Poland's security in the 21st century: challenges, strategies and prospects

Introduction

Historical and geopolitical context

Security – the national dimension

Legal aspects

The foundations of national security

Changes to the defence budget

Plans to acquire military equipment

Development of the armed forces

Russia’s hybrid war

The ‘Eastern Shield’ (Tarcza Wschód)

Regional cooperation, a pillar of Poland’s security

Poland’s role in the European security system

The transatlantic dimension of Poland’s security

Poland in NATO

Cooperation between Poland and the United States

The war in Ukraine: a game changer for polish security

Conclusion

Summary

This paper analyses the evolution of Poland’s geopolitical position and its role in shaping the security architecture of Central and Eastern Europe and transatlantic structures. In response to the upheaval in the international order, Poland has developed its defence capabilities and played an active part in the security policy of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and the European Union (EU). Tensions in transatlantic relations, the Russian-Ukrainian war, increased rivalry between world powers and the EU’s aspirations for strategic autonomy are key factors influencing contemporary strategic challenges. Faced with these challenges and in response to growing threats, Poland is investing to expand its armed forces, thus aiming to create the largest land army in Europe, and is implementing a national defence modernisation programme, notably with the ‘Eastern Shield’ project.

Poland has reinforced its influence on international security issues by increasing its defence spending, rising to 4.7% of GDP by 2025, and intensifying cooperation with European partners. The political context, including the 2025 presidential elections in Poland and the Polish Presidency of the EU Council in the first half of 2025, will also influence the future direction of its security policy development. Poland is facing a new multipolar world, where it is necessary to combine cooperation between allies and the development of its own defence capabilities. According to Zbigniew Brzeziński’s historic diagnosis, Poland’s future depends on strategic partnership with NATO and the United States, European cooperation, and the strengthening of regional security mechanisms. Today, we can doubtlessly say that Warsaw has become the capital of European security in 2025.

Kinga Torbicka,

Lecturer in the Department of Strategic Studies and International Security at the Faculty of Political Science and International Studies, University of Warsaw.

Polish, American and British soldiers take part on 21 September 2022,

in Nowa Dęba, eastern Poland, in the joint military exercise BEAR 22.

The operation, which involved Polish Leopard tanks and American Abrams,

was aimed at strengthening interoperability and cooperation between the Allies.

As a result of the current paradigm shift and the consequent reconstruction of the international order, Poland is taking massive action to ensure its national and international security. The international situation has become unstable for both Poland, Europe and the world due to challenging relations with the US, worsened by the return of Donald Trump to the White House, the Russian-Ukrainian war, the return to superpower rivalry (United States, Russia, China), technological advances, the consequences of the German elections, the hybrid war waged by Russia against the West and the need for a common defence for the European Union. The Polish Presidency of the Council of the European Union (1st January – 30 June 2025), the presidential elections in Poland (18 May 2025), the significant increase in national defence spending (4.7% in 2025), the plans to create the largest army in Europe (around 300,000 soldiers in 2035) and the ‘Eastern Shield’ project confirm this international tension. Faced with a ‘new Cold War’, Warsaw is becoming the capital of European security.

Historical and geopolitical context

Stanisław Zarobny, «Przemiany w polskiej kulturze strategicznej w kontekście wyzwań i zagrożeń XXI wieku”, Studia nad Bezpieczeństwem, nr 4, 2019, pp. 63-78 [online].

The expression «Yalta betrayal» appears in the work of researchers on Polish history. It is synonymous with the abandonment of Poland by its Western allies, also known as the «Fourth Partition of Poland».

Stanisław Zarobny, op. cit.

Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, Free Press, 1992.

Kinga Torbicka, «How to continue solidarity? A conversation with Lech Wałęsa», Le Grand Continent, 10 April 2019 [online].

«All these show that Poland is firmly committed to NATO and that NATO is firmly committed to Poland’s security. This is important as we continue to adapt to the most unpredictable security environment we have seen in a generation.» «For NATO Secretary General, Poland makes major contributions to our common security», NATO, 4 June 2019 [online].

Stanisław Koziej, «Nowa zimna wojna na wschodniej flance», Pulaski Policy Papers, nr. 3, 2 April 2019 [online].

Edward Lucas, The New Cold War. Putin’s Threat to Russia and the West, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2014.

Poland’s security strategy has been built on the following three elements: historical experience, geopolitical conditions and external factors that determine the country’s position in international relations. According to Stanisław Zarobny, these three variables have shaped Polish awareness of security and its defence system.1

Historical events have had a particular impact on the definition of Poland’s security policy. The partition between Prussia, Russia and Austria-Hungary shaped a Polish identity conscious of external threats, while the struggle to regain independence throughout the 19th century, and its brief restoration in 1918, reinforced the need to build a strong State capable of defending its sovereignty. The Second World War, followed by the ‘Yalta betrayal’2 and Poland’s subordination to the Soviet Union (USSR), confirmed the importance of alliances and their influence on national security. The communist period (1945-1989) was a period of limited sovereignty, during which Poland was not a player in international relations but a spectator, since it could only have a very limited influence. As a member of the Warsaw Pact and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA), which brought together the countries of the Communist bloc, Poland was entirely subordinate to the Soviet Union. Its dependence on foreign powers and its transition after 1989 influenced Poland’s strategic culture, emphasising a strong defence and the need for integration with the West to guarantee its security. Stanisław Zarobny calls these determinants ‘dispositions’ and defines them as ‘deep and enduring patterns of interpretation, which shape the interpretation of the nation’s fundamental interests and explain the differentiation of Polish strategic culture.’3 Its position between two powerful neighbours, Germany and Russia, determines its security strategy. These two States have historically been seen as threats. After German reunification (1990) and the collapse of the USSR (1991), Poland took the strategic decision to join the Euro-Atlantic institutions by joining NATO (1999) and then the EU (2004), a key element in the construction of the security policy of the Third Republic of Poland.

Poland’s current geopolitical situation is the result of changes in the post-1989 international system. For the purpose of this analysis, we have divided it into two periods : 1989-2014 and 2014-2025.

The first period was characterised by geopolitical changes that had a significant impact on Poland’s security: the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the USSR and the redefinition of political and military blocs. The ‘end of history’ predicted by Francis Fukuyama4 marks the beginning of a new chapter in Poland’s history5: the conquest of its sovereignty and its ability to take decisions, particularly in the field of foreign and security policy. Poland left the Warsaw Pact in 1991 – the last Soviet soldiers left Polish territory in 1993 – and regained full sovereignty. It then concentrated on integrating into Western political and security institutions. Membership of NATO and the EU were the foundations of Poland’s security policy, strengthening its position within the Euro-Atlantic community.

The present period brings new threats to Poland’s security, leading to a redefinition of its security strategy. This period began with the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014: a shock for the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Since the Crimean war, the relations have deterriorated between the West and Russia, which de facto forced Poland to adapt its security strategy. In 2019, Jens Stoltenberg, then Secretary General of NATO, described this situation as ‘unpredictable security’6, highlighting the growing number of threats and their multidimensional nature. As a key member of the transatlantic alliance, Poland found itself at the centre of the rivalry between Russia and the West, which Polish General Stanisław Koziej described as a ‘neo-Cold War confrontation’.7 This confrontation takes the form of a hybrid war led by Russia, combining military, cyber, economic and disinformation activities. As a NATO and EU border Sstate, Poland has been faced with an urgent need to increase defence spending and strengthen the Alliance’s eastern flank. As part of this ‘new Cold War’8, Poland found itself at the epicentre of a strategic rivalry aimed not only at building a defence against a direct military threat, but also at protecting the integrity of Euro-Atlantic institutions. By renewing its imperial ambitions, illustrated by the annexation of Crimea, Russia sought to destabilise Western security structures through asymmetric actions.

The escalation of Russian military aggression in 2022 was, in Poland’s eyes, a confirmation of the resurgence of Vladimir Putin’s aspirations to revive ‘Greater Russia’, i.e. the imperialist vision of a Russia that would dominate the countries of the former USSR. Today, this concept is associated with a desire to rebuild Russia’s influence and its status as a great power, often at the cost of other countries’ sovereignty. Vladimir Putin’s actions, in particular the attack on Ukraine, are the embodiment of this idea.

Poland shapes its security policy according to geopolitical dynamics and historical experience. Its difficult position between Germany and Russia leads it to focus strategically on defence and international alliances. Poland’s history – the partitions, the Second World War, the communist period and the post-1989 transition – has shaped the country’s strategic culture. Membership of NATO and the EU has strengthened Poland’s position in Euro-Atlantic structures, providing it with greater stability and security. After 2014, faced with aggressive Russian policies, Poland increased its defence spending and became a more active supporter of strengthening NATO’s eastern flank.

Security – the national dimension

Legal aspects

Ustawa z dnia 21 listopada 1967 r. o powszechnym obowiązku obrony RP, Dziennik Ustaw 1967 nr 44 poz. 220, ISAP [online].

Stanisław Koziej, Adam Brzozowski, Strategie bezpieczeństwa narodowego RP 1990–2014. Refleksja na ćwierćwiecze, [w:] Robert Kupiecki (red.), Strategia bezpieczeństwa narodowego Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Pierwsze 25 lat, Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita, Warszawa 2015.

Ibid.

Article 5 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland states that: ‘The Republic of Poland shall safeguard the independence and inviolability of its territory, ensure the freedoms and rights of man and citizen and the security of citizens, protect the national heritage and ensure the protection of the environment, guided by the principle of sustainable development’.9 The Act of 21 November 1967 defines the universal duty to defend the Republic of Poland10 and gives this principle its legal basis. It regulates the principles of organisation and operation of the State’s defence system, as well as the powers of the public authorities in this regard. In accordance with Article 4a of the Act, the President of the Republic of Poland protects the sovereignty and security of the State, as well as the inviolability and indivisibility of its territory. At the request of the Prime Minister, it approves the national security strategy. Finally, the Act defines the threats to the State and the direction of current action in the field of defence policy and national security: ‘one of the most important and urgent challenges for Poland after 1989 was the formulation of a national strategy and the development of an independent security policy tailored to this strategy, including a defence policy’11.

General Stanisław Koziej suggests dividing the strategies into those that were put in place just after 1989, in the conditions when Poland was regaining its ‘strategic independence’ and negotiating NATO membership, and those that came later when Poland was already a member of the Alliance after 1999.12

