Western Sahara: questioning the theory of moroccan infringement

Timeline

Index of acronyms

Introduction

An unusual case of decolonisation

The Sharifian Empire and its unique political grammar

A late and peculiar colonisation process and model

Borders, an unresolved issue at independence

The patchwork of Spanish possessions

Independence in stages

The ‘three ages’ of international law

The coronation of sovereignty (1648-1945)

Priority given to stability and prohibition of annexations (1945 to the present day)

Self‑determination as a mean for decolonisation

Evaluating the green march

The ‘pre-history’ of the Green March

The scope of the Green March

War and the diversification of legal sources

The position of the International Court of Justice

The Security Council enters the scene

Security Council resolutions

Phases of the conflict

Moroccan inflections

Ceasefire and preparations for a referendum

Mohammed VI, development and the autonomy plan

From legal polycentrism to tokens55

Legal guerrilla warfare in Luxembourg

A judicial intrusion into foreign policy

The Court’s judgments in relation to European law

Court rulings with regard to international law

Towards a resolution of the conflict

The argument of ‘historical rights’: advantages and constraints for Morocco

Advantages and disadvantages of legal avoidance for France

Enriching the Moroccan reference framework

Fairness and legality

Conclusion

A former student of ENA and lecturer at Sciences Po, Dominique Bocquet is writing a book on the Western Sahara conflict. He has served as an advisor to Hubert Védrine and was Head of the economic department at the French Embassy in Morocco. He is a Senior Fellow at the Policy Centre for the New South in Rabat. This report was prepared at the request of Dominique Reynié, Director General of Fondapol, and written on behalf of the foundation.

Sâ Benjamin Traoré is a professor of public international law. He defended his doctoral thesis entitled ‘The Interpretation of United Nations Security Council Resolutions: A Contribution to the Theory of Interpretation in International Society’ at the Faculty of Law of the University of Neuchâtel. He teaches at Mohammed VI University in Rabat.

Summary

For 50 years, the Western Sahara conflict has been pending before the international fora.

In 1975, Morocco claimed sovereignty over this vast desert territory – which had previously been a Spanish colony – as it considered this territory had previously belonged to her. This view is contested by the Polisario Front, an independence movement supported by Algeria. The international community has adopted an ambivalent attitude, accepting the idea that Morocco has violated international law, while at the same time becoming increasingly conciliatory towards Morocco, which exercises de facto sovereignty over the aforementioned regions.

This ambivalence creates a situation that is difficult to understand and untangle.

This report examines the origins of the antagonism between Algeria and Morocco, as well as the geography and history of Western Sahara. It revisits the theory of Moroccan violation through a re-reading of applicable international law. It advocates overcoming the conflict by addressing its root causes.

Dominique Bocquet,

Former student of ENA and lecturer at Sciences Po Paris

with Sâ Benjamin Traoré,

Professor of Public International Law

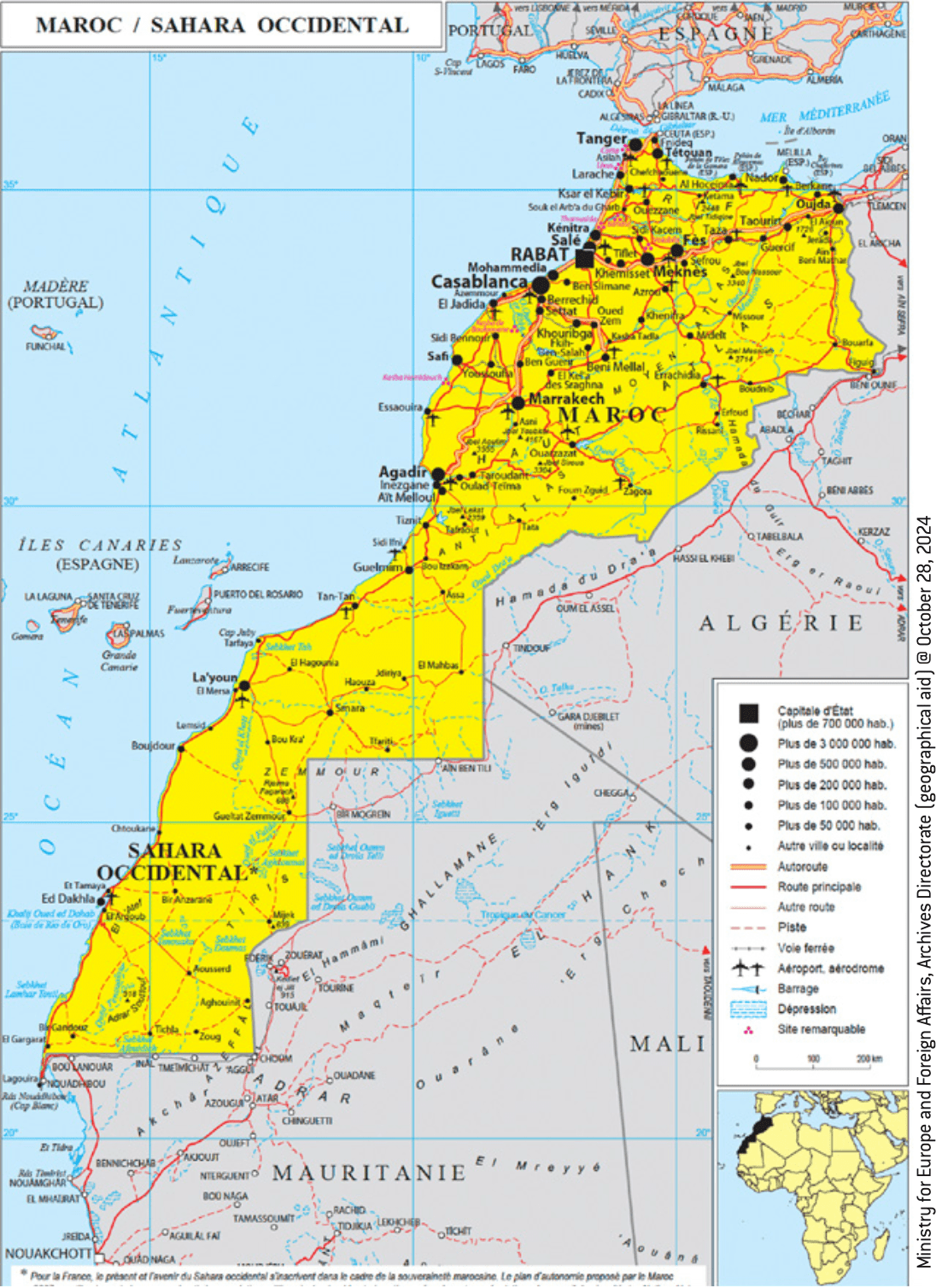

Map of Morocco featured on the official website of the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs since October 2024

Source :

France Diplomacy, Presentation of Morocco [online].

