Political shifts and government majority in right-leaning France

Some key findings to keep in mind

The repeated surge of protest votes undermines our democracy

The RN’s progression is notable in the ballot box and in public opinion

If Marine Le Pen no longer generates a “republican front”, she still causes concern in a country that is in favour of Europe and the euro

In electoral terms, France is right-wing

Forming a government majority: Faced with the Nupes, who should be allied with whom?

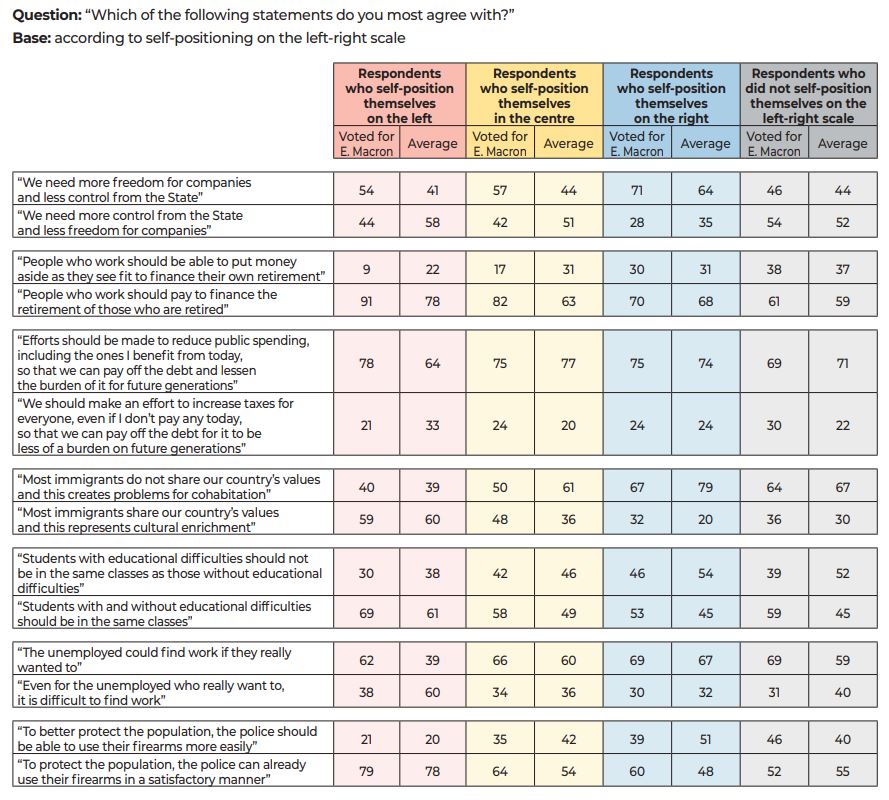

On key political issues, only LR and Ensemble! converge with the general opinion of voters

Introduction

A study on the 2022 electoral cycle by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

The repeated surge of protest votes undermines our democracy

In 2022, the majority of voters expressed some form of electoral protest

The spread of electoral protest is stronger on the right

Abstention from voting disguises a larger share of the vote for the Rassemblement national

The uncertain survival of mainstream political parties

The ballot box and public opinion: the dual victory of the Rassemblement national

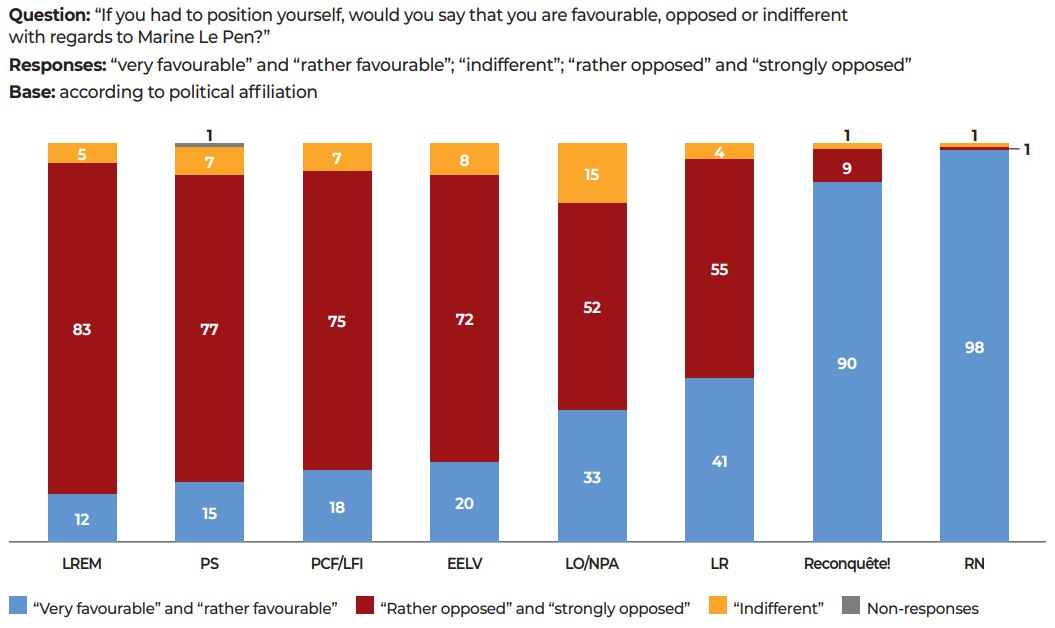

The growing acceptance of the Rassemblement national by the French public

An incomplete normalisation. Marine Le Pen attracts more support than the Rassemblement national

In right-wing France, the dilemma of Les Républicains: Joining forces with Ensemble! or with the Rassemblement national?

In 2022, two thirds of Emmanuel Macron’s voters can be classified as right-wing

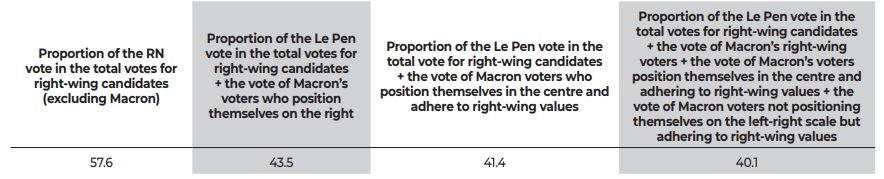

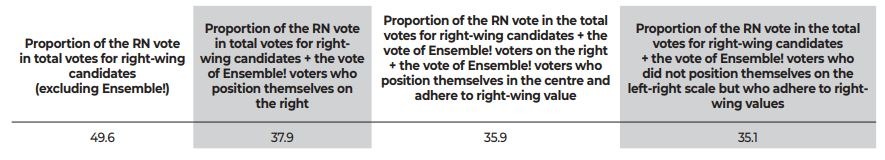

The Rassemblement national vote represents between a third and a half of the right-wing vote

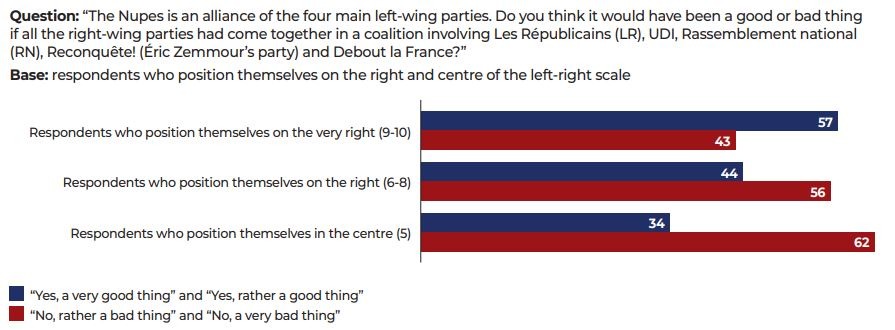

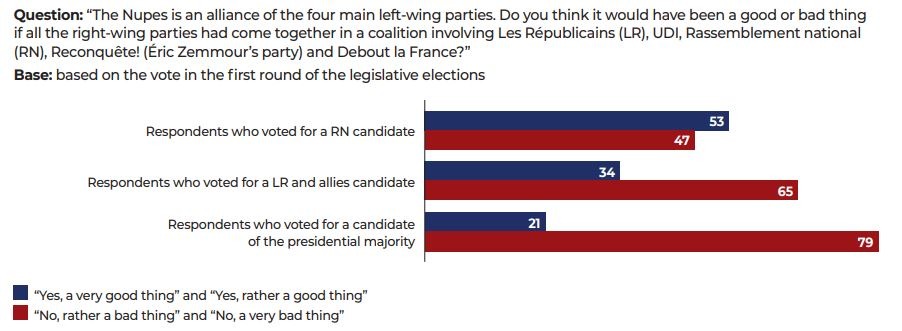

Should we form an alliance with the right? And if so, with whom?

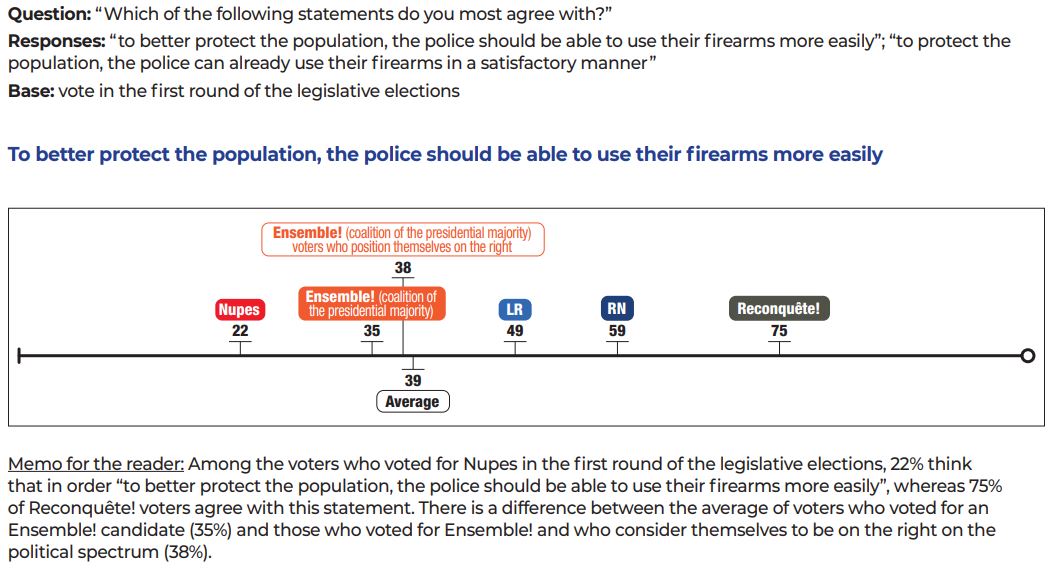

On key political issues, only Les Républicains and Ensemble! converge with the general opinion of voters

Conclusion

Summary

Combining abstention from voting, the so-called “blank vote” and anti-system votes (LFI, RN…), electoral protest has entered a new phase in the aftermath of the presidential and legislative elections of 2022. The success of Marine Le Pen and the RN have become more noticeable. As we show, this success is evident not only by the results of the presidential and legislative elections, but also in public opinion: there is a greater acceptance of the RN’s ideas. The surge in electoral protest has resulted in a further decline of the mainstream political parties. The mainstream parties both on the left, the Socialist Party (PS), and of the right, the Republicans (LR), are suffering an even greater decline than in 2017, in a more anti-system and right-wing France. Both the PS and the LR are threatened with marginalisation. One new element in 2022, during the legislative elections, is the presidential coalition (Ensemble!) that suffered a limited but real electoral setback in view of the clear re-election of Emmanuel Macron.

The political picture in France today is worrisome for the parties deemed capable of governing. The PS and LR no longer have the means to rely on their own forces nor to be the driving force behind a government alliance. Macronism, for its part, is being pushed to transform itself, both by this new environment and as a result of the effects of being institutionally constrained by Emmanuel Macron’s final term.

The continued weakening of our party system undermines our ability to govern, even as times are filled with immense challenges. There is, however, a window of opportunity as populist parties are also facing difficulties that are hidden by their admittedly impressive electoral results. This study from the Fondation pour l’innovation politique focuses on the results of the 2022 presidential and legislative elections, the two elections combined forming a complete “electoral cycle”. The opinion data were produced by a series of three successive surveys, initiated and carried out within the framework of a partnership between the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, the Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po (Cevipof) and the Centre d’études et de connaissances sur l’opinion publique (Cecop). The first survey was conducted in the days following the first round of the presidential election, to a sample of 3,005 people. The second survey was conducted in the days following the second round of the presidential election, to a sample of 3,052 people. Lastly, the third survey was conducted in the days following the second round of the legislative elections, to a sample of 3,053 people. The three waves of this survey were conducted by the OpinionWay Institute.

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

2022 the Populist Risk in France - Wave 5

2022, French presidential election impacted by crises

Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

What next for democracy?

Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Victor DELAGE, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE

Victor DELAGE, Anne FORNACCIARI, Nicola GADDONI, Katherine HAMILTON, Apolline MOURIER, Dominique REYNIÉ, Axel ROBIN, Clémentine SCOTTO, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE

Alexandre AGACHE, Victor DELAGE, Anne FLAMBERT, Anne FORNACCIARI, Nicola GADDONI, Katherine HAMILTON, Apolline MOURIER, Axel ROBIN, Clémentine SCOTTO, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE

Alice CANDY

Katherine HAMILTON

Julien RÉMY

the Fondation pour l’innovation politique,

the Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po (Cevipof)

and the Centre d’études et de connaissances sur l’opinion publique (Cecop)

Opinion way

Laurent GASSIE (Customer Relationship Manager) Guillaume INIGO (Director of Studies)

Bruno JEANBART (Vice President)

Clément ROYAUX (Project Manager)

September 2022

Some key findings to keep in mind

The repeated surge of protest votes undermines our democracy

The blank vote consists of a voter placing either a blank ballot paper without any candidate’s name or an empty envelope in the ballot box, or ruining the ballot paper.