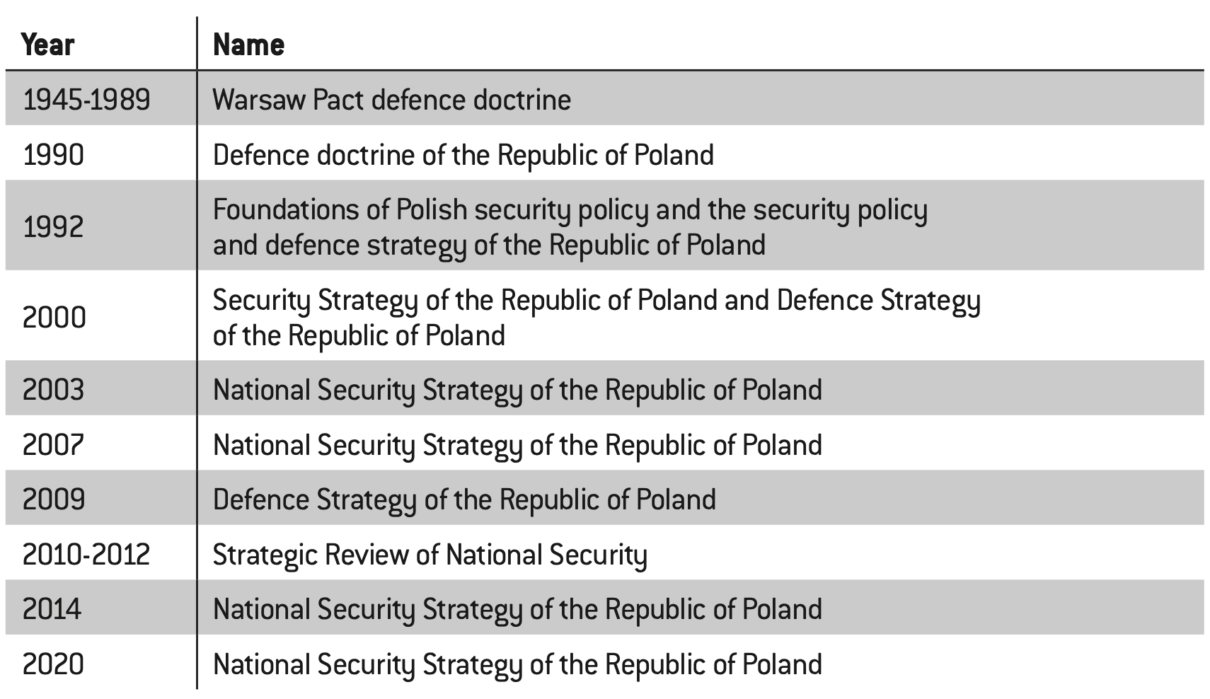

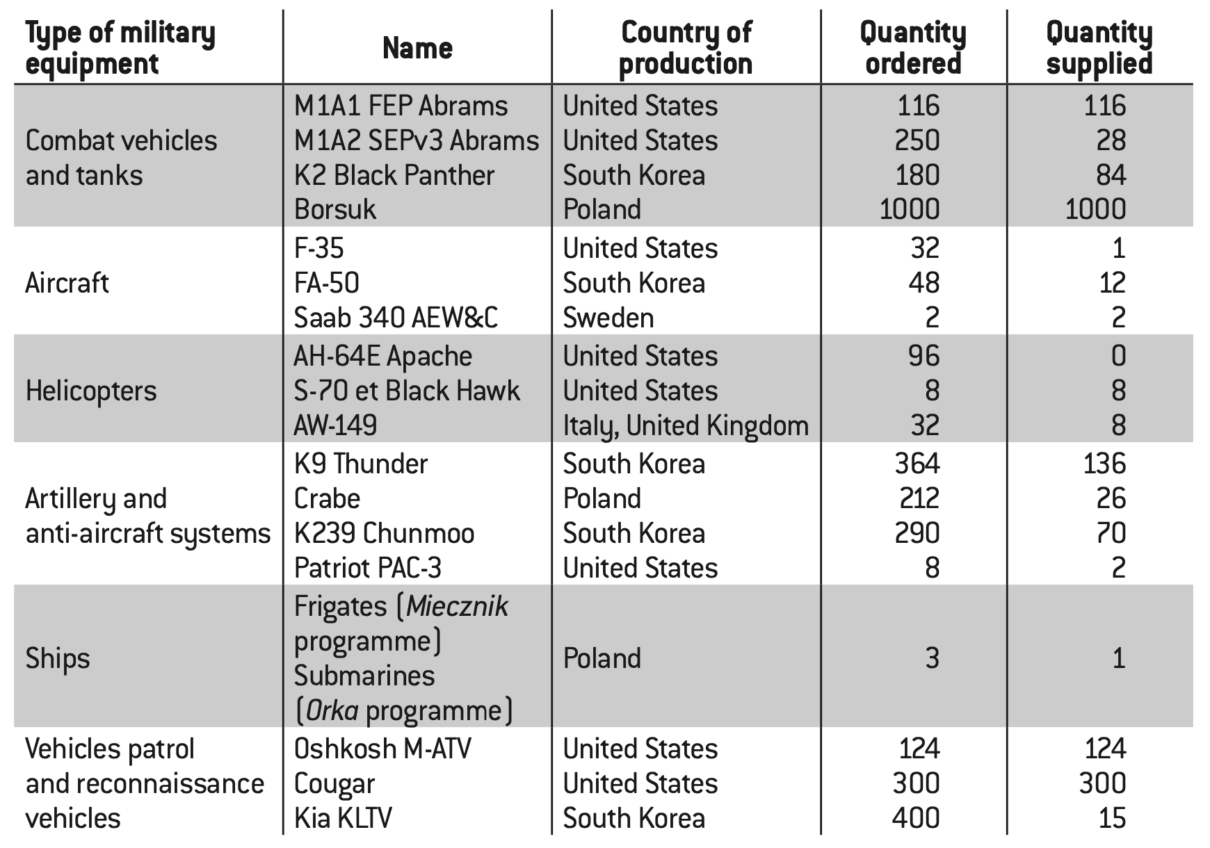

Table 1: Main acts regulating defence policy (1990-2020)

Source :

author’s study

The foundations of national security

Strategia Bezpieczeństwa Narodowego Rzeczypospolitej Polski, 2020

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Andrzej Duda, Rekomendacje do Strategii Bezpieczeństwa Narodowego Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, Office of National Security, 4 July 2024 [online].

Rekomendacje do Strategii Bezpieczeństwa Narodowego Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, op.cit.

The National Security Bureau (BBN) is the Polish office that carries out national security tasks assigned to it by the President of the Republic of Poland. It assists and supports the President in the implementation of his tasks in the field of security and defence. It was created in 1991 by Lech Wałesa [online].

Poland is currently basing its national security strategy on a solid alliance with NATO and the EU13, as the Act of 2020 emphasises: ‘the fundamental factor shaping Poland’s security is its strong anchorage in transatlantic and European structures, as well as the development of bilateral and regional cooperation with the most important partners’.14 Moreover, the ‘strategic partnership with the United States of America’ in the field of security and defence is considered a priority.15

The first element of the act is an analysis of the security environment, which takes into account the internal and international factors affecting Poland’s strategic situation. The current threats to Poland’s security are linked to Russia: ‘the most imminent threat is the neo-imperialist policy of the authorities of the Russian Federation, implemented by military force’.16 Another category of threat is the continuation of regional conflicts on the southern periphery of Europe. The document also details other risks to the country’s security (China/United States rivalry; hybrid operations; energy security, health challenges, etc.).

It then sets out the national values, interests and objectives that form the basis of the State’s defence and security policy. National security is based on the implementation of specific strategic interests, which are reflected in four pillars of security policy: the security of the State and its citizens, Poland’s role in the international security system, national identity and heritage, and social and economic development and environmental protection.

The first pillar entails integrating the national security management system and strengthening the country’s defence capabilities. In this area, resilience to threats, the development of the armed forces, technological modernisation and the strengthening of cyber security are of paramount importance. It is equally important to guarantee information security, including the fight against fake news and hybrid threats.

The second pillar sets the cooperation within NATO and the EU as a priority, thus contributing to improve the defence capabilities of the country and of the Euro-Atlantic region as a whole. The development of bilateral and regional cooperation is an important element through which Poland can contribute to shaping security policy in Europe and the world.

The third pillar emphasises on the importance of historical values, the Christian heritage and universal principles that shape the country’s social cohesion.

The fourth pillar encompasses social and economic development and environmental protection. It stipulates that security is not limited to military issues, but includes tackling social exclusion, climate challenges and supporting growth. Attention to the citizen’s quality of life of citizens and the environment strengthens the State’s resilience to both internal and external crises.

Implementing Poland’s security strategy requires the involvement of government institutions, local administrations and other entities responsible for specific aspects of security. It operates within the framework of existing legislation, and is regularly reviewed for verifications and adjustments to ensure the highest level of national security. In the future, detailed mechanisms for implementing the strategy should be set out in the new National Security Management Act.17

This strategy was drawn up after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and before the outbreak of the large-scale war in Ukraine. It should be adapted to current geopolitical conditions and to take Poland’s new security situation into account. Work is underway to draft a new act. In July 2024, the outgoing President of the Republic of Poland, Andrzej Duda, submitted his recommendations to the Government for the new National Security Strategy of the Republic of Poland.18 These strategies were prepared by the National Security Bureau,19 after consultation with 60 experts.

Changes to the defence budget

PLN is the acronym for the Polish national currency the złoty, whose value is 4 złotys to 1 euro (4.271 as of 17 June 2025).

The Armed Forces Support Fund (FWSZ) was created on 23 April 2022 under the Internal Defence Act (UO). It is one of the three main sources of funding for the Polish army, along with the Sstate budget and funds from the sale of shares in defence companies. The National Economy Bank (BGK) is responsible for setting up and managing the Fund under an agreement with the Minister of Defence. The Fund finances the tasks defined in the «Armed Forces Development Programme» (FWSZ), as well as the detailed modernisation, acquisition and investment plans of the Polish Armed Forces. The FWSZ replaced the Armed Forces Modernisation Fund (FMSZ), which had less financial capacity and could not grant loans. FWSZ’s income comes mainly from loans, bonds and budget funds. The FWSZ cooperates with the Ministry of National Defence, the BGK and the Ministry of Finance. «Art. 41. Utworzenie Funduszu Wsparcia Sił Zbrojnych», in Ustawa z dnia 11 marca 2022 r. o obronie Ojczyzny, Wolters Kluwer, 19 March 2025 [online].

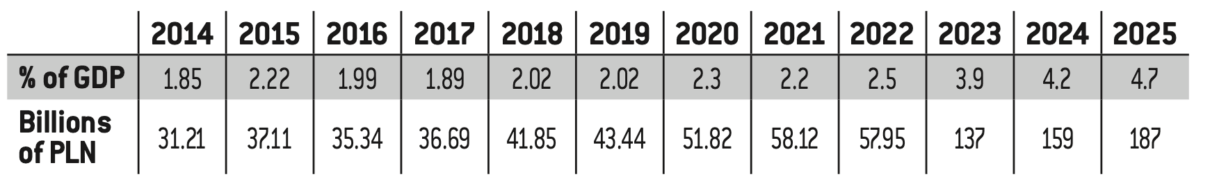

The legal framework for security and defence policy described above has had an impact on Poland’s activities to ensure the country’s stability and security. Poland has been increasing its defence spending for many years. According to a report by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, Poland will have moved up from 20tht to 15th in the world in terms of defence spending by 2024.20

In 2013, this expenditure represented 1.72% of GDP (PLN21 28 billion), while in 2025 it will reach 4.7% of GDP (PLN 186.6 billion). In 2025, the defence budget will have increased by PLN 28.6 billion or 18.1%: a direct consequence of the Russian war in Ukraine. Total defence spending amounts to PLN 124.3 billion from the Sstate budget (3.1% of GDP), of which PLN 14 billion is paid into the Armed Forces Support Fund (FWSZ).22 A further PLN 76.3 billion comes from the FWSZ. Around 41.7% of defence spending will be allocated to investment and the purchase of military equipment. The increase in spending in 2025 will be financed, among other things, by loans and bond issues from the Armed Forces Support Fund (FWSZ), whose debt will amount to PLN 113.1 billion by the end of 2025. Although the planned expenditure will strengthen Poland’s position within NATO, it represents a considerable budgetary burden. With a budget deficit expected to reach PLN 289 billion (7.3% of GDP), there are concerns about the financial sustainability of the plan, given that the burden of the increase in defence spending rests entirely on the Armed Forces Support Fund (FWSZ).

Table 2: Polish defence spending

Source :

‘Military expenditure by country, in millions of US$ at current prices and exchange rates, 1949-2023, Military expenditure by country as percentage of gross domestic product, 1949-2023’, SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, 2023 [online] ; Ustawa budżetowa na 2021 rok, 20 January 2021 [online] ; „Odpowiedzialny, ale hojny – budżet na 2025 rok przyjęty”, Chancellery of the President of the Council of Ministers, 28 August 2024 [online] ; Decyzja budżetowa na rok 2025 nr 10/Minister obrony narodowej z dnia 23 stycznia 2025 r., Dziennik urzędowy Ministra obrony narodowej, 24 January 2025 [online].

Table 3: Poland’s defence spending compared with that of the Visegrád countries (2022-2024)

Source :

author’s study

Plans to acquire military equipment

Poland is also negotiating the installation of the HIMARS rocket artillery system. The contract with the USnited States was signed before the outbreak of war in Ukraine and Poland currently has twenty sets of this type. The PiS government (2015-2023) signed a framework agreement to deliver up to 500 units, but negotiations are still ongoing in 2025.