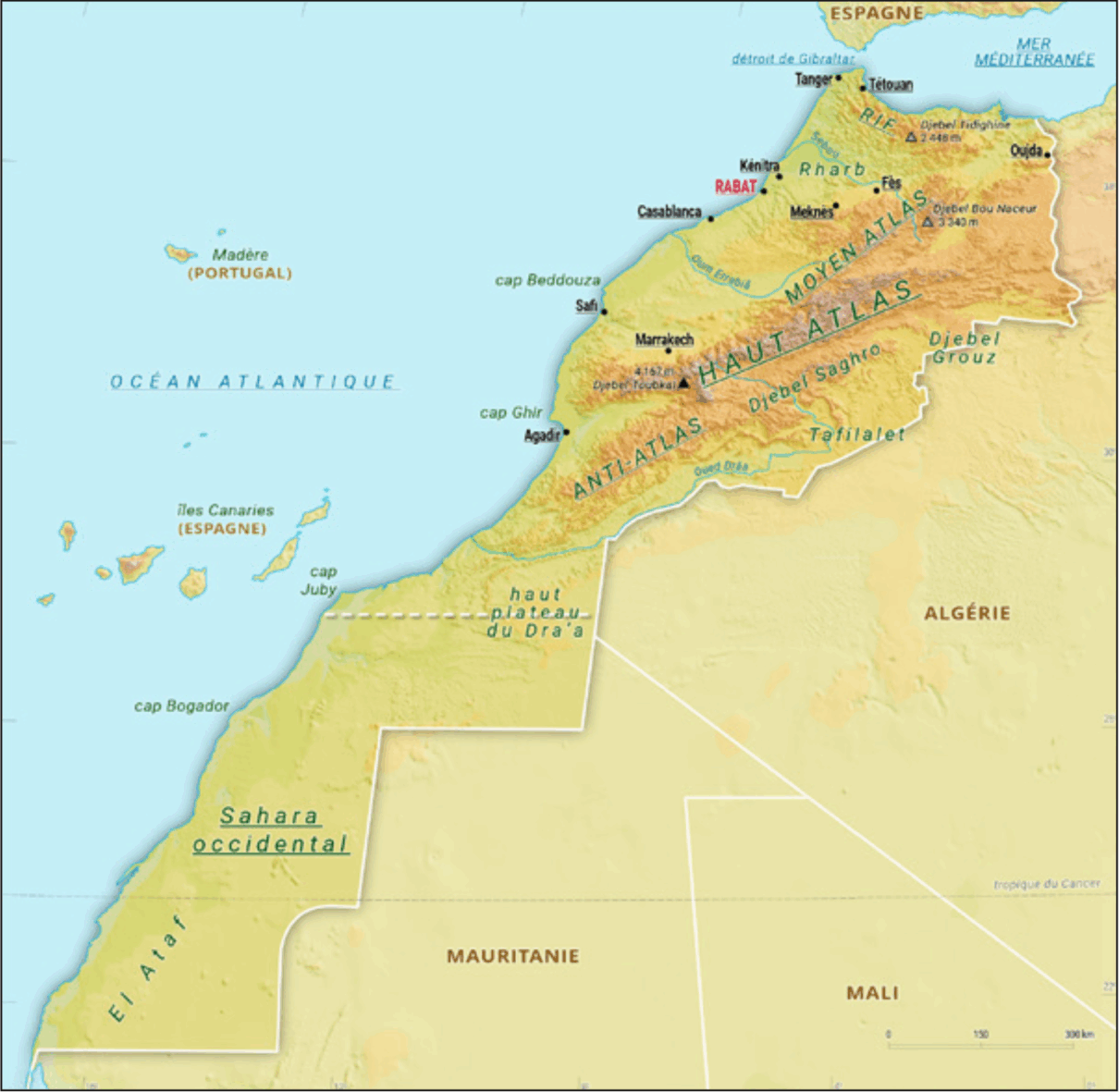

Map of Greater Morocco published in 1956 by the Istiqlal party

Source :

Press conference of Allal El Fassi, Cairo, July 4, 1956.

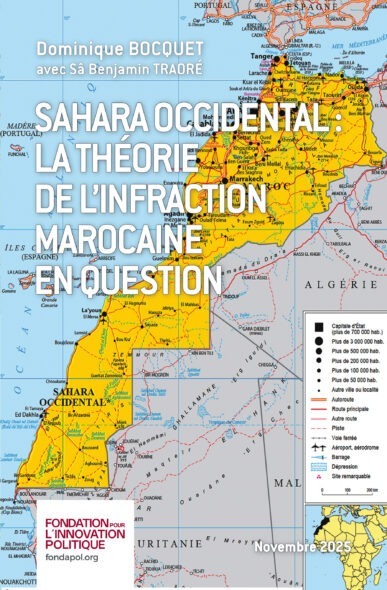

Universalis map 2025

Source :

Universalis, Physical Map of Morocco [online].

1884: the Spanish gain control of Rio de Oro (southern part of Western Sahara).

1912: the Treaty of Fez establishes the Franco-Spanish Protectorate in Morocco.

1920: the Spanish gain control of Saqia El Hamra (northern part of Western Sahara).

1956: the Protectorate ends and Morocco becomes independent. Spain retains Western Sahara, Tarfaya, Ifni, etc.

1957-1958: the Moroccan Army of Liberation takes action in Western Sahara and Mauritania, French reaction (Écouvillon).

1958: the Tarfaya strip returns to Morocco.

1963-1966: the case of Ifni and Western Sahara is raised at the UN. They are then added to the list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.

1969: the city of Ifni is returned by Spain to Morocco.

1972: demonstration in Tan-Tan (Morocco) in favour of the reunification of Western Sahara with Morocco.

29 April 1973: the Polisario Front is founded in Zouerate (Mauritania).

6 November 1975: Green March (350,000 Moroccan civilians enter Western Sahara).

14 November 1975: Madrid Accords, division of Western Sahara (Morocco-Mauritania).

27 February 1976: the Polisario Front proclaims the SADR with the support of Algeria.

1976-1980: the Polisario attacks the Moroccan and Mauritanian armies, refugees in Tindouf.

1979: Mauritania evacuates Western Sahara, Morocco enters.

1981: Hassan II raises the possibility of a referendum.

1982: the SADR is admitted to the OAU.

1984: Hassan II commits to the referendum at the UN (September);

Morocco leaves the OAU (November).

1991: a ceasefire is signed and the UN Security Council establishes the MINURSO (6 September)

2006: Mohammed VI announces an internal autonomy plan.

2007: the UN Security Council welcomes proposed autonomy plan as ‘serious basis for negotiation’.

2017: Morocco rejoins OAU (now African Union) without precondition of SADR exclusion 2020: ‘Abraham Accords’ and US recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Sahara.

2022: Spain declares the autonomy plan to be the ‘most serious and credible basis’ for a settlement.

2024: Letter from President Macron to the King (Moroccan sovereignty ‘present and future’ in the Sahara).

2025: 50th anniversary of the Green March (6 November).

Index of acronyms

AU: African Union (since 2002)

CJEU: Court of Justice of the European Union (Luxembourg)

CORCAS: Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs

EU: European Union

FAR: Royal Moroccan Armed Forces

FLN: National Liberation Front (Algeria)

GPRA: Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic

ICJ: International Court of Justice (The Hague)

Istiqlal: Independence Party (Morocco)

MINURSO: United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara

NSGT: Non-Self-Governing Territories (UN list)

OAU: Organization of African Unity (1963-2002)

OCP: Sharifian Office of Phosphates

Polisario: Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Rio de Oro

SADR: Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

UN: United Nations

UNFP: National Union of Popular Forces

UNGA : United Nations General Assembly

UNSC: United Nations Security Council

USFP: Socialist Union of Popular Forces

Karim El Aynaoui kindly shared with me, in a spirit of mutual independence, his personal insights into the causes of the conflict. The role of revolutionism as an ideological determinant was one of them.

Half a century ago, Morocco asserted its sovereignty over Western Sahara, previously occupied by Spain. On 6th November 1975, a crowd of 350,000 Moroccans, led by King Hassan II, entered the territory, forcing Madrid to negotiate. Despite the desert nature of this vast territory, mainly inhabited by nomads, a conflict arose and remains unresolved fifty years later. Its ins and outs remain a mystery.

As countries that have long been associated with the Moroccan cause, France and Spain are in a difficult position, for, on the one hand, both countries see Moroccan sovereignty over this territory as effective and legitimate, while, on the other hand, they refrain from declaring it legal.

Legal uncertainty created by non-recognition is a hindrance to business, a brake on investment and an obstacle to development. It allows the Polisario Front, an armed movement supported by Algeria, to claim independence in the name of international law.

How can this imbroglio be resolved? The answer is political, but not solely so. Morocco is scoring decisive points politically. Its diplomacy has become more effective. The circle of countries supporting her is widening. The Security Council increasingly recognises the autonomy of the territory as the most serious basis for settlement, to the detriment of the independence thesis.

However, legally, Western Sahara remains a ‘non-self-governing territory’. The list is drawn up not by the UN Security Council but by the UN General Assembly, which has jurisdiction over decolonisation. Classifying the territory as non-decolonised amounts to challenging Moroccan sovereignty. The right to self‑determination is invoked to accuse Rabat of violating international law. Another aspect is the ‘intangibility of borders inherited from decolonisation’, a concept specific to Africa which prohibits any modification of borders, even through negotiation. Morocco is said to have violated this prohibition by erasing its border with the former Spanish Sahara. With this argument, the Polisario and Algeria secured admission for the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) to the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1982.

What are these arguments worth? Surprisingly, they have been little contradicted in public debate. The tactic initially used by Morocco and France is not unrelated to this. It consisted of sidestepping a biased legal debate. 1975 was a pivotal year. Back then, a revolutionary ideology demonising the regime of Hassan II and glorifying armed liberation movements was especially pervasive in the international fora.3 The West was intimidated and Morocco was pre-emptively condemned.

Inevitable in the short term, this legal avoidance was bound to have major consequences on the intellectual debate: it gave the impression of a guilty plea. Since it was little criticised in the public discourse, the thesis of ‘Moroccan infringement’ of international law appeared unequivocal, even to those who felt sympathy towards the country.

Today, if the French and Spanish do not address the legal issue at its root, Morocco’s success will be presented by some as a setback for the law and a fait accompli. Is this a good outcome for the law? Is it the best outcome for Morocco? Is it a positive outcome for the other parties involved (including Algeria)? This study highlights the weaknesses of the initial international resolutions and invites researchers to reinterpret them.