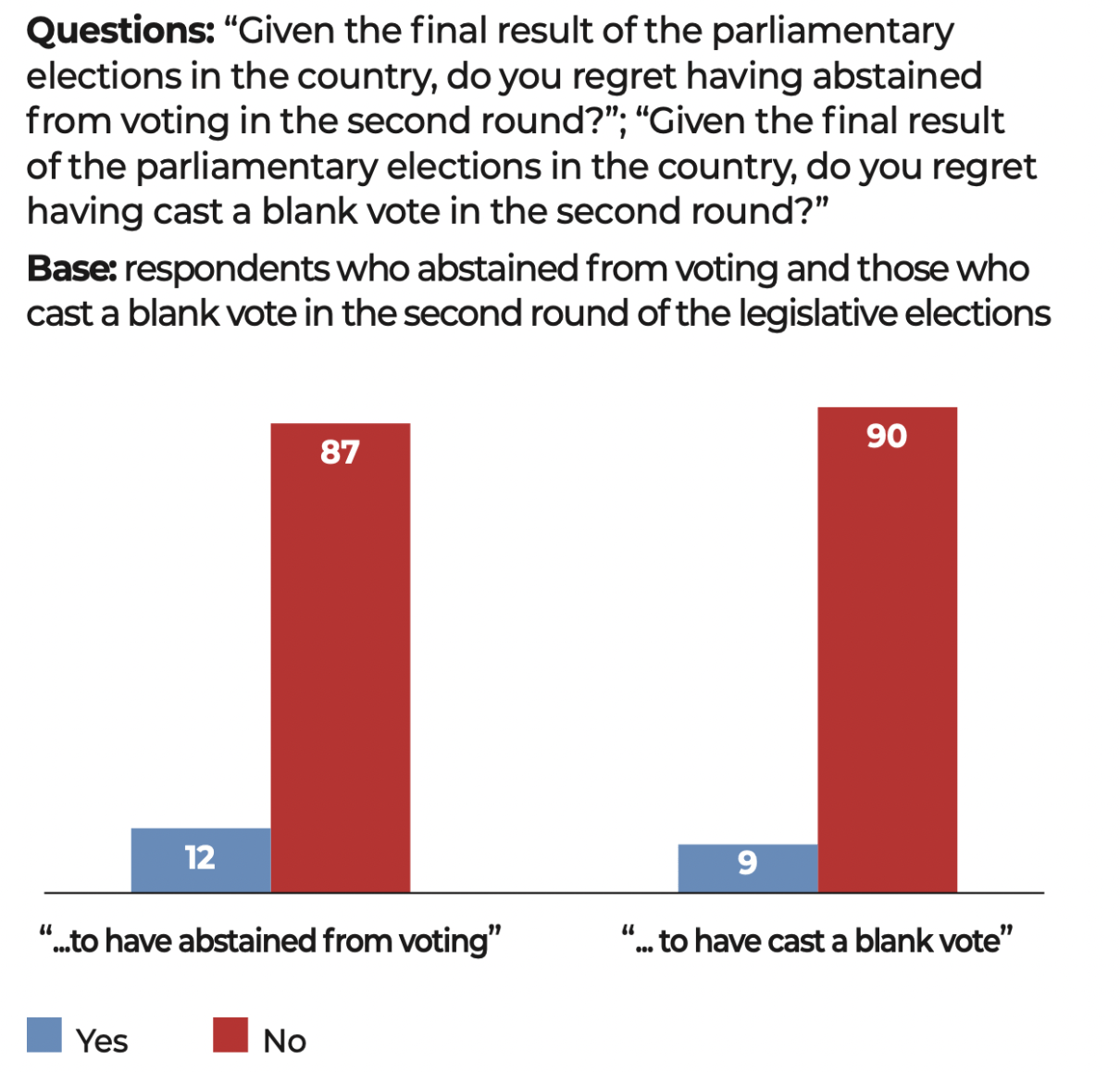

1. If we consider the votes cast in favour of a protest party, abstention from voting or blank votes1 during the legislative elections, more than three quarters of the registered voters were involved in electoral protest: 76.9% for the first round and 77.3% for the second round. We show that 87% of voters who abstained from voting in the second round do not regret it.

2. In twenty years, the total number of votes cast for protest candidates in the presidential election increased from 29.6% on 21 April 2002 to 55.6% on 10 April 2022.

3. The survival of mainstream political parties is at stake. In the first round of the presidential election, on 10 April 2022, the protest votes (in favour of Marine Le Pen, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Éric Zemmour, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, Philippe Poutou, and Nathalie Arthaud) accounted for a majority (55.6%) for the first time in our electoral history. In the first round of the legislative elections on 12 June 2022, the protest vote (in favour of the Nupes, the Rassemblement national (RN), Reconquête!, various extreme left-wing parties, sovereigntist right-wingers, the radical left party (PRG), and other various extreme right-wing parties) also represented a majority of voters (50.9%).

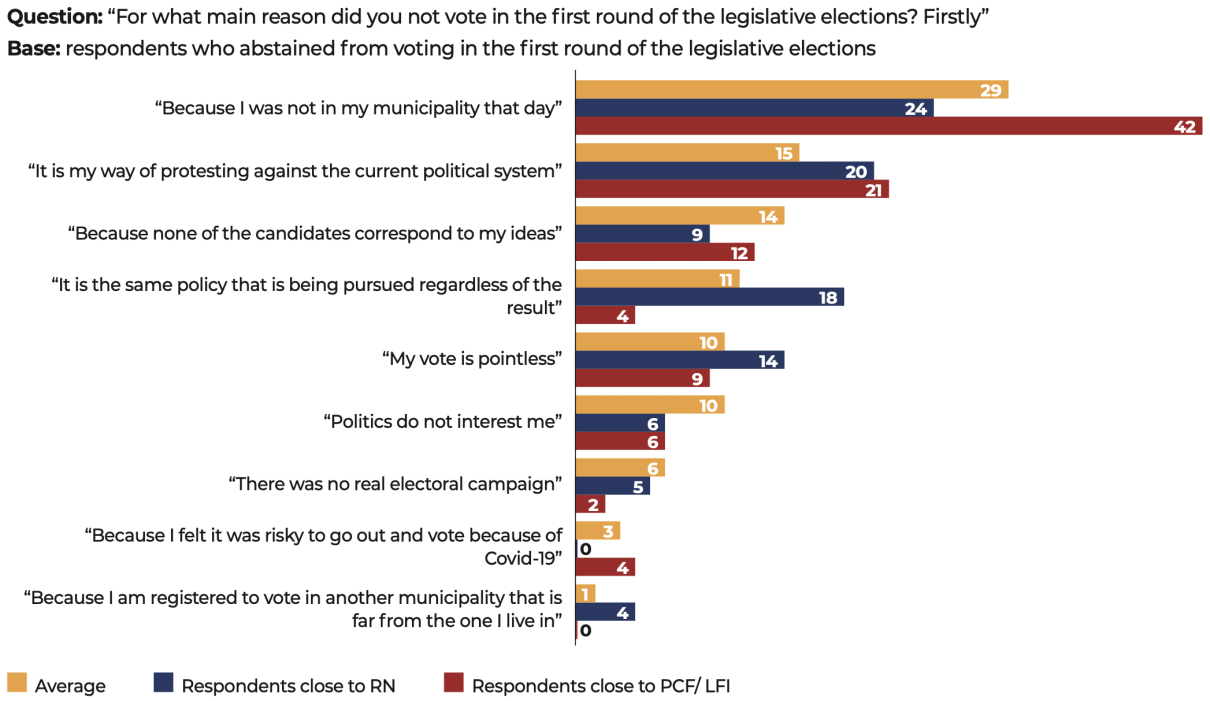

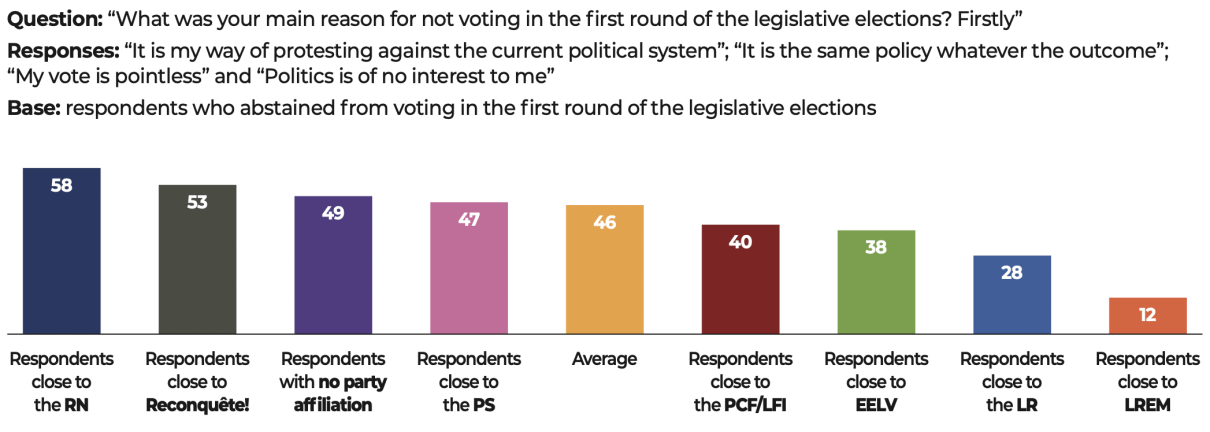

4. In a major upset, the RN became the first opposition group in the National Assembly. However, only 55% of Marine Le Pen’s voters in the first round of the presidential election voted in the first round of the legislative elections. The abstention f rom voting disguises a larger share of the vote for the RN. In fact, 58% of voters close to the RN who abstained from voting justify this abstention with a protest motive, against 46% of abstainers on average and 40% of abstainers close to the French Communist Party (PCF) or the France insoumise (LFI).

The RN’s progression is notable in the ballot box and in public opinion

1. In the 2017 presidential election, the total protest vote amounted to 21.3% for the left-wing candidates (Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Philippe Poutou and Nathalie Arthaud); whilst the total for the right-wing candidates reached 27.1% (Marine Le Pen, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, François Asselineau and Jacques Cheminade). In the 2022 presidential election, the right-wing protest vote accounted for 32.3% of the votes cast (Marine Le Pen, Éric Zemmour and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan), compared with 23.3% for the left-wing protest vote (Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Philippe Poutou and Nathalie Arthaud). Between 2017 and 2022, the protest vote in the presidential election is dominated by the right, while increasing more strongly on the right (+5.2 points) than on the left (+2 points).

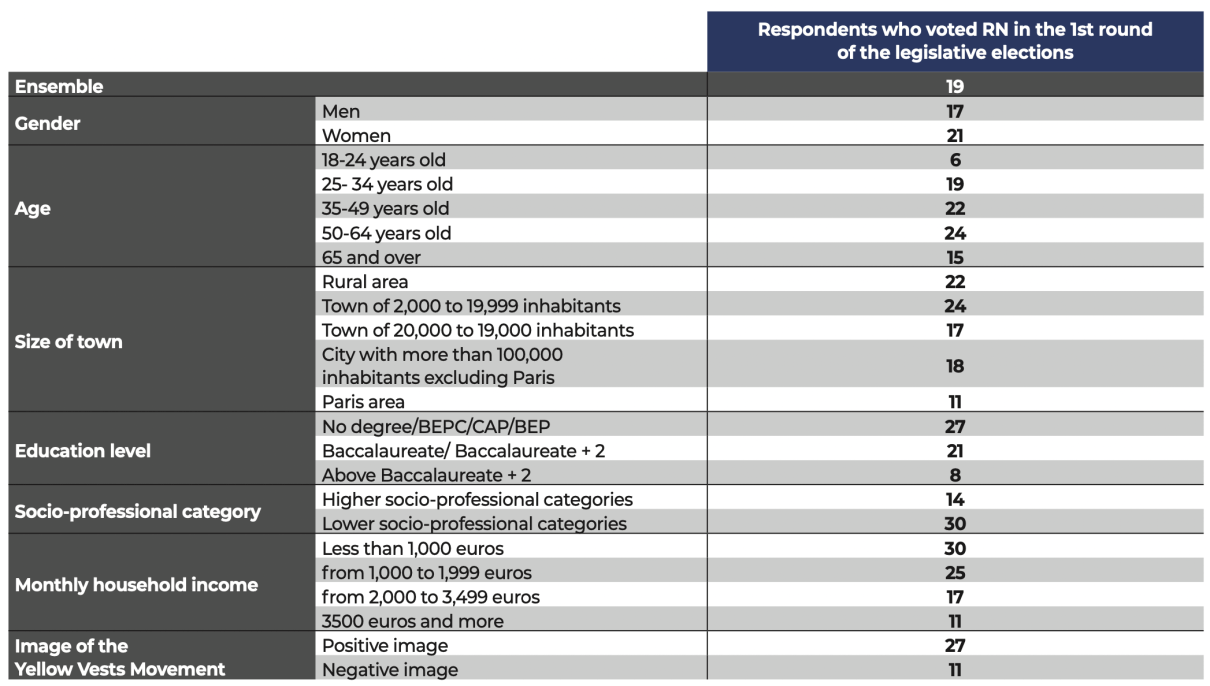

2. As it grows, the RN’s electorate is diversifying. It is growing in towns with more than 100,000 inhabitants (excluding Paris), where its share (18%) in the first round of the legislative elections is the same as the national average (19%). The RN vote is growing in the upper social categories: between the first round of the 2017 parliamentary elections and the 2022 parliamentary elections, the RN (or previously Front National) vote among white-collar workers has risen from 5% to 13%, and the vote among those with intermediate professions rose from 11% to 16%.