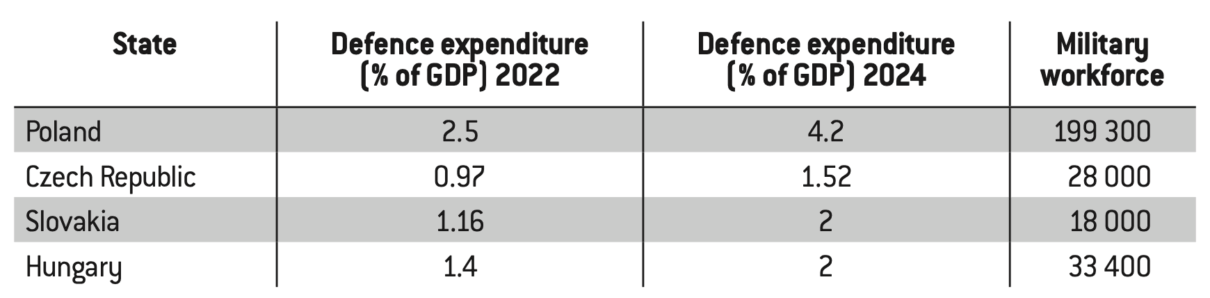

The increase in spending is accompanied by a plan to acquire military equipment, mainly from the United States and South Korea. In addition, Poland has obtained a $4 billion loan from the United States to purchase other military equipment, including Patriot air defence systems and Apache helicopters. Poland’s armed forces have been under-funded for decades, with obsolete equipment dating back to the Warsaw Pact era. Until Poland joined NATO in 1999, there were few purchases and limited opportunities to modernise the Polish army. The situation changed radically in February 2022, when a significant number of Polish weapons were sent to the Ukrainian front, prompting the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to sign new contracts.23 The orders placed, some of which were delivered in 2025, concern various types of military equipment. The most important of these are:24

– Combat vehicles and tanks: Poland will have a total of 128 Leopard 2 vehicles (Germany) and has ordered M1A1 FEP Abrams (USA) after 2022, of which 116 have already been delivered. Deliveries of the more advanced M1A2 SEPv3 Abrams and K2 Black Panther (South Korea) are also underway. In addition to tanks, the Polish army should also have 1,000 Borsuk (Poland) infantry fighting vehicles, making it a major armoured force in Europe;

– Aircraft: the Polish army currently has 48 F-16 fighter jets (USA) in stock. To modernise the air fleet, modern F-35 fighters (USA) have been purchased, with deliveries scheduled for 2026. FA-50 aircraft (South Korea) have also been ordered. Two Saab 340 AEW&C aircraft (Sweden) have also been purchased for early warning and airspace control;

– Helicopters: AH-64E Apache aircraft (USA) are currently being acquired. The first deliveries are scheduled for 2028, but until then the machines will be leased by the US Army. Deliveries of AW-149 multi-purpose helicopters are also under way (Italy, United Kingdom);

– Artillery and anti-aircraft systems: one of the Polish army’s main contracts concerns the acquisition of K9 Thunder systems (South Korea). In 2025, Poland received more than 130 howitzers out of more than the 360 machines ordered, while the framework contracts provided for nearly 700 units. The Polish army has Krab domestic howitzers, but the exact number is difficult to determine as some have been transferred to Ukraine. It is estimated that there are around twenty in Poland, although the aim is to acquire more than 200. Poland is still awaiting delivery of eight Patriot system batteries (USA), although the ambition is to have many more;25

– Ships: the navy is an essential component of the Polish army. After years of underfunding, two priority programmes are being implemented to modernise it. The Miecznik (Swordfish) programme, which involves the construction of three frigates (the first of which is due to enter service in 2029), and the Orka (Orca) programme. Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz, Minister of National Defence, announced that under the latter programme, the navy should receive new submarines.26 In the competition for the contract for new submarines for Poland, bids were submitted by France (Naval Group), Sweden (Saab), Italy (Fincantieri) and South Korea (HHI Group).

– Patrol and reconnaissance vehicles: the Polish army currently has 124 Oshkosh M-ATVs and Cougars (USA) in stock. An order for Kia KLTV light vehicles (South Korea) is in progress.

Table 4: Summary of military equipment purchases

(delivered and planned, as of January 2025).

Source :

compilation propre fondée sur les données du ministère de la Défense et de l’Agence de l’armement.

Development of the armed forces

Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2 April 1997, op. cit.

„Ustawa z dnia 17 grudnia 1998 r. o zasadach użycia lub pobytu Sił Zbrojnych Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej poza granicami państwa”, Dz.U. 1998 nr 162 poz. 1117, ISAP [online].

„Ustawa z dnia 11 marca 2022 r. o obronie Ojczyzny”, op.cit.

The number of professional soldiers in the Polish armed forces has undergone moderate changes in recent years, as confirmed by official data from the Ministry of Defence. In 2015, the number of professional soldiers was 96,200, rising steadily in subsequent years to 107,700 in 2019, 110,100 in 2020 and 118,300 in 2022, including 11,500 women. Stability has also been maintained in the employment of the army’s civilian employees, whose number was 45,500 in 2015. This number has risen to 45,800 in 2019 and 46,600 in 2020, with 46,500 civilian employees, including 21,500 women registered in 2022. The structure of the career military corps at 31 December 2022 comprised 10,000 senior and general officers, 11,600 junior officers, 46,000 ensigns and non-commissioned officers and 50,700 soldiers. In addition, there were 7,000 soldiers on midshipman service and 31,730 soldiers on territorial military service.

An important factor influencing this trend is the retirement system in force, which allows pension rights to be acquired after 25 years of service, or even after just 15 years for those who joined before the reform.

According to article 26 of the Constitution, the Armed forces of the Republic of Poland ‘serve to protect the independence of the State and the indivisibility of its territory and to ensure the security and inviolability of its borders.’27 The Defence of the Homeland Act of 11 March 2022 also states that ‘the armed forces shall safeguard the sovereignty and independence of the State, its security and its peace.’28 According to this law, the armed forces may therefore be involved in activities that go beyond defending the national territory, including fighting against natural disasters and sorting out their consequences, anti-terrorist activities, protecting goods, search and rescue operations, the protection of health and human life, the defence of cyberspace, the neutralisation of explosives and crisis management. The ‘Act on the Principles of Use or Stay of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland Outside the Country’s Borders’ sets out the conditions for their use abroad.29 The Polish armed forces may be deployed in military operations in support of allied states or peacekeeping operations, anti-terrorist operations, in the evacuation of Polish citizens, and may also participate in humanitarian, search and rescue, training and representation missions. Other provisions govern the specific tasks of the Polish armed forces in crisis situations, border protection, support for the activities of border guards and police, and securing ships and seaports. The Polish armed forces are made up of five types of troops: land forces, navy, air force, special forces and territorial defence forces. Each of the armed forces is headed by the General Commander of the Armed Forces (General Marek Sokołowski), the Operational Commander of the types of Armed Forces (Major General Maciej Klisz) and the Commander of the Territorial Defence Forces (Brigadier General Krzysztof Stańczyk).

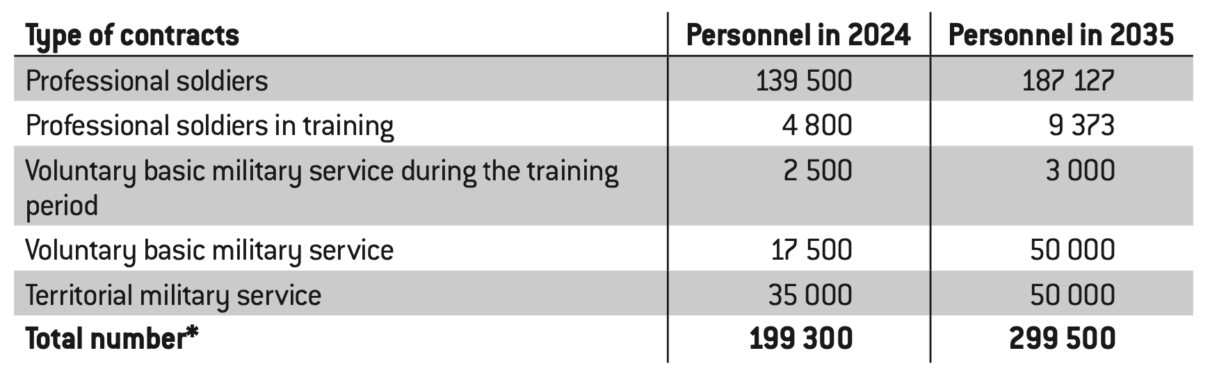

The Technical Modernisation Plan for 2021-203530 provides record funding of PLN 524 billion for the long-term implementation of modernisation programmes that play a key role in developing the Polish Army’s operational capabilities. The legal basis for the process of expanding the modern armed forces is the Act on the Defence of the Fatherland.31 This law provides for a gradual increase in the size of the armed forces from 200,000 to 300,000 soldiers by 2035 (see Table 6), which could make it the largest land army in Europe.32 Increasing the size of the armed forces, both in terms of professional soldiers and support formations, is part of a long-term strategy to modernise and develop Poland’s defence potential. The figure of 300,000 soldiers includes 187,127 professional soldiers, 9,373 professional soldiers in training, 3,000 volunteer soldiers in training, 50,000 soldiers on voluntary military service and 50,000 soldiers on territorial military service. The implementation of this ambitious plan could face major difficulties, linked in particular to demographic and budgetary factors which could limit the capacity to increase the number of professional soldiers. Although there has been a gradual increase in the size of the army in recent years, a high attrition rate remains a challenge.33 According to data from the Ministry of Defence, in January 2023, 4,300 soldiers left the army, in January 2024 the figure was 4,500, but by January 2025 the number had fallen to 2,700.

It should also be noted that Poland participates in international operations, committing 1,500 soldiers to ten peacekeeping missions or military operations on different continents.34 Poland’s participation in these missions underlines its active involvement in stabilising the international situation and cooperation within politico-military alliances.

Table 5: the Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland (2024-2035)

Source :

Ministry of National Defence.

*Army in peacetime

Russia’s hybrid war

Stanisław Koziej, „Wojna hybrydowa: zimna i gorąca”, 2018 [online] ; Stanisław Koziej, „Nowa, hybrydowa zimna wojna w Europie a bezpieczeństwo Polski”, 2016 [online].

Katarzyna Zdanowicz, „Presja migracyjna na granicy polsko-białoruskiej”, Podlasie Border Guard, 2 April 2025 [online].

Dariusz Materniak, „„Zapad ‘25”: ograniczone, ale jednak możliwości”, Polska Zbrojna, 12 February 2025 [online].

An upsurge in hybrid activity was observed in 2023, in connection with the parliamentary elections held that year.

Go further: „Raport cząstkowy Zespołu ds. Dezinformacji. Komisja do spraw badania wpływów rosyjskich i białoruskich na bezpieczeństwo wewnętrzne i interesy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w latach 2004–2024”, 10 January 2025 [online]; Kazimierz Wóycicki, Marta Kowalska et Adam Lelonek „Rosyjska wojna dezinformacyjna przeciwko Polsce”, Fundacja Pulaski, 2017 [online]; See also cases of disinformation regularly observed by Polish intelligence „Polska na celowniku dezinformacji”, gov.pl, 2025 [online] „Dezinformacja przeciwko Polsce. Meldunki sytuacyjne”, gov.pl [online].

According to ESET’s Threat Report for the second half of 2024, Poland is the second most attacked country in the world, after Japan. “Threat Report H2 2024”, Eset Digital Security, 2024 [online].

On 10 July 2023, the University of War Studies, Poland’s largest military university, was the victim of an attack carried out by the CyberTriad group, a group linked to the Russian intelligence services. See Nikola Bochyńska, „Nowe szczegóły cyberataku na Akademię Sztuki Wojennej”, CyberDefense24, 24 August 2023 [online].

Zarzut za podpalenie marketu budowlanego na zlecenie rosyjskiego wywiadu”, National Prosecutor, 12 March 2025 [online].

„Komunikat dotyczący działalności dywersyjnej FR”, Internal Security Agency, 25 October 2024 [online].

