Auclert, Le vote des femmes, V. Giard & E. Brière, 1908, chapter « Les femmes sont les nègres ».

Ilyès Zouari, « Le droit de vote pour les ultramarins: une exception et une fierté françaises », Causeur, 14 January 2022 [online].

Didier Rykner, « ‘Au Nègre Joyeux’ n’est pas une enseigne raciste », La Tribune de l’art, 18 November 2017 [online].

Benjamin Doizelet, « L’intégration des soldats noirs américains de la 93e division d’infanterie dans l’armée française en 1918 », Revue historique des armées, n°265, 2011 [online].

Since 1971, there has also been a Maison de la Négritude et des Droits de l’Homme in Champagney (Haute-Saône). Through this modest institution, which owes its name to Léopold Senghor who came to give it his patronage, the inhabitants wanted to commemorate the astonishing gesture of their ancestors who, in in article 29 of their cahier de doléances dated 19 March 1789, called for the abolition of Black slavery [online]. During the Revolution, some 70 people in the depths of France said that “the inhabitants and community of Champagney cannot think of the evils suffered by the Negroes in the colonies without their hearts being filled with the deepest sorrow as they imagine their Peers, still united to them by the double bond of religion, being treated more harshly than beasts of burden” [online].

Daniel Derivois, « Pour lutter contre le racisme, mieux comprendre le mot ‘nègre’ », The Conversation, 21 February 2023 [online].

To regard France as a structurally racist country seems inconsistent with the presence of a long-standing and significant immigrant population. Admittedly, immigration is driven by economic considerations, but it reached such proportions without a relatively open context. This helps to explain, for instance, how a large Algerian population was able to settle in France after decolonisation, even though the legacy of the Algerian war could have led to much more frequent violence than what actually occurred.

Contrary to popular belief, the French population has not exhibited widespread racist or exclusionary attitudes. Until the 1980s, the far right never achieved significant electoral breakthroughs. While xenophobia may have influenced a part of the electorate at various times – particularly during periods of economic difficulty – it never translated into votes.

Even during periods of high immigration, the fear of demographic submersion remained limited, likely outweighed by a strong confidence in the country’s ability to assimilate, thanks to its schools, military service and prosperous economy.1 Another factor that played part may have been the feeling that the elites were committed to protecting the population, as evidenced by the long lists of the dead engraved on the walls of the Grandes Écoles.

Numerous factors, presented in the rest of this text in a series of concrete examples, testify to the broad openness of the French population. France granted the right to vote to Black people and Arabs before granting it to French women. This anteriority provoked the anger of the feminist Hubertine Auclert, who wondered how it was possible to give priority to “savage Negroes over cultivated White women”.2 Even today, residents of the overseas territories are considered to be full citizens, since they vote in national elections, which is not the case in the United States or Great Britain, where overseas populations are not allowed to take part in national elections.3

The Black man has never been a repulsive figure, quite the contrary. An indicator is provided by an old advertisement for Banania cocoa powder with the slogan « Y’a bon, Banania » (“Yum, Banania”). First appearing in 1914, this slogan was displayed alongside the joyful face of a Senegalese rifleman, identifiable by his red headgear, the chéchia, a traditional male headdress worn in some Muslim countries.

A controversy arose in 2005 when Banania wanted to reintroduce this design in a stylised form. Accusations of racism were immediately made by the MRAP (Mouvement contre le racisme et pour l’amitié entre les peuples – Movement against Racism and for Friendship between Peoples) and an overseas group and the drawing was withdrawn.4 But was it racist? The text on the box read “Family breakfast”. It is inconceivable that the promotion of a product aimed at children could be based on a frightening or despicable character: if this rifleman was chosen, it was because he embodied a warm and sympathetic figure, no doubt even a protective one.

Polarisation on the supposed racism of French society leads to a series of misunderstandings. A case in point is the controversy surrounding the sign of a former Parisian café called « Au Nègre Joyeux » (“The Happy Negro”), which features an 1897 painting of a Black man and a White woman. Anti-racist activists interpreted the painting as a White bourgeois woman being served by a Black slave, when in fact it was the opposite: a White maid serving a tray to a Black man dressed as a gentleman.5

During the First World War, American authorities were concerned that Black soldiers, after experiencing a non-segregationist country, would develop ideas of liberty and equality.6

In the interwar period, the music brought by Black marching bands captivated audiences and contributed to the success of “Negro art”. At the time, this adjective carried no derogatory connation, as the writer Aimé Césaire turned it into a badge of pride by celebrating his négritude. It was even in the company of Léopold Sédar Senghor and Léon Gontran Damas, all three of whom were to become members of parliament, that in 1935 Césaire founded the magazine L’Étudiant noir (The Black pupil), which was at the origin of the négritude movement.7 The fact that the term nègre was taken up so readily by these figures was a sign that it did not have the same contemptuous connotation as “Negro” in the United States.8

When Joséphine Baker, the mixed-race American dancer, arrived in France in 1925 – where she would triumph with the Revue Nègre before becoming the star of the Folies Bergères – she said she was struck by the absence of racial segregation: “I was suffocating in the United States (…). I felt liberated in Paris”. In her memoirs, she was highly critical of the situation in North America, before confessing: “France made me who I am, beyond all prejudice”. Celebrated by many artists who were passionate about Negro art, she became a French citizen in 1937. After taking part in the Résistance, she devoted the rest of her life in France to humanitarian work.

This testimony is similar to that of the academic Pap Ndiaye who, before becoming Minister of Education, said he had never encountered racism in his youth, albeit having lived in a White environment. “We weren’t exposed to these issues”, confirmed his sister Marie. He himself admits that he only “discovered the Black world” once in the United States, where he obtained a university scholarship thanks to an Affirmative Action programme.9

Diversity as an Ideal

Gilles Gauvin, « L’affaire des enfants de la Creuse. Entre abus de mémoire et nécessité de l’histoire », 20 & 21. Revue d’histoire, vol. 143, n°3, 2019, p.85-98 [online].

Very few of these children (around 150) have come forward to seek compensation, see Patrick Roger, « “Enfant de la Creuse” : un rapport pointe la responsabilité de l’État », Le Monde, 10 April 2018 [online]. It is interesting to note that this affair, which provoked reactions that were each more dramatic than the last (the National Assembly passed a resolution in February 2014; the Minister for Overseas France set up a fact-finding mission entrusted to a sociologist in 2016; CRAN considered filing a complaint for crimes against humanity, etc.) has not been tempered by the concomitant debates on unaccompanied minors (UAMs), young children generally from the Maghreb, for whom the State and local authorities are this time being called upon to take charge of them despite the fact that they are far from their place of origin and, what’s more, despite the exorbitant cost.

Jean-François Mignot, L’adoption, La Découverte, 2017.

In the early 2000s, the “children of Creuse” affair hit the headlines. This was named after the children from l’île de la Réunion – most of whom had been abandoned – were placed in the child welfare system and sent to metropolitan France, mainly to the Creuse region. Launched by former Prime Minister Michel Debré – a deputy of la Réunion – this operation resulted in around 2,000 children being placed with families in mainland France between 1962 and 1984.10

Rediscovered years later, this affair gave rise to a terrible indictment of the French State, which was accused by the Association des Réunionnais de la Creuse of having organised a “deportation”. Yet there was nothing racist about this policy: neither the public authorities nor the inhabitants of Creuse saw racial difference as an insurmountable obstacle.11

In reality, two different conceptions of adoption clashed here: in la Réunion, as in some parts of the world (Sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania), adoption is part of the practice of confiage, which involves entrusting one’s children to other family members without severing the bond of parentage.12 This is not the case in France, where full adoption creates a true legal parent-child relationship.