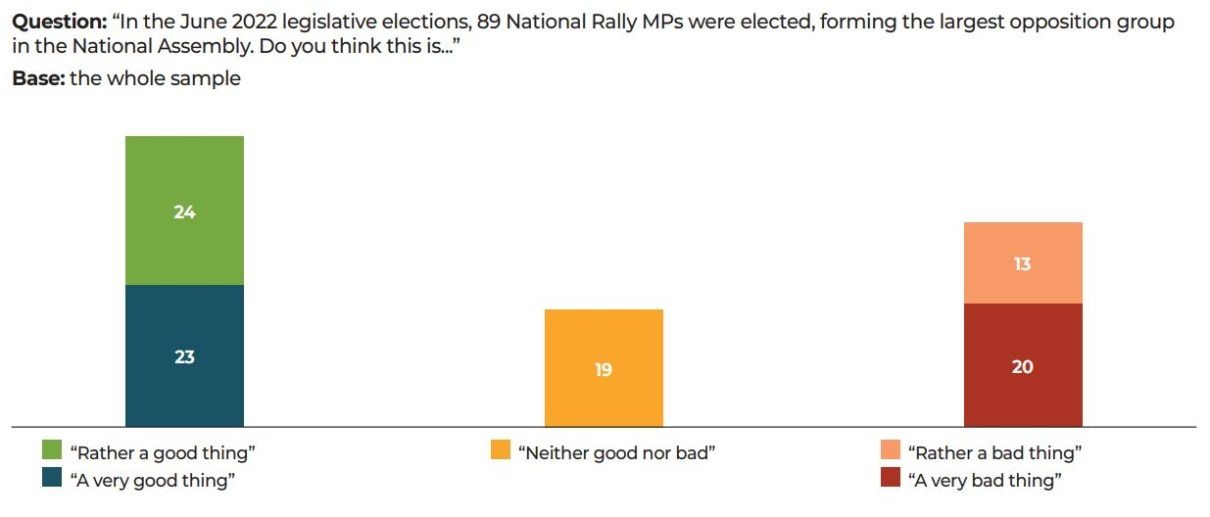

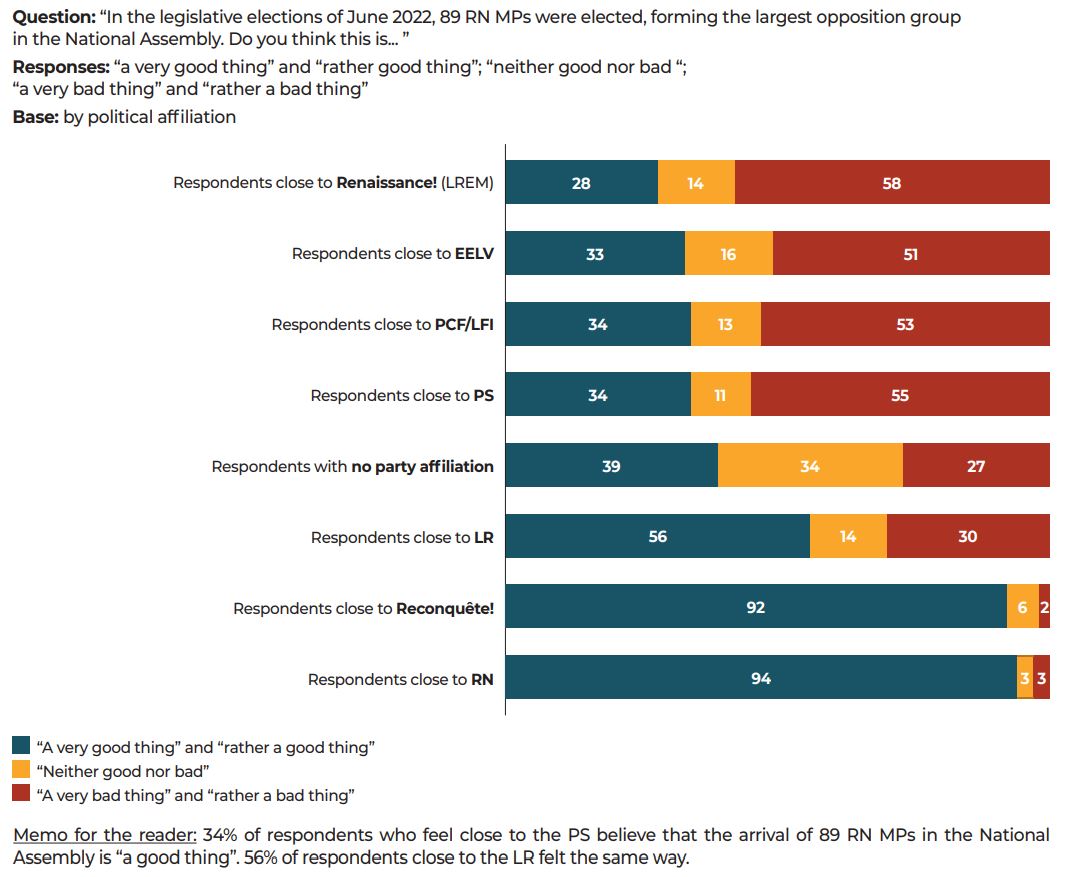

3. Almost half of voters (47%) see it as “a good thing” that “in the June 2022 legislative elections, 89 RN MPs were elected, forming the largest opposition group in the National Assembly”. It is considered a “bad thing” for 33% of respondents and ”neither a good nor a bad thing” for 19%.

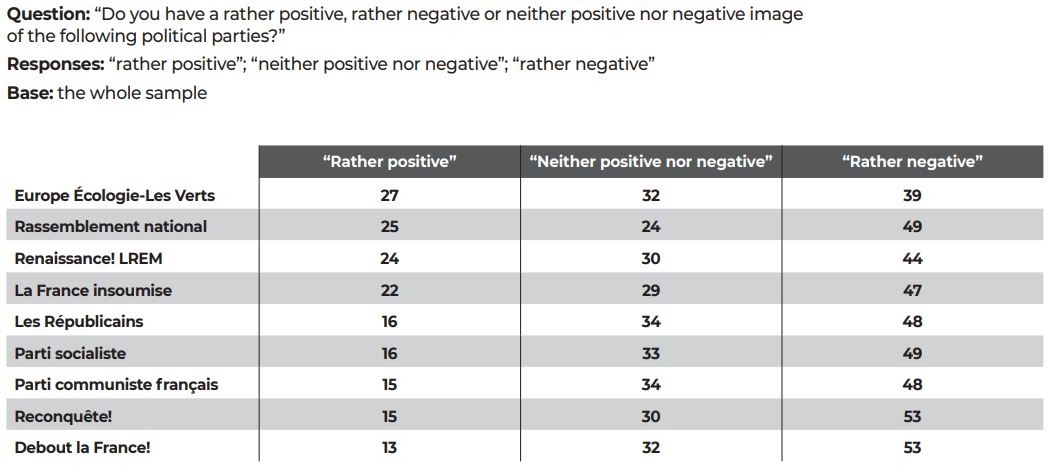

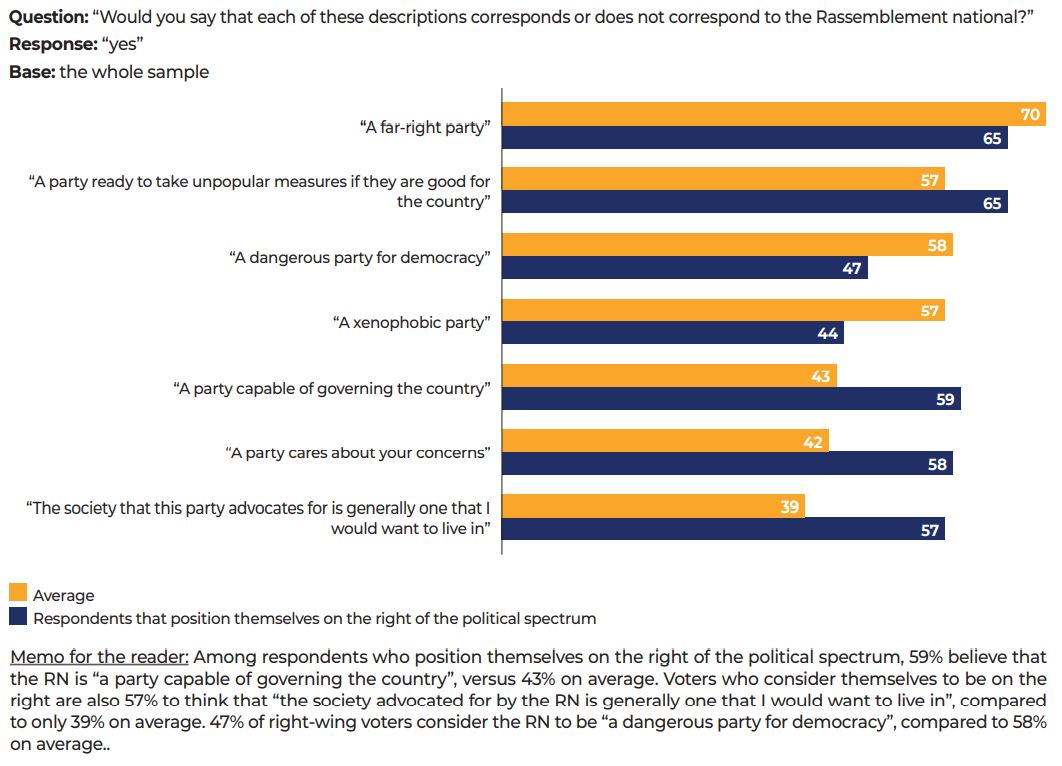

4. Less than half (47%) of right-wing voters consider the RN dangerous for democracy, while 44% consider it to be a xenophobic party.

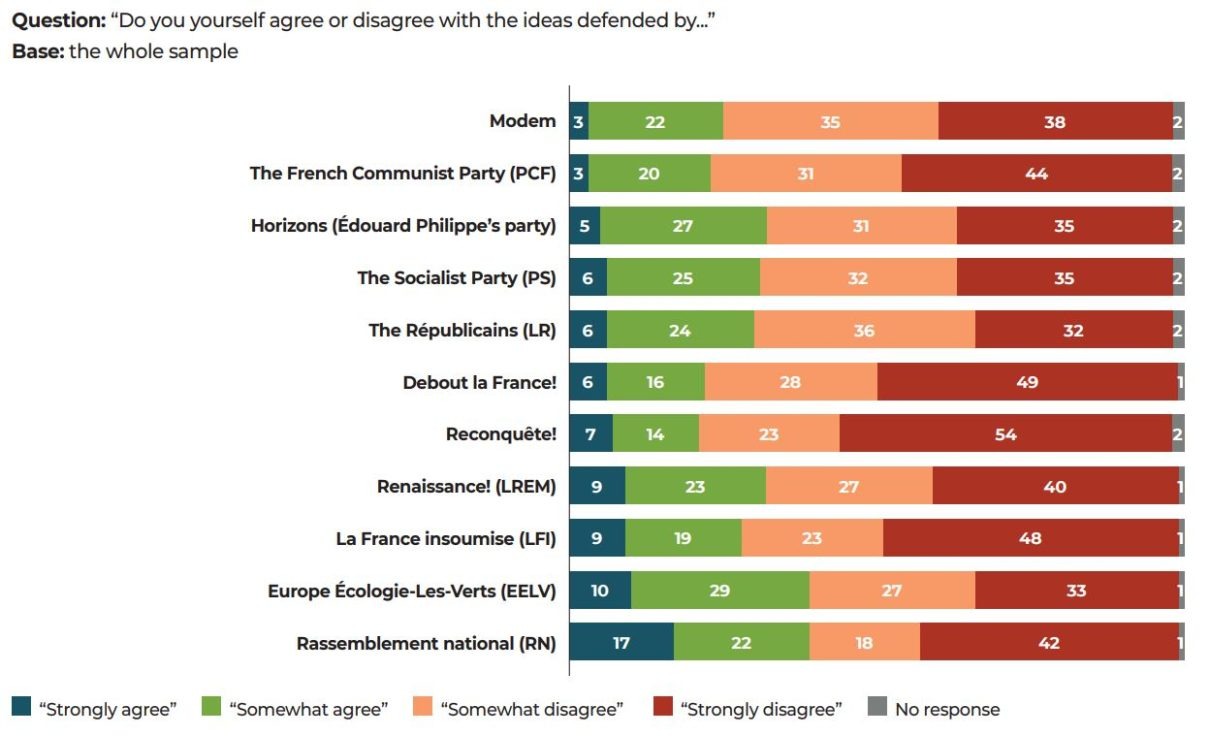

5. The RN’s ideas are supported both on the right and the left. Most of those close to Reconquête! (89%) agree with the RN’s ideas, as do half (47%) of those close to LR. But the RN’s ideas also find support among the left-wing electorate: 39% of those close to the Lutte Ouvrière (LO) or the Nouveau Parti Anti-capitaliste (NPA), 24% of those close to EELV, 22% of those close to the PCF-LFI, 17% of those close to the Socialist Party. Finally, 15% of those close to La Republique En Marche (LREM) and a third (32%) of respondents who are not close to any party identify with the RN’s ideas.

6. In public opinion, the RN has won the battle of populism: 39% of voters “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” with the ideas of the RN, while 28% of voters say they “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” with the ideas of LFI. Moreover, with 48% of voters who “strongly disagree” with the RN’s ideas, 28% say they “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” with LFI’s ideas. In addition, with 48% of voters “not at all in agreement” with its ideas, LFI is, after Reconquête! (54%) and Debout la France (49%), one of the three political formations whose ideas are most widely rejected.

7. EELV and the RN are the two parties whose ideas attract the most support. In both cases, 39% of respondents “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” with the ideas of the two parties. On the other hand, it is with the RN’s ideas that the greatest number of voters “strongly agree” (17%).

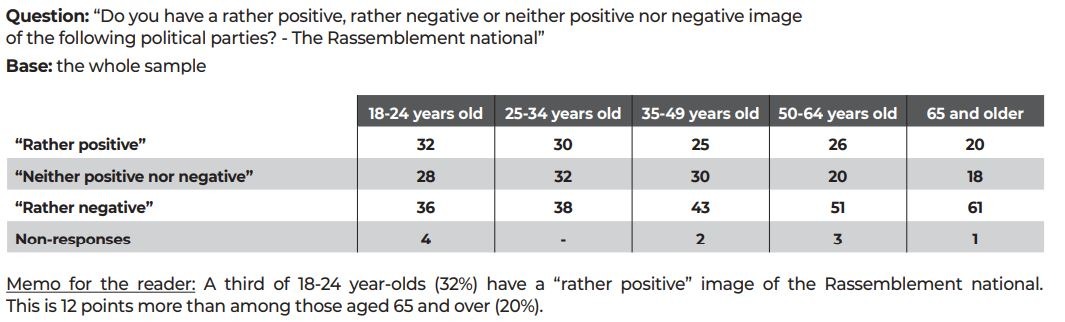

8. The age criterion does not significantly affect support for the RN’s ideas: 36% of 18-24 year-olds “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” with its ideas, 37% of 25-34 year-olds, 40% of 35-49 year-olds, 42% of 50-64 year-olds and 35% of those aged 65 and over.

9. Right-wing voters consider the RN capable of governing (59%). They also believe that it advocates for a society in which they would like to live (57%).