The ‘phantom fleet’ is a network of tankers that enables Russia to export oil despite Western sanctions. It operates through the purchase of old ships by intermediaries from third countries, and takes advantage of legal loopholes in international trade and in the recruitment of crews, particularly from the EU and Ukraine. More than a third of these ships previously belonged to Western companies officially supporting the sanctions In addition to financing Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the ‘phantom fleet’ poses environmental and security risks – spying devices have been discovered on some tankers. The EU is considering extending sanctions not only to ships, but also to agencies and key personnel, which could compromise the fleet’s operational capacity. Units of the fleet are therefore suspected of being involved in acts of sabotage and damaging essential underwater infrastructure in the region. In response, NATO’s Baltic member Sstates have launched Operation Baltic Sentry – an operation to strengthen the surveillance and protection of submarine infrastructures. This action is part of a strategy to combat hybrid threats, focused on detecting and preventing acts of sabotage in the Baltic Sea. “Baltic Sentry, a new NATO activity for safer critical infrastructure”, NATO, 14 January 2025 [online] NATO – News: NATO launches ‘Baltic Sentry’ to increase critical infrastructure security, 14-Jan.-2025; Eitvydas Bajarūnas, “Choking Russia’s Shadow Fleet in the Baltic”, CEPA, 15 January 2025 [online] ; Damian Szacawa et Jakub Bormio, „‚Wartownik Bałtyku’ – odpowiedź NATO na działania sabotażowe Rosji na Bałtyku”, Komentarze IEŚ, 1267, 2025 [online].

The hybrid war waged by Russia and Belarus has become much more acute since 2014 and is forcing Poland to strengthen its defence. Combining traditional military methods with non-military actions,35 this war threatens the stability of the country and the region as a whole. There are many examples of hybrid actions:

– Using migration as an instrument of destabilisation. Since 2021, Poland has been facing a migration crisis on its Eastern border. It is the result of a Belarusian strategy, supported by the Russian government, to bring migrants from the Middle East (mainly from Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, India, Iran and Yemen) to the Polish border, using them as a ‘weapon’ to destabilise the EU’s borders. Every week, Polish border guards record an average of 100 attempts to cross the border illegally.36

– Regular joint military manoeuvres between Belarus and Russia: the latest took place near Grodno, close to the Suwałki corridor, from 29 to 31 July 2023. The next manoeuvre is scheduled for September 2025 (Zapad 2025 exercises37). The military exercises near Poland’s borders are evidence of the growing military threat from Russia and Belarus. They not only test military capabilities, but above all destabilise the situation in the region by deliberately provoking a sense of threat in neighbouring countries.

– The presence of the paramilitary group Wagner in 202338 near the Polish border with Belarus: this has given rise to particular concerns about a possible escalation of hybrid activities, such as sabotage, disinformation and provocations on Polish territory.

– Information warfare: disinformation and manipulation of information are used to destabilise the country internally and to undermine Poland’s image abroad.39

– Cyber attacks: in 2024, Poland recorded an average of 5,000 cyber attacks per day, making it one of the most attacked countries in Europe.40 The main victims were government institutions, the financial sector, hospitals and higher education,41 as well as critical infrastructure such as railways and energy networks.

– Sabotage activities: in 2024, numerous fires (critical infrastructure, hospitals, railways) were caused by sabotage activities.42

– Spying activities: the presence and activity of Russian and Belarusian spies, gathering intelligence and supporting internal destabilisation, is increasingly significant.43

– The Russian ‘phantom fleet’: it is stepping up its activities in the Baltic Sea, damaging the region’s essential submarine infrastructures.44

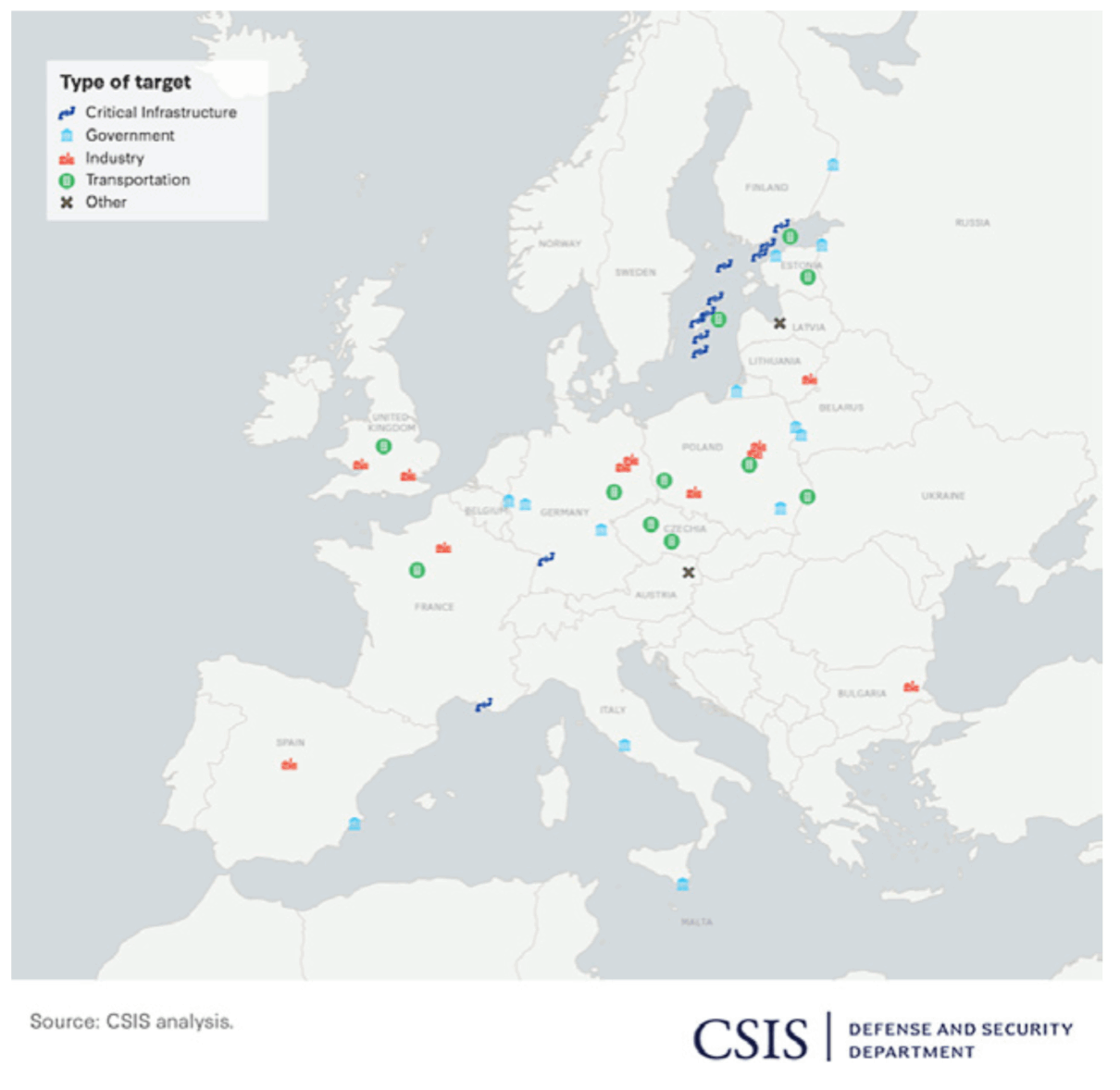

Poland is on the front line of the hybrid war. It is facing numerous threats aimed at destabilising the state and its environment, as illustrated in Figure 5. During the presidential campaign in Poland, networks of fake accounts linked to Russian interests were identified. They disseminated disinformation on subjects such as the war in Ukraine, migration and relations with the European Union. The aim was to increase social divisions and undermine confidence in certain candidates and institutions. Recurring pro-Russian narratives were relayed, in particular the idea that only Russia was genuinely seeking peace. Specific operations were also identified, such as Overload (information overload) and Doppelganger (impersonation of credible media).45

Figure 1: Russian attacks in Europe, 2022-2025

Source :

Seth G. Jones, ‘Russia’s Shadow War Against the West’, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 18 March 2025 [online].

The ‘Eastern Shield’ (Tarcza Wschód)

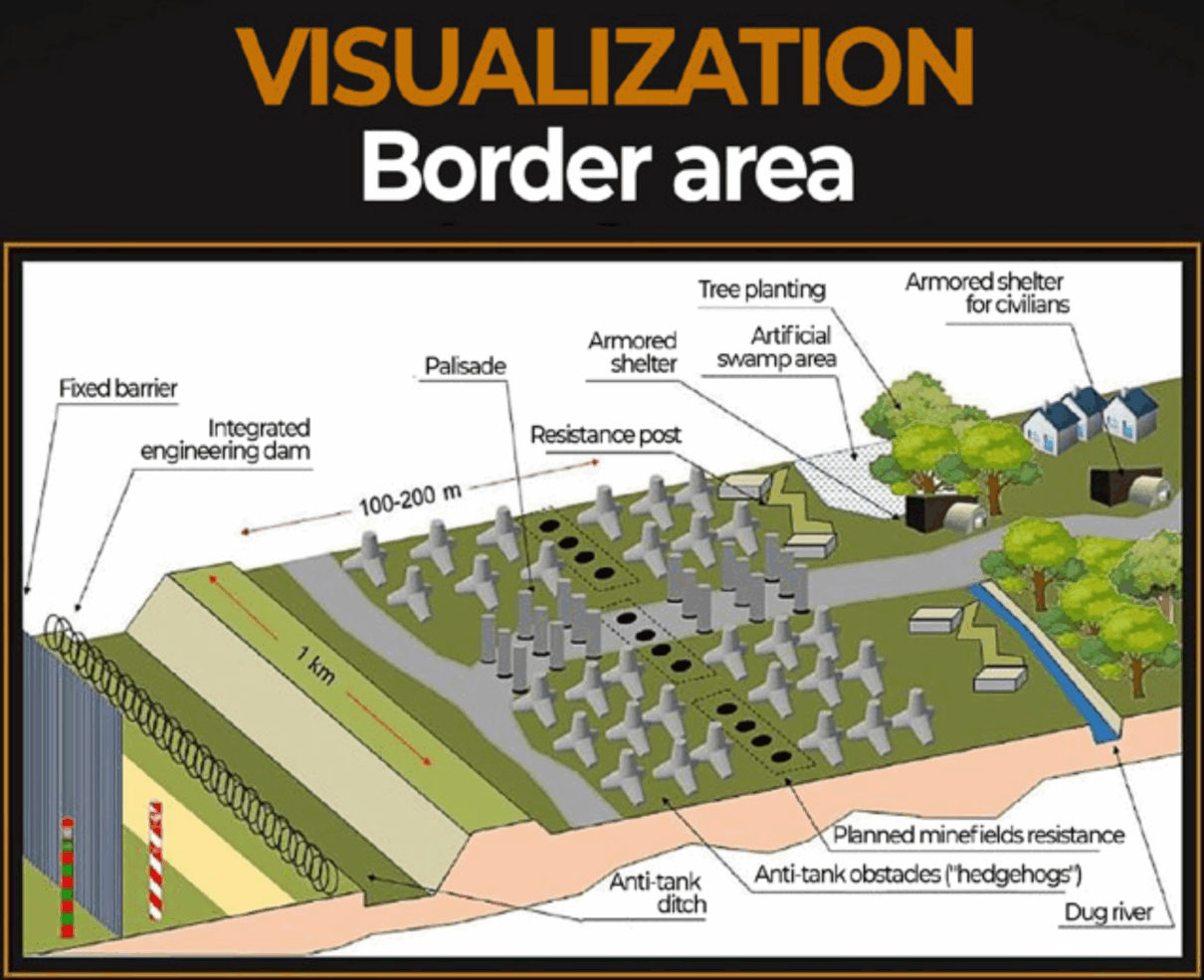

In addition to the measures described above, Poland has responded to those security threats by adopting the national deterrence and defence project ‘Eastern Shield 2024-2028’46 (Tarcza Wschód). This is a key initiative for strengthening Poland’s and NATO’s Eastern flank’s security. Annonced in May 2024, the project includes building fortifications on the border with Russia and Belarus, a system of military fortifications, physical barriers and modern airspace surveillance systems. Implementation is scheduled for 2024-2028, with a budget of PLN 10 billion.

Figure 2: Visualisation of a section of the ‘Eastern Shield’ 2024-2028 national defence and deterrence project – border belt

Source :

Tarcza Wschód [online].