In other words, an opaque block whose results we are asked to accept without any right to scrutinise how they were arrived at.

| Methodology of the report

This report focuses on the main points of reasoning. It does not claim to list all the facts, but strives to restore the nuances that have been lost in a Manichean debate, which has largely contributed to this image of a frozen conflict. It focuses on the spirit of the law and its interaction with the historical and geographical context. This would not have been possible without the help of Professor Sâ Benjamin Traoré. His thesis on The Interpretation of Security Council Decisions, defended in Neuchâtel, is authoritative. He kindly engaged in extensive discussions to facilitate the drafting of this text and then reread it carefully. This report owes him a great deal. In the case of Western Sahara, international law was often invoked as a black box.4 Drawing on Professor Sä Benjamin Traoré’s reflections on interpretation (in general) and the Sahara (in particular), I propose the opposite to the reader: to open the bonnet of the engine and show how this law works. |

PART 1

The formation of the legal knot

An unusual case of decolonisation

This angle of analysis was suggested to me by Sâ Benjamin Traoré. His perception as a lawyer well versed in decolonisation issues converged, on this point, with my historical research on the notion of ‘Moroccan singularity’. See Dominique Bocquet’s article, ‘Moroccan Singularities and French Perplexities,’ Commentaire, issue 182 (Summer 2023) [online].

The method of analysing international relations advocated by Raymond Aron has sometimes been defined, in formal language, as ‘idiosyncratic realism’.

If the Western Sahara issue appears indecipherable, it is because its history and specific characteristics have been erased. It was believed to be a classic case of decolonisation. On the contrary, it was rather atypical.5 We must accept this complexity if we want to shed light on a subject that simplification can only distort.

Everything about this issue is atypical. First, there is the history of Morocco, a thousand-year-old empire with a unique political structure in the world. Then there is its strategy of decolonisation, independence in stages rather than all at once. Finally, there is the ‘nature’ of Western Sahara: a territory that is more desert-like than Patagonia and only crossed by nomads.

The history of Moroccan-Algerian relations is worth mentioning. While Algeria is officially only a third party as it has no territorial claims and only a very limited common border with Western Sahara, it is cited in the proceedings as ‘interested in the conflict’, an unusual qualifier in international law, even for a neighbouring country.

We shall start by discussing these specificities, bearing in mind Raymond Aron’s methodological argument that each situation must be studied on its own terms, outside pre-established frameworks.6

The Sharifian Empire and its unique political grammar

This proposal was rejected. The Sultan was a notorious polygamist. The King of France did not want to see his daughter in a harem. Nevertheless, bilateral relations (established since at least the reign of Francis I) were revived.

Morocco is not a ‘standard’ case of decolonisation.

In sub‑Saharan Africa, colonisers often arrived in the 19th century in regions marked by linguistic and ethnic fragmentation. The question of whether or not a State already existed remains controversial. What is certain, however, is that it was not present everywhere and that tribal logic continued to play a predominant role. In this context, colonisers are often considered to have promoted the notion of the modern State through ‘colonial states’, which would later serve as the foundation for independence.

In North Africa, large entities existed and linguistic diversity was limited (Arabic dialects and Berber languages). In Morocco, colonisation found a pre-existing State: a thousand years old, with trade relations on several continents and embassies in Europe.

Independence was embodied by a Sultan, endowed with religious legitimacy as ‘Commander of the Faithful’. His role was to defend the country, particularly against Spain. For eight centuries (8th-15th centuries), Muslims and Christians had shared the Iberian Peninsula, engaging in deep interaction interspersed with wars. We remember the wars, but we have forgotten the interaction. Despite the cruel expulsion of Muslims and Jews at the end of the 15th century, Spain is the European country with the strongest Arab-Muslim cultural influence. Conversely, the influx of Andalusians made Morocco the southern Mediterranean country most familiar with the Christian West.

Spain was then the world’s leading power. It was this empire (admittedly monopolised in the 16th century by the conquest of America) and the Ottoman Empire (present as far as Algeria) that the Moroccans resisted. Their method was to unite behind the Sultan when their land was attacked. In addition, in the 17th century, the army was reorganised by Sultan Moulay Ismaël, one of the first of the current Alawite dynasty, and gained a reputation for invincibility that lasted for several centuries.

Sultan Moulay Ismaël sought the hand of one of Louis XIV’s daughters in marriage. France indeed appeared to be Spain’s rival. There was a convergence of interests and also the seeds of an elective relationship before the colonial episode. This was Morocco’s second significant link with Europe.7

The sultans were not European-style kings, relying on a feudal hierarchy and seeking cultural and administrative unification. Except in times of war, their role was limited. The country was dominated locally by tribes. The tribal nature of the Maghreb was counterbalanced by tangible factors of unity (languages, religion, etc.). Nevertheless, conflicts remained numerous, to such an extent that a traditional distinction was made between the ‘bled makhzen’, the part of the country that regularly paid taxes to the Sultan, and the ‘bled siba’, the more rebellious part, where the Sultan had to wage war to obtain his tribute.

The relationship with the Sultan was one of allegiance. Allegiance is a symbolically important bond, formalised by written oaths. It is part of the Moroccan legal corpus. It guarantees solidarity in the face of external enemies but does not imply absolute obedience in all areas. Hence the term Sharifian ‘empire’ (rather than ‘kingdom’), which was used until the 1950s to refer to Morocco.

A late and peculiar colonisation process and model

Journal official de la République française, 27th July 1912, Decree of 20 July 1912, Publication of the Treaty of Fez, 30 March 1912, relating to the organisation of the French protectorate in Morocco [online].

Conversation with Mehdi Benomar, Director of Research at the PCNS.

For Pascal Ory, ‘the presence of a local legal institution, in the case of French North Africa, Morocco and Tunisia, completely changes the identity data’, Qu’est-ce qu’une nation ?, Gallimard, 2020, p. 68.

French diplomat, Resident-General of France in Tunisia (1882–1886).

With one major difficulty during the Hassan II period: the lack of high-level executives, an area in which Morocco has made enormous progress since then.

The first major Alawite defeat came in 1844, against France, which was completing its conquest of Algeria. France forcibly prevented the Sultan from supporting Algerian tribal rebellions against it. But the sovereign retained considerable military capabilities. Paris did not venture to conquer the country. However, the latter continued to weaken due to widespread internal anarchy (the Sultan having to fight on several fronts) and persistent archaism in the face of a Europe in full economic ascent and tending towards imperialism.

In 1912, when the monarchy was ready to compromise on sovereignty, it was too late for France to commit significant military resources given the increasingly tense military situation in Europe. The same context prevented her from imposing herself alone in Morocco. The Protectorate was thus established by the Treaty of Fez on 30 March 1912.8 The territory was divided: Spain was given back control of part of the Protectorate while also retaining possessions outside its perimeter.

If the texts emphasised the unity of the country, reality suggested otherwise and the duality of colonial powers proved to be a source of disunity. This partially centrifugal effect of colonisation is another specific feature of Morocco: it is the opposite of the strongly centripetal dynamic often observed in sub‑Saharan Africa during colonisation.9 This is not a minor point: if Western Sahara had had the same coloniser as the regions further north, would anyone have considered for a moment that it might have a future separate from Morocco? Added to this is the multiplicityo f statuses among the territories under Spanish colonisation. Sacralising the borders inherited from colonisation is a premise that is hardly acceptable to Moroccans.

In 1912, Morocco’s military capabilities forced France to compromise, establishing a protectorate that was defined as temporary and allowing the monarchy to remain in place. The preservation of a national institution (as in Tunisia with the Bey) represented a major difference from the legal status of Algeria, which was considered an integral part of French territory.10 General Hubert Lyautey, a romantic military man, fond of tradition and an admirer of the Maghreb, was the right man for the job. The first Resident-General saw himself as serving the Sultan. Waging war in his name against rebel tribes, he unified or ‘pacified’ the country.

During his lifetime, he did his utmost to curb the abuses associated with colonisation, abuses he had observed during a previous stay in Algeria. Like Paul Cambon,11 who had preceded him in Tunisia, his obsession was ‘not to repeat French Algeria’. Nevertheless, he set up a colonial State apparatus, with a developmentalist purpose, certainly, but with a Jacobin spirit.

After Morocco’s independence, this apparatus was taken over and completed, then brought closer to the model of the modern ‘Weberian’ State.12 This model did not fit in with traditional Sharifian governance, which was extremely flexible. This is one of the reasons why Hassan II, a strong-willed ruler who came to the throne in 1961, was described as a ‘tyrant’ by some of his opponents, and one of the reasons for the upheavals in Morocco in the 1960s and 1970s, when the drama of Western Sahara unfolded. These upheavals also reflected the emergence of new forces with the civic engagement of the middle and upper classes. The struggle for independence had been the crucible for this, with the ‘national movement’ of the 1930s, which founded Morocco’s first political party, Istiqlal (‘independence’ in Arabic), in 1943. This civic action was crucial, not only for independence, but also for the emergence of a political space and an articulated national consciousness in Morocco. Istiqlal split in two in 1959 (Istiqlal ‘remained’ in the centre-right, and the National Union of Popular Forces – UNFP, a left-wing party that became the Socialist Union of Popular Forces – USFP in 1975). This was rather healthy: with independence, new parties emerged and, with them, a form of political diversity.