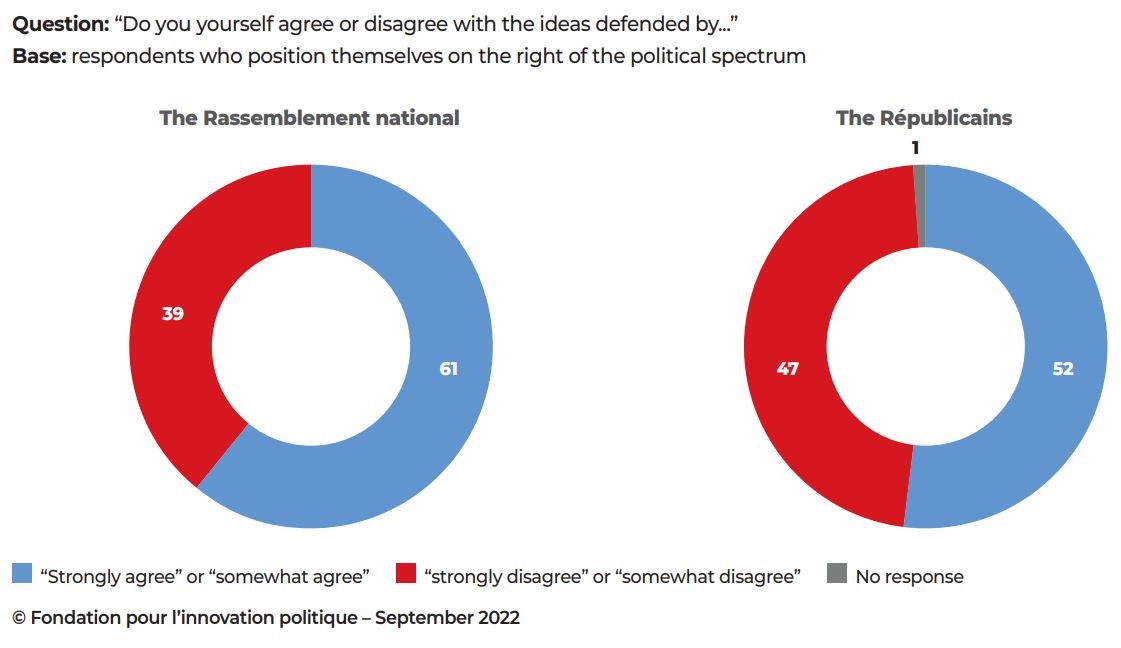

10. More right-wing voters agree with the RN’s ideas (61%) than with the LR’s ideas (52%).

11. In the first round of the 2022 legislative elections, the RN vote represented between a third and a half of the right-wing vote, depending on the criteria used (see below page 36).

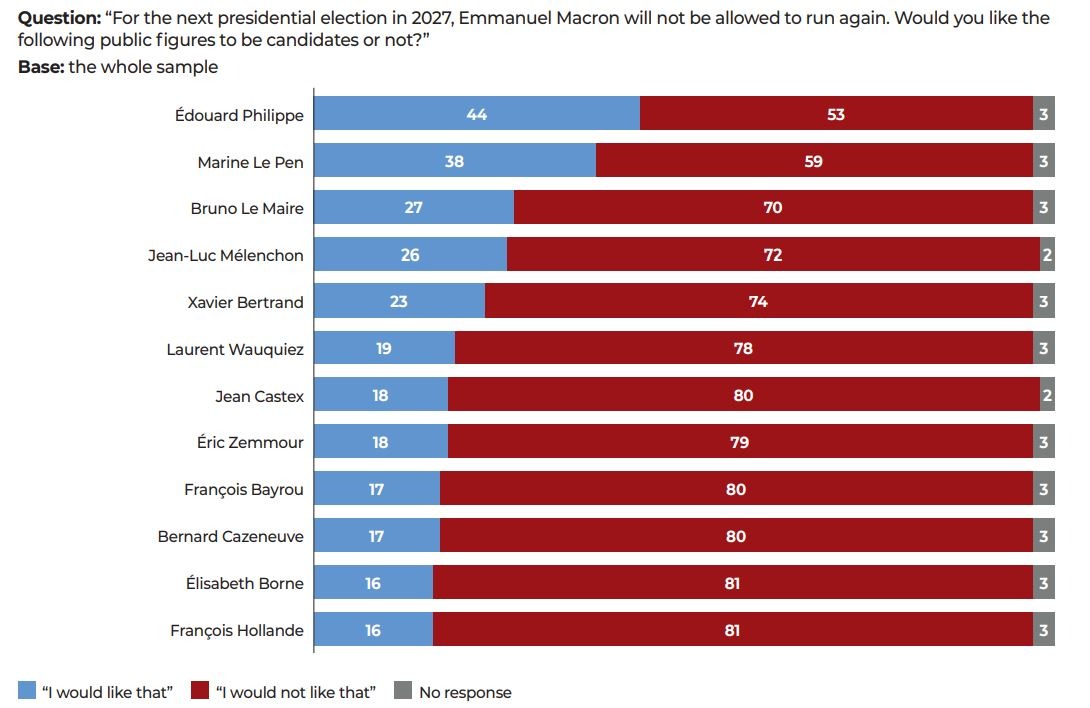

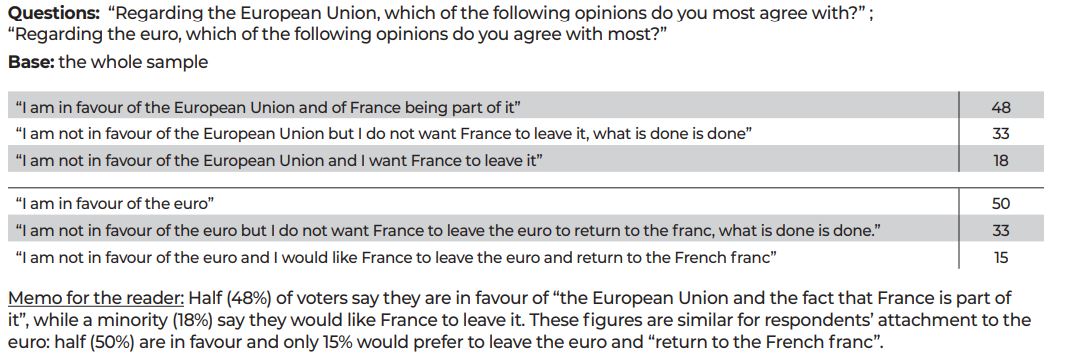

If Marine Le Pen no longer generates a “republican front”, she still causes concern in a country that is in favour of Europe and the euro

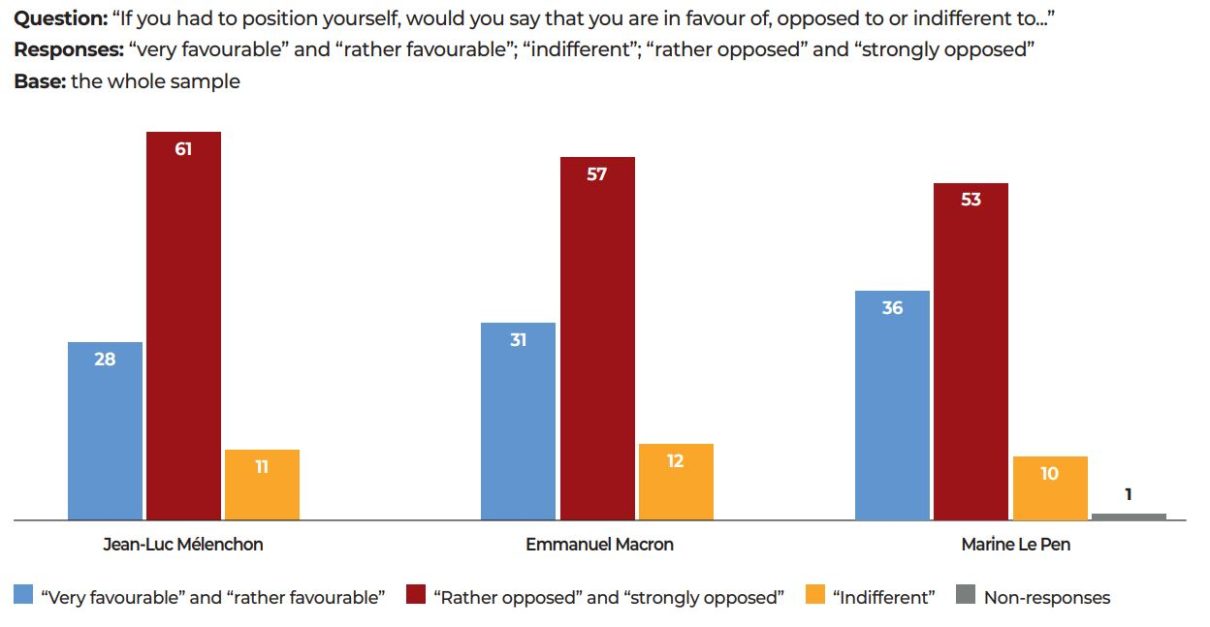

1. Out of the three main candidates in the presidential election, Emmanuel Macron, Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the RN candidate has the lowest level of rejection (53%) and the highest level of support (36%).

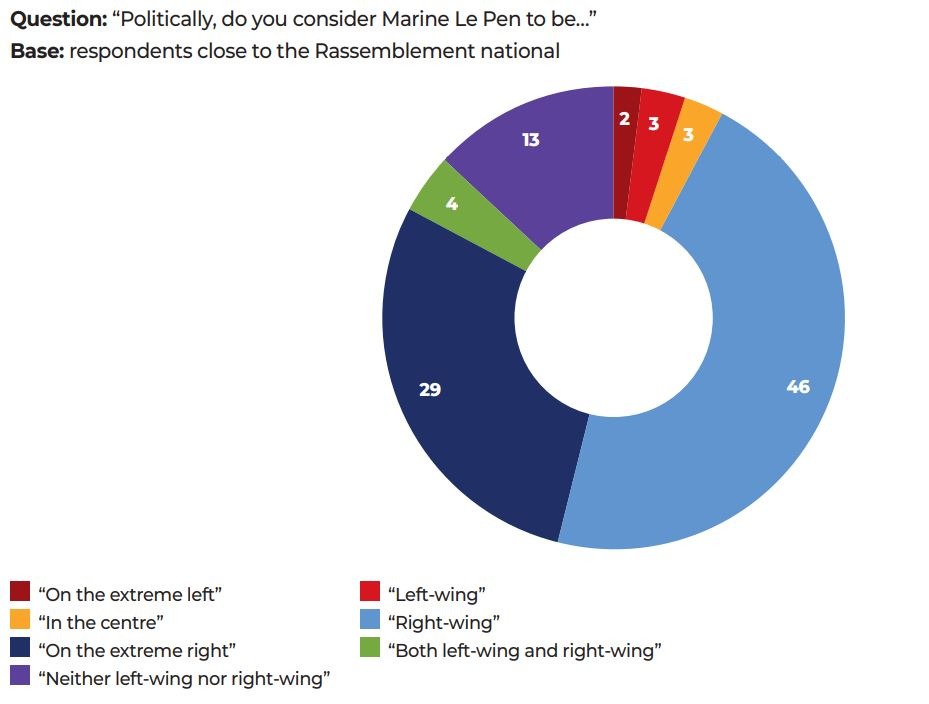

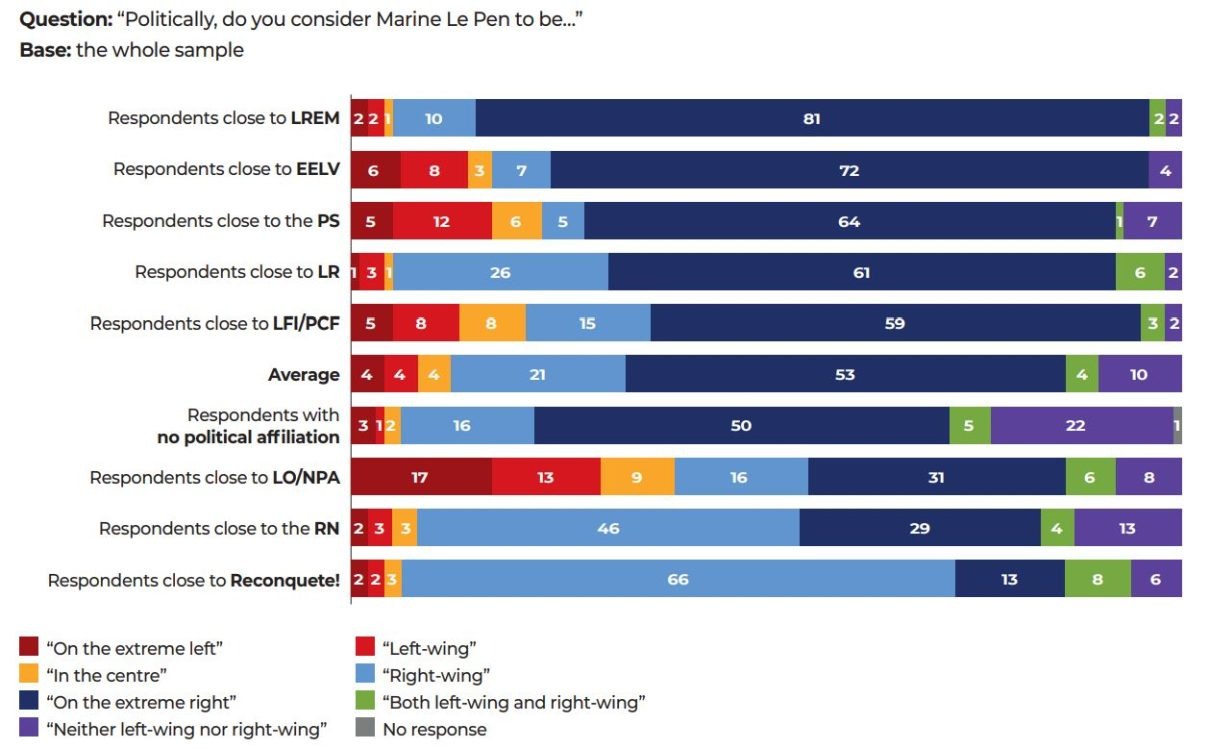

2. Most of the voters close to the RN (71%) do not classify Marine Le Pen as “far right”. This is also the case for those close to Reconquête! (87%) or LO-NPA (69%). Among the voters who still mostly place Marine Le Pen on the far right, there are significant variations between those close to the PCF-LFI (59%), the LR (61%), the PS (64%), EELV (72%) and LREM (81%).

3. A third of those close to LO-NPA (35%) and those close to PCF-LFI (34%) do not consider Marine Le Pen to be “worrisome”. Most of those close to LO-NPA (59%) and 35% of those close to PCF-LFI even agree with the idea that Marine Le Pen “has a good plan for the country”.