Its strategic importance for the protection of the EU’s eastern border was highlighted, particularly in the context of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. The decision was adopted as part of an amendment to the resolution on the White Paper on the future of European defence, proposed by the Group of the European People’s Party (EPP). The amendment stresses the importance of protecting the EU’s land, air and sea borders, particularly in the East, as a major element in the security of the Community as a whole. “The Eastern Shield and the Baltic Defence Line should become EU flagship projects to support deterrence and counter potential threats from the East”. See “European Parliament resolution of 12 March 2025 on the White Paper on the future of European defence”, European Parliament, 12 March 2025 [online].

The basic principle of the ‘Eastern Shield’ is to strengthen deterrence capabilities, hinder enemy movements and ensure the smooth movement of its own forces. In this context, the programme includes the construction of defence infrastructures such as anti-tank ditches, barrage systems, bunkers and warehouses for storing military equipment. These elements are intended to form a complete defence system, integrated with the existing dam on the Polish-Belarusian border and the «Baltic Defence Line» currently being built by the Baltic States. The programme is also strategic for strengthening Poland’s and NATO’s reconnaissance capabilities. The initiative involves extending detection systems, including sensors, cameras and satellite infrastructure. The upgrade will also include anti-drone systems, in line with global trends in defence against asymmetric threats. The project is designed to both deter and protect civilians. New military and defensive infrastructures will contribute to the stability of the region and strengthen Poland’s role in the European and transatlantic security architecture. The European Parliament acknowledged the crucial importance of this project for common security at a plenary session in Brussels on 12 March 2025, and as a key initiative for the common security of the European Union.47 The European Commission describes the project in its White Paper as ‘a critical area for the rearmament of Europe’ (19 March 2025).48

Regional cooperation, a pillar of Poland’s security

It should be noted that the creation of the Visegrad Battle Group (EU BG V4) in 2015 at the V4 Summit in Budapest is an example of regional defence cooperation. Its creation was an important step towards closer military cooperation between the V4 countries. Subsequent editions of the Battle Group have been launched in 2019, 2023 and 2024, each involving Polish military units, including the 6th Airborne Brigade. See Jakub Bornion, „Rozwój współpracy wojskowej państw Grupy Wyszehradzkiej w ramach jednostek międzynarodowych w 2023 roku”, Komentarze IEŚ, 952, 18 September 2023 [online] Krzysztof Rybicki, „Inauguracja dyżuru Dowództwa Operacji Unii Europejskiej państw Grupy Wyszehradzkiej (EU OHQ BG V4 2023/I) i Grupy Bojowej Unii Europejskiej 2023-1 (EU BG V4)”, Polish Army [online] „V4 Trust—Program for the Czech Presidency of the Visegrad Group (July 2015-June 2016)», Visegrad Group [online].

The Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) is a regional military alliance formed in 2002 by the six Sstates of the former USSR under the 1992 Treaty of Tashkent. The organisation operates according to the principles of collective security, assuming mutual defence in the event of external aggression. It comprises Russia, Belarus, Armenia (suspended), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, while Azerbaijan, Georgia and Uzbekistan have withdrawn from the organisation. The CSTO regularly conducts military exercises, mainly under the aegis of Russia, and set up a rapid reaction force in 2008. The organisation intervened in Kazakhstan in 2022 at the request of the country’s president following mass demonstrations. The CSTO is also faced with internal crises, such as political disputes between its members, like the suspension of Armenia’s membership. The alliance is a tool for Russia’s influence in the region, but its effectiveness and coherence are controversial. See Michał Patryk Sadłowski, Organizacja Układu o Bezpieczeństwie Zbiorowym. Prawno-instytucjonalne aspekty funkcjonowania, Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, 2017 ; Agnieszka Legucka, “Russia and the CSTO in the Face of Destabilisation in the Neighbourhood”, Polish Institute of International Affairs, 25 novembre 2020 [online].

Amélie Zima, « La politique de défense de la Pologne dans le contexte du Brexit : Bilatérale, multilatérale ou flexilatérale ? », Politique européenne, No. 70, 2020, pp. 116-143 [online].

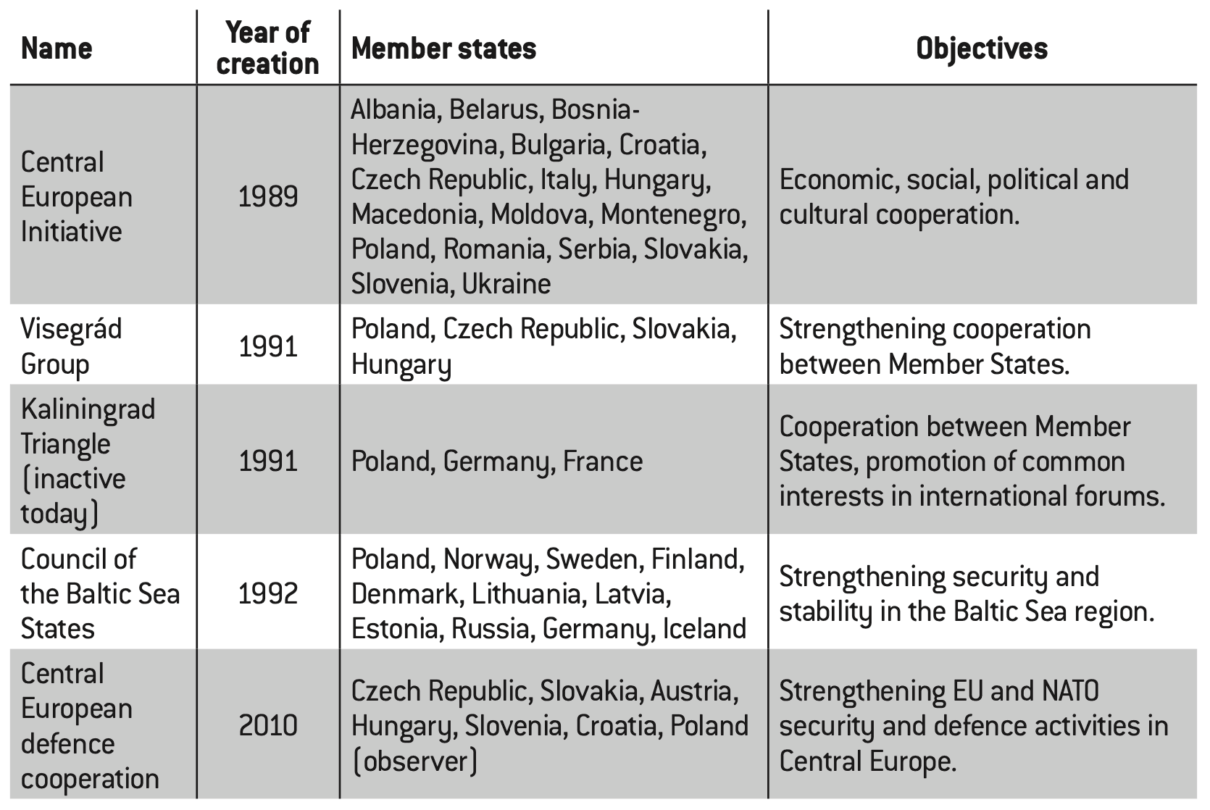

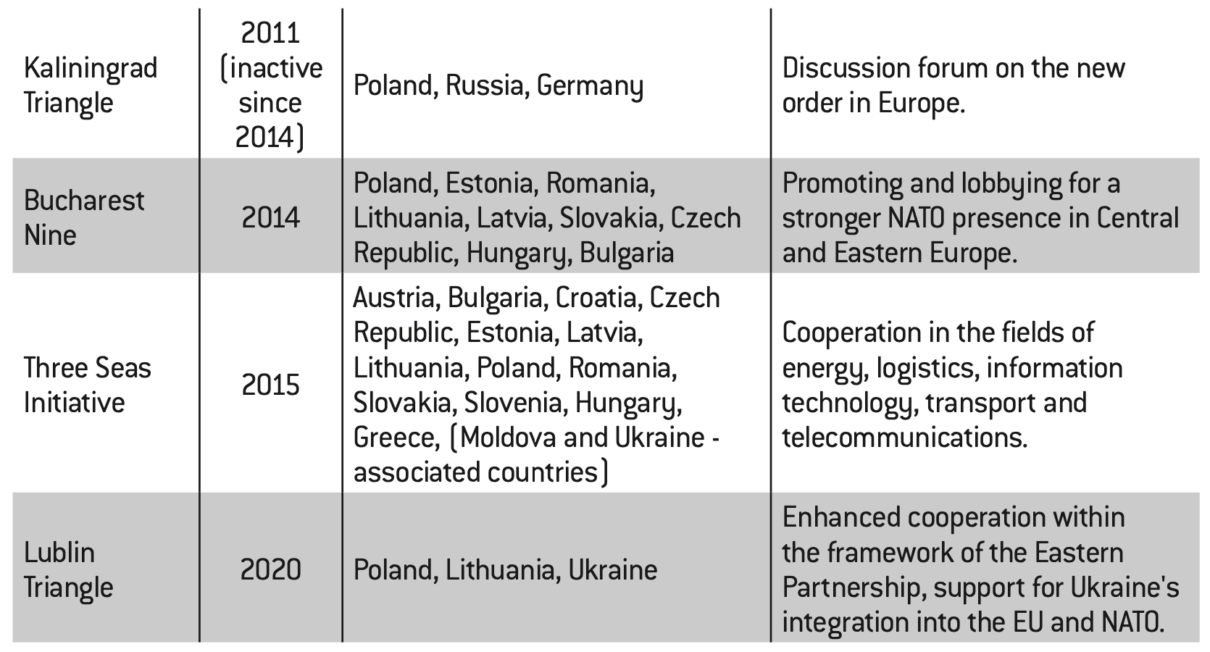

In addition to the national dimension of Poland’s security, the Euro-Atlantic and regional dimensions are also important. Together, they create the guidelines for the development of defence, forming the basis of a global vision of Poland’s international security. Partnerships with the United States, NATO and the EU form the basis of Polish foreign and security policy, although this does not detract from Poland’s attachment to regional alliances (see Table 7)49. These various forms of cooperation and dialogue demonstrate the pivotal role Poland has played and continues to play in Central and Eastern Europe, where the issue of geopolitical and military security remains a primary concern. It should be noted that Poland lies between NATO’s eastern flank (comprising Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia) and Central Europe (Poland, Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia). It also lies on the border between NATO and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO50), underlining its strategic importance in the European security system.

Poland has been trying for some years to reactivate existing forms of political and defence cooperation or to create new ones, as Table 7 shows. These activities are aimed at strengthening the position of these States on the European stage, with an emphasis on regional solidarity, underpinned by the region’s economic growth. IFRI researcher Amélie Zima describes this approach as ‘flexilateralism’, which encompasses three levels of cooperation: bilateral, multilateral within NATO and multilateral within the European Union.51 This concept, first defined by Samuel B. H. Faure, refers to a state policy of simultaneously implementing various forms of international cooperation52.

Table 6: Poland’s main participation in regional cooperation organisations/forums

Source :

analysis by the author.

Regional cooperation helps to ensure Poland’s security, as illustrated by the forms of cooperation described above. By strengthening its relations with its regional allies, Poland is placing itself at the heart of the construction of the European security architecture. ‘Flexilateralism’ allows policy to be adapted flexibly to changing conditions, making Poland one of the leaders in regional defence cooperation. This allows Poland to go beyond a position of mere beneficiary to take the lead on security matters.

Poland’s role in the European security system

Magdalena el Ghamari, Teresa Usewicz, Kinga Torbicka, “Common Security and Defense Policy of the European Union Through the Prism of Polish Experiences and Security Interests”, Polish Political Science Yearbook, 2021 [online].

Stała współpraca strukturalna w dziedzinie obrony i bezpieczeństwa (PESCO), Eur-Lex, 8 september 2023 [online].

European Joint Integrated Training and Simulation Centre (EUROSIM); Special Operations Forces Medical Training Centre (SMTC); Integrated Unmanned Ground System (iUGS); Maritime (Semi-) Autonomous Mine Countermeasures Systems (MAS MCM); Harbour and Maritime Surveillance and Protection (HARMSPRO); European Secure Software Radio (ESSOR) ; Rapid Reaction Teams and Cyber Security Mutual Assistance (CRRT); European Medical Command (EMC); Network of Logistics Platforms in Europe and Support to Operations (NetLogHubs); Military Mobility; EU Collaborative Warfare Capabilities (ECoWAR); EU Radio Navigation Solution (EURAS); Defence of Space Assets (DoSA).