The monarchy therefore had to contend with modern political forces. Initially, those political forces had military units founded during and for the struggle for independence, whereas Sultan Mohammed V was unarmed, for defence had previously been the responsibility of the colonial powers under the Protectorate. One of his priorities was to create the Royal Armed Forces, with the help of France. He entrusted command to his eldest son, Prince Hassan.

When the latter became king upon his father’s death in 1961, the struggle for power became fierce. This explains (without excusing) the serious human rights violations that subsequently took place in a country that was generally concerned with tolerance and conciliation.

In 1961, the new king chose to preserve, ‘Moroccanise’ and develop the centralised, developmentalist State sketched out by the French. But he had the intelligence – rare at the time – to allow party pluralism to take hold. At the end of his reign, he restored flexibility to governance through a compromise with the national movement and its democratic demands. The political crisis was overcome by gradually allowing elected officials to play a role in managing the daily lives of Moroccans.

Hence, at the end of the 20th century, the emergence of a pattern of alternation in legislative elections: victory for the socialists in 1998, for the moderate Islamists in 2011, and their dismissal at the polls in 2021.

This led to the new profile of the sovereign embodied by Mohammed VI, who ascended to the throne in 1999: a king who remained the cornerstone of the system but who took as little part as possible in disputes, unlike his father, a sovereign who threw himself into the fray. The current king is committed to promoting a ‘vision’ for the country’s future. The term ‘vision’ (officially used) aims to add another quality to the traditional legitimacy of the monarchy: its concern for the country’s long-term interests.

This is the secret behind the ‘surprise’ felt by many at Morocco’s contemporary development: the negative feelings towards Hassan II’s repressive beginnings were by no means a sign of things to come. A country unlike any other, and already misunderstood (though slightly less so in France and Spain).

Borders, an unresolved issue at independence

An agreement on the demarcation of the border, putting an end to Morocco’s claims, was signed on 15 June 1972. Algeria ratified this agreement on 17 May 1973 and published it in her official gazette on 15 June of the same year. According to the UN, the ‘exchange of instruments of ratification’ took place on 14 May 1989. The Moroccan Parliament does not appear to have taken a position, at least not at that date. According to the Official Bulletin of the Kingdom of Morocco of 1 July 1992, the Convention was ‘made public’ on 22 June of that year.

According to some observers, Algeria initially sought to obtain for itself, within its territory, a corridor of access to the Atlantic, an ambition which she subsequently abandoned.

The Sharifian Empire had boundaries but no precisely defined borders, a concept that was adopted in Europe later than is commonly believed. Many other empires and states had been in the same situation. Consider, for example, the vagueness of the Roman Limes (even though the Romans were a highly organised people).

The Sultan’s sovereignty was traditionally based on the allegiance of tribes, some of which were nomadic and others turbulent. At independence, the absence of clearly defined borders became a headache. This was because, in the meantime, the concept had become widespread worldwide.

Due to its predominance in the Maghreb, French colonisation had little reason to push for the establishment of borders between countries: on both sides, the coloniser was often the same. However, a line approximately 120 km long, starting at the Mediterranean and running southwards, was drawn by France in 1845 to distinguish French Algeria from Morocco, which remained independent at the time. This line roughly corresponded to the former dividing lines between Moroccan and Turkish influences (the Regency of Algiers). It was hardly questioned thereafter. Further south, however, ‘the Algerian-Moroccan boundaries were vague’.

This vague definition allowed France, under pressure from its army in Algeria, to expand the territory controlled by the latter to the detriment of Morocco. The extent of this expansion is controversial, but its existence is undeniable. French archives are full of protests from French politicians against the encroachments demanded by the military, which were contrary to the obligations of the protectorate.

In 1961, with Algerian independence looming, Charles de Gaulle proposed to Mohammed V that the problems identified be resolved while the country was still under French sovereignty. Morocco, in solidarity with the Algerian struggle, consulted Ferhat Abbas’ Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA). In July 1961, an agreement was signed. The Algerian side undertook not to invoke the colonial border. Mohammed V did not follow up on de Gaulle’s offer. Alas! After independence and its seizure of power (1962), the FLN considered itself not bound by the GPRA’s commitments (the various commitments of the GPRA, not only those towards Morocco).

In 1963, a brief ‘Sand War’ ensued between the two countries. Despite Morocco’s superiority on the ground, Hassan II agreed to a return to the status quo in the disputed desert acres. Algeria had won a resounding political victory. Its diplomacy had succeeded in accrediting the thesis of an attack on its young independence and, better still, in rallying the rest of the world against Morocco, particularly sub‑Saharan Africa, which was concerned about the idea of border rectification.

The poison of mistrust had been instilled. On the Moroccan side, there was a sense of injustice. On the Algerian side, there was a sense of insecurity, stemming from doubts about the acceptance of its borders. Far from being temporary, as the Moroccans believe, these doubts would recur.13 This is one of the driving forces behind the conflict. Algiers’ subsequent involvement in the Western Sahara affair, a territory that it officially does not claim,14 stems in part from this concern. Whether justified or not, it made any means of exerting pressure on Morocco desirable for Algiers.

The patchwork of Spanish possessions

Treaty of Tordesillas, following the papal bull Inter cætera.

French historian born in Constantine, specialist in the Maghreb and the Algerian War.

‘66th anniversary of the National Revolution: message from the President of the Republic’, Algerian Embassy in France, 31 October 2020 [online]. See, for example, the statement made by President Tebboune on the 66th anniversary of independence. He refers to ‘an Algeria where every inch of land has been watered with the blood’ of martyrs.

As for Spanish possessions, the historical situation was full of paradoxes. After the discovery of America, Spain had little colonial ambition in Africa. It was absorbed by the New World. A division had been agreed with Portugal: Madrid would take western America, from the southern cone to Mexico; to Portugal, the East, i.e. Brazil and… Africa.15

However, this was only a partial satisfaction for Morocco because, due to its proximity (14 km across the Strait of Gibraltar), the few Spanish incursions into Africa were concentrated on it. But, second paradox, without much planning. No fewer than four different situations:

– the tiny Spanish enclaves on the Mediterranean coast (Ceuta, Melilla and a few islets). Appearing as early as the 15th century, they still exist in the 21st century, in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants to remain Spanish;

– a minority part of the ‘protectorate’. In 1912, France granted Spain control over part of the protectorate imposed on Morocco by the Treaty of Fez: Tetouan, part of the Tangier peninsula, the Mediterranean coast and the Rif. Hence the term ‘Franco-Spanish protectorate’. In 1956, this Spanish part returned to Moroccan sovereignty in the wake of the French withdrawal;

– Spanish possessions to the south, partly included in the protectorate, partly not included but enclaved within it, which Spain would only agree to relinquish after 1956: the Tarfaya Strip (1958), City of Ifni (1969);

– further south, the vast ‘Spanish Sahara’, retained by Francisco Franco until 1975.

South of the Spanish Sahara lies Mauritania, a State created by France and still marked today by a strong Moroccan cultural influence. To the west of Mauritania, Mali includes several regions that were, at certain times (long ago), part of the Sharifian Empire.

In addition, the Central Sahara had mainly been explored by the French. As Algeria was then perceived by Paris as destined to remain French forever, it was associated with that country (rather than with the French colonies in West Africa, for example). This led to a substantial increase in the size of the Algerian territory, which thus became the largest in Africa under colonisation. Despite the weight of her history, Morocco found herself with a neighbour five times its size. Its sense of territorial injustice could only be heightened, even coupled with concern in terms of geopolitical balance.

Conversely, one could deduce that Algeria was ‘saturated’, an expression once used by Chancellor Metternich (1821-1848) in reference to Austria. But in 1962, it began to see its situation differently. Towards the end of the war, believing that the FLN was dragging out the peace talks, Charles de Gaulle threatened to keep the central Sahara as a means of pressure. As a result, the Algerian leaders turned the territory into a symbol, a component of a ‘dearly paid’ independence, according to Benjamin Stora’s expression.16

To understand the orientations and vision of the Algerian leaders, it is necessary to decipher the language used to sanctify the territory: it invokes the blood of the martyrs of the struggle for independence.17 In other words, the magnitude of the sacrifices made prohibits, in their eyes, any questioning of the territory, which is seen as their fruit. Without wishing to be insistent, let us recall one element that may help us understand the Algerian point of view: if France expanded the territory of French Algeria as it did, it was because it considered it to be French ‘forever’. It was precisely this assumption that led it to refuse independence for so long, depriving Algerians of their civil rights and leading to bloodshed. Following this thread, we can see a link between the extent of the sacrifices and that of the territory: this initial belief in an Algeria that was ‘French forever’.

Let us go back to 1956, the year the protectorate was abolished. At that time, Morocco had only a reduced territory. Neither Spain, nor France, nor the Algerian GPRA of 1961 seriously disagreed with this. They did not subscribe to all the ‘rights’ invoked by Morocco, but few recognised none of them.