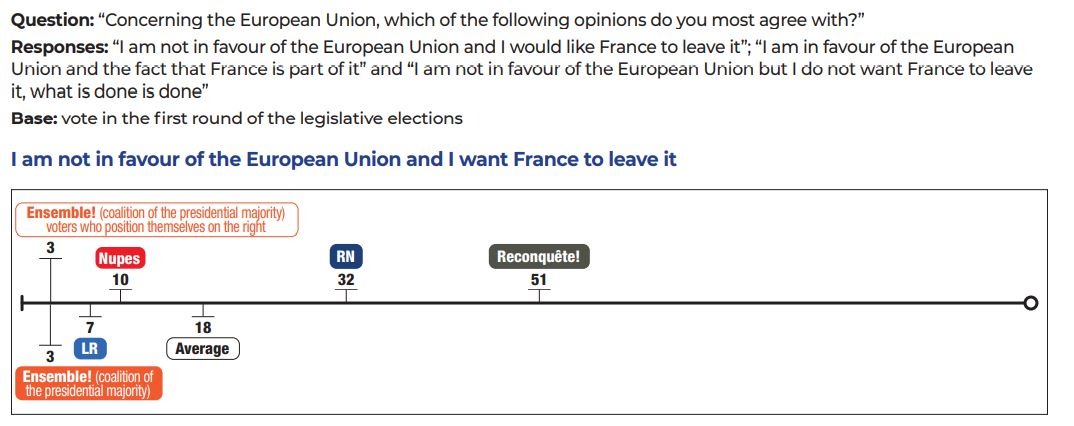

4. The RN candidate remains “worrisome” for 55% of respondents, with 54% believing that she would undermine fundamental freedoms if she became president of the French Republic, but the reservations about her are less political or moral than materialist and pragmatic. They are primarily based on the idea that her election would threaten the euro. Only a third (33%) of voters consider that, as president, Marine Le Pen would have been able to protect the euro, while 60% of voters credit Emmanuel Macron with this ability. The broad and constant support of the public for the European Union and, even more so, for its currency, is blocking the electoral expansion of the RN and countering the presidentialization of Marine Le Pen.

In electoral terms, France is right-wing

1. Emmanuel Macron’s electorate is on the right: half (47%) of Emmanuel Macron’s voters in the first round of the presidential election position themselves on the right of the political scale, 19% in the centre and 20% on the left. Finally, 12% did not position themselves on the political spectrum. We show that Macron’s voters who position themselves in the centre or who do not position themselves on the left-right axis are closer to the ideas of the right than the left.

2. Emmanuel Macron’s voters who position themselves on the right (47%), those who position themselves in the centre but who adhere to a right-wing value system (9.4%), those who do not position themselves on the political spectrum but who adhere to a right-wing value system (6.5%), lead us to estimate the proportion of right-wing voters in Emmanuel Macron’s electorate at 62.7%.

3. In the first round of the presidential election, the total votes obtained by Marine Le Pen, Éric Zemmour, Valérie Pécresse, Jean Lassalle and Nicolas Dupont- Aignan represented 40.2% of the votes cast. If we add Emmanuel Macron’s voters on the right, we reach 53.2%. With Emmanuel Macron’s voters who are in the centre but who express a right-wing value system, the total is 55.9%. Finally, with Emmanuel Macron’s voters who do not position themselves on the political spectrum but share right-wing values, the total is 57.7%.

4. If we compare with the results of the legislative elections, we observe that the right-wing parties (RN, Reconquête!, Debout la France, LR and their allies) obtained 37.7% of the votes cast. We reach 49.3% if we add the Ensemble! voters who position themselves on the right and 52% if we add the Ensemble! voters who are in the centre but whose value system places them on the right. Finally, with the Ensemble! voters who do not position themselves on the left-right axis but who share a right-wing value system, the total is 53.2%.

Forming a government majority: Faced with the Nupes, who should be allied with whom?

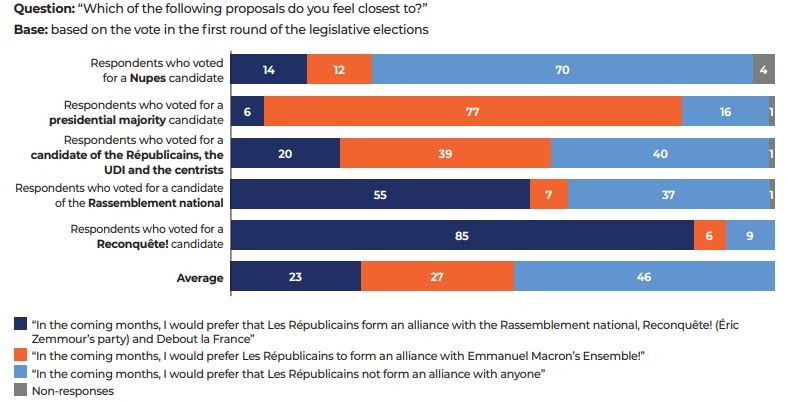

1. If we consider the entire electorate, half of the voters questioned (46%) do not want LR to form an alliance with another right-wing party; a quarter (27%) are in favour of an alliance of LR with Ensemble!; the remaining quarter (23%) want “LR to form an alliance with the RN, Reconquête! and Debout la France”.

2. If we consider right-wing voters, i.e. voters who position themselves on the right of the political spectrum, more of them (39%) would like an alliance between LR, RN, Debout la France and Reconquête! than an alliance between LR and Ensemble! (34%); finally, a quarter (26%) would prefer LR not to form an alliance at all.

3. If we consider LR voters in the legislative elections, the proportion of respondents wishing the party not to form an alliance (40%) is equivalent to the proportion favouring an alliance with the presidential coalition (39%). The hypothesis of an alliance associating all right-wing parties (LR-RN-DLF-Reconquête!) appeals to only 20% of LR voters.

4. Finally, three quarters (77%) of voters who voted for an Ensemble! candidate in the first round of the legislative elections would like to see an alliance between LR and the presidential majority. This result should be seen as a further indication of the right-wing orientation of Emmanuel Macron’s electorate.

5. The populist parties are facing difficulties that can be hidden by their successful electoral results. The question arises as to what will become of the RN without Marine Le Pen or LFI without Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Moreover, as things stand, neither LFI nor the RN will become forces of government if they are judged incapable of defending the European Union, in general, and the euro, in particular.

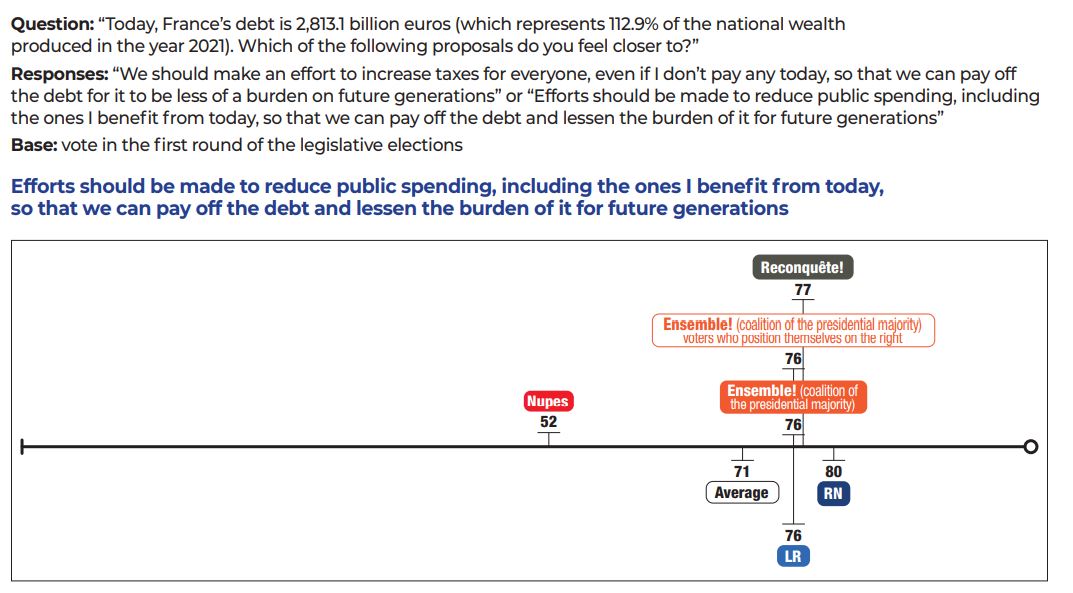

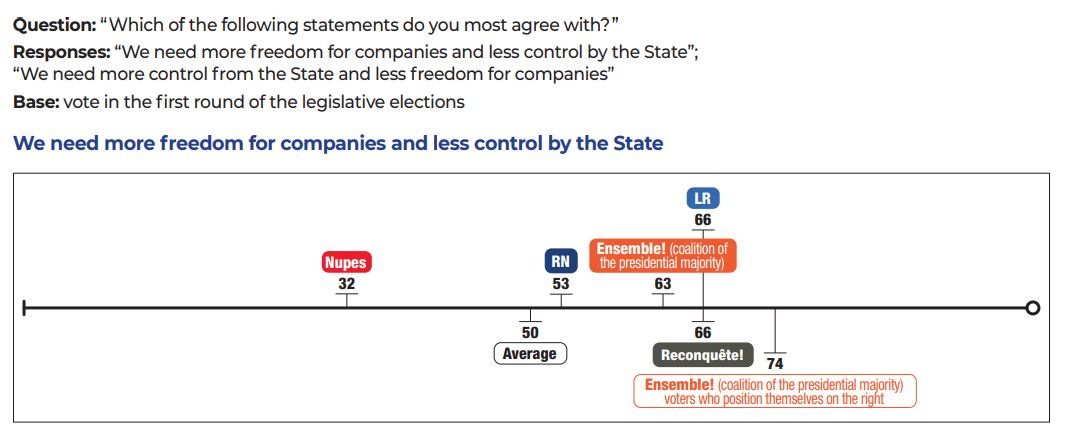

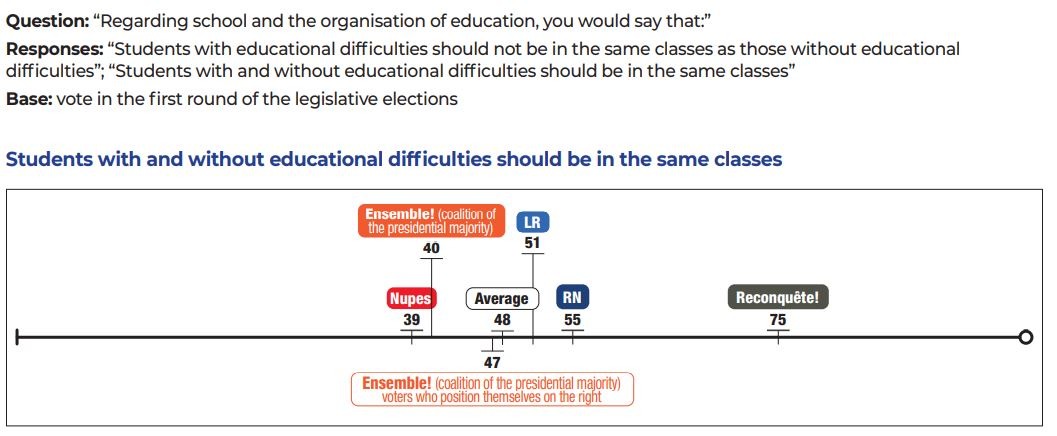

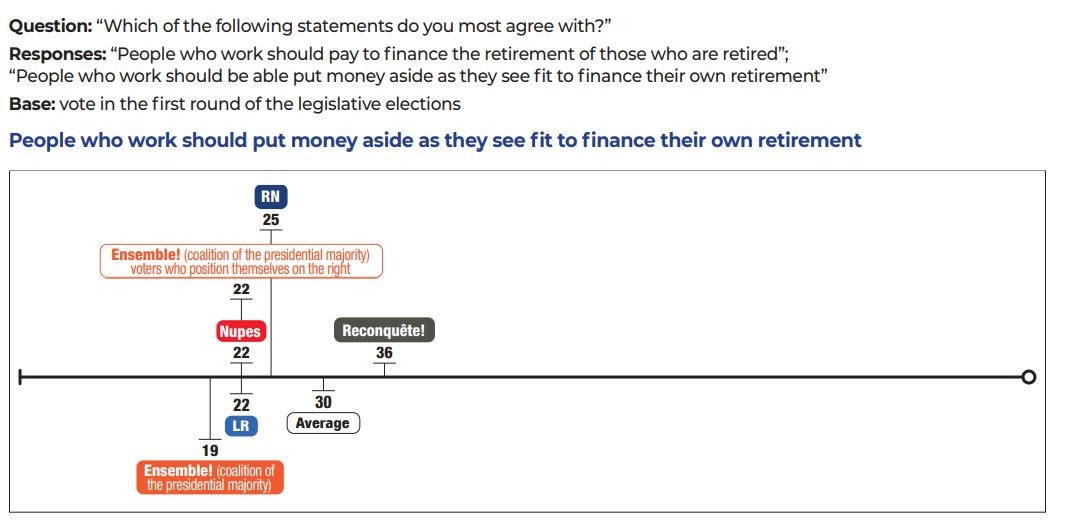

On key political issues, only LR and Ensemble! converge with the general opinion of voters

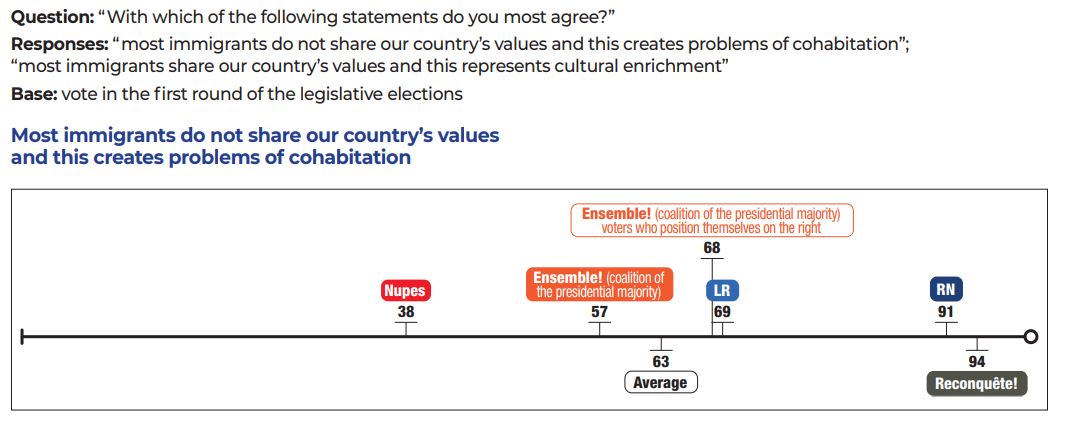

1. Immigration is a concern for public opinion: 63% of voters think that “most immigrants do not share the values of our country and this poses a challenge for coexistence”. This is the majority opinion among Ensemble! (57%), LR (69%), RN (91%) and Reconquête! (94%). On the other hand, this opinion is in the minority among Nupes voters (38%).