“Statement by President von der Leyen on the defence package”, European Commission, 4 March 2025 [online].

Over the years, Poland’s participation in the development of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) has been seen as a counterpoint to its commitment to NATO.53 To this day, it remains complementary to allied commitments. Poland is committed to permanent structured cooperation in defence and security (PESCO),54 but remains sceptical about the European Defence Fund. It fears that such programme would weaken transatlantic ties and duplicate NATO structures, which Poland considers to be the pillar of its security. Poland is also concerned about the way in which funding from the Fund is allocated, as it favours countries with a developed defence industrial sector. Such attributions could thus exacerbate inequalities within the European Union. Furthermore, Poland also participates in thirteen PESCO initiatives55.

Nevertheless, the Polish Presidency of the Council of the EU (from 1 January to 30 June 2025) has set security and defence in Europe as its top objective. This commitment may reflect Poland’s desire to align with European mechanisms of defence construction. A series of geostrategic elements point towards a common continental defence policy: the international situation (including the crisis in transatlantic relations), the war in Ukraine, now in its third year, and the desire to emphasise the role of NATO’s Eastern flank States in the security of the continent as a whole. Announced by the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen56 and approved by the European Parliament,57 ReArm Europe has allocated around €800 billion to strengthen the EU’s defence capabilities. Among other things, the initiative includes a new loan mechanism that will provide €150 billion to Member States for investment in defence, facilitating joint purchases of military equipment and increasing the inter-operability of the EU’s armed forces. For Poland, this is an opportunity to intensify cooperation with partners in the region and to strengthen its own defence capabilities by participating in joint programmes and common armaments initiatives, thereby increasing its participation in the development of the EU’s CSDP.

| Treaty of Nancy

Signed on 9 May 2025, the Treaty of Nancy marks a new stage in Franco-Polish relations and takes bilateral cooperation to an unprecedented level of strategic partnership and mutual trust. It includes reciprocal security guarantees, providing assistance – including military assistance – in the event of an attack against one of the two countries. The agreement covers a wide range of areas of cooperation, from common defence policy to cyber security, the arms industry and enhanced intelligence cooperation. The assurance of direct military support from France – a nuclear power – significantly strengthens Poland’s security and deterrence mechanisms on NATO’s Eastern flank. At the same time, it represents a valuable contribution to the European security system, confronted to the Russian threat. Thanks to this agreement, Poland joins the select circle of strategic partners closest to Paris (alongside Germany, Italy and Spain, among others), consolidating its position in Europe as an essential pillar of stability on the EU’s and NATO’s eastern flank. In the long term, the Treaty of Nancy is part of the vision of European strategic autonomy, deepening defence cooperation within the EU and reducing the continent’s dependence on US support in the field of security. This reinforced security cooperation between Paris and Warsaw also contributes to a greater integration of Central and Eastern European countries into the EU security policy. Source: „Przełomowy traktat polsko-francuski podpisany w Nancy”, Chancellery of the President of the Prime Minister, 9 May 2025 [online]. |

The transatlantic dimension of Poland’s security

According to the National Security Strategy of the Republic of Poland (2020), NATO and the US are strategic partnerships. Polish society’s strong attachment to American security guarantees is rooted in a series of historical, geopolitical and psychological factors. Occupied several times and abandonned by Western powers in the 20th century, Poland sees the alliance with the United States as a concrete guarantee of security. The American military presence on Polish soil is seen as a deterrent to the Russian threat. Moreover, public opinion often associates the US with the defence of national sovereignty and strategic reliability.

Poland in NATO

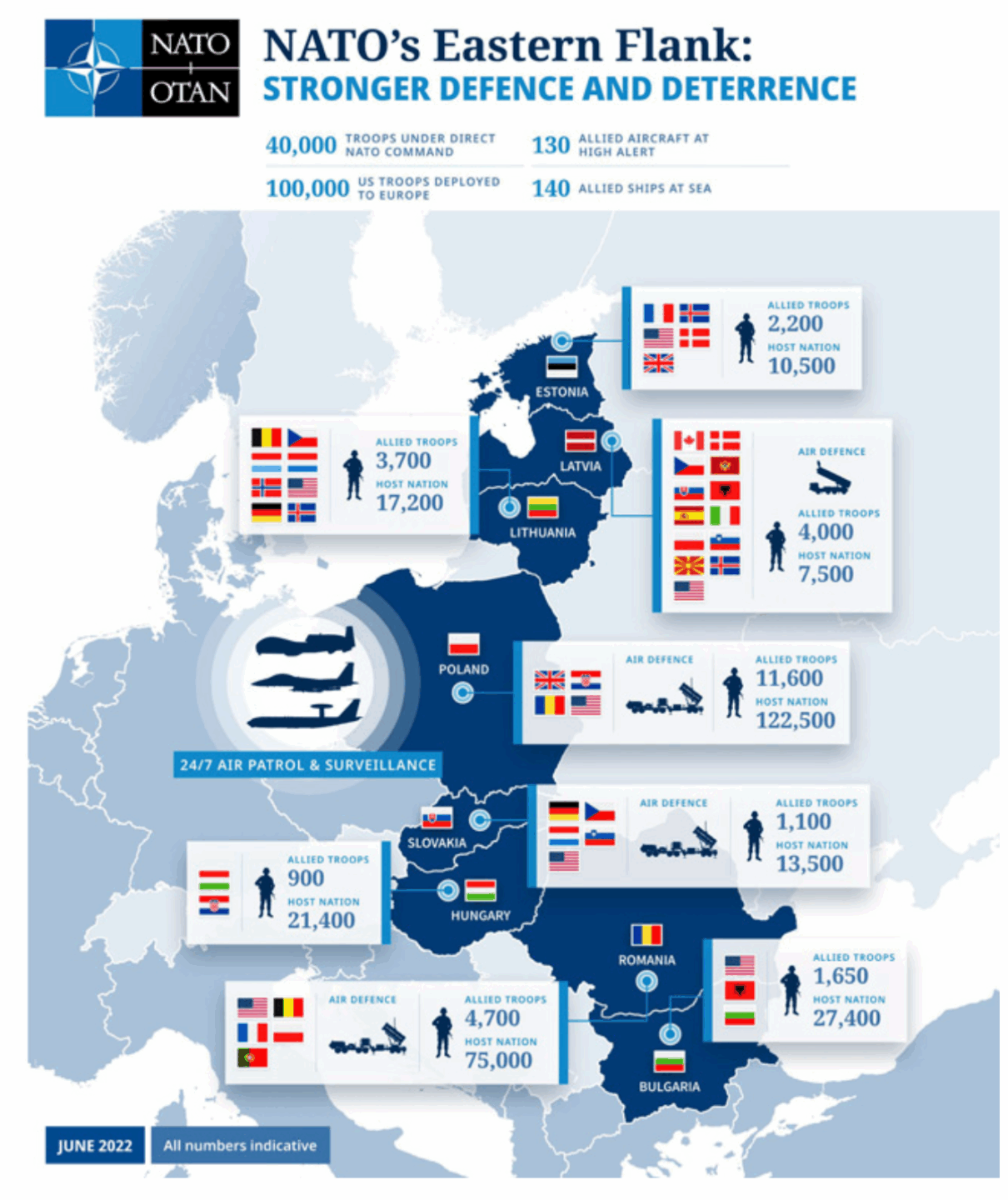

Between 2014 and 2025, NATO’s Eastern flank acquired crucial importance for the security of Poland and the entire Euro-Atlantic region. As a country bordering Russia (Kaliningrad Oblast), Belarus and Ukraine, Poland is at the forefront of potential threats and destabilisation linked to the Kremlin’s aggressive policies. The war in Ukraine, which has been going on since 2014, has prompted NATO to strengthen the defence capabilities of its Eastern member states. Following the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the North Atlantic Alliance identified Russia as a threat to European security. This was reflected in decisions taken at successive NATO summits – in Newport (2014), Warsaw (2016), Brussels (2018), Vilnius (2023) and Washington (2024).

The 2014 Newport Summit launched the implementation of the Readiness Action Plan (RAP), which includes: the creation of the Very Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF), NATO’s spearhead, capable of rapid deployment, the increase in operational capabilities of the Multinational Corps Northeast (MNC NE) in Szczecin, and the intensification of military exercises in Central and Eastern Europe (including Anaconda-16 with 31,000 soldiers).

Decisions taken at the NATO Warsaw Summit in 2016 strengthened defence commitments by establishing NATO Battlegroups in Poland and the Baltic States. In Poland, the US assumed command responsibility by deploying its troops to the Orzysz and Bemowo Piszki regions. Subsequently, the 2018 NATO summit in Brussels adopted the so-called «4×30» initiative, aimed at enhancing military readiness by planning to deploy 30 battalions, 30 air squadrons and 30 ships within 30 days.58 This is a further step towards the unity of the Alliance and deterrence against Russia. The last two NATO summits, in Vilnius (2023) and Washington (2024), focused on strengthening defence and deterrence capabilities. In the Lithuanian capital, decisions were taken to extend the presence of NATO battalions to brigade level, strengthen air and missile defence, develop regional defence plans that take account of the specific characteristics of Baltic and Central Europe, and increase Germany’s military presence in Lithuania and Canada’s in Latvia. In Washington, as part of its strategy of deterrence against Russia, the Alliance has decided to provide long-term support for Ukraine. Financial commitments of €40 billion a year and a plan for the deployment of long-range missile systems by the US and Germany by 2026 have been adopted. Poland is participating in the development of the NATO-Ukraine Joint Analysis, Training and Education Centre (JATEC).59 Further decisions could be taken at the next NATO summit in The Hague in 2025.

Figure 3: NATO’s Eastern flank on 22 March 2022

Source :

official website of NATO [online].

Polish President Andrzej Duda has proposed an increase in defence spending by NATO member States to 3% of GDP per year. „Prezydent RP: Państwa członkowskie NATO muszą podnieść wydatki na obronę do 3 proc. PKB”, official website of the President of the Republic of Poland, 11 March 2024 [online].

As a security leader on NATO’s Eastern flank, Poland is playing an increasingly important role within NATO structures, as evidenced by the increase in defence spending, which will reach 4.7% of GDP in 2025 – the highest share among NATO countries.60 It is also actively involved in air defence initiatives, notably as part of the DIAMOND programme (Delivering Integrated Air and Missile Operational Networked Defences61), which aims to strengthen air defence capabilities. Of paramount importance is Poland’s cooperation with the US as part of the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), in which US units are stationed in Poland, including the US Fifth Corps headquarters in Poznań., is also of key importance. Warsaw is officially in favour of integrating its Eastern neighbour, Ukraine, into NATO, believing that its membership will ultimately enhance security in the region. At the NATO summit in Vilnius, it was stressed that Ukraine did not need a Membership Action Plan (MAP), a decision which could accelerate the process of joining NATO. Poland also supported the transformation of the NATO-Ukraine Commission into the NATO-Ukraine Council, thereby strengthening formal cooperation mechanisms.

Poland takes part in NATO initiatives, including the Baltic Air Policing (BAP) mission. Launched in 2004, this mission protects the airspace of the Baltic States. Poland, which has been involved since 2005, is one of the most committed participants in this operation. Between 2017 and 2023, there were between 100 and 300 violations of Baltic airspace by Russian aircraft. In 2023, Poland participated in the 63rd rotation of the NATO Sky Police and, from 1st November 2023 to 31 February 2024, the Polish contingent Orlik XII was stationed at a base in Šiauliai, Lithuania, to monitor the airspace of the region.62

Cooperation between Poland and the United States

„Obecność w Polsce wojsk USA zwiększa nasze bezpieczeństwo”, Ministry of National Defence, 28 October 2018 [online].

“Address by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly”, Warsaw, Poland, 2018 [online].

General Ben Hodges was the Commander-in-Chief of US Land Forces Europe from 2014 to the end of 2017.