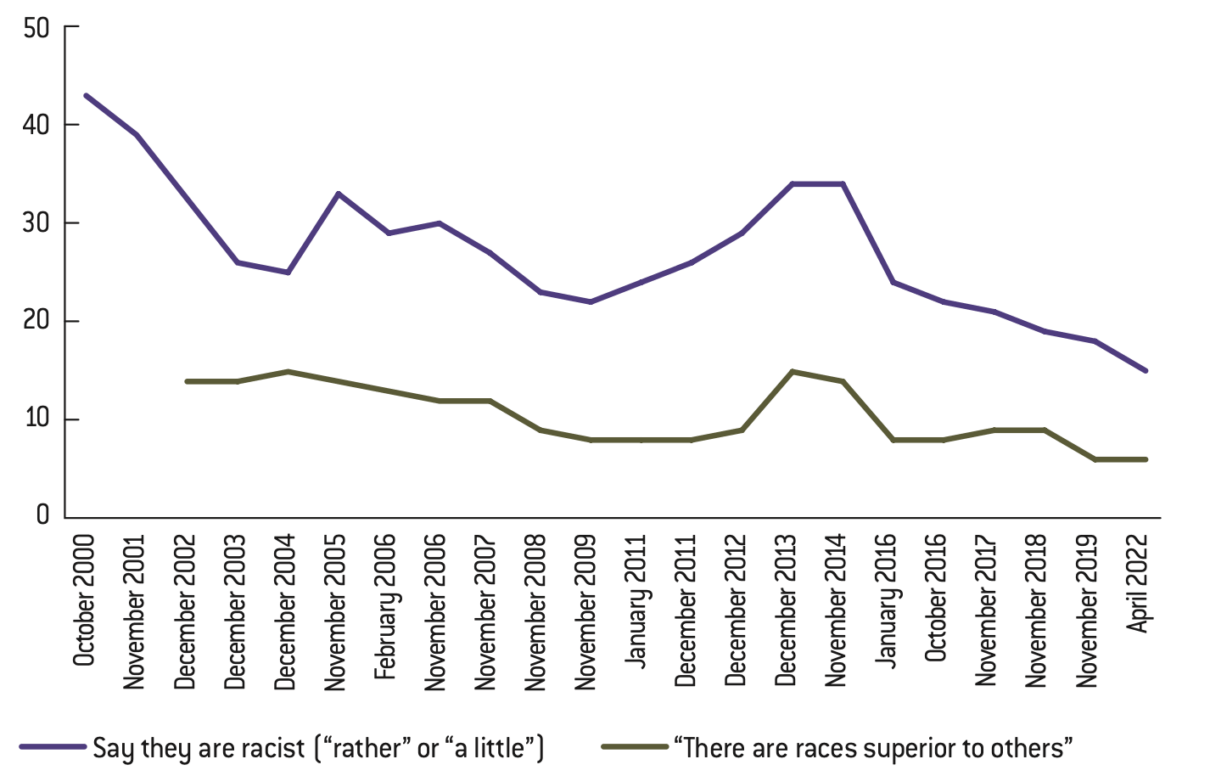

Figure 1: Overt Racism in France (2000-2022)

Source :

CNCDH (annual reports).

Although it is not easy to assess the degree of racism in a population, the data compiled by the Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme (the National Consultative Commission for Human Rights – CNCDH) since the early 2000s show that the proportion of the population who declare themselves to be racist is low, even when taking into account individuals claiming to be “a little” racist (Figure 1).

More significantly, the proportion of French people who think there are “superior races” is limited to 10%. For these two indicators, there is a downward trend, which is hardly compatible with the idea that society is structurally racist.

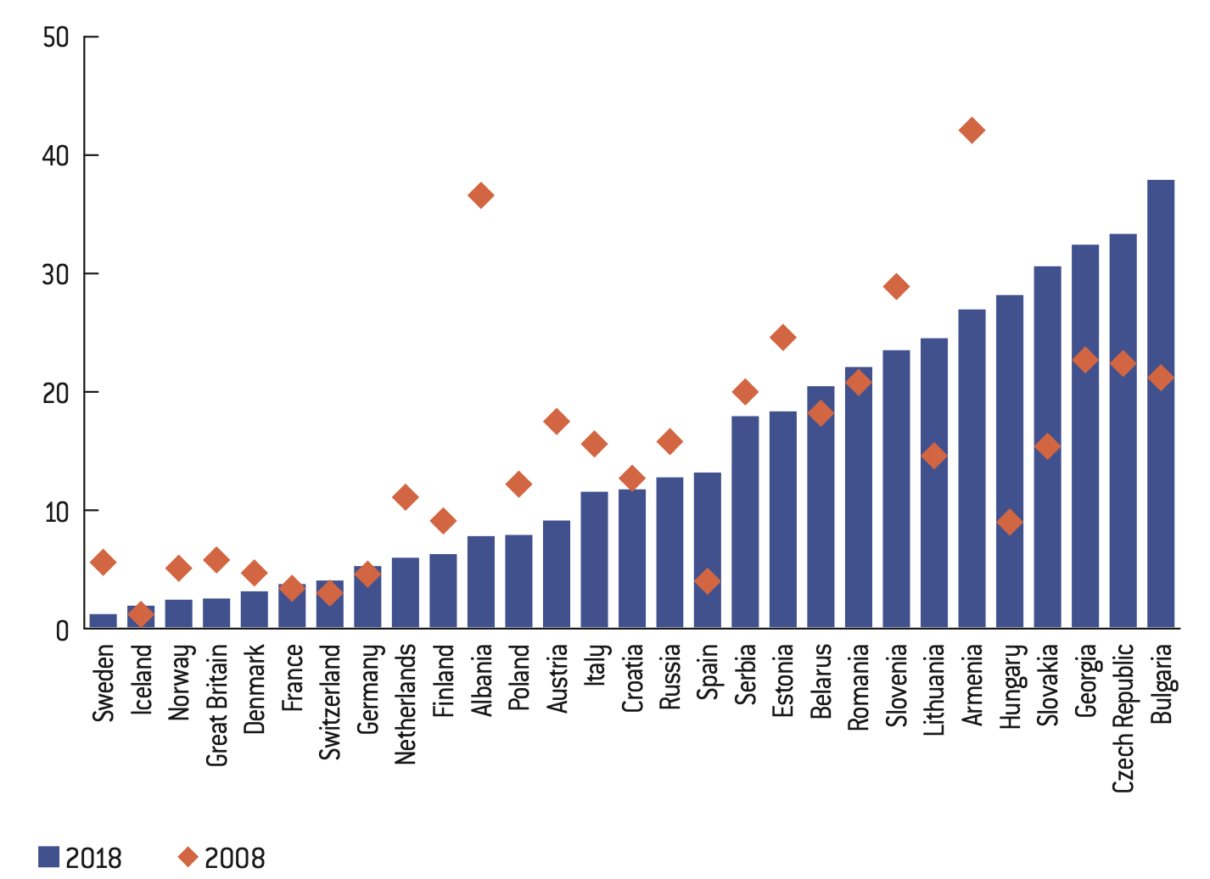

Figure 2: Percentage of individuals who cite “people of different races” as undesirable neighbours

Source :

European Values Survey (author’s calculations).

For more details, see Vincent Tournier, « Dis-moi qui tu ne veux pas pour voisin : les Européens et la tolérance », The Conversation, 25 February 2020 [online].

Jean Messiha, « Le métissage (mais pas n’importe lequel) : la nouvelle norme du progressisme », Causeur, 20 February 2020 [online]. See also Denis Bachelot, « De la représentation ethnique dans la publicité », Commentaire, n°188, Winter 2024 [online].

The traditional Polynesian pirogue (the vaa’a) has even been given a new lease of life in Brittany. See Malo Camus-Le Pape, « Relocalisation d’une activité sportive “traditionelle” : altération ou renforcement identitaire ? Le cas du va’a, la pirogue polynésienne, en Bretagne », Sciences sociales et sport, vol. 19, n°1, 2022 [online].

An even more significant indicator is knowing with whom one would refuse to live as a neighbour. According to surveys on the values of Europeans (Figure 2), few French people say they do not want immigrants as neighbours (13% in 1990, 9% in 2018) or people of a different race (9% in 1990, 4% in 2018). These figures are among the lowest in Europe. They are incomporable to the groups that provoke much more hostility, notably drug addicts (57% of the French do not want them as neighbours), alcoholics (41%) or Gypsies (23%).13

Interracial couples are often portrayed in advertisements and television programmes as an expression of a mixed diversity that aligns with the ideal of exogamous marriage. No one knows how common such couples are in real life, whose media presence is openly encouraged by Arcom, but the fact is that their presence on screens has become normalised without causing much outrage: no organised protests, no calls for boycotts accompany these advertisements in which anthropologists might see a sign of an open society that is willing to give its women. Few, like Jean Messiha, are surprised that the model often presented is limited to a Black man with a White woman, following a possibly sexist model.14

If we add to this the fact that people of colour regularly feature among the favourite personalities in France, or that the French have a strong taste for travel and world cultures, perhaps driven by hedonism but also by a sincere desire to discover and engage with what others are doing15 – so much so that they are accused of “cultural appropriation” – or the fact that French students are taught tolerance and respect from an early age, and that young people rank the fight against racism highly among their concerns, it is indeed difficult to detect systemic racism in French society.

Acts of Racist Violence

During his two-year trip to the United States, Richard LaPiere found that hotels and restaurants had no problem accommodating him and a couple of Chinese friends. After his trip, he wrote to 250 establishments (including those he had visited) to ask them if they accepted Chinese people, who were victims of anti-Chinese legislation at the time. More than 90% of the establishments replied in the negative, which led LaPiere to say that it is important to distinguish between prejudice and action. See Richard LaPiere, “Attitudes vs. Actions”, Social Forces, vol. 13, n°2, 1934.

Stéphane Mourlane, « Les anarchistes italiens dans les Alpes-Maritimes et le Var à la fin du xixe siècle : le choix de la marginalité ? », Cahiers de la Méditerranée, n°. 69, 2004; Yvan Gastaut, « L’Italien anarchiste à Nice dans les rapports de police à la fin du xixe siècle : la figure introuvable du terroriste », Recherches régionales, Centre de documentation des Alpes-Maritimes, 48e année, 2007, n°187, pp. 9-16.