Independence in stages

Nizar Baraka, Secretary General of Istiqlal and Minister of Equipment and Water, introduced me to this concept. Larabi Jaïdi, Senior Fellow at PCNS, emphasises the importance of the border issue in the eyes of Moroccan historians.

Everything should have been laid out on the table. The international community could have recognised the problem of Morocco’s borders and sought a fair solution. As Moroccan historian Abdallah Laroui writes, a logical procedure would have been to hold an international conference to establish them within the framework of a balanced geopolitical vision. But this method, practised in the past, was no longer in keeping with the spirit of the times.

On the African continent, it would have been reminiscent of the colonial conferences of yesteryear, such as the Berlin Congress and others. To complicate matters further, the city of Tangier was under international status, with powers able to find opportunities there to extend their titles. Morocco did not want this. So there was no starting from scratch. Rabat was forced to improvise. It would be independence in stages.18 The road would prove to be fraught with pitfalls.

The Sultan took the precaution of stating the rights he considered his. Allal El-Fassi, leader of the Istiqlal, published a Map of Greater Morocco in March 1956 that caused a sensation. It encompassed not only the Spanish Sahara but also, for good measure, the whole of Mauritania, a large part of Algeria and part of Mali.

Intended to avoid the fait accompli of a diminished Morocco, the map could only cause concern among the countries concerned. Hence the first pitfall. This concern would above all poison relations with Algeria. But relations with Mauritania, which Morocco officially claimed until 1969, would not emerge unscathed. Rabat managed to establish friendly relations with Mauritania, but without completely dispelling Nouakchott’s concerns, with Algeria sometimes seen as a balancing factor.

The term ‘Moroccan expansionism’ became popular. The map was broad. Even within the Istiqlal party, many believe in hindsight that it was too extensive. To be fair, there was a dilemma: if it had been insufficient, it would have meant renouncing the territories not included. In short, there was no good solution, only a choice between pitfalls. Morocco remained calm, convinced of its rightful claim. However, the law in those days was fluid.

The ‘three ages’ of international law

To avoid repetition, this report uses the term ‘international law’ to refer to public international law. Private international law follows a different logic. Similarly, we sometimes refer to the Sahara to mean Western Sahara when the context is clear.

Raymond Aron expressed a certain scepticism about international law. The opposite view we express here is inspired by a conversation with Gilles Andréani, former head of the Centre for Analysis and Forecasting at the French Foreign Ministry and himself a great connoisseur of Aron’s thinking.

Public international law19 is not like other types of law: it depends on the agreement of States, the very subjects that it is supposed to bind. Hence its weakness and uneven application.

This leads some authors to doubt its reality. This is excessive: international obligations do exist, with a stabilising effect and reciprocity that encourages actors to comply with them.20 We simply need to remain clear-headed about the nature of these obligations and tirelessly return to the essential: the intention behind each provision. This will be our guiding principle.

To help understand the evolution of international law over the centuries, we offer a stylised interpretation. It deliberately simplifies its content by focusing on the main feature of each era.

The coronation of sovereignty (1648-1945)

The Treaties of Westphalia, concluded in 1648, ended the Thirty Years’ War and enshrined the affirmation of state sovereignty. They thus constitute a founding stage in the evolution of public international law and the principle of non-interference.

As Pierre Manent, philosopher and president of the Association des Amis de Raymond Aron, writes, the concept of ‘political form’ is an essential contribution to political science. It allows for the classification of different types of political organisation (Cours familier de philosophie politique, Gallimard, 2001).

The uti possidetis juris principle allows States to own the territories they hold, in order to avoid territorial disputes. This expression literally means: ‘You shall possess what you already possessed.’

Starting with the Treaties of Westphalia (1648),21 international law took shape, with the priority of consolidating the sovereignty of states. States gradually became the main political form, to the detriment of cities, tribes and empires.22 Modern State sovereignty requires precise boundaries. This has promoted the notion of borders.

In most countries, the sequence was first to assert de facto sovereignty through political and military power, and only then to potentially enshrine it in a treaty. In other words, the majority of borders in most countries around the world were the result of power relations, with a significant military component.

This point is worth reminding those who, assuming that Morocco had no rights to Spanish Sahara, conclude that it therefore scandalously abused its power.

Let us start, for a moment, from their assumption (which we do not share) about the absence of rights. In this scenario, what Morocco would have done is what many countries around the world have done, namely carve out a territory through the balance of power. Criticism in terms of current law is understandable, but there is a big difference between that and expressing it in grandiose terms.

Moreover, Morocco operated in a territory that was virtually uninhabited. To present it as having, in a manner of speaking, killed its father and mother is a discourse that can be held outside the realm of reality, in a particular forum heated by ideology. In France and Spain, countries familiar with Morocco, this type of exaggeration does not go down well.

Since its inception, international law has favoured the title of the last possessor (Uti possidetis juris23). As a result, so-called ‘historic’ rights, i.e. those based on the invocation of past sovereignty, are relativised. However, they were not completely disregarded: sometimes, states that were temporarily forced to yield to force claimed such rights (‘it was ours before’). They reserved the right to return to the fray, by force if necessary. Politically, historical rights often remained accepted.

Priority given to stability and prohibition of annexations (1945 to the present day)

After the catastrophes of the two world wars, the imperative of stabilising borders took precedence. This was the (natural) watchword of the victors. It became international law, especially since the two rival camps of the Cold War, the Atlantic Alliance and the Soviet bloc, shared this goal.

Hence the establishment of the UN Charter in 1945, which set out provisions for maintaining and restoring peace. The use of force was prohibited, except in self-defence, as were annexations. In fact, the latter became rare (without completely disappearing). The consequence this time was to truly turn our backs on the notion of historical rights, seen as a source of conflict. Priority would be given to the recognition of established and stable situations in the present.

This was a thorny issue for Morocco. However, it could plead the exception: its borders had not been stabilised (which was recognised). Consequently, its historical rights still had meaning. Moreover, colonisation had hindered their exercise. It could count on the help of a third right that was emerging, that of decolonisation. Unfortunately, its content would not fit well with Morocco’s specificities.

Self‑determination as a mean for decolonisation

Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, Resolution 1514 (XV) of the United Nations General Assembly adopted on 14 December 1960, United Nations [online].

Annuaire français de Droit international, quoted in the bibliography.

Incidentally, it allowed for cases where such consent was verified (e.g. the French overseas departments) to be dealt with.

United Nations, Resolution 2625 (XXV) of the United Nations General Assembly, entitled Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations; 24 October 1970 [online].

These terms are as follows: ‘to bring to a swift conclusion the process of decolonisation, taking due account of the freely expressed will of the peoples concerned.’

Policy Paper, The intangibility of African borders in the face of contemporary realities, PCNS, 2018, op. cit.

Another concern was to avoid any dismemberment initiated by the coloniser..

There are doubts about the validity of intangibility as a legal concept. In Africa, many borders were unclear. Can we freeze what we do not know? And forbid future generations from changing it?

This is how the secession of Eritrea from Ethiopia (1993) and then South Sudan from Sudan (2011) were accepted.

Even in Algeria, the Regency of Algiers was unified by the Turks several centuries before colonisation.

Loulichki, op. cit.

After developing countries joined the UN in the 1950s, the call for independence for colonies became irresistible. A specific right to decolonisation took shape.

This right had to take into account the principle of last possession (Uti possidetis juris). This principle could be used to perpetuate colonial rule. But it was impossible to go back on this principle, which was a ‘factor of peace’. There was no question of reforming ‘general’ international law in this way. That is why the law of decolonisation was to create an ad hoc framework.

Dilemmas of decolonisation and self‑determination

What should this special framework contain? One could have imagined emphasising historical rights, with the case of states that existed prior to colonisation: India, Egypt, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Morocco, etc. But in 1960, these countries were already independent. Attention was focused on the countries that remained to be decolonised.

In their case, recognising past rights seemed irrelevant. What about the form of statehood that was generally absent before colonisation, as was often the case in sub‑Saharan Africa? New blows were therefore dealt to the notion of historical rights, in favour of a progressive idea: self‑determination.

This notion was not new perse. It appeared in political philosophy as early as the 18th century, with Immanuel Kant. Its original meaning was the right of every subject, individual or collective, to determine their own destiny autonomously and freely. It began to emerge on the international stage in the 19th century with the welcome appearance of the notion of ‘the right of peoples to self‑determination’.

However, this was a very general principle. It was to be reconciled with other concepts, notably territorial integrity, which is essential to the stability of states. In other words, general international law did not enshrine the right of any population to secede from a state. A preliminary debate is required: how strong is the national claim and what is the relevant level for the exercise of sovereignty? Without this control, the principle would have been destabilising, contrary to the purpose of international law.

What was at stake here was to reconcile the right of peoples to self‑determination with the need for territorial integrity of states. The latter is a geopolitical necessity: to have viable states, capable of flourishing internationally, ideally with a balance between them.