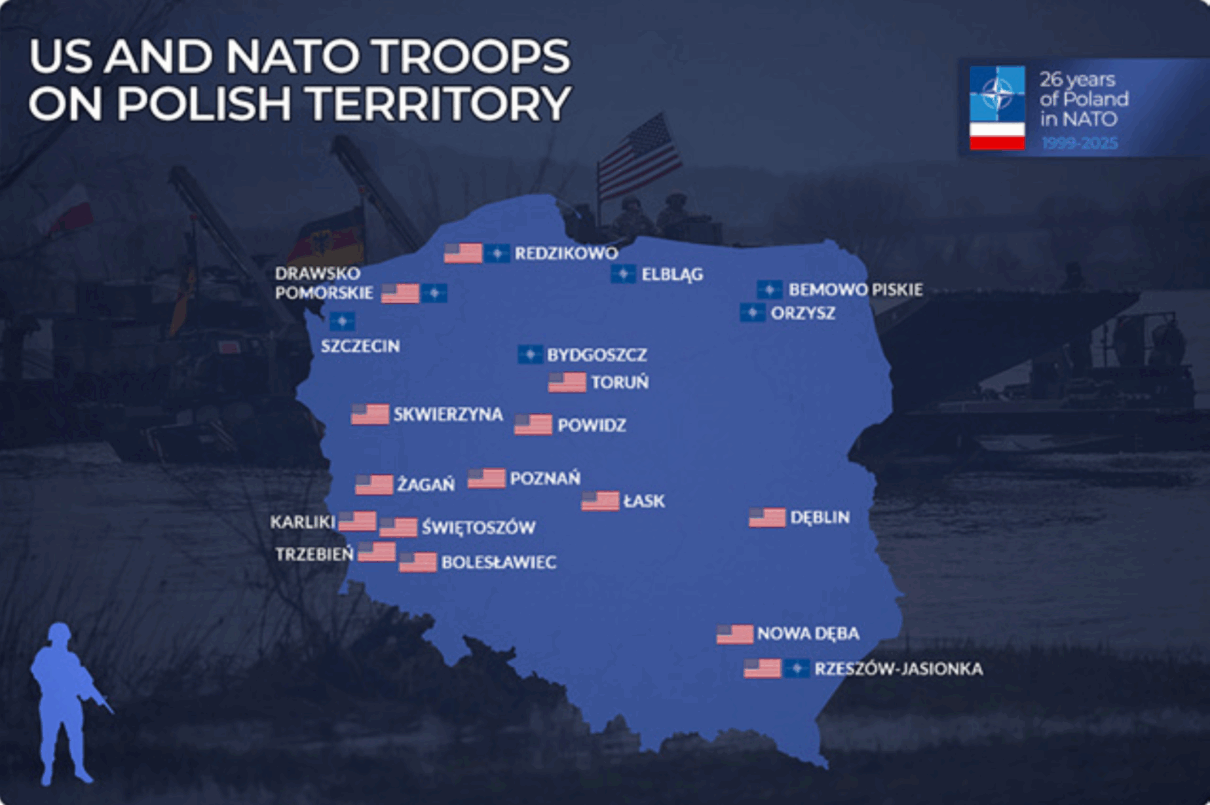

In 2019, the Polish government announced the Fort Trump initiative to increase the presence of US troops on Polish territory. The then Minister of National Defence, Mariusz Błaszczak, stressed out that the permanent presence of US troops in Poland strengthened the country’s security.63 At the 2018 NATO Parliamentary Assembly, Jens Stoltenberg declared that ‘a stronger Europe, means a stronger NATO’64, and emphasised on the need to strengthen the Eastern flank of the Alliance.

Among other reasons, concern over the security of the Suwałki Gap, crucial to the defence of Central and Eastern Europe, has prompted the US to strengthen their military presence in Poland. General Ben Hodges65 described the area as NATO’s ‘Achilles heel’66 and called for it to be stabilised.

| The Suwałki Gap

The Suwałki Gap is a key geopolitical point for Poland and NATO security on its Eastern flank, particularly in the context of current tensions with Russia and Belarus. It is a narrow strip of territory linking Poland to Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, while separating the Kaliningrad region from Belarus. The gap is of strategic importance as it is the only land link between these countries and NATO and the EU. Its geographical location makes it particularly vulnerable to potential military threats. Russia’s first attempts to exploit the Suwałki Gap came in the early 1990s, when Moscow proposed creating a transport corridor through Poland, which was firmly rejected by Warsaw. Nevertheless, the issue of the area’s importance in international relations, particularly in the context of EU enlargement, resurfaced in 2001-2002, when Russia again requested special transit rights. Over time, the corridor gained in importance. Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the escalation of tensions in the region, it became one of the most important points on NATO’s security map. Today, after the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the Suwałki corridor is known as «’the most dangerous place on earth». The heavy militarisation of the Kaliningrad region and the presence of the Wagner Group in Belarus increase the risk of hybrid incidents and activities in the area. Potential threats arise from the possibility of provocations and attempts to destabilise the situation in Poland and the Baltic States. Historical incidents, such as the violation of airspace by Belarusian helicopters or military aircraft accidents, testify to the real risk of conflict escalation in the region. The Suwałki Gap remains at the centre of international attention, being both a tipping point and a place of intense geopolitical rivalry. Its importance is increasing in the context of growing tensions in Central and Eastern Europe. It is therefore necessary to strengthen defence capabilities in the region and step up surveillance activities in order to prevent possible threats, including provocations and disinformation activities that could jeopardise the stability of NATO’s Eeastern flank. Sources: Jan Kowalczewski, „Znaczenie polityczno-militarne przesmyku suwalskiego”, Przegląd Geopolityczny, nr 25, 2018, p. 104-115 [online]; Tadeusz A. Kisielewski, Przesmyk suwalski Rosja kontra NATO, Rebis, 2017; Łukasz Zaleński, „Przesmyk w grze”, Polska Zbrojna, 13 June 2024 [online]. |

“Joint Declaration on Advancing Cooperation”, Official website of the President of the Republic of Poland, 23 September 2019 [online].

After intense negotiations, Presidents Donald Trump and Andrzej Duda signed a declaration on 12 June 2019 providing for an increased US military presence in Poland.67 It stipulated, among other things: the rotational presence of 4,500 US troops with the possibility of increasing their number by 1,000; Polish funding of necessary military infrastructure; the establishment of the US Army’s V(e) Corps Forward Command in Poznań; a Joint Combat Training Centre (JCTC) in Drawsko Pomorskie; the deployment of MQ-9 Reaper pilotless systems in Łask; the creation of an air base for US Army operational support; and finally the deployment of logistical and operational support units. At the 2022 NATO summit in Madrid, US President Joe Biden announced the decision to establish a permanent US military presence in Poland.68 One year later, almost 10,000 American soldiers are already stationed there, with a target of 20,000.

Figure 8: US and NATO troops on Polish territory (2024).

Source :

„Polska droga do NATO”, official website of the President of the Republic of Poland, 12 March 2025 [online] .

„Wstępna gotowość operacyjna elementów systemu WISŁA”, Ministry of National Defence, 18 December 2024 [online]; Umowa na logistyczne wzmocnienie PILICY podpisana!, Ministry of National Defence, 04 July 2024 [online]; Krzysztof Wilewski, „Pytania o europejską tarczę”, Polska Zbrojna, 26 April 2024 [online].

„Uchwała rządu o wyborze USA do pierwszej polskiej elektrowni jądrowej”, gov.pl, 30 November 2022 [online] ; „Rząd potwierdza strategiczne partnerstwo z USA przy budowie pierwszej elektrowni jądrowej w Polsce”, Ministry of Climate and Environment, 20 November 2022 [online] ; „Elektrownia atomowa w Polsce. Po wyborach w USA potrzebna nowa umowa”, money.pl, 07 November 2024 [online].

In addition, cooperation between Poland and the US includes the construction of the Pilica air defence system (short-range system up to 10 km, comprising 21 batteries), Narew (medium-range 10-50 km, with 23 batteries and 128 launchers) and Wisła (long-range 50-150 km, 8 batteries and 64 launchers of the Patriot system). As part of its technical modernisation in 2018, Poland signed a $4.75 billion contract to purchase Patriot systems. In 2023, it issued a call for tenders to the United States for a further six systems, to be delivered by 2028.69

American-Polish cooperation includes both a military presence and the modernisation of critical infrastructure. A key element of this cooperation is the construction of Poland’s first nuclear power plant,70 which will contribute to the country’s energy independence.

This investment strengthens transatlantic ties, extending beyond military issues to strategic sectors of the economy. The development of its defence system is enabling Poland to strengthen its role as a key NATO ally on the Eastern flank.

The war in Ukraine: a game changer for polish security

Zbigniew Brzeziński, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives, Pluriel, 1997.

On 23 June 2022, Ukraine was granted candidate status for EU membership and, in November 2023, the European Commission positively assessed the progress of Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia towards accession.

“The PESEL number is an eleven-digit numerical code that uniquely identifies a person. The number contains the date of birth, sex, a serial number and a control number. It is allocated by the minister responsible for computerisation”, Ministry of Digitisation [online] Polska pomoc dla Ukrainy – Wydarzenia – Biuro Bezpieczeństwa Narodowego; Every citizen of the Republic of Poland has a PESEL number. From 2022, PESEL numbers will be assigned to Ukrainian citizens who arrived on Polish territory after the outbreak of war in order to guarantee their access to financial aid. „Art. 4. Nadanie numeru PESEL obywatelowi Ukrainy, Pomoc obywatelom Ukrainy w związku z konfliktem zbrojnym na terytorium tego państwa”, Wolters Kluwer, 27 March 2025 [online].

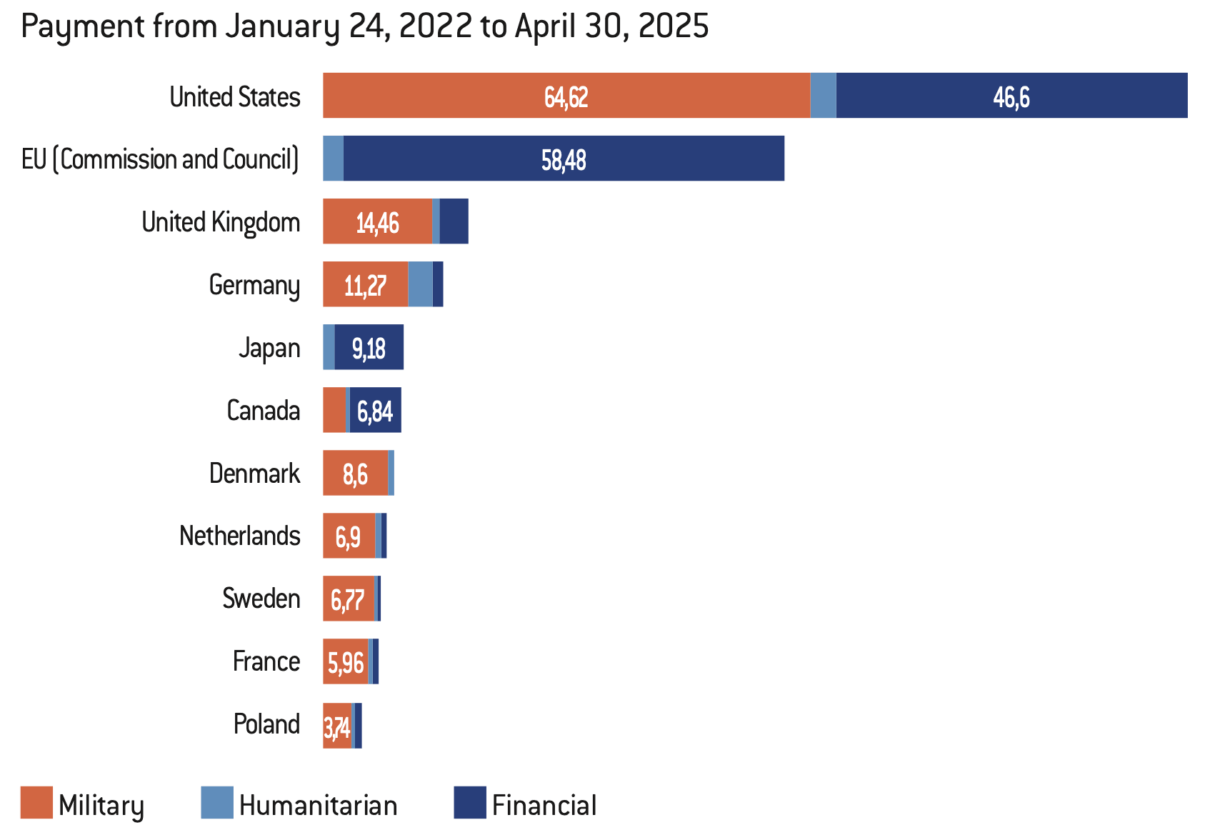

Back in 1997, Zbigniew Brzeziński, in his book The Grand Chessboard, stressed the importance of Ukraine in the reconfiguration of the geopolitics of Central and Eastern Europe.71 As a buffer zone between Russia and the rest of Europe, Ukraine has become essential to the stability of the region and a variable affecting Poland’s security in several respects: on energy security; on its relationship with Russia and the likelihood of a Russian attack on its territory. As a result, Poland has shown unconditional political, military, financial and humanitarian support to Ukraine.