Pierre Birnbaum, Les fous de la République, Fayard, 1992.

Édouard Drumont, La France juive. Essai d’histoire contemporaine, Flammarion, 1886.

The last recorded anti-Jewish attack in France occurred in Durmenach (Bas-Rhin) in February 1848. There was material damage but no casualties. The village priest gave asylum to Jews who were unable to flee.

Pierre Birnbaum, Le moment antisémite. Un tour de la France en 1898, Fayard, 2015 [1998].

Léon Blum was the victim of an attempted mugging on 13 February 1936. It should be pointed out that violence against political leaders was common at the time, including against the Action française, since several of its leaders had been murdered by anarchists (Marius Plateau in 1923, Ernest Berger in 1925). See Emmanuel Debono, « Les années 1930 en France : le temps d’une radicalisation antisémite », Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah, vol. 198, n°1, 2013, pp. 99-116 [online].

Emmanuel Debono, « Radiographie d’un pic d’antisémitisme. La crise de Munich (automne 1938) », Archives Juives, vol. 43, n°1, 2010, pp.77-95 [online].

This analysis has been supported by a number of historians: Alain Michel, « Vichy désirait protéger tous les Français, dont les juifs », Causeur, 25 November 2021; Jean-Marc Berlière, « La rafle du vel’ d’hiv’ vue par les médias et les politiques : c’est l’histoire qu’on assassine ! », Causeur, 9 August 2022.

Jacques Semelin, Une énigme française. Pourquoi les trois quarts des Juifs en France n’ont pas été déportés, Albin Michel, 2022; Pascale Tournier, « Jacques Semelin : “Concernant le maréchal Pétain et les juifs français, Zemmour a exploité une faiblesse de l’historiographie” », La Vie, 4 January 2022 [online]. See also Annette Wieviorka, « Vichy n’a pas sauvé les Juifs », L’Histoire, 6 January 2022 [online].

Laurent Joly, L’État contre les juifs. Vichy, les nazis et la persécution antisémite, Grasset, 2018.

In general, racism is assessed only on the basis of opinions and prejudices. However, acts of racism belong to an entirely different register. While prejudices may be widespread, acting upon them follows a different logic, as the psychologist Richard LaPiere observed along his journey with a Chinese couple in 1930s America.16

In France, acts of racist violence are rare. Outbursts of violence have occured on certain occasions, such as during the Aigues-Mortes riots in 1893, when a dozen Italian workers were lynched by the crowd. This type of event was an exception, however, and needs to be put into in context. In Aigues-Mortes, not only was fierce competition for jobs exacerbating tensions, but terrorist attacks were being committed by anarchists – many of whom were Italian – such as the infamous Caserio, who assassinated President Sadi Carnot.17

Even in 1930s France, at the height of an unprecedented wave of immigration and with far-right leagues in full swing, there were no recorded massacres or killings of foreigners, at a time when political violence was widespread across Europe.

The same is true for the Jews: no pogrom has taken place in France since the one in Strasbourg in 1349. While antisemitism re-emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, it did so in the context of intense conflict between Republicans and Catholics. The Republicans had launched a vast purge of the State, brutally removing Catholics from the administration, the army and the judiciary. They were accused of giving free rein to Freemasons, Protestants and Jews. For their part, many Jews supported the Republic18, which exacerbated resentment against them.19

But antisemitism remained essentially verbal. During the Dreyfus Affair, often described as a the peak of antisemitism, no Jewish person was killed or even attacked.20

Pierre Birnbaum spoke of a “victimless pogrom”.21 The expression is not very apt, but underlines that calls to violence remained merely a “virtual threat” (Birnbaum), incomparable with the massacres carried out in Russia, Ukraine, Vienna, Warsaw, Constantine, or Hebron.

Although historians have noted “alarming signs” in the 1930s, acts of violence – albeit poorly documented – were very few.22 The peak seems to have occurred in 1938 during the Sudeten crisis. Faced with the threat of war, Jews were accused of inciting confrontation. There was a spike in threats, insults, graffiti, broken glass and some assaults, particularly in Alsace and Lorraine.23

The fascist threat was then brandished by the left. Leagues thrived, particularly among veterans, but the far right had no electoral presence, unlike in Italy and Germany at the time. The main league, the Croix-de-Feu, was republican and strongly anti-fascist. The germanophobia of its leader, Colonel de La Rocque, who denied any antisemitism, led him early on to join the Résistance (a term which he coined) before being arrested and deported by the Germans.

Even under the Vichy regime, there were hardly any attacks or murders of Jews committed by individuals. It is worth noting that, to counter certain claims that Marshal Pétain saved French Jews, several historians have argued that if the vast majority of French Jews survived during the war, it was largely due to the help of ordinary French people – including police officers during the Vel d’Hiv round-up.24 Jacques Semelin speaks of “the solidarity of small gestures”25 and the historian Laurent Joly points out that, contrary to legend, few Jews were denounced.26

This optimistic assessment should not, of course, lead us to forget the racist attacks and crimes that have punctuated contemporary history, particularly the ratonnades of the 1960s and 1970s, as in Marseille in 1973.27 But once again, these violent acts needs to be put into perspective and contextualised. They took place in the wake of the Algerian war, during which each side was highly radicalised while retaining a deep aversion to the other. The events of May 1968 increased ideological polarisation. Far-left and far-right groups clashed violently and attacked those they saw as allies of the opposite camp.

The oil crisis exacerbated tensions linked to immigration from the Maghreb. Unemployment, which had already been on the rise since the late 1960s, entered a new phase and the government halted labour immigration in 1973. It was against this backdrop that violence against North Africans broke out in Marseille, following the murder of a bus driver by an Algerian man. The violence was often led or encouraged by former members of the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (OAS) and the army.

While these tragedies are far from negligible, they should not be overemphasised in the interpretation of the situation: at the same time, France was welcoming large numbers of Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees (the boat people) fleeing Communist regimes, which only serves to highlight the specific nature of the Franco-Algerian dispute.

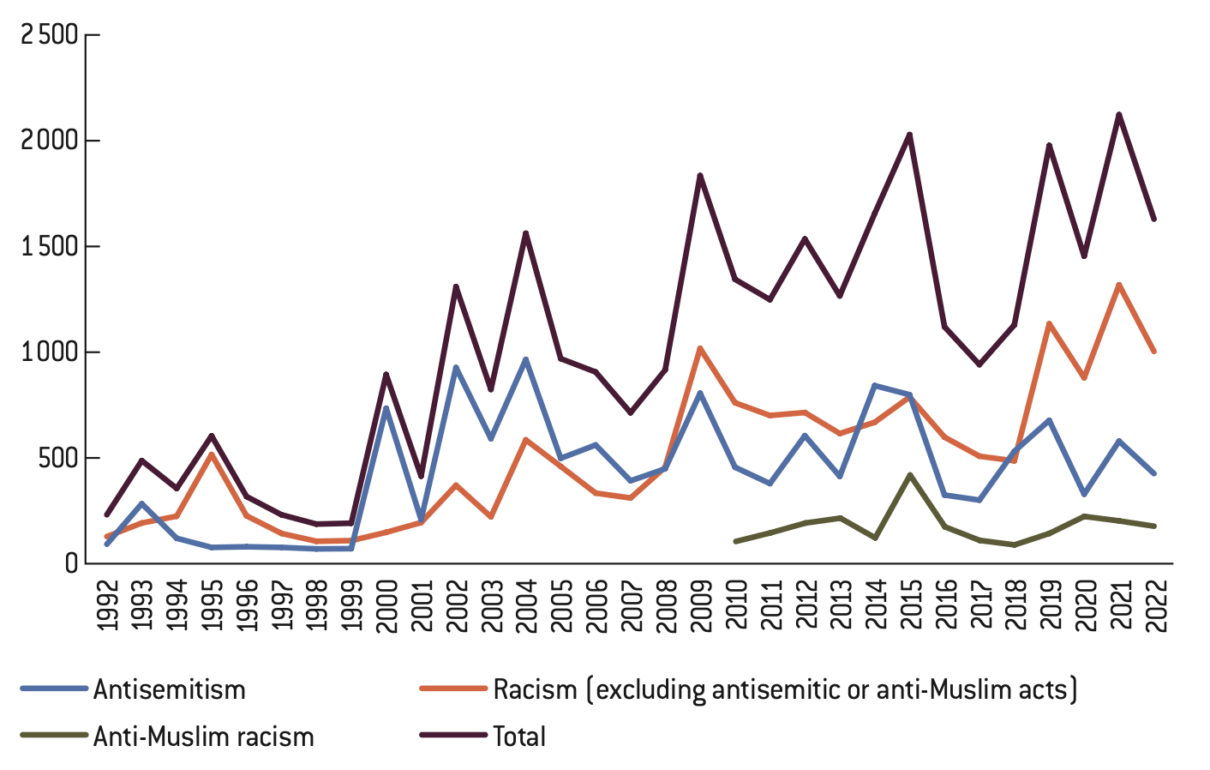

Figure 3: Trends in racist incidents recorded by the SRCT (1992-2022)

Source :

CNCDH annual reports

Allan Kaval, « Agressions contre des Roms : “Depuis l’attaque, on hésite à sortir, à aller faire nos courses, à aller travailler” », Le Monde, 19 March 2019 [online].