2. Symbolising a hardening of positions on immigration and integration issues, the fear of the “great replacement” theory is present in public opinion. Questioned in the days following the first round of the presidential election, almost half of voters (47%) said they shared the opinion that “populations of foreign origin will end up being the majority in France”. Among voters on the left, 27% share this opinion, compared with more than half of voters on the right (56%), but also those positioned in the centre (54%). 28% of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters in the first round of the presidential election fear the “great replacement” theory becoming a reality, as do a third of Emmanuel Macron’s (31%), Yannick Jadot’s (31%) and Fabien Roussel’s (31%) voters. Among voters of right-wing candidates, this opinion is predominant: it concerns 52% of Valérie Pécresse’s voters, 61% of Marine Le Pen’s voters and 83% of Éric Zemmour’s voters. This idea is also predominant among those who abstained from voting in the first round of the presidential election (58%).

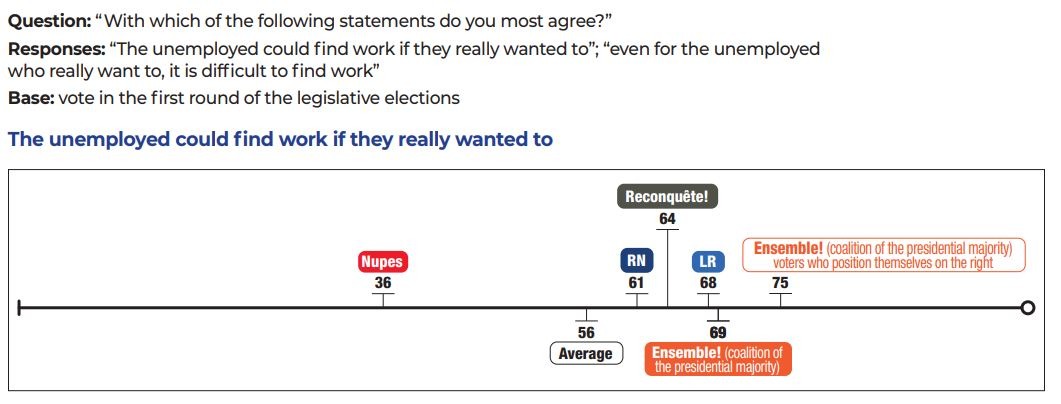

3. More than half (56%) of voters think that “unemployed people could find work if they really wanted to”. This opinion is held by a majority of RN (61%), Reconquête! (64%), LR (68%) and Ensemble! (69%) voters. This opinion is in the minority among Nupes voters (36%).

4. The opinion that “there should be more freedom for companies and less control by the state” is shared by 50% of voters. This was the majority opinion among RN voters (53%), as well as Ensemble! (63%), LR (66%) and Reconquête! (66%) voters. This a minority opinion among Nupes voters (32%).

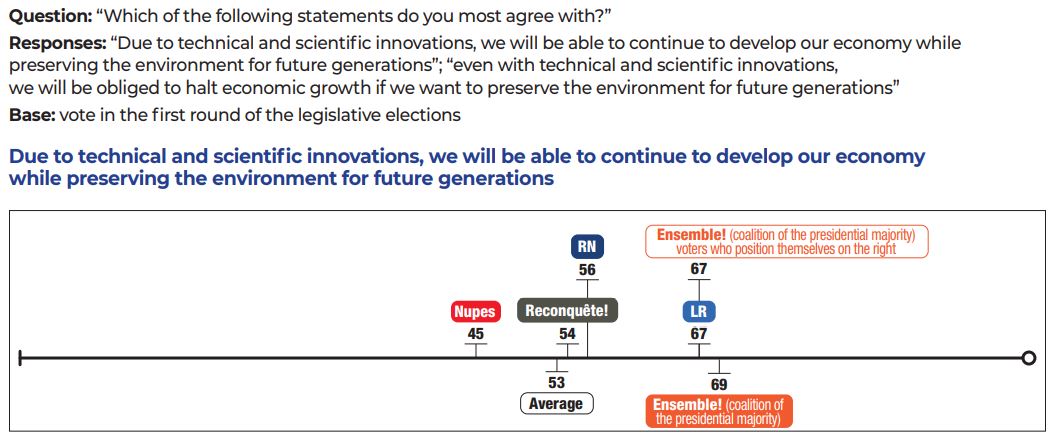

5. More than half (53%) of the voters believe that “thanks to technological and scientific innovations, we can continue to develop our economy while protecting the environment for future generations”. This opinion is held by a majority of Reconquête! (54%), RN (56%), LR (67%) and Ensemble! (69%) voters. This opinion is the least visible among Nupes voters (45%).

A study on the 2022 electoral cycle by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Although much more recent (2016), LFI, the party of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, will also face the typical challenge of founder-leader succession in populist political formations.

On 5 October 1972, Jean-Marie Le Pen founded the Front National (FN), on the far-right of the political spectrum. Chaired by Marine Le Pen since 2011, the FN became the Rassemblement national (RN) in 2018.

Combining abstention from voting, the so-called “blank vote” and anti-system votes, electoral protest has entered a new phase in the aftermath of the presidential and legislative elections of 2022. The mainstream political parties both on the left, the Socialist Party (PS), and of the right, the Republicans (LR), pillars of political and governmental life under the Fifth Republic of France, are threatened with marginalisation, although it should not be forgotten that they retain their power in the local authorities. Having been knocked out of the second round of the presidential election for the second time in a row, they are suffering an even greater decline than in 2017. However, in 2022, one element adds a cause for concern that did not exist in 2017. Indeed, in the legislative elections, Ensemble! the presidential coalition that emerged in the wake of Emmanuel Macron’s re-election, suffered a limited but real electoral setback. Although Emmanuel Macron was re-elected after an unprecedented term in office, the results of the legislative elections forced his government to negotiate a parliamentary majority, document by document, also a first.

The 2022 electoral cycle confirmed the rise in power of protest groups, dominated on the right by the Rassemblement national (RN) and on the left by La France insoumise (LFI). As in 2017, the presidential election saw Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon in a dominant position in opposition to the incumbent president. Unlike in 2017, not only did the populist vote not disappear in the legislative elections, but, and this is still unprecedented, the RN and LFI obtained the two largest parliamentary opposition groups. In one legislature, the total number of RN-LFI MPs increased f rom 25 to 164. The access of protest parties to parliament is in keeping with the order of the representative system.

However, the increase in the number of MPs from such political movements can make useful majorities costly or fragile, or even impossible to achieve, to the detriment of mainstream political parties.

At the end of Emmanuel Macron’s first five-year term, neither the PS nor LR managed to roll out a campaign able to bring back their former voters. However, the coming five-year term necessarily raises the question of how to recompose the party in a more urgent fashion. At least four political parameters will determine the direction of such a reconstruction. Firstly, in reality, there is only one major governing party – the presidential party. However, this party is under pressure from a scheduled decline, as Emmanuel Macron will not be able to serve a third consecutive term. Secondly, France is, in our view, predominantly right-wing, as we show below. This shift is favoured by the rallying of the governing left to the Nupes, a protest coalition initiated and led by LFI. Thirdly, the RN dominates the universe of right-wing parties. Fourthly, the RN is no longer the same party that has so agitated French political life since the 1980s, and that has so often harmed the right. Indeed, after having ditched the name chosen by Jean-Marie Le Pen, shifting from FN to RN, the party will soon be separated from the name of its founder, given that the presidency will not be held by a member of the Le Pen family. We know the role played by this form of authority – which combines personalization, genealogy and charisma – in the success of political organizations of this kind1. It is legitimate to ask how the fiftieth anniversary of the FN concerns the RN today2 or to what extent the old far-right party can still exist following such profound changes to its structure.

The context opened up by the 2017 presidential election called for a re-composition that did not take place. The 2022 electoral cycle made it more urgent. The meaning of this re-composition is the re-establishment of political forces whose views, although different and in competition with one another, do not prevent the sharing of a culture of government, allowing them to participate in the conduct of public affairs in a responsible and constructive manner.

An imperative re-composition, because we must remember that in the first round of the 2022 presidential election, the mainstream candidates, Emmanuel Macron, Valérie Pécresse and Anne Hidalgo, totalled 34.4% of the votes cast, or 24.8% of registered voters. The reconstruction of a governing democracy cannot afford to wait for the results of the next presidential election.

Methodology

This paper focuses on the results of the 2022 presidential and legislative elections, the two elections combined forming a complete “electoral cycle”. The opinion data were produced by a series of three successive surveys, initiated and carried out within the framework of a partnership between the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, the Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po (Cevipof) and the Centre d’études et de connaissances sur l’opinion publique (Cecop):

1. The first survey was conducted in the days following the first round of the presidential election, between 13 and 15 April 2022, among a sample of 3,005 people

2. The second survey was conducted in the days following the second round of the presidential election, between 28 April and 2 May 2022, to a sample of 3,052 people.

3. The third survey was conducted in the days following the second round of the legislative elections, between 23 June and 28 June 2022, with a sample of 3,053 people.

The three waves of this survey were conducted by the OpinionWay Institute. Each of these three opinion surveys was conducted among a sample of more than 3,000 people registered to vote and representative of the French population aged 18 and over. The representativenesss of the sample was ensured by the quota method, with regard to the criteria of gender, age, socio-professional category, category of urban area and region of residence.

The partnership made it possible to carry out these three surveys to better understand the logic and scope of two elections that probably mark a tipping point within a historical context.

The following study was written by the team of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique.

| Abbreviations of the different political parties used in this study DLF: Debout la France • EELV: Europe Écologie-Les Verts • FdG: Front de gauche FN: Front national • LCR: Ligue communiste révolutionnaire • LFI: La France insoumise • LO: Lutte ouvrière • LR: Les Républicains • LREM: La République en marche • NPA: Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste • Nupes: Nouvelle Union populaire écologique et sociale • PCF: Parti communiste français • PS: Parti socialiste • RN: Rassemblement national |

The repeated surge of protest votes undermines our democracy

For us, overall, the rise of electoral protest is beyond doubt. It has now even reached the parliamentary elections, which – with the exception of 1986 – it had hitherto spared. However, the scale of the protest was significantly smaller then, and part of the cause was a sudden change in the rules of the game when proportional representation was introduced. Though in 2022, the parliamentary elections were held under the majority system.

In 2022, the majority of voters expressed some form of electoral protest

Dominique Reynié (ed.), 2022, the Populist Risk in France, Wave 1, October 2019, 44 p.; Waves 2-3, October 2020, 86 p.; Wave 4, June 2021, 64 p.; Wave 5, October 2021, 72 p., Fondation pour l’innovation politique.

Dominique Reynié (dir.), 2022, French presidential election impacted by crises, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, April 2022, 84 p.

“La France insoumise, which initiated this regrouping of the left, represents the largest contingent of MPs (75). Twenty-nine seats are held by Socialist Party members, 23 by Europe Écologie-Les Verts and 12 by the Communist Party”, Matthieu Lasserre (with the AFP), La Croix, 21 June 2022.

See Rapport pour l’Assemblée nationale sur l’abstention. Mission d’information visant à identifier les ressorts de l’abstention et les mesures permettant de renforcer la participation électorale. Analyses et propositions (“Report for the National Assembly on abstention. Fact-finding mission to identify the causes of abstention and measures to increase voter turnout. Analysis and proposals”), November 2021, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 82 pages (report written at the request of the President of the National Assembly, Mr. Richard Ferrand).

It was a no-choice, no-threat election between two candidates of the moderate right, Georges Pompidou and Alain Poher. In the first round, the protest vote represented one-fifth of the votes cast, for Jacques Duclos, candidate of the PCF (21.3%), and Alain Krivine, candidate of the LCR (1.1%).

This counter-intuitive result is not necessarily paradoxical (see Dominique Reynié, “Le recours excessif à la dépense publique encourage l’agitation sociale”, L’Express, 13 June 2022).

Between 2019 and 2022, we published six studies dedicated to the rise of electoral protest in France. The first five studies focused on the Populist Risk in France3, and then, in April 2022, a complementary study was devoted to the French presidential election impacted by crises4. This research allowed us to measure electoral protest by asking voters about their willingness to engage in one of the following protest behaviours: abstention from voting, blank voting and votes for protest parties. In each of the six surveys, we recorded the rise in protest sentiment as defined by these three types of behaviour. The results of the presidential election confirmed the reality of this trend.

In line with the presidential election, the legislative elections of June 2022 were also marked by a strong increase in electoral protest. It should be noted here that in order to evaluate the level of protest in the context of these legislative elections, we are taking into account, in addition to abstention from voting and the blank vote, the votes in favour of the candidates of the Nupes, the various extreme left-wing parties, DLF, Reconquête! and the RN. Of course, not all the candidates presented by the Nupes were f rom the so-called “protest” group, but this was indeed the case, in our opinion, for the LFI candidates. The protest nature of the Nupes stems firstly f rom the dominant role played by Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s party in its constitution, which is reflected in retrospect by the election of many LFI MPs, who far outnumbered the other parties in the coalition5. In addition to this, there are the candidates’ of several other coalition parties, in particular EELV, and more broadly the parliamentary protest strategy accepted by the different components of Nupes. This leads us to include the totality of the votes in favour of the Nupes as part of the electoral protest, even if a minor proportion would not have been part of it in a different political configuration.

The same applies to those who abstain from voting. Even if interest in the legislative elections is generally lower than for the presidential election, abstention from voting in June 2022 is the result of a plurality of motives where the protest dimension is prevalent. We sought to better identify the motivations of those who abstain from voting: 15% of respondents told us that abstention from voting was their “way of protesting against the current political system”, 11% justified it by the fact that “the same policy is pursued regardless of the outcome, 10% replied because “my vote is pointless”, and 10% because “politics do not interest me”. The total of these justifications accounts for 46% of the reasons for not voting. Some people voted to express a form of spite or anger, while others were prevented from voting by practical or contingent reasons such as being away from their polling place on election day.

In the first round of the 2022 legislative elections, less than a third of those questioned (29%) said that their main reason for not voting was “because they were not in their municipality on election day”. Without going into too much detail, as we have developed this argument elsewhere6, it is difficult not to see the fact that nearly a third of those who abstained from voting justified themselves by invoking a distance from their polling station on election day as a form of civic disengagement, or even indifference, given that the importance of the presidential and legislative elections could have motivated them to use the proxy system (where you can ask someone close to you to vote for you in your absence). It is difficult to measure in more detail the reason for these votes or abstentions from voting. The fact remains that, in the history of the Fifth Republic, the increase in abstention from voting is accompanied by an increase in protest votes. In this context, abstention f rom voting fuels electoral protest.