The current armed conflict threatens European energy supplies, and especially Polish ones. The country is counting on the diversification of energy sources to minimise the effects of the war. Changing its energy policy in response to Russia’s threats since 2014 has become one of Poland’s main strategic objectives. In this context, Poland has taken three measures to implement its strategy. Firstly, the commissioning in 2015 of the Lech Kaczyński LNG terminal in Świnoujście enabled Poland to import liquefied natural gas from the US or Qatar, rather than from Russia. Secondly, the construction and commissioning of the Baltic Pipe pipeline in 2022 has opened up a new gas supply corridor from Norway, thus strengthening the country’s energy independence. Thirdly, Poland is stepping up its investment in renewable energies by developing wind and photovoltaic power, as part of both a diversification strategy and a long-term energy transition.

It is also worth mentioning the state of Polish-Russian relations, which is the result not only of history, but also of Poland’s geopolitical position. Russia aims to destabilise Central and Eastern Europe and continues to seek to undermine Western cohesion and alter the global security architecture. Since 1994, Russia has carried out numerous military interventions in Chechnya, Georgia, Ukraine (since 2014), and Syria, which not only affect the security of the region, but above all pose a direct threat to Poland.

It is important to stress that since the start of the armed conflict in 2014, Warsaw has consistently supported Ukraine’s desire to integrate into Euro-Atlantic structures.72 In addition to political support, Ukraine has received military, humanitarian and economic assistance from day one of the war. Poland supplied Ukraine with high-tech weapons, including Leopard 2A4 tanks, MiG-29 fighter aircraft, Piorun missile systems and Krab self-propelled guns. The total value of this military assistance reached about €3 billion in July 2023. Total economic aid amounts to €30 billion, or 1% of GDP, and humanitarian aid for refugees73 has reached €8 billion, Poland being the main host country for refugees from Ukraine. After three years of Russian aggression against Ukraine, almost a million Ukrainian citizens are enjoying temporary protection in Poland, mainly women and children. A total of 1.55 million foreigners have a valid residence permit, with Ukrainians accounting for 78% of newly settled foreigners. Currently, 993,000 people have received a PESEL number74 as part of temporary protection, 61% of whom are women and 77% adults.

In addition, 462,000 Ukrainians have a temporary residence permit, mainly related to work, and 92,000 have permanent resident status.

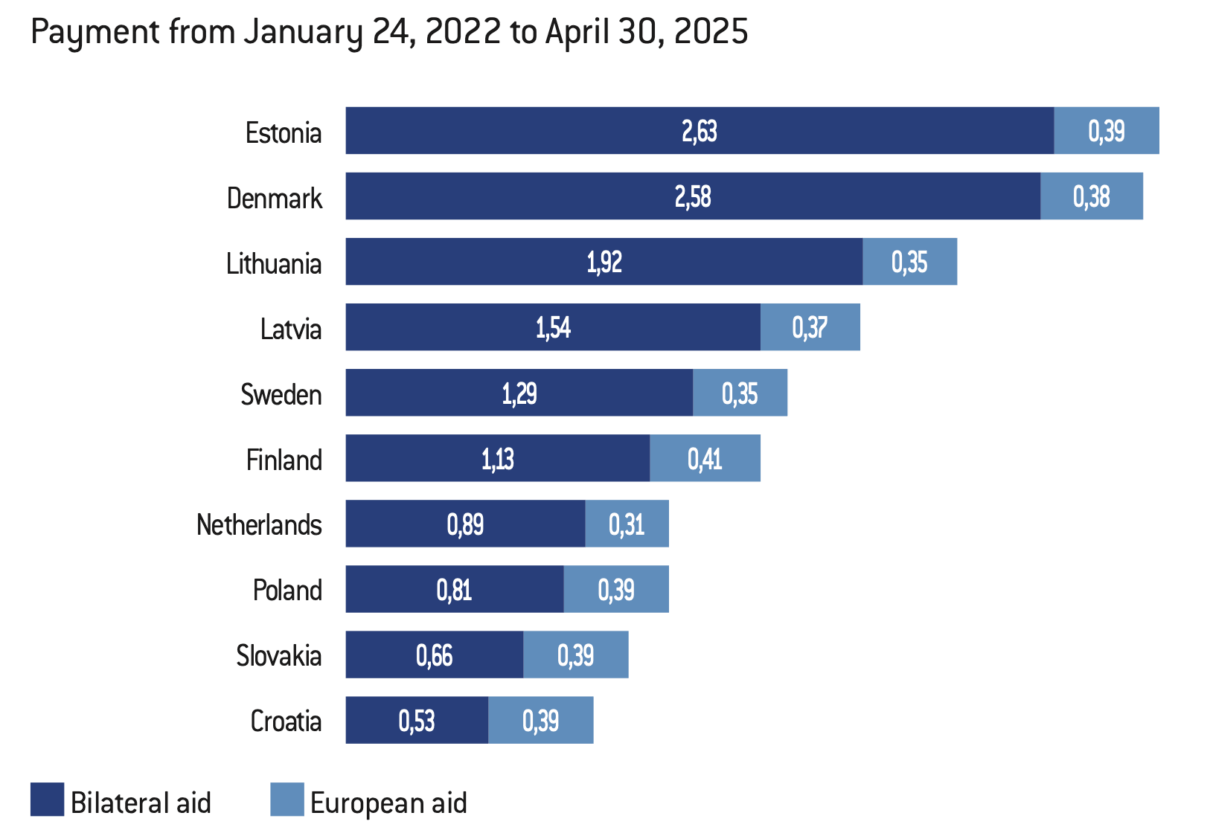

Figure 5: Government support to Ukraine by type of aid (in billions of euros)

Source :

Ukrainian Support Tracker, 2024 [online].

Figure 6: Government support to Ukraine as a percentage of GDP and European aid

Source :

Ukrainian Support Tracker, 2024 [online].

Although the likelihood of a direct Russian military attack on Poland is low, it cannot be completely ruled out. According to an opinion poll carried out in March 2024, 48% of Poles believe that Russia could attack Poland, while 41% consider it unlikely.75 Because of its proximity to Russia and Ukraine, Poland feels threatened, especially as the war is taking place on the other side of its eastern border. For this reason, Poland’s security depended on guarantees from its allies, in particular American support.

Poland’s support for Ukraine is not only a sign of solidarity with its neighbour, but also a strategic investment in its security and that of Europe as a whole, particularly in the context of the ongoing peace negotiations. Poland is heavily involved in military, economic and humanitarian assistance to Ukraine.

Bogdan Góralczyk at the scientific conference “Poland’s 20th anniversary in the European Union”, University of Warsaw, 15 March 2024.

Zbigniew Brzeziński, Strategic Vision : America and the Crisis of Global Power, Basic Books, 2012.

China-Central and Eastern European Cooperation – an international format of economic and diplomatic cooperation between China and 16 Central and Eastern European countries (including Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Serbia, and Croatia). Created in 2012, the initiative aimed to attract Chinese investment and develop trade and infrastructure in the region

Zbigniew Brzeziński, „Polska w okresie przemiany geostrategicznej”, based on a speech in Vienna at the National Defence Academy, Warsaw, 15 May 2002 [online].

On 18 March 2025, the Ministry of National Defence recommended that Poland withdraw from the Ottawa Convention, which deals with the use of anti-personnel mines.

Moral is to be understood here in the sense of psychological force and not morality in the sense of values. Józef Piłsudski said these words during a lecture entitled «The Commander-in-Chief and the State», given in Warsaw on 15 April 1926. In it, he stressed the importance of society’s ‘morale’ for the effective defence of the Sstate’s borders. Bohdan Urbankowski, Józef Piłsudski. Marzyciel i strateg, Zysk i s-ka, 2025.

Today’s world is undergoing a profound redefinition of international order: the gradual disappearance of the Cold War order, the decline of American hegemony and the evolution of globalisation are paving the way for a new multipolar balance. The rivalry between the superpowers – the United States, China and Russia – is shaping the global political scene, directly and indirectly affecting Poland’s security in these times of ‘geopolitical air currents’.76 Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2022, the resurgence of Russia’s neo-imperialist ambitions, as well as the tensions that have emerged in transatlantic relations at the start of President Donald Trump’s second term, make it essential for Poland to quickly and effectively redirect its strategic priorities to ensure its domestic security. As observed by Zbigniew Brzeziński, the US remains a key player – despite weaknesses –, without which international conflicts cannot be resolved.77 Thus, Poland’s strategic partnership with the US will evolve, but it is too early to determine its direction.

Cooperation within NATO and the EU and the strengthening of transatlantic ties remain the foundation of Poland’s international security. Its growing importance as a key player on the Alliance’s Eastern flank requires a further expansion of its defence capabilities and an increased US military presence on its territory. During its Presidency of the Council of the EU (January-June 2025), Poland took the lead on strengthening Europe’s strategic autonomy (the ReArm Europe plan and the extension of the ‘Eastern Shield’) to build an independent European security.

In the current situation, it is important to adapt to the paradigm shift in international relations, taking into account the growing importance of Asia. Cooperation with the countries of the Indo-Pacific, particularly in the field of new technologies and cyber security, should become a priority. China, although not a direct military threat, represents a real geopolitical challenge because of its global ambitions and its attitude towards Russia. Poland, for its part, needs to balance its interests skilfully without abandoning strategic cooperation with the US, while remaining cautious about Beijing’s influence (16+1 Initiative)78.

Strengthening regional alliances is also part of Poland’s security efforts.

The Three Seas Initiative, the Bucharest Nine and cooperation within the Visegràd group can help to increase the role of Central and Eastern Europe in international politics. As a regional leader, Poland is working to strengthen these structures while supporting Ukraine in its aspirations to join NATO and the EU.

Referring to Zbigniew Brzeziński’s statement twenty-three years ago: ‘The fundamental dilemma facing Poland is the persistence of the old historical threats, which, although receding, continue to weigh on its security. However, it is now the new dynamics of global security that are decisive for Poland. Despite this new dimension, historic threats remain painfully fresh in Polish memory. In the last three hundred years, Poland has known only thirty years without the presence of foreign (non-hostile) armed forces on its territory.’79 The diagnosis remains valid and ‘painful’. The modernisation of the armed forces, including an increase in defence spending, investment in modern military technologies, cyber defence and the development of territorial defence forces, military exercises, intensive training of reservists and a review of Poland’s withdrawal from the Ottawa Convention,80 all point to a return to thinking focused on the large-scale defence of the Sstate and the strengthening of deterrence. The motto of the Polish army, ‘God, Honour, Fatherland’, takes on a new meaning in these circumstances. It is not just a historical watchword, but rather a genuine foundation for mobilising society and rebuilding the State’s defensive spirit. In times of growing threats, the strength of a State is based on an assertive national identity, a strong sense of civic responsibility and a firm determination to defend its sovereignty. As Marshal Józef Piłsudski said: ‘To defend the borders of the State, a society must above all provide what is known in the language of war as morals.81 A nation that does not have sufficiently strong morals has a great chance of losing every war in advance’. Poland’s security in the 21st century depends on a skilful combination of cooperation with its allies and the development of its own defence potential. Regional stability, support for Ukraine, modernising the armed forces and strengthening international cooperation are the pillars of Poland’s future security policy. Poland must find its place in a new multipolar world, where the principle Si vis pacem, para bellum (If you want peace, prepare for war) is more relevant than ever.

No comments.