Jean Chichizola, « À Dijon, l’incroyable expédition punitive de Tchétchènes », Le Figaro, 15 June 2020 [online].

In 2019, 15 new offences have been added.

Anti-Christian acts have only been counted since 2018 and are counted separately. They are around twenty times higher than anti-Muslim acts (760 compared to 42 in 2019, 492 compared to 22 in 2020).

Although a precise analysis has yet to be carried out, an inventory of racist incidents since 1992 shows that there has been a deterioration since 2000 (Figure 3). This deterioration is primarily based on the increase in antisemitic acts, the origins of which seems to lie with the Muslim population, who project the Israeli-Palestinian conflict onto the Jews, as occured after the massacres committed by Hamas on 7th October 2023.

The rise in racist acts recorded since 2019 is worrying, but the lack of information on perpetrators and victims makes interpretation difficult. France’s ethno-religious diversification may have increased conflict situations, as evidenced by the emergence of inter-community rivalries. In early 2019, for example, there was a punitive expedition in quartiers sensibles (neighbourhoods characterised by social and economic challenges) in the Paris region against Roma, accused of kidnapping children28, or a Chechen expedition against Algerians in Dijon in June 2020.29 Moreover, the legislation evolved in 2018: seven new offences can now be incriminated for racism. This includes, in particular, insulting a public official, an offence that has seen a significant rise (from 27 in 2018 to 192 in 2019).30

Anti-Muslim acts are few and far between, especially when compared with anti-Christian acts.31 The Islamist terror attacks of 2015 caused a slight spike in acts against Muslims, but France did not experience the equivalent of the murders committed in Canada (6 deaths on 29 January 2017) or New Zealand (51 deaths on 15 March 2019). This confirms that the anti-Maghrebi violence of the 1970s was indeed linked to a specific context.

Proof from Aya Cissoko?

One question is rarely considered by proponents of structural racism: what do the victims have to say about it? What does this supposedly omnipresent racism actually mean? The testimony of former French boxer Aya Cissoko, who left the rings to become a writer, is worth listening to attentively, as she was emphatic: “There is real structural racism in France”, adding: “I have been confronted with racism all my life”.

When the journalist asked her to explain how this racism manifested itself, she gave the following answer:

“In a very insidious way. Racism doesn’t necessarily mean someone shouting ‘dirty Black’ or ‘dirty nigger’ at you in the street. These are ‘microaggressions’. Racism is, for example: you’re pregnant, you’re in the lab waiting for some test results, you’re reading a book by Stefan Zweig and someone right next to you says, ‘oh you read that?’ Another example of racism is the fact that you’re a champion and the press is always going to write ‘champion of Malian origin’. What is supposed to sound like an addition, feels like a subtraction. In other words, I’m not entirely French, not fully French, I’m ‘French but…’. And therein lies the problem”.32

Such an account leaves one wondering. Far from supporting the thesis of structural racism, it highlights its limitations. Can we speak of structural racism when it manifests itself in the form of “micro-aggressions” or “feelings”, without it being possible to detect more measurable manifestations? How is being surprised to see someone reading Stefan Zweig at the doctor’s surgery a racist attack? Is it not more simply an attempt – no doubt clumsy – to make contact? Similarly, why is it insulting to point out someone’s origins, especially at a time when migration is often brandished as a badge of pride?

Aya Cissoko’s story is all the more unsettling because her own life story suggests a diametrically opposite reading. At the start of her interview, she recalls the tragedy she experienced as a child, when her father and sister died in an arson attack, apparently claimed by the far right. It was a terrible tragedy, but she was subsequently supported by public and private institutions. Her family was quickly rehoused. She herself went to school and was able to find associations that gave her the opportunity to practise the sport of her choice, enabling her to cultivate her talent. After an injury, she was admitted to Sciences Po thanks to sponsorship from the Lagardère foundation. She then took up writing and found publishers to support her, first Calmann-Lévy, then Le Seuil. Her first novel won an award from Le Figaro before being adapted into a screen production.

Admittedly, Aya Cissoko has not had an easy life. She has encountered difficulties and even tragedies, and she has had to face them head on. But there is nothing to suggest that French society has failed her.

Let’s go a step further. Aya Cissoko sees the origins of French racism in “a history of slavery and colonisation” – the two being confused. She recalls that it was because of this colonisation that her parents came to France, because “France needed people to build its roads and fill its factories”.33

Curiously, her critical assessment of the past does not go so far as to point out that her parents come from a country, Mali, which was itself a slave state before the arrival of the French and that, without colonisation and her family’s migration to France, she might not have been able to enjoy the same opportunities in life.

Structural anti-racism

The geopolitical and cultural pre-eminence of the United States since 1945 has ultimately created an optical illusion: believing that what happens over there also happens in France. Has a French Interior Minister not considered kneeling, following the Black Lives Matter movement and the George Floyd case?34 During the Euro 2020, which took place in 2021, the entire French team announced that they would participate in this new ritual, only to back out at the last minute in the face of protests.35

This Americanisation of the national imagination should not, however, be misleading. French society is very different from American society, particularly on the issue of race and racism. A basic reminder of some of the characteristics of American history helps to better understand this difference.

Race in the United States

Olivier Richomme, « Race et citoyenneté aux États-Unis : restrictions raciales à la naturalisation aux XIXe et XXe siècle », Miranda, n°7, 2012 [online].

Daniel Sabbagh, « Le statut des “Asiatiques” aux États-Unis. L’identité américaine dans un miroir », Critique internationale, vol.20, n°3, 2003, pp.69-92 [online].

Griggs v. Duke Power Company (1971) held that neutral tests could be discriminatory, and while the

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) prohibited racial quotas in universities, it accepted that

compensation mechanisms could be introduced. Several subsequent rulings have ruled that racial quotas in

private or public companies are legal.

See Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard College, 29 June 2023.

James Whitman, Hitler’s American Model. How American racial laws inspired the Nazis, Armand Colin, 2018.

Pap Ndiaye, « États-Unis : un siècle de ségrégation », L’Histoire, n°. 306, February 2006.

Guillaume Mouralis, « Race et droit aux États-Unis : l’ombre de Nuremberg », La Revue des droits de l’homme, n°19, 2021 [online].

The Census Bureau distinguishes five races: White, Black or African American, American native or Alaska native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, see “About the Topic of Race”, U.S. Census Bureau, 20 December 2024 [online].

“Frequently Asked Questions: EEO-1 Component 1 Data Collection”, U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

“As a general principle, an Indian is a person who is of some degree Indian blood and is recognized as an Indian by a Tribe and/or the United States”, see “Frequently Asked Question about Native Americans”, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Tribal Justice [online].

One site calculates the percentage of Indian blood possessed and ranks tribes according to the percentage needed to be considered a member. See “What Percentage of Native American Do You Have To Be To Enroll With a Tribe?”, PowWows.com, 5 January 2024 [online].

A case of racial discrimination dating back to 1966, before the 1972 law, was punished by the Seine criminal court for refusal to sell and public insult. See Emmanuel Debono. Le racisme dans le prétoire. Antisemitism, racism and xenophobia before the law, PUF, 2019.

It is no coincidence that terms such as “structural racism” or “institutional racism” have flourished in the United States. In this country, racism has been at the heart of the social contract through the issue of slavery. The 1787 Constitution, which followed the failure of the Confederation, was only agreed upon between the states in exchange for a guarantee not to interfere with slavery (the Connecticut Compromise) and to adjusting the weight of each State based on the number of slaves.

This institutional arrangement gave rise to recurrent debates on the balance between slave-holding and non-slave-holding states. Above all, it has led to race becoming a societal and legal norm. Case law has gone so far as to deprive Black people of their citizenship (Scott v. Sandford, 1857) and legislation has long referred to “White persons” in determining eligibility for naturalisation,36 forcing the Supreme Court to engage in legal contortions to determine who qualified as such.37

A glaring contradiction was thus established between the egalitarian ideal and legal reality. This contradiction could only be resolved through a particularly bloody civil war, but the issue did not end in 1865.

Laws enforcing racial segregation were upheld by the Supreme Court in its 1896 decision (Plessy v. Fergusson). In the Southern states, where the Democratic Party had long been dominant, an alternative national memory emerged – one that idealised the pre-Civil War period and encouraged a lenient view of racism and the practice of slavery.

The issue of race remained a deeply structuring force for a long time. In 1919, President Wilson opposed the Japanese proposal to include “racial equality” in the statutes of the League of Nations. This proposal stipulated that the signatory states would not make distinctions on the basis of race. The American veto was experienced as a humiliation by Japan, which was particularly sensitive to the treatment of its nationals in the United States. In California, for example, Japanese were denied access to public education and a 1913 law prohibited them from acquiring land.