It would be hypocritical to ignore this necessity in the name of democracy: it is not in the interest of the people to systematically favour small units over large ones. There are substantial advantages to belonging to a state of a certain size: its viability, the opportunities offered by a larger space, its influence abroad, etc. Wishes alone are not enough to justify secession; there must be a debate.

Providing material for debate does not weaken a principle, far from it. As early as the 19th century, nations with a clear identity broke away from multinational empires (Greece from Turkey, Italy from Austria). With the emergence of public opinion and intellectuals (such as Lord Byron), the rights of peoples and the principle of nationalities were able to exert an irresistible influence. However, this claim was very well supported. From 1960 onwards, a change took place: such a demand no longer seemed essential with regard to the coloniser.

Self‑determination, between principle and automatism

On 14 December 1960, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution that was to serve as the basis for the right to decolonisation: the famous Resolution 1514 or simply ‘1514’ on the ‘independence of colonised peoples’.24

In principle, the UN General Assembly does not have the power to enact binding norms. Some legal experts believe that it exceeded its authority. The legal scope of ‘1514’ could therefore be contested. However, we do not advocate this interpretation. Self‑determination represents progress, and decolonisation has been recognised as a competence of the General Assembly. For these reasons, the international community has validated the resolution, gradually but clearly. This is the argument put forward by Michel Virally.25 On the other hand, this process means that it must be seen as a (fundamental) principle and not as a rule to be followed blindly: its scope and modalities can legitimately be debated.

The enshrinement of the principle made it possible to address two problems.

The first was the risk of seeing the ‘right of the last owner’ invoked by the coloniser. Self‑determination removed this obstacle. Another concern was that colonisers claimed the consent of the people, an assertion that could not be verified. Self‑determination elegantly solved this problem by taking the colonial powers at their word.26

The day after Resolution 1514 was passed, the UN General Assembly adopted another resolution, 1541, dated 15 December. It specified that the decolonisation of a territory could take different forms, not just independence. Integration into an independent State is one of them. This allows the reunification of Western Sahara with Morocco to be seen as decolonisation and provides scope for historical rights. Furthermore, the General Assembly subsequently felt the need to revisit the issues raised in 1960. Resolution 2625 of 24 October 1970 emphasised territorial integrity.27 It emphasised the value of self‑determination but defended it in nuanced terms, far removed from any automatism.28

Nevertheless, the special procedure took on a life of its own. The Decolonisation Committee made self‑determination a rule, the verification of which depended on itself. It should be noted that a question should have been asked, but was hardly ever raised: could the right to self‑determination against the coloniser, for the reasons we have seen, be invoked in the same way against a country that was a ‘victim’ of colonisation? Was this really the original intention of the authors of the norm? This is a crucial question.

The intangibility of borders: a useful taboo and a questionable rule

In 1963, a legal ‘UFO’ landed on the African continent: the notion of the intangibility of borders inherited from colonisation. Intangibility means that borders cannot be touched, and therefore cannot be changed, even through negotiation and agreement. In other words, it goes so far as to prohibit discussion of possible rectifications. While negotiation is the very essence of international law, the possibility of it is excluded.

This strange concept was only introduced on the African continent. As Mohammed Loulichki has shown, stability does not require such a straitjacket. It only requires inviolability, the prohibition of modifying borders by force, a proven concept in international law.29

When Latin America achieved decolonisation in the early 19th century, Loulichki points out, it was the inviolability of borders that it proclaimed. In 1945, the same notion was enshrined in the UN Charter.30 Why did the OAU opt for such a drastic notion, closing the door to any negotiation?

There was an imperative: to consolidate the young states of sub‑Saharan Africa. The leaders of independence had chosen the colonial states as their foundations. These were sometimes artificial creations, overlooking tribal realities that were still very much alive. Destabilising the young states would have exacerbated Africa’s already considerable difficulties.

Freezing the borders was a way of setting the states within an untouchable perimeter. Intangibility was introduced in 1964 by an amendment to the OAU Charter. It is not essential for the legal protection of states against external attacks. Inviolability is sufficient. Intangibility makes it possible to combat centrifugal forces.31 In the name of this political necessity, it has severely restricted the expression of populations. It is for this reason that we use the word ‘taboo’ rather than ‘principle’, a term implying intrinsic justification: intangibility is not a fair concept. It is a prohibition deemed necessary.32

Its adoption had sparked bitter debate. One group of countries campaigned in its favour, the Monrovia Group. Another group campaigned against it: the Casablanca Group. The latter initially included Morocco, as the reader might expect, and Tunisia, as one might guess, since it had also suffered some encroachments. But it included another country: Algeria. Nevertheless, intangibility quickly became established after the creation of the OAU. Over time, it fulfilled its purpose: constant solidarity was shown in favour of sub‑Saharan states threatened with secession or annexation. Then, the taboo was eventually relaxed.33

In the absence of justification by ‘justice’, the intangibility of borders can only be accepted if it responds to an urgent need. This need does not exist at all in North Africa.

The existence of large entities was well established there (Egypt: several millennia, Morocco and Tunisia: around a millennium, Algeria: several centuries thanks to the Regency of Algiers).34 It is no coincidence that Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria initially found themselves together among the countries opposed to intangibility.

Morocco obviously aspired to groupings by comparison with the borders of the Protectorate. In its view, intangibility amounted to ‘accepting the consequences of colonial injustices’.35 It expressed reservations when this notion was added to the OAU Charter. As the latter has no normative power over its members, it cannot be legally opposed to Rabat. If we accept this point, a large part of the legal criticism against Morocco collapses. It is the least serious part, let us agree. Nevertheless, its futility (in the specific case of Western Sahara) has not prevented it from having an impact (on this same issue). Many have long believed that Morocco is in breach on this point. Their judgement on other points of law has been affected.

Intangibility has had a huge political impact in Africa: many sub‑Saharan states felt it was vital. Algeria, which benefited from territorial acquisitions under colonisation, rallied to this notion and brandished it before the sub‑Saharans. This was not unrelated to its political triumph in the ‘Sand War’. In the Western Sahara conflict, intangibility was invoked to add to the list of breaches attributed to Morocco. It contributed to the admission of the SADR to the OAU, an organisation that was supposed to admit only states. Elsewhere (UN, ICJ, other continents), the concept of intangibility has hardly been taken up.

Philosophically, intangibility and self‑determination are antinomic. The former restricts the latter: it prohibits populations that are divided into two or cut off from their roots from making claims. This calls for restraint in one’s stance. Blindly brandishing self‑determination is questionable, and doing so while glorifying intangibility is even more so.

Taken literally, intangibility limits self‑determination to a single possibility: demanding the departure of the coloniser within the territorial framework established by the latter. This is why the referendum seemed adequate, despite its limitations. We ended up forgetting another path: pluralistic elections and deliberation by elected bodies. These are more fruitful for democracy, as proven by India and South Africa.

Elections require pluralism, the establishment of institutions, the protection of freedoms, a civic culture – in short, laying the foundations for democracy. Referendums do not require this. They are suited to simple issues such as ending colonial dependence. They are a source of disappointment when it comes to deciding complex issues, in that it forces voters to decide without having all the facts at their disposal. As British historian Lord Acton wrote, referendums ‘separate decision-making from deliberation’. They are less faithful to the promise of democracy than we might think.

Geopolitically speaking, the coexistence of the concepts of self‑determination and intangibility is highly instructive. On the one hand, the right to self‑determination is proclaimed. On the other, intangibility introduces a safeguard. This is no coincidence. It confirms that self‑determination is rarely an absolute right, even in the case of sub‑Saharan decolonisation. It must be part of a balanced approach.

The fact that it is invoked against Morocco without any reservations or nuances is something of an exception. It is as if, because of its atypical nature, the Western Sahara issue finds itself in a blind spot of international law.

Evaluating the green march

The assertion of sovereignty over the Sahara is often presented as having begun with the ‘Green March’. This is an oversimplification. First, it is part of the general issue of Morocco’s borders (Spanish enclaves, border disputes with Algeria, etc.). Secondly, it has its own antecedents.

The ‘pre-history’ of the Green March

Reported by the Revue des Deux-Monde in 1960 and corroborated by Gilbert Meynier in his book Histoire intérieure du FLN (the latter did indeed face reprisals from Madrid). The context of Moroccan solidarity with Algeria and close ties between liberation armies made the FLN’s participation quite natural.

Abdallah Laroui cites the Republic of China and North Vietnam in this regard.

I must thank Fathallah Oulalou, economist and former USFP Minister of Finance, for sharing his invaluable experience. Among other things, he was El Ouali’s professor at the University of Rabat.

Driss Benhima introduced me to this literature, among other things.

Op. cit. The author is Sophie Caratini. The book was recommended to me by Mohamed Brick.

Issue examined in Pascal Ory, Qu’est-ce qu’une nation ? (What is a nation?) op. cit.