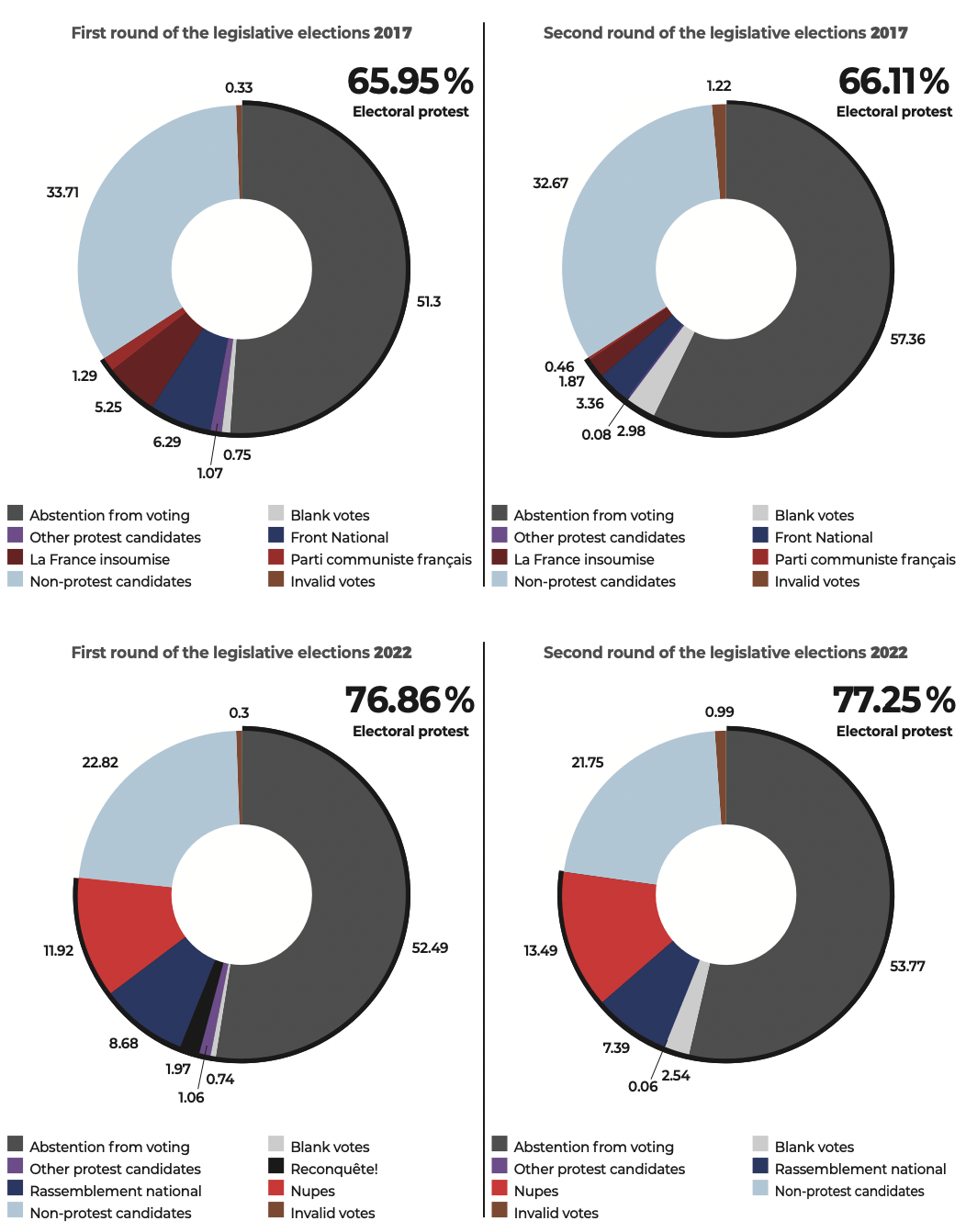

If we compare the results term by term, i.e. including abstention from voting, blank votes and votes for designated protest parties, electoral protest behaviour concerned most of the registered voters in the legislative elections: 76.9% for the first round and 77.3% for the second round, i.e. an increase of 11 points compared to the 2017 legislative elections, which were already a historic record (66% in the first round, 66.1% in the second round). The level of electoral protest thus defined may be slightly lower than these figures, due to the difficulty of knowing more precisely the motives behind these electoral choices. However, electoral protest is largely predominant and we can easily observe, term by term, that it has never been so widespread in our electoral history as in 2022.

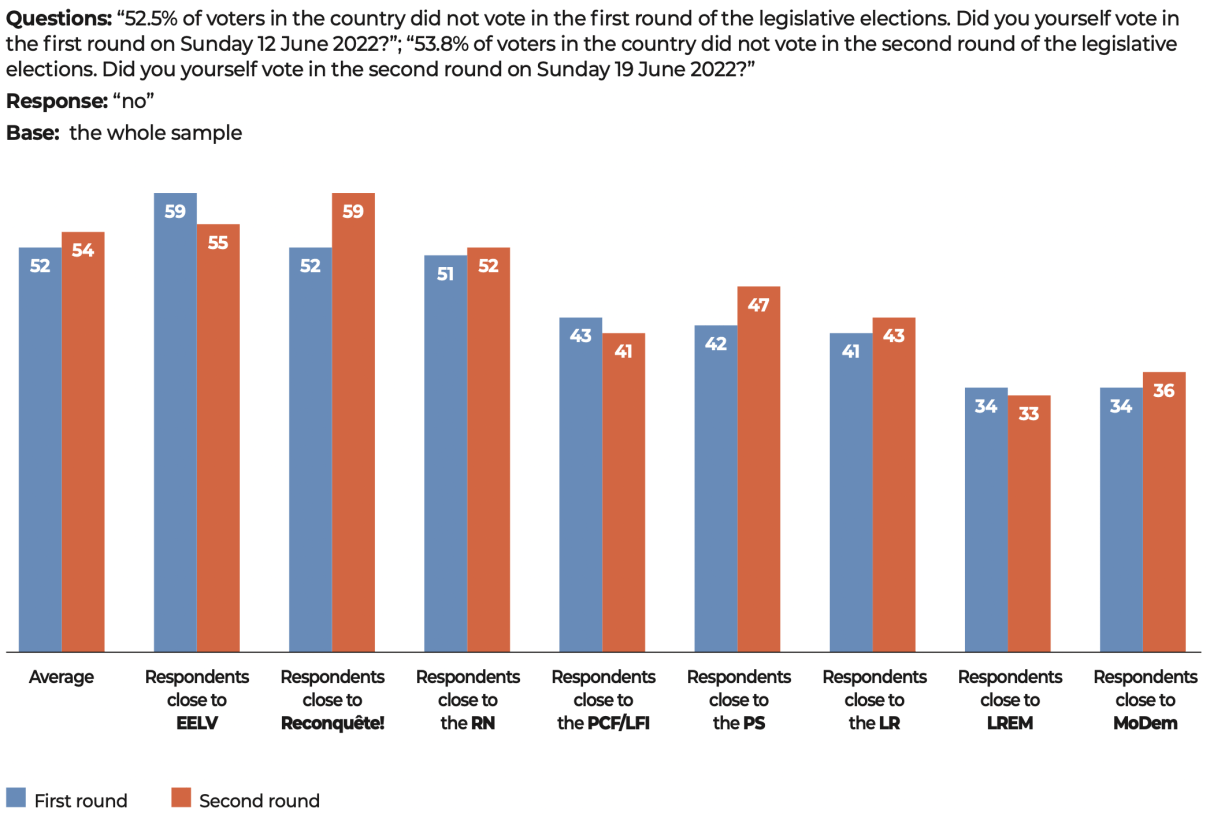

Massive abstention from voting has become a feature of our public life over the last ten years. In the legislative elections, the record high abstention rate for the second round was reached in June 2017 (57.4%). In 2022, for the second time in a row, more than one in two voters abstained, both in the first (52.5%) and the second rounds (53.8%).

Let it be stressed that the increase in abstention f rom voting has been a visible trend for several years. For the presidential election, the record for a first round was recorded on 21 April 2002 (28.4%). The 2022 presidential election has the second highest abstention rate (26.3%). The second round of the 2022 presidential election also holds the second highest figure (28%), the previous record (31.1%, in 1969) being in a very different context7. For municipal elections, which are the other preferred election of the French, together with the presidential election, the record for the second round is 28 June 2020 (58.4%).

The pandemic, including its effects on the first round, does not account for everything. Indeed, the end of lockdown had been announced on 7 May and initiated on 11 May. When the second round took place, most of the French population were able to move around and lived more or less normally for a month and a half. Above all, abstention from voting in the 2020 municipal elections confirms a pre-pandemic trend. The previous record for the first round of municipal elections dates back to March 2014 (36.5%). The same is true for the regional and departmental elections in June 2021. Even though they have, by nature, less turn-out than municipal and national elections, the 2021 departmental and regional elections had spectacularly low turn-out rates (66.7% in the first round).

Abstention from voting strongly affects all our elections. It does not have the same impact depending on the nature of the election and the candidates and parties, but it is undoubtedly a powerful factor in the disintegration of the French political landscape. Abstention from voting acts as a disorientated force. It is not driven by any intention, so it produces effects that may surprise even those who abstained from voting, despite the fact that they tend to not regret their behaviour.

This new surge in electoral protest is all the more spectacular because it takes place in the context of a welfare state that is now more generous, or more spendthrift, than ever. Indeed, faced with the consequences of the unprecedented Covid-19 pandemic, the state has not hesitated to borrow and mobilise considerable sums of money to support these lockdowns, finance massive testing services and vaccination campaigns, support households, businesses or professions deemed most affected by the health crisis, etc. However, the deployment of these colossal public resources, unparalleled in any other democracy, did not prevent a widespread lack of interest in public affairs, as measured by the increase in voter abstention and, at the same time, a propensity to vote for anti-system candidates8. This is illustrated by the scores obtained by the populist candidates in the first round of the presidential election (55.6%), whose total exceeded the majority of votes cast for the first time.

Those who abstained from voting and those who cast a blank vote do not regret it

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

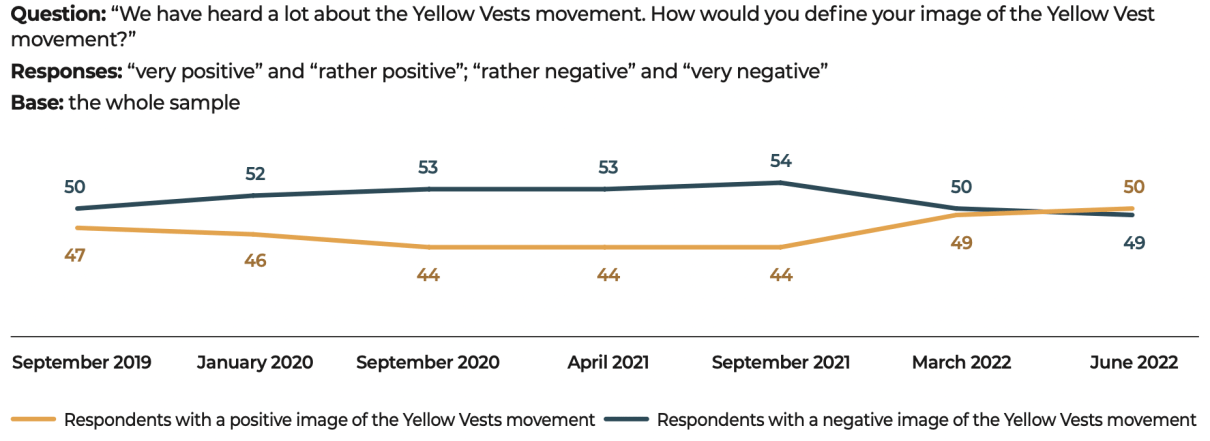

Half of French people have a “positive image” of the Yellow Vest movement

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Electoral protest in the 2017 and 2022 legislative elections

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Source :

The spread of electoral protest is stronger on the right

On the subject, cf. Luc Rouban, La Mutation du Rassemblement national, Cevipof, July 2022, 7 pages.

See Abdelkarim Amengay, Anja Durovic, and Nonna Mayer, “L’impact du genre sur le vote Marine Le Pen”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 67, no. 6, December 2017, pp. 1067-1087.

In the first round of the 2017 presidential election, the total protest vote amounted to 21.3% for left-wing candidates (Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Philippe Poutou and Nathalie Arthaud); the total for the right-wing candidates reached 27.1% (Marine Le Pen, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, François Asselineau and Jacques Cheminade). In the first round of the 2022 presidential election, the right-wing protest vote accounted for 32.3% of the votes cast (Marine Le Pen, Éric Zemmour and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan), compared with 23.3% for the left-wing protest vote (Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Philippe Poutou and Nathalie Arthaud). Between 2017 and 2022, the protest vote in the first round of the presidential election was dominated by the right, while growing faster on the right (5.2 points) than on the left (2 points). Furthermore, in the first round of the legislative elections, the FN/RN vote rose from 13.2% of the votes cast in 2017 to 18.7% in 2022. The analysis of the results shows that the RN remains, in sociological terms, the most popular party. As in the FN’s time, RN voters are less educated and more likely to live in small and medium-sized towns. However, as the RN electorate has grown in number, it has become more sociologically diverse, drawing in profiles that were not previously represented.

Thus, outside the Paris area, where the RN vote remains lower (11%) than the national average, it is strongly increasing in towns of more than 100,000 inhabitants, where a fifth (18%) of voters gave their support to a RN candidate, a similar percentage to the national average (19%). Similarly, the findings also confirm the existence of an electoral base that is now predominantly female. This is one of the impacts of the arrival of Marine Le Pen at the head of the party. The sociology of the FN/ RN vote underlines the historical failure of mainstream political parties, whether on the left or the right, among the working classes.

On the other hand, like all parties, the RN is struggling to mobilise young voters. This is a general weakness. The younger the voter, the less likely he or she is to participate in any election. The socio-demographic data collected therefore concerns a minority of young people, those who actually voted, i.e. only about a third of the age group considered. In addition, for most voters under the Fifth Republic, dominated by the culture of the presidential election, legislative elections are both less clear and less mobilising than the latter. Thus, in 2022, almost two-thirds (62%) of 18–24-year-olds did not participate in the first round of the legislative elections. Social stature combined with the effect of age means that, sociologically, the lower class an electorate is, the more likely it is to abstain from voting, especially in legislative elections, and even more so among the younger generations.

The RN’s score among young voters who took part in the legislative elections is the consequence of this triple constraint. The RN’s low score (6%) among 18–24-year-olds must be assessed in the light of the proportion of young voters, who are socially more affluent and therefore more participative, who supported one of the Nupes’ candidates (41%). However, as mentioned, the presidential election mobilises more voters, among young age groups and even among young people from the working classes. In the first round of the presidential election, 16% of 18–24-year-olds voted for Marine Le Pen.