The issue of race has therefore had a profound impact on American society. This explains why the affirmative action policies of the 1960s and 1970s were able to use race as a reference point, with the more or less explicit support of the Supreme Court, whose rulings at times ran counter to the constitutional principle of equal protection under the law.38 It is not without a certain irony that the Supreme Court, in its recent ruling against of affirmative action in universities, noted that Harvard University had notoriously distinguished itself in the interwar period by imposing quotas on Jewish students.39 The racial and segregationist policies implemented in the United States were so harsh that they attracted interest from Nazi Germany.40

The war against Nazi Germany undermined the doctrinal foundations of racial segregation in the United States.41 Nevertheless, American jurists had to exercise caution during the Nuremberg trials to avoid establishing a legal precedent that could have backfired on their own country.42

This racialist legacy has left its mark. Public statistics in the United States make extensive use of ethnic and racial criteria, even though, since the year 2000, censuses have relied on racial self-identification:

individuals are free to indicate the race to which they belong; they even have the option to indicate several.43

Race continues to be used in public policy. Under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, companies with more than 100 employees (or fewer if they belong to a group or receive public contracts) are required to submit a confidential report entitled EEO-1 (Equal Employment Opportunity) to assess their efforts in terms of ethnic and racial diversity. The EEO Commission encourages employers to rely on the racial self-identification of their employees; if employees refuse, it is up to the employer to declare the race of its employees, as all must be identified.44

The issue of Native American tribes also contributes to legal racialism, as membership in a tribe has very significant legal implications (local government participation, access to land ownership and tribal jurisdiction, etc.). A genealogical classification must therefore be established. An Indian is defined as “a person who has a certain degree of Indian blood”45; it is the responsibility of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to issue a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB).46

In 1972, anti-racist legislation was adopted (the Pleven law). Its legal usefulness is debatable, but at the time it was intended to facilitate the movement of overseas populations to metropolitan France, some of whom had expressed their desire to remain French.47

Even in the case of Gypsies, who have always sparked strong aversion in public opinion, legislation has refrained from invoking race. The law of 1912, adopted in a very hostile climate, relied solely on a strictly social criterion: a nomad is someone who does not have a fixed residence.48 It even took care to distinguish between nomads and travelling workers, considering that the latter, by virtue of their activity as itinerant traders, fell into the category of seasonal workers. The term « gens du voyage » (“travellers”), which has appeared in administrative vocabulary since the 1970s, is an even more blatant rejection of biological criteria, whereas the Gypsies have fewer qualms about asserting their ethno-racial identity.

Despite what may be said, for all the reasons mentioned above, French society has developed a deep-seated reticence towards origins, even when certain issues are at stake. This is why positive discrimination in France, implemented in the context of priority education (1981) or urban policy (1990), has relied solely on social and geographical criteria, and never on racial or ethnic criteria.

The Invisibility of Origins

Patrick Ténoudji, « Les minorités invisibles. Être “noir” dans une entreprise d’insertion en banlieue parisienne : parcours d’intégration », Les Temps Modernes, vol. 615-616, n°4-5, 2001, pp. 180-205 [online]; Vincent Geisser, « Minorités visibles versus majorité invisible : promotion de la diversité ou de la diversion ? », Migrations Société, vol. 111-112, n°. 3-4, 2007, pp. 5-15 [online].

A law passed in 2004 prohibits the collection of data that “directly or indirectly reveals racial or ethnic origins”, and the French Constitutional Council has prohibited studies that take into account “ethnic origin or race” on the grounds that such information does not form part of “objective data” (decision of 15 November 2007).

Michèle Tribalat, « Une innovation dans le bulletin de recensement qui pourrait en cacher une autre : l’abandon de la définition actuelle des immigrés », micheletribalat.fr, 2 May 2022 [online].

Jean-Marc Leclerc, « Polémique sur le fichage selon la couleur de peau », Le Figaro, 5 December 2008 [online].

Isabelle Rey-Lefebvre, « Le bailleur social Logirep condamné en appel pour ‘discrimination raciale’ »,

Le Monde, 18 March 2016 [online].

Hervé Le Bras, Le démon des origines, Éditions de l’Aube, 1998.

« Inactivité, chômage et emploi des immigrés et des descendants d’immigrés par origine géographique. Données annuelles 2023 », Insee, 29 August 2024 [online].

In February 2015, at a CRIF dinner, François Hollande was not afraid to accuse “ French of native descent” of desecrating a Jewish cemetery. See Alexandre Devecchio, , « “Français de souche, comme on dit” : le décryptage de Michèle Tribalat », Le Figaro, 24 February 2015 [online].

An accusation has emerged in recent years that the Republic is rendering ethnic minorities “invisible”, an accusation that has been reinforced by the 2004 and 2010 laws on religious symbols and the burqa.49

While this accusation illustrates the rise of the multiculturalist framework to the detriment of the assimilationist framework, it implicitly confirms that the French political and legal tradition has always refused to take physical criteria into account. To say that the Republic makes minorities invisible is to acknowledge that it is blind to origins: individuals must be judged on the basis of their qualities and personality, not their appearance or genealogy.

This is why race has never featured in national censuses, unlike in the United States or in England. Statistics on origins continue to be tightly regulated.50 Public institutions responsible for collecting statistics refuse to allow any indicators that could resemble the identification of origins. Even a question on the nationality of parents at birth has become suspect, as it is deemed potentially stigmatising, and has thus been removed from the 2025 census, which may make it more difficult to count immigrants.51

In criminal matters, where it is rather necessary to identify individuals on the basis of their appearance, race is also rejected in principle. The National DNA Database (Fnaeg, established in 1998) only archives non-coding DNA, i.e. segments that do not reveal any information about a person’s physical characteristics, with the exception of gender. The inclusion of ethno-racial information in the police’s offence database (The Système de traitement des infractions constatées – STIC) has been very poorly accepted, notably by the independent French administrative authority that ensures the protection of personal data and privacy (the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés – CNIL) and the Human Rights Defence Authority (the Défenseur des Droits), but indifference to race has reached its limits here, as it seems difficult to conduct investigations without this information.52

All claims based on race (for example, so-called “ethnic” statistics or racial quotas in companies and administrations) have come up against a brick wall. This situation does not exclude perverse effects, such as when a social landlord was convicted for trying to avoid the overrepresentation of an ethnic group in one of its buildings, but it does confirm that French society is fundamentally averse to race.53

This aversion to origins is reflected in the great caution exercised by the media and social sciences. Acts of incivility and crime are never documented according to the ethnic characteristics of their perpetrators. The same applies to harassment in the street or in schools, or to domestic and marital violence. Only nationality is ever taken into account, for example in prison administration statistics.

Another sign of this aversion is the profound disgrace that has befallen the expression Français de souche (French of native descent).54 This discrediting is consistent with the anti-racialist rationale: in a society where genealogical origins are becoming more diverse, emphasizing one’s Franco-French ancestry is a way of distinguishing oneself that may seem incompatible with civic equality. However, this disgrace has created a void: how should we refer to the French who are not of immigrant origin? The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) refers to them as “people with no migratory ancestry”,55 while the National Institute of Demographic Studies (INED) refers to them as “non-immigrants”.56

A pattern is emerging behind these subtleties: the historic people tend to be defined negatively on the basis of a lack. They cease to be the reference norm, which shifts towards populations who have come from elsewhere: since there are no such French of native descent, every French person is an immigrant, unbeknownst to them.

A shift then threatens to occur. Not only is the native Frenchman no longer mentioned – except, perhaps, when he is to be criticised – but the notion that France owes its very foundations to foreigners is gaining traction.57 “Our great-grandparents liberated France, our grandparents rebuilt it, our parents cleaned it up. We’re going to tell the story”, comedian Jamel Debbouze summarized in 2006 during the release of the film Indigènes, which won an award at the Cannes Film Festival.

Public institutions sometimes embrace this shift, as Pap Ndiaye did when he was director of the Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration (National Museum of the History of Immigration): “Our mission is to make immigration a central part of national history”.58 Upon its reopening in the spring of 2023, after three years of renovation work, it launched an advertising campaign featuring a portrait of Louis XIV accompanied by the slogan: “It’s amazing how many foreigners made French history”. This presentation was surprising in more than one respect: not only did it celebrate a king who enacted the Code Noir and revoked the Edict of Nantes, but it also implied that a child of a foreigner – since Louis XIV’s mother was Spanish – remains a foreigner forever.

The Visibility of the Invisible

Paul Yonnet, Voyage au centre du malaise français. L’antiracisme et le roman national, Gallimard, 1993.

« Minorités invisibles », Le Monde, 21 July 2000. Calixthe Beyala went on to publish several similar articles. See Florence Hartmann, « Calixthe Beyala, “Il n’y a pas de Navarro ou de Julie Lescaut noirs” », Le Monde, 10 October 1999 [online] ; Calixthe Beyala, « Les Africains-Français attendent », Le Monde, 11 March 2002 [online].