Georges Pompidou restored them after his election in 1969.

Western Sahara is located in a vast region of Moroccan influence that stretches from northern Morocco to Mauritania (inclusive). This influence can be seen in everyday objects, travel practices and prayer performed everywhere in the name of the Sultan, the only Muslim ruler in a region where the Ottoman Caliphate did not penetrate.

The Sultan collected oaths of allegiance from the tribes. According to Moroccan historian Abdallah Laroui, this is how he measured his sovereignty, while knowing that it was unevenly effective. The weakening of Morocco in the 19th century and the intervention of Spain in the 20th century in relations with the Sahrawi tribes are factors that have weakened ties.

Upon independence, Mohammed V reaffirmed ‘his rights’. At the same time, he refused to go to war with Spain (or France). At the time, the Istiqlal did not take the same line. However, this party had an army, the liberation army. In 1957 and 1958, it managed to oust the Spanish and take control of a large part of Western Sahara. An interesting detail is that units of the Algerian FLN took part in these military operations aimed at reunification with Morocco.36

Carried away by its momentum (and perhaps intoxicated by its success), the Liberation Army made the mistake of attacking Mauritania, then a French colony. Paris had its powerful army in Algeria and decided to respond. This resulted in Operation Écouvillon, a successful temporary alliance with Madrid. The Moroccan regular army, meanwhile, remained neutral on the orders of the Sultan.

The attempt did at least result in the return of the Tarfaya strip further north, with Spain showing sensitivity to Mohammed V’s elegance of attitude. After his death in February 1961, the issue was dominated by the caution of the young King Hassan II, who was grappling with internal dissent and legal uncertainties abroad. Compared to the national movement, made up of militants inclined to take risks, he was more cautious: his throne and his dynasty were at stake.

Meanwhile, the ‘Sand War’ (1963) dashed any hopes of rectification with Algeria. At the same time, claiming Mauritania proved unrealistic for several reasons: the Spanish Sahara formed a barrier between that country and Morocco; the stubbornness of Mauritania’s first president, Ould Dada, who was committed to an independent state; and France’s support for this project. It was not until 1969 that Morocco officially renounced its claim. However, it did not wait until then to realise that Western Sahara was its only remaining option for redressing the territorial injustices of which it considered itself a victim.

In 1963, Hassan II decided to refer the matter to the UN on the basis of Resolution 1514, requesting that Western Sahara (and the Spanish enclave of Ifni) be included on the list of Non‑Self‑Governing Territories, where it still appears today. This referral gave the UN a hand, something that other countries facing territorial disputes have refrained from doing.37 Some Moroccans now wonder whether this decision was wise. Nevertheless, it led to a second recovery of territory: the city of Ifni in 1969. Such are the constraints of ‘independence in stages’: it requires compromises that can be used against you later. Intransigeance does not have this disadvantage.

In the Sahara, General Franco put up resistance. For Spain, its occupation was a means of securing the Canary Islands, which it owned just opposite. More seriously (for Morocco), Madrid cherished the hope of independence for the territory, separate from Morocco, in favour of a state that it would keep under its influence. Relations with Algeria went through ups and downs: Algerian statements in favour of the Moroccan cause in Western Sahara, but also pressure from that country on Spain to organise a referendum before its departure (to which Franco seems to have committed himself).

All this fuelled local unrest. In the early 1970s, a Sahrawi student in Rabat, a certain El Ouali, asked the Moroccan nationalist parties for weapons to ‘liberate’ Western Sahara (reunite it with Morocco). He was rebuffed by his interlocutors, who now considered this a matter for the state. Morocco had just experienced its first bloody coup d’état (Skhirat, 1970). El Ouali was unable to gain access to official contacts. In 1972, he organised a demonstration in Tan-Tan, a Moroccan town close to the Spanish demarcation line. It was repressed by General Oufkir, still Minister of the Interior, and that was when history took a turn.38

The Sahrawis

The leader, who saw himself as Moroccan but whom Rabat had just alienated, belonged to one of the most warlike tribal groups in the entire Sahara, the Reguibets. Many French writers have written about these valiant nomads.39 Among them is Le Clézio, who is married to a Sahrawi woman and is a Nobel Prize winner for literature.

This group nomadises in a vast area including eastern Western Sahara, southern Morocco within its 1956 borders, Algeria, Mauritania and Mali, often at a relative distance from the sea. These are camel tribes (better equipped for combat than tribes whose herds consist mainly of goats and sheep). They travel and raid, moving closer to the coast when the rains bring up temporary pastures for their animals. This group of tribes is believed to have frequently dominated other tribal groups in the region. It was to become the spearhead of the Polisario Front.

In the north-west of Western Sahara, closer to the sea, there is another group of tribes, the Teknas, often described as more peaceful, living and nomadising on both sides of the former Spanish-Moroccan demarcation line in the Sahara. Further south, but also near the sea, is a third group: the Ouled Delim.

The conflict plunged these three tribal groups into a tragedy: the brutal sedentarisation of people who had been living a nomadic lifestyle. This is a way of life: people live in tune with the elements, following the animals as much as they are followed. It is an imaginary world: ancestors, oral culture, the next departure. The group is everything, with its songs and its leaders. Private property does not exist.

All this was interrupted by the guerrilla war between the Polisario Front and the Royal Armed Forces. The former drove part of the population into camps, those of Tindouf in Algeria. The Moroccan authorities gathered another part in the cities under their control.

This brutal sedentarisation is an undeniable tragedy. It is rarely mentioned. This very real human tragedy is overshadowed, in the minds of some of the international community, by the more abstract tragedy of the absence of an independent state. This state would have united the different tribal groups that crossed paths in this vast space. But did these groups really come together and merge into one nation?

A French anthropologist sympathetic to the Polisario Front recounted the beginnings of this organisation in a book poetically entitled La République des Sables40 (The Republic of Sands). Reading it, we discover the appeal of the UN resolution on self‑determination. An assembly of tribes was convened. According to her account, the participants were presented with the prospects that would open up to them if they renounced their tribal identity and proclaimed themselves a people: a state, a seat at the UN, wealth. They were invited to forget their origins (especially their tribal affiliations) overnight in order to qualify for self‑determination.

It is up to each of us to reflect on this episode. It can be seen either as a leap into political modernity legitimising a State, or as an artificial act masking the tribal reality. Historians who have studied nations around the world have generally described their formation as a process rather than a sudden rupture.41

The convergence of histories

Shortly after its creation, the Polisario Front obtained external support, first from the distant and turbulent Libya of Muammar Gaddafi, then from Algeria. This is where the two histories, that of relations between the Maghreb’s major powers and that of the conflict, converge. Algeria, as we have seen, did not create the conflict out of thin air; it would be a mistake to believe so. But its support for the Polisario was massive, to the point of becoming decisive.

The Polisario Front became dependent on it, particularly financially. Algeria gained considerable influence over the Front. This allows us to view the conflict as a Moroccan-Algerian affair, dependent on relations between the two countries. Algiers sometimes rejects this interpretation but insists on its role as a ‘third party interested in the conflict’ and makes its ‘resolution’ a prerequisite for rapprochement between the two countries.

In addition to this conflict between neighbouring countries, Morocco faced internal quarrels. After the accession of Hassan II, some members of the Moroccan Left settled in Algiers. During the ‘Sand War’, some of them did not hesitate to take the side of Algeria, which was haloed with a revolutionary image. The case of Ben Barka, a Moroccan opposition figure who was kidnapped in Paris and then tortured to death by Oufkir and his henchmen in October 1965, further fuelled the hatred. It seems that members of the Moroccan ‘left’ introduced the Polisario to the Libyans, then to the Algerians, to weaken Hassan II.

Internal dissensions within Morocco therefore had a major role in triggering the conflict. It is a little-known factor: no country likes to talk about its internal tensions. However, by glossing over this aspect, the Moroccan narrative deprives itself of a perspective that is rather favourable to its arguments. It gives the conflict a national, ideological cause. This does not point to an ‘international’ affair, pitting ‘Moroccans’ against ‘Sahrawis’, but rather to an internal conflict exploited from outside.

Hassan II’s ‘Pont d’Arcole’

In the early 1970s, the Western Sahara issue began to take a worrying turn for Rabat. The international community showed indifference to the peaceful methods favoured by Morocco until then. The Vietnam War ended with the complete victory of the North and the South Vietnamese NLF in 1975. After the political success of the Algerian FLN against France, this military success against the United States and its allies marked a triumph for the liberation fronts against the Western powers. And in the West, part of public opinion viewed these armed movements with admiration.

Morocco’s peaceful options were viewed with disdain by this faction of public opinion, as if they confirmed the archaism of the regime. This was a serious misjudgement. However, Spain and France could not completely succumb to it. Deep down, they knew what they owed to these options: the irreplaceable value of lives saved and the inestimable value of friendships preserved.