Au nom de tous les miens (In the Name of All My Own) is the title of the autobiography by Martin Gray, a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto and Treblinka

« En février 2000, Luc Saint-Éloy bousculait “la grande famille du cinéma”. Depuis, rien n’a changé… », 97LAND, 9 March 2020 [online].

See the report « La représentation de la société française dans les médias audiovisuels », Arcom, July 2022 [online].

For a more detailed analysis, see our contribution to Emmanuelle Hénin, Xavier-Laurent Salvador and Pierre Vermeren, Face à l’obscurantisme woke, PUF, 2025 (forthcoming).

Renaud Dely, « Le Pen fait sa sélection des footballeurs pas assez français », Libération, 26 June 1996 [online].

Isabelle Rüf, « France Culture accuse l’écrivain Renaud Camus d’antisémitisme », Le Temps, 25 April 2000 [online].

Pap Ndiaye and Constance Rivière, Rapport sur la diversité à l’Opéra national de Paris, January 2021 [online].

Thomas Sotinel, « Omar Sy et le docteur Knock, un rendez-vous raté », Le Monde, 18 October 2017 [online].

The media did speak of a “controversy” over the pageant, but without pronouncing any radical condemnation. See « Mbathio Beye, première “Miss Black” française », France Info/AFP¸ 29 April 2012 [online]; « Mbathio Beye est la première Miss Black France », Elle, April 2012 [online]; Anna Benjamin, « Miss Black France, un concours de “beautés noires” qui fait polémique », Le Monde, 27 April 2012 [online].

Sylvie Laurent, « Le “petit Blanc” n’est plus ce qu’il était », Le Monde, 2 October 2012 [online]

France O, 26 March 2015.

Donia Ismail, « Stormzy, le rappeur qui met sa célébrité au service des communautés noires », Slate, 30 May 2023 [online]. The article ends with praise for Stormzy’s “incisive words”: “If you try to rob them for their dreams, of course I’m gonna put a target on your back”. A White singer saying the same thing would probably not provoke the same indulgence.

As Paul Yonnet aptly pointed out, the anti-racism movement of the 1980s paradoxically brought the issue of racial identities back into the public debate.59 Identity-based demands became increasingly important, albeit often masked by euphemistic language (« Beurs », « Maghrébins », « Blacks », « Renois », « Rebeus »).

The year 1998 accelerated this change of direction. The victory of France’s Blanc Black Beur team was accompanied by the birth of the Égalité collective, created by several artists of African origin: Calixthe Beyala (novelist), Manu Dibango (musician), Luc Saint-Éloi (director) and Dieudonné (actor). This collective condemns the treatment of Black people and their underrepresentation in society. The association’s president, Calixthe Beyala, criticises the education system for ignoring Black slavery. She demands racial quotas in employment and the media.60 During the 25th César Awards ceremony, along with Luc Saint-Éloy, she proclaimed herself the spokesperson for a community defined by race, denouncing the absence of visible minorities. In passing, she made an explicit comparison with the situation of Jews, via the writer Martin Gray:

“In the name of 8 or 20 million of these citizens [from visible minorities], in the name of all my people,61 and this is not a film title, in the name of the just and legitimate fight that the Égalité collective is waging for a true representation of the multiracial reality of France in all the media and in all places of culture, we wish to tell you that the situation we have been subjected to for too long flouts any notion of human dignity”.62

After holding hearings with the Égalité collective, the Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (the French Broadcasting Authority – then CSA, now ARCOM) began counting screen appearances according to skin colour. Its annual reports deplore the fact that “people perceived as non-White” represent only 14% of the characters shown on television screens. But how do we know who is perceived as White or non-White? And above all, how can we know, in the absence of national statistics on race, whether the proportion of “non-Whites” established by the CSA is not overrepresented relative to the actual demographic composition of the country?63 Such a count remains rather peculiar and rather incompatible with an institution of the French Republic.64

A break has certainly occured. It is even considerable when recalling the virulent reactions that accompanied Jean-Marie Le Pen’s remarks on the proportion of players of foreign origin in the French national football team,65 or those of the writer Renaud Camus on the number of Jews in France Culture programmes.66

Once strongly condemned, this type of categorization is now gaining legitimacy. The president of France Télévision, Delphine Ernotte, has not hesitated to declare her intention to put an end to “a television of White men over 50” (23 September 2015). Similarly, an official report sets out to catelogue the staff of the Paris Opera based on racial criteria.67

There is a back-and-forth at work: while the majority is called upon to be discreet, or even to make amends for its past faults, minorities are invited to proudly display their origins.

The invisible must become visible. In films, Black actors play White characters, such as Omar Sy who plays Doctor Knock in the 2017 film Knock, while the paperback edition of Dom Juan features a Black actor on its cover.68

This situation would hardly be imaginable in reverse: it is hard to picture a White actor playing a Black personality without being accused of blackface. A « Miss Black France » competition was held in 2012 without facing significant opposition, whereas it would be entirely unthinkable to have a ‘White only’ Miss France competition – a competition that has crowned several women of colour over the years, from Sonia Rolland, of Rwandan origin (2000), to Angélique Angarni-Filopon from Martinique (2025).69

The Conseil représentatif des associations noires (the Representative Council of Black Associations, CRAN, created in 2005) has no equivalent among White people, and while the press may speak condescendingly of “little White people”, it is hard to imagine them using the same tone when talking about “little Black people”.70 Could the Folies Bergères musical Black Legend, which aims to trace “four centuries of Black people” based on the great African-American singers, be transposed into “White Legends”?71 If a news site can praise an American rapper “who puts his celebrity at the service of Black communities”, it seems hard to imagine the same enthusiasm for a singer who would serve “White communities”.72

The Myth Of Structural Racism

Vincent Tournier, « Misère de l’intersectionnalité », Commentaire, n°189, Spring 2025.

Like other contemporary ideologies (for example, decolonialism, gender theory or intersectionality),73 with which it shares connections, the thesis of structural racism is based on elements that are, at best, questionable and superficial, and at worst, false and misleading.

The question then becomes why such a thesis has emerged and gained ground in France, even within academic circles, when it exhibits all the characteristics of a scholarly conspiracy theory or, at the very least, false pseudoscience. Answering this question requires taking a detour through the analysis of myths.

On the Origin of Myths

Claude Lévi-Strauss et Bernard Pivot, « Claude Levi Strauss définit les mythes », INA, 4 May 1984 [online].

Didier Anzieu, Le travail de l’Inconscient, Didier Anzieu, 2009, chapter 2.

Jean-Pierre Vernant, «Œdipe sans complexe », in Raison présente n°. 4, August-September-October 1967 [online].

Girardet Raoul, Mythes et mythologies politiques, Seuil, 1990.

According to Claude Lévi-Strauss, a myth is a narrative whose function is to describe the origin, the present and the future of things.74 It is related to ideology but differs in that it has no explicit political project.

Freud proposed that myths could be explained by internal conflicts linked to anxieties and psychological impulses. He concluded that “mythology is a projected psychology”.75

While myths certainly borrow aspects from psychology, they also reflect the “social thought” of a society by expressing “the tensions and contradictions that arise within it”.76 This is why myths tend to emerge in times of crisis or difficulty.77 When traditional narratives become obsolete, new ones emerge to help resolve tensions and give meaning to the new order of things.

Myths have an ambiguous relationship with reality: they both draw inspiration and distance themselves from it. In his novel Përbindëshi (The Monster), published in 1965, the Albanian writer Ismaël Kadaré put forward the hypothesis that the myth of the Trojan horse served to conceal a less glorious story, namely that the Greeks had succeeded in defeating their adversaries by signing a peace agreement that they did not honour. A horse was no doubt among the gifts exchanged. It was on this basis that the myth could take shape, its function being to erase the shame associated with this act of treachery.

Following this line of thought, the myth of structural racism could be seen as a response to the contradictions of the present age and as a way to avoid facing an unsettling reality. The postcolonial period raises difficult questions: why was the end of the colonial empire accompanied by significant immigration from the former colonies, and why do immigrants and their descendants sometimes struggle to integrate?

This facilitates the creation of a sense of coherence. Not only does it give meaning to France’s failure in its former colonies, it also serves to deflect accusations of racism that could be directed at the decolonial movement itself – since that movement justified decolonisation by the need to preserve the identity of the indigenous peoples, defined precisely by criteria that would never have been accepted if applied to the French: blood, ancestry and land. In this way, the decolonial movement rehabilitates the idea of a racial struggle as a key to understanding history – an idea reminiscent of the theory of the Germanic origins of the nobility or the racial conflict central to Augustin Thierry’s work.

The myth of structural racism is also a way of resolving a conflict between, on the one hand, the idealisation of immigration – an idealisation that views formerly colonised populations as victims in need of protection – and, on the other, a migratory reality that turns out to be far less positive than expected, especially given that the countries of origin have not become the peaceful and democratic havens hoped for by decolonisation advocates.

The myth thus allows all these difficulties to be pushed aside. It serves to resolve a kind of “psychological suffering” in the Freudian sense, by offering a comforting explanation that shifts the responsibility for integration problems onto the host society.

Instrumentalization

Paul Veyne, Les Grecs ont-ils cru à leurs mythes, 1983.

The Musulmans en France information website readily denounces “State racism” : « Mort de Nahel, le racisme d’État en question », Musulmans en France, 30 June 2023 [online].

« Il est urgent de s’attaquer au racisme systémique et aux doctrines de supériorité raciale », United Nations, 14 November 2022 [online] ; « Racisme : taux disproportionnés de décès de personnes d’ascendance africaine par les forces de l’ordre dans différents pays », United Nations, 30 September 2022 [online]; “Tackling structural racism and ethnicity-based discrimination in health”, World Health Organization [online].

The American press is often very critical of France’s treatment of minorities, which may be explained by the desire to reject the Republican model and relativise racial problems in the United States. See for example this article published after the murder of Samuel Paty: “Instead of fighting systemic racism, France wants to ‘reform Islam’”, Washington Post, 23 October 2020 [online].

For example, Turkish President Erdogan regularly accuses France: “Today, cultural racism has turned into institutional racism in many European countries, especially in France”. See Ayvaz Çolakoğlu, « Erdogan : en France, on est face à un racisme institutionnel », Anadolu Ajansı, March 2021 [online]. The urban riots of June 2023 gave him the opportunity to take up this accusation of “institutional racism”. See « “Passé colonial”, “racisme institutionnel”: Erdogan donne sa version des émeutes en France », BFMTV, 3 July 2023 [online].

Pierre Martin, « Le Vote Le Pen : l’électorat du Front national », Note de la Fondation Saint-Simon, n° 84, 1996 ; Jérôme Fourquet, « 1983 : année charnière pour le Front national », Fondation Jean-Jaurès, 7 March 2018 [online]

Laurent Bouvet, L’insécurité culturelle, Fayard, 7 January 2015.

« En Algérie, Macron qualifie la colonisation de “crime contre l’humanité”, tollé à droite », Le Monde, 15 February 2017.

According to a Harris Interactive poll of 2,544 people conducted for Challenges in October 2021, 61% of those questioned believe that the ‘great replacement’ is going to happen, and 67% say they are worried about it. The theme was presented as follows: “Some people are talking about the ‘great replacement’: White, Christian European populations being threatened with extinction as a result of Muslim immigration from North Africa and Black Africa”. Baromètre d’intentions de vote à l’élection présidentielle de 2022 – Vague 18, Harris Interactive for Challenges, 20 October 2021 [online].

A myth does not necessarily have to be believed.78 Legendary narratives provide a psychological comfort that short-circuits any questioning. Although myths are not always taken seriously, they nonetheless fulfill social function and serve certain interests.

Anti-racist activists need to dramatise the situation in order to better justify their cause and sustain the commitment of their members.79 The many associations whose mission is to combat racism or assist migrants – now fully-fledged actors in migration policy – have a vested interest in maintaining a pessimistic view of French society in order to justify their role and secure funding.

The same applies to independent administrative agencies and international organisations, part of whose activity involves exercising a form of moral authority, which encourages them to adopt a highly critical discourse on French society.80

The moral condemnation of racism can also be amplified by foreign media81 or by countries with an interest in criticising France.82 Intellectuals and academics have every incentive to endorse the thesis of structural racism in order to ride the wave of post-materialistic values that have emerged from decolonisation and the post-war economic boom (the Trente Glorieuses): By presenting themselves as crusaders against a looming racism, they position themselves up as guardians of virtue – earning media and academic recognition at little cost.

More broadly, the myth of structural racism has the advantage of offering a convenient interpretation of the political situation. By focusing on the racism of the French population, it avoids questioning the mechanisms that have allowed the Front National (FN – a far-right populist part in France) to prosper, even though its success does not in any way signify the end of the anti-racist norm: in fact, it is precisely because the FN has been perceived as a racist party that its electoral growth has been contained, despite strong public concern about immigration and security.

The myth of structural racism prevents us from seeing the support for the FN (now Rassemblement National – RN) vote stems less from deep-rooted French racism than from a sense that successive governments have been overly accommodating towards foreigners.83 Part of public opinion may have felt that a fundamental element of the social contract had been broken. A political insecurity has been added to the cultural insecurity highlighted by Laurent Bouvet: are the elites still committed to defending the people, given that their focus is now firmly set on Europe and globalisation, all the while managing to shield themselves from the negative effects of a process from which they largely benefit?84

Moreover, the crisis of trust is fuelled by the perception that two narratives are clashing: a positive discourse about foreigners, and a disparaging one about the French themselves. From Jacques Chirac evoking France’s “responsibility” in the deportation of the Jews, to Emmanuel Macron describing colonisation as a “crime against humanity”, and the Taubira law focusing solely on the condemnation of the Western slave trade, French voters may feel that they are being blamed collectively by their own leaders.85

The popularity of the expression « Grand Remplacement » (the “Great Replacement” theory) likely stems less from actual demographic changes – although these are hardly disputable – than from the feeling that the elites have their role of protecting and valuing their own population.86 While the phrase « nos ancêtres les Gaulois » (“our ancestors the Gauls”) is now considered a racist expression, a consortium of public institutions (INRAP, France Télévision, CNC, Institut du monde arabe) produced a documentary entitled Nos ancêtres, les Sarrasins (Our Ancestors, the Saracens), which was promoted up by Le Monde without provoking any real debate.87

Over-Interpretation

“Universalism is portrayed as a tool of structural racism. It has indirectly allowed for the perpetuation of racial categories and the inherent violence associated with them”, writes Rachida Brahim. See Rachida Brahim, « La législation antiraciste française, support d’un racisme structurel », in Race et racismes, Communications, vol. 107, 2020 [online].

Abdellali Hajjat, « Race et droit de la nationalité en contexte postcolonial : le cas de refus de naturalisation au motif de la polygamie », Revue des droits de l’homme n°19, 2021 [online].

« Le “blackface” d’Antoine Griezmann indigne, il s’excuse et retire la photo », Huffington Post, 17 December 2017 [online].

Françoise Vergès, « Comme Michel Leeb, les racistes non racistes refusent de comprendre ce qu’est le racisme », Le Monde, 13 December 2017 [online].

« Placé déplore l’imitation “pas drôle” de Canteloup », Dernières Nouvelles d’Alsace, 21 September 2014 [online].

Like Thomas Kuhn’s paradigm, myths act like filters: they retain confirmatory elements and discards discordant ones.

The myth of structural racism leads to over-interpretation. Secularism is seen as racist because it is deemed hostile to public manifestations of religious identities, which minorities are presumed to have a vital need for. The concept of “indirect discrimination”, borrowed from Canadian case law to mean that a uniform rule discriminates against minorities, establishes a formidable logic. It results in labelling as racist any rule devised by the majority population, and even any cultural tradition (for instance public holidays or food preferences).

Racism is supposed to lurk in any restriction on immigration, or in differential treatment between nationals and foreigners, as though nationality were a racial criterion. Criticism of Islam, for example, has led to accusations of “anti-Muslim racism”. Anti-racist laws have themselves been accused of racism,88 as have refusals to grant naturalisation in cases of polygamy.89

Many phenomena are interpreted without proof in terms of racism. Was footballer Antoine Griezmann’s blackface a racist act or a tribute to the famous Harlem Globetrotters?90 Is the imitation of an African accent in Michel Leeb’s sketch L’Africain, now denounced as racist, fundamentally different from mockery of Belgian, Swiss or Corsican accents? 91 It is not the case when this accent is used by Black artists, as in the case of Les Inconnus. Just recently, comedian Nicolas Canteloup imitated an Asian accent to mock Jean-Vincent Placé92 and Jean-Luc Mélenchon even used a southern French accent to mock a journalist.93

Zeev Sternhell, « Les origines intellectuelles du racisme en France », L’Histoire, n°. 17, November 1979 [online].

Carole Reynaud-Parigot, La République raciale (1860-1930), PUF, 17 February 2006.

Yaël Brinbaum, Géraldine Farges and Élise Tenret, « Les trajectoires scolaires des élèves issus de l’immigration selon le genre et l’origine : quelles évolutions ? », CNESCO, September 2016 [online].

Yaël Brinbaum and Annick Kieffer, « Les scolarités des enfants d’immigrés de la sixième au baccalauréat : différenciation et polarisation des parcours », Population, vol. 64, n°3, 2009 [online].

Luc Behaghel, Bruno Crépon and Thomas Le Barbanchon, « Évaluation de l’impact du CV anonyme », Paris School of Economics – Inra, Crest and J-PAL Europe, 31 March 2011 [online]. See also Alain Lacroux and Christelle Martin-Lacroux, « Quelle efficacité pour le CV anonyme? Les leçons d’une étude expérimentale », Revue de gestion des ressources humaines, 2017, n°104.