This was Morocco’s hope of recourse in the face of the wall of incomprehension it was about to encounter. Contrary to popular belief, France and Spain did not listen to Morocco simply out of friendship. Foreign policy does not obey feelings. But, when a friend is the victim of an injustice, your sense of honor is affected.

Hassan II cultivated the friendship of Morocco’s two former colonial powers with high dedication. With Spain, the game was long hampered by that country’s local calculations against Morocco and the Polisario’s links with part of Spanish civil society.

With France, initially, it was worse: the king had his share of the difficulties. The Ben Barka affair was a murder, an affront to French sovereignty, and this political scandal broke out in the middle of the presidential campaign, in October 1965. Outraged to the highest degree, General de Gaulle recalled the French Ambassador to Morocco and interrupted all contact at his level with the King, which he did not restore during his presidency.42

The Ben Barka affair had effects comparable to those of the Sultan’s deposition, but in reverse. After its huge blunder in 1953, France had strived to repair its relations with the Moroccan monarchy. Similarly, Hassan II did a great deal between 1965 and 1975 to restore harmony with the French authorities. The role of crises is a strange feature of the relationship between the two countries. It is true that the official break had not erased the exceptional closeness of human relations between the two countries.

As 1975, the year of the Green March, approached, Franco-Moroccan friendship was at its zenith. Fortunately for Morocco, it was not its only Western friendship, but it was the strongest. The horizon was clouded. After two attempted coups (in 1970 and 1972), the domestic democratic opposition refused to negotiate with Hassan II. Spain and Algeria, each with their own dreams but believing they had the same interests, envisaged an independent Western Sahara close to them. A formidable group of tribes took the path of the Siba, the rebellion against the Sultan that punctuated the history of Morocco.

As for the international authorities, they revelled in themselves after discovering the philosopher’s stone of self‑determination. There was no question of the Third World high mass being disrupted by Moroccan peculiarities. Many conditions are therefore in place to forge an independent state in Western Sahara, condemning Morocco to a permanent stunted territory.

The use of force remained an option, in this case against Spain, the occupying power in Western Sahara. But this had three drawbacks for Morocco. The first was that it would lose some of the moral credit for its pacifist choices. But, after all, since it was hardly credited with any… The second was more troublesome: it would deal a serious blow to Spanish friendship. But with colonial power, difficult to avoid, decolonisation was a necessity. The third drawback was even more formidable: the prerogatives of the UN and the Security Council in matters of peacekeeping and peacemaking. These allowed the latter to mandate a military force to evacuate the Royal Armed Forces.

Divided, misunderstood, cut off from Africa, targeted by supporters of the international revolution, could Morocco afford such a luxury? Perhaps it could play on its friendships, but how far could it push its luck? The distant United States indicated its opposition to unilateral action by Morocco in an official letter addressed to the king in September 1975 by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

The French rope proved to be stronger. However, Paris could not ruin its credibility by appearing to be a pirate of international law. Morocco possesses that Mediterranean virtue of not putting its allies in a difficult position. It would incorporate French constraints into its reasoning.

For the rest, the king found himself, politically and legally, in a situation that could be compared to that of Napoleon at Arcole: having to cross a narrow bridge, with enemy weapons trained on him.

The scope of the Green March

Statement by Yahia Zoubir. 25,000 Moroccan soldiers had entered the territory at the end of October.

Daniel Calleja-Crespo, Director of the European Commission’s Legal Service, experienced the events as a Spanish student. This brief account owes much to him.

Interview with the author.

As at Arcole, three conditions had to be met in order to proceed: calculate the risks, accept a certain level of damage and, once the decision had been made, go ahead, whatever the cost.

Given the close bilateral relations, the reflections brought together the Moroccans and the French. Alexandre de Marenches, the romantic and eloquent head of French intelligence, boasted that he had come up with the idea for the ‘Green March’. Let us refrain from such conjecture. After a brainstorming session, everyone believes they were the first to come up with the idea. If the March had been a fiasco, no one would have disputed the king’s authorship. He was indeed the mastermind, even if he knew how to consult others.

The extraordinary spectacle of an unarmed and determined crowd is the flagship event of Morocco’s assertion of sovereignty in the Sahara. How can one be insensitive to such a symbol? Nevertheless, let us make an effort to keep a cool head and listen to Algerian criticism. The Green March was not ‘so green’ after all. In fact, the royal armed forces had entered the territory.43 Legally, this remains a unilateral action. On this point, it is impossible to dismiss the Algerian point of view. In other words, the damage accepted was Morocco’s image in the eyes of the law and the exploitation that would result from it. It was at this precise moment that the legal loophole opened, which has not been closed.

But for the King, it was an inevitable evil. He did not believe it was realistic to imagine that, by remaining well-behaved, Morocco would then see the international community descend from Olympus to grant it sovereignty over Western Sahara. The history of international relations teaches us otherwise.

Likely, this reasoning did not suit Paris, given the diplomatic adventure that lay ahead. Yet it was accepted, more out of intimacy than friendship: it was impossible to tell the Moroccans they were wrong when, deep down, the French agreed with them. An alliance was sealed. It was based on a strong but politically incorrect conviction, binding the two countries but difficult to proclaim publicly.

As for the Green March, the symbol it represents is not negated by the army’s role in taking control of the territory. To those who describe Morocco as an aggressor, the March provides a retort: are there so many aggressors who oppose guns with their unarmed chests? Can we imagine Saddam Hussein’s Iraq or Vladimir Putin’s Russia carrying out such a gesture in Kuwait or Ukraine?

The method is a call for justice whose sincerity is difficult to dispute. The nobility of the physical risks taken filled Moroccans with pride. It obviously helped France to lend its support, weathering criticism but controlling the risks.

On 6th November 1975, the crowd gathered in Tarfaya at the end of a road built by the Bouygues group began to move. Morocco had created an element of surprise. Few thought it would dare. To avoid suspicion, the enormous logistical requirements were partly covered by orders placed through a company based in Savoie. This surprise effect had a downside: it made it impossible to prepare international opinion. But it was worth the risk. Madrid did not dare to fire. That was Hassan II’s gamble.

Francisco Franco was in a coma, Juan Carlos was taking his first steps as interim head of state, and the Spanish people’s hearts were filled with hopes for democracy. Tarnishing the moment with bloodshed would have spoiled it. Under shock, Madrid agreed to negotiate. The king knew how to calculate.44

The negotiations led to the Madrid Accords of 14th November 1975. They provided for the division of Western Sahara between Morocco and Mauritania (approximately two-thirds to one-third: the northern part known as Saqia El Hamra for the former, the southern part known as Rio de Oro for the latter). For Rabat, this was an act of decolonisation and a legal basis for its sovereignty. For others, a colonial power could not dispose of its former possession and the Spanish signature was worthless.

In reality, Moroccan sovereignty was to be exercised, initially over two-thirds of the territory. In 1979, Mauritania, eager to end the conflict, withdrew from Rio de Oro. It recognised the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), no doubt to avoid trouble with the Polisario Front and Algeria. However, as the latter was far from the area in question, Morocco settled there without difficulty. Its de facto sovereignty then extended to most of Western Sahara.

Domestic political manoeuvre or historic compromise?

The domestic repercussions of the Green March, like other aspects of the conflict, have been cited more than studied. Let us begin with an obvious fact, confirmed by all visitors: the deep, visceral support of the Moroccan people. It is not unreasonable to conclude that national unity around the king was a central objective. From this fairly accurate premise, some deduce that the king acted to increase his power by paralysing the opposition. The premise is plausible, but the conclusion is false.

History will remember that the Green March was part of a process of consolidating the monarchy. But this came at the cost of a historic compromise and a gradual limitation of his powers.

The domestic situation was as follows: the national movement, historically the champion of the territorial cause, demanded a reduction in royal prerogatives. It had only paid lip service to condemning the assassination attempts (1971, 1972). The Istiqlal, the National Union of Popular Forces and the PPS (former Communist Party) had allied to push through constitutional reform. This was the ‘Kutla’, an agreement that revived the unity of the national movement. These parties boycotted the elections, which were revealed to be rigged.

Ali Bouabid, Director of the Bouabid Foundation and son of Abderrahim Bouabid, leader of the UNFP and then of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP), interprets the sequence as follows: ‘With the Green March, the king touched the patriotic nerve of the national movement. In doing so, he forced them to return to negotiations with him.’45 Over time, these negotiations led to democratic openness, a form of historic compromise in the Moroccan style.

This point in domestic history is important. Internationally, the Green March has sometimes been described as an instrument of despotism. This interpretation, encouraged by certain Moroccan exiles, has been hammered home by the Polisario. It has influenced opinion but is inaccurate: on the contrary, a plausible link can be established between the March and democratic openness. It should be noted here that, after the intellectual bias caused by intangibility, a second misunderstanding distorted the analysis. In our view, the biases that influenced international resolutions are sufficient to justify a critical approach to them.