Revisiting the work of past authors can give the impression that racism has been omnipresent in French history. But this rereading is often taken out of context and tends to exaggerate the influence of the discourse. Sensitive to scholarly rigor, academics tend to unearth forgotten authors to whom they attribute great influence, without taking concrete policies into account. In support of his thesis on the “French origins of racism”, Zeev Sternhell claims to have discovered “a very vast movement of thought which, although it did not produce a structured political organisation in France, nonetheless profoundly permeated the intellectual atmosphere”.94 But can a “vast movement of thought” be devoid of the slightest political outlet? Similarly, if the Third Republic really was imbued with a “racial paradigm”, as one historian maintains, why did the legislation bear no trace of it?95

Sociological analysis is no more satisfying as arguments often remain superficial. The desire to validate the thesis of structural racism leads to any statistical discrepancy being interpreted as proof, or to phenomena such as discrimination or police stop-and-searches being blamed on racism.

But all these elements are more indicative of a confirmation bias than authentic proof. This brings us back to Thomas Kuhn’s concept of a paradigm: the myth becomes a hermetic belief that dismisses conflicting facts and overinterprets supposed confirming evidence.

Statistical gaps based on origin (for example in academic achievement, access to employment, social or health problems, early mortality, etc.) are not in themselves proof of malicious mechanisms of domination or exclusion. As for calls for testimonies regarding discrimination, they consitute fragile evidence: anyone can interpret a school or professisonal failure through the lens of discrimination, especially when one can claim prejudice in court. Feelings, however, are not necessarily a reliable indicator. This is not to deny the existence of discrimination, but rather to recall that it is also stems from regulations, even when these are intended to be benevolent and protective. In a country that intends to protect employees and tenants, it is logical that employers and landlords should be particularly cautious when making selections, to the detriment of groups that are subject to suspicion or uncertainty (which includes, for example, young people or people who are overweight).

Moreover, research has suggested that the scale of discrimination should be put into perspective,going so far as to imply to opposite conclusions.96 For example, it has been shown that for the same social background, children from immigrant families receive more leniency when advancing to the second year of secondary school.97 Experimental studies support this direction: they confirm LaPiere’s conclusions by demonstrating that declared discrimination does not reflect actual practices: if anonymous CVs were abandoned, it is because experiments showed that discrimination is weaker when employers know the origin of individuals.98 The anonymous CV would be a good solution if society were structurally racist; but if this is not the case, it becomes an obstacle by preventing recruiters from exercising the goodwill they show towards minorities.

As for so-called “racial profiling” checks, which are supposed to provide proof of structural racism within the police, they are hardly conclusive in the absence of data on delinquency and incivility rates according to origins. Police officers have practical knowledge that leads them to prioritize risk factors. A study conducted in Paris in 2009, the most thourough to date, showed that checks vary according to a number of parameters: location, gender, age, or clothing.99 Furthermore, this study did not take into account other factors such as suspicious behavior, the presence of a crowd or gathering of people, crime-prone areas, and so on.

Reductionism

Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau, La race prussienne, Librairie Hachette & Cie, 1871.

Stéphane Strowski, Les Bretons: essai de psychologie et de caractériologie provinciales, Rennes, 1952.

Henri Tajfelet al, “Social categorization and intergroup behaviour”, European Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 1, issue2, 1971 [online].

« Pendez les Blancs : le rappeur Nick Conrad relaxé en appel pour vice de procédure », Le Parisien, 23 September 2021 [online].

Norbert Elias and John Scotson, Logiques de l’exclusion, Fayard, 17 September 1997

Pierre Bourdieu et al, « Classe contre classe: de l’existence d’un racisme social », Différence, n°24-25, July 1983, quoted in Interventions 1961-2001, Agone, 2002.

Myth is like a spotlight: it illuminates as much as it obscures. While structural racism has the advantage of providing a reassuring explanation, it has the disadvantage of interrupting reflection. Its message is reduced to a moral injunction: we must fight racism and prejudice because it is possible to eradicate all these phenomena. This injunction is understandable from a human point of view, but reflection cannot be confined to this moral stance.

The myth of structural racism is reductionist as it confines racism to the attitude of the White majority towards ethnic minorities. However, racism is neither a recent phenomenon, nor a Western specificity. It is a reality far older and more universal, related to the propensity of each human group to believe that there are natural differences between itself and others, particularly its enemies, to whom all the faults of the earth are attributed. This is why the term race was once used to refer to the “Prussian race”100 or the “Breton race”.101

This disconnection from physical traits is unsurprising, as race is primarily a social construct, meaning that it depends primarily on sociopolitical parameters. The 1994 genocide of the Tutsis by the Hutus demonstrated this, while interethnic wars in Africa or elsewhere, as well as the various rivalries across the globe (between Flemings and Walloons, Quebecers and Canadians, Czechs and Slovaks, Catalans and Castilians, etc.) confirm that identity conflicts are not limited to skin colour.

The distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’ is a universal trait that can emerge even in the absence of competition for resources.102 Every group creates its own derogatory vocabulary to refer to those outside it. The French spoke of « Boches », « Ritals » or « Rosbifs »; and they refer to themselves as « Zoreils » on Reunion Island, « Popa’a » in Polynesia, « Békés » in the West Indies or « Gadjé » (the Gypsies). Hatred itself seems universal, even if the hypothesis of “anti-White” racism is hard to fathom, even when it arises in a video clip calling for “hanging Whites”.103 Physiological and physical traits may reinforce this phenomenon, but they do not create it. Racism exists without race, as Norbert Elias asserted when studying social relations in a small English town where the ‘Established’ set out to distinguish themselves from the ‘Outsiders’.104

From this perspective, it is not wrong to say that racism has a structural dimension – provided we remember that all human groups are concerned. In this respect, Michel Foucault was right: race is probably a constitutive element of all human societies, whether the aim is to differentiate between groups or to distinguish an elite with qualities deemed superior. “There is not one racism, but many racisms”, said Pierre Bourdieu, pointing to the “racism of intelligence” as a form of “class racism”.105

What Michel Foucault failed to see, however, was that the French miracle lies precisely in having prevented this elementary psychosocial tendency from becoming a social practice or an institutional norm – unlike in the United States, where racism was incorporated into legislation for several decades. In France, race has neither governed the legal and institutional order, nor shaped the ethos of the elites or of the broader population.

Blindness

Nonna Mayer, « Une approche psycho-politique du racisme », Revue française de sociologie, 37, 1996

[online].

See Laurent Cordonier, La nature du social. L’apport ignoré des sciences cognitives, PUF, 2018 [online]; See also Bernard Lahire, « Eux/nous : ethnocentrisme, racismes », in Les structures fondamentales des sociétés humaines, Bernard Lahire, La Découverte, 2023.

Rob Henderson, “‘Luxury beliefs’ are the latest status symbol for rich Americans”, New York Post, 17 August 2019 [online].

By adopting as its ideal a world free of racism and discrimination, the myth of structural racism refuses to acknowledge that discrimination stems from a universal inclination to favour members of one’s own group (ingroup) over outsiders (outgroup). 106

In every human community, there is a preference for similarity and a corresponding distrust of difference.107 Discrimination is part of the basic logic of social life. It reflects the desire to make one’s environment feel secure. Everyone seeks to reassurance by favouring those who resemble them – whether in everyday life or in their professional environment.

One could draw here on the expression “sphere of recognition” proposed by the sociologist Axel Honneth. Human groups live in environments where ways of being and behaving form shared codes of mutual recognition – language, rules of politeness, food preferences, notions of the sacred, historical references, and so on. These codes send reassuring signals, serving to foster a soothing environment for individuals.

These affinity-based mechanisms are powerful. The phenomenon of diasporas or the segmentation observed on social media – giving rise to bubbles of like-mindedness – are evidence of this. Wealthier segments of the population go to great lengths to ensure the best possible social and educational environment for their children, even if it means setting aside their “luxurious beliefs” about the benefits of diversity.108 Even students, typically very concerned about tolerance and openness, tend to group by nationality when participating in international exchange programmes. It is also well known that in assisted reproductive treatment, racial matching is often requested or favoured by doctors, even though French law does not require it, unlike in Great Britain.109

Proponents of structural racism remain blind to this reality. They identify only those discriminatory practices that emanate from the majority towards minorities; while other forms of discrimination – between minority groups or from minorities towrads the majority – are rarely mentioned, studied, or condemned.110

Discrimination itself is often analysed in a superficial manner. It is typically explained as stemming from prejudice against minorities, without acknowledging that prejudices are shaped through interactions and are not always irrational.

The nature and extent of discrimination can, of course, vary. But the more diverse societies become, the more discrimination tends to increase. It is precisely because French society has become more ethnically and religiously diverse that discrimination has been put on the political agenda – a topic that was largely absent in earlier decades.

One of the blind spots of the systemic racism narrative is its lack of reflection on the implications of increasingly diverse societies. The challenges posed by this diversification are considerable. Can a diverse society succeed in creating a shared civic space? Can it establish a consensual political representation that is not a source of frustration for a part of the population? Is it possible to live under a common legal framework? Can there even be a unified national memory – with shared legends and heroes – and, by extension, uniform school curricula suitable for all of society?