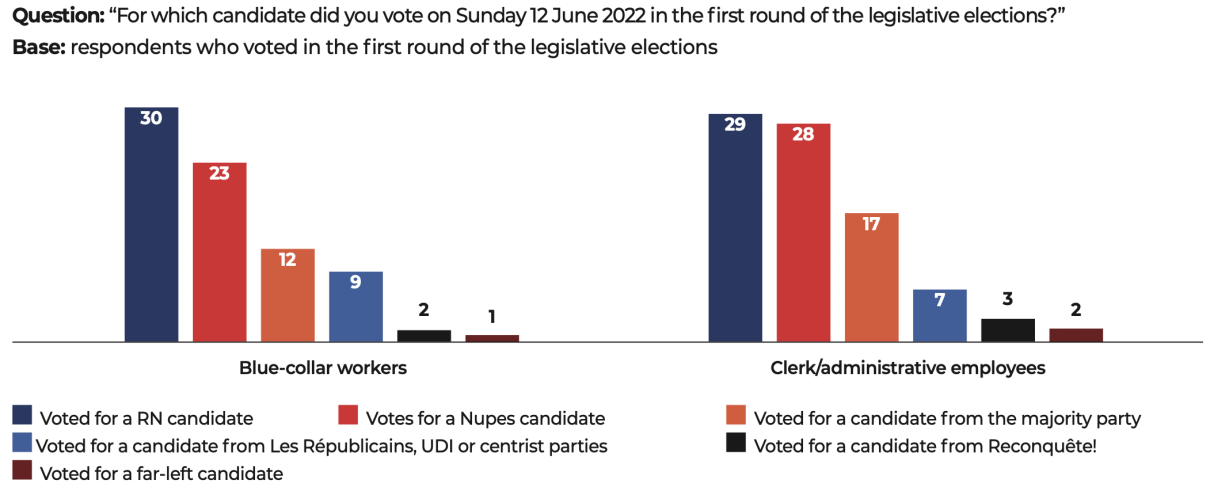

The RN, the leading party among workers and employees

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

The profile of RN voters in the first round of the legislative elections

Question: “For which candidate did you vote on Sunday 12 June 2022 in the first round of the legislative elections?”

Response: “a candidate from the Rassemblement national”

Base: all respondents who voted in the first round of the legislative elections

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

See Games Changers-Ipsos-Sopra Steria “1er tour des élections législatives. Sociologie des électorats et profil des abstentionnistes”, ipsos. com, June 2017.

Ibid., p. 21.

The difficulties of the RN are largely offset by the fact that it is making significant progress in the upper social categories. In the first round of the 2017 legislative elections, 11.5% of managers and 11% of those with intermediate professions voted for the Front National; in 2022, in the first round of the legislative elections, the RN vote has gathered 13% and 16% respectively. The consequence is significant, even crucial. Indeed, the 2022 electoral cycle showed that it is by becoming more socially diverse and the ability to appeal to a wider range of classes that the RN is capable of better results, first and foremost in terms of voter turnout. In 2017, 57% of Marine Le Pen’s voters in the first round of the presidential election did not take part in the first round of the legislative elections in 2022 – this figure dropped to 45%.

By going from 8 MPs in 2017 to 89 MPs in 2022, the RN has enjoyed a historic political victory, far ahead of the 35 MPs elected under the proportional system in 1986, the best result for the FN/RN up to that point. The strong electoral progression of the RN allows for it to be emancipated from the proportional system. For Marine Le Pen’s party, the constitution of the first opposition parliamentary group opens the pathway to new perspectives, offering it unprecedented means, notably in terms of human resources and financial resources, and the possibility of playing an important role within the National Assembly, which has suddenly become one of the most important places in political life.

Abstention from voting disguises a larger share of the vote for the Rassemblement national

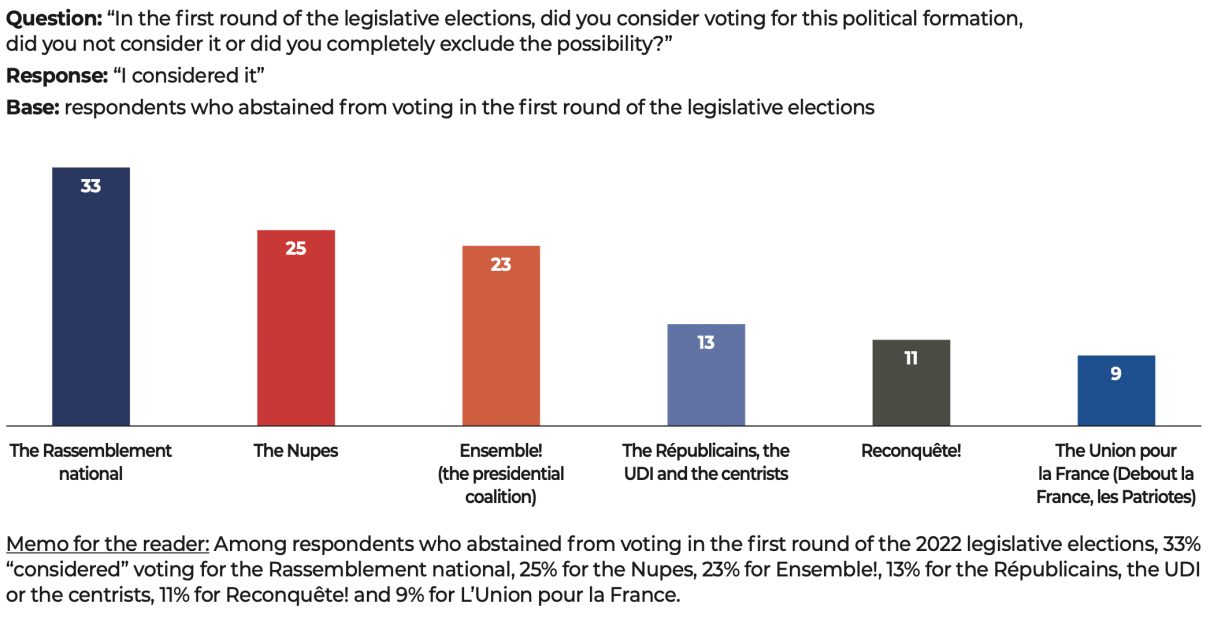

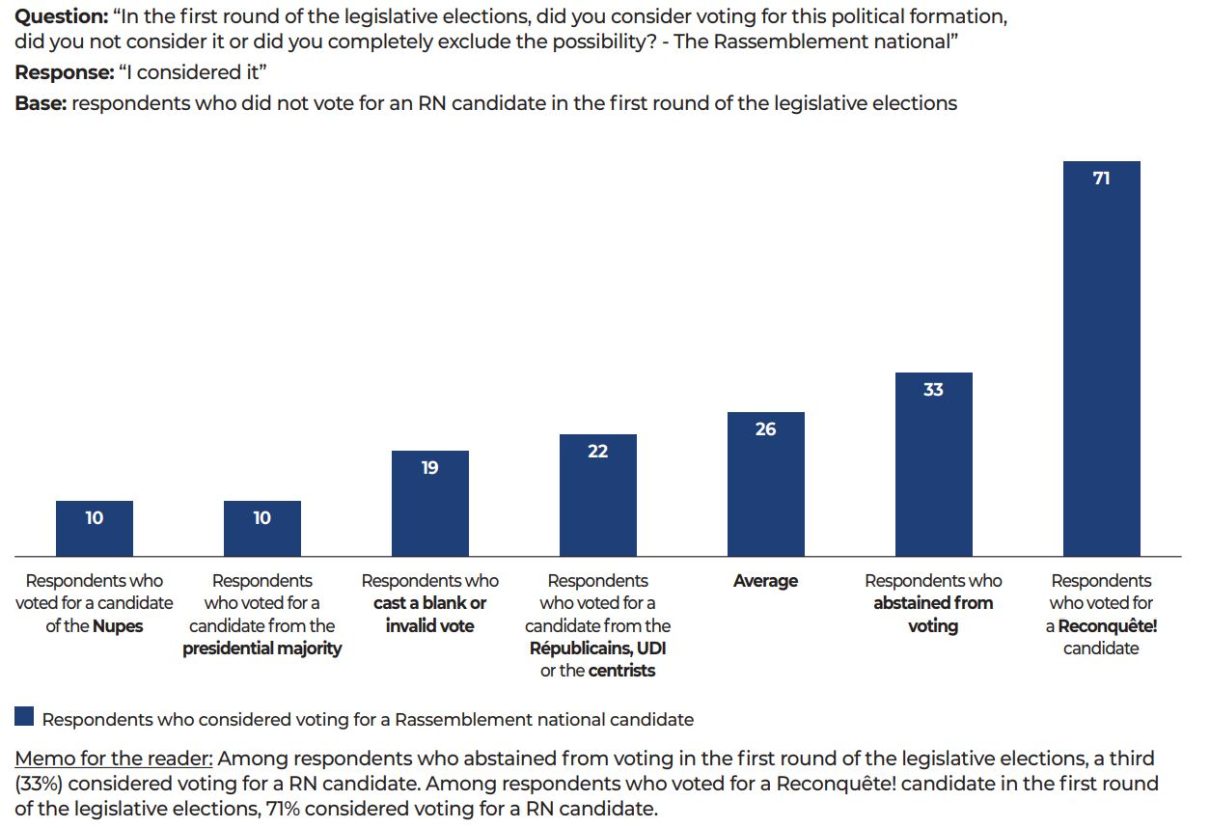

We have seen that while the RN has become the first opposition group in the National Assembly, only 55% of Marine Le Pen’s voters in the first round of the presidential election voted in the first round of the legislative elections. It appears that a third of those who abstained from voting (33%) in the first round of the legislative elections considered voting for an RN candidate, 25% for a Nupes candidate and 23% for the presidential majority. Because of its protest dimension, abstention from voting is therefore a real source of potential future votes for the RN.

58% of voters close to the RN justify their abstention from voting by a form of protest

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Memo for the reader: Among respondents close to the RN, 20% abstained from voting because it is their “way of protesting against the current political system”.

Abstention from voting as a form of protest and political affiliation

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Voters who feel close to the RN, Reconquête! or EELV mostly abstained from voting in the legislative elections

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Those who abstained from voting offer more electoral reserves to the RN than to the Nupes

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Memo for the reader: Among respondents who abstained from voting in the first round of the 2022 legislative elections, 33% “considered” voting for the Rassemblement national, 25% for the Nupes, 23% for Ensemble!, 13% for the Républicains, the UDI or the centrists, 11% for Reconquête! and 9% for L’Union pour la France.

The uncertain survival of mainstream political parties

See Dominique Reynié, “L’élection se mue en instrument de protestation contre le pouvoir plus que de délégation du pouvoir”, remarks collected by Benoît Floc’h, Le Monde, 19 April 2022

It was in the first round of the presidential election of 21 April 2002 that the total number of “mainstream candidates” in the first round of a presidential election became a minority for the first time, i.e. 38%, by adding the scores of Jacques Chirac (13.7% of those registered), Lionel Jospin (11.2% of those registered), François Bayrou (4.7% of those registered), Jean-Pierre Chevènement (3.7% of those registered) and Alain Madelin (2.7% of those registered). A maximum of 44.1% of registered voters can be obtained by adding Noël Mamère (3.6% of registered voters), Corinne Lepage (1.3% of registered voters), Robert Hue (2.3% of registered voters) and Christine Boutin (0.8% of registered voters).

In a genuine democratic regime, there is an incompressible level of abstention from voting, blank votes and protest votes, making up what we call here electoral protest. Such protest does not interfere with the proper functioning of the political and governmental system as long as it remains marginal, i.e. as long as the political system is able to control its causes. This is no longer the case today. If we consider the first round of the presidential election, on 10 April 2022, the combined total of abstentions from voting, blank votes and protest votes represented 68% of registered voters13 so in terms of votes cast, the protest vote accounts for the majority (55.6%) for the first time. In 2017, this total stood at 48.4% and at 29.6% on 21 April 2002. In twenty years, the total protest vote has thus increased by 26 points. Having become the majority, the protest vote remains dispersed among several candidates, even if two of them concentrate the largest share: on 10 April 2022, 45% of the votes cast were gathered around the candidacies of Marine Le Pen (23.1%) and Jean-Luc Mélenchon (21.9%) alone.

For more than twenty years, the observation of the total scores of mainstream political parties and candidates, both on the left and on the right, has revealed a collapse of their electoral base. In 2022, Emmanuel Macron, Valérie Pécresse and Anne Hidalgo together do not reach a quarter of the registered voters (24.8%). To allow for minor conjectures, let us specify that, even if we include Yannick Jadot (3.3% of registered voters) and Éric Zemmour (5.1% of registered voters) in the list of mainstream candidates, the total of all government candidates, right-wing, left-wing and Macron candidates combined, would only ever represent 33.1% of registered voters. In 2017, during the first round of the presidential election, this total represented 38.2% of registered voters (Emmanuel Macron, François Fillon and Benoît Hamon), 50.6% in 2012 (François Hollande, Nicolas Sarkozy and François Bayrou) or, in the latter case, almost 65% of the votes cast14.

The ballot box and public opinion: the dual victory of the Rassemblement national

While protest votes on the right and the left have increased significantly in the 2022 election cycle, the success of Marine Le Pen and the RN has been more noticeable. This success is evident in the ballot box, as shown by the results of the presidential and legislative elections, but also in public opinion: there is a greater acceptance of the RN’s ideas.

The growing acceptance of the Rassemblement national by the French public

See Victor Delage, The conversion of Europeans to right-wing values. France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, Fondation pour

l’innovation politique, May 2021, 40 p.

Since it is now the primary opposition group in parliament, it is important to know whether the RN is still considered a protest party. The efforts to moderate the party’s image since 2017, when it was still the FN, have been the subject of abundant commentary which is already the mark of a certain success in the strategy of mainstreaming the party, or the so-called “de-demonization” of the FN. The move to the RN implies a break with the genealogy of the FN and of the father Le Pen. The mothballing of a programme historically hostile to Europe and the euro accompanied this change. Yet the election of 89 MPs is not only the result of these efforts of moderation. It is also the product of a general scepticism towards political forces and government institutions. The evolution of the RN in public opinion is also the result of society’s shift to the right, particularly because of the importance of concerns such as safety, the difficulties associated with the integration of immigrants, and Islamism, fuelling a negative relationship with globalisation, which is perceived by the majority as a threat rather than an opportunity15, and leading to a demand for the assertion of public power in these areas, and subsequently to frustration and exasperation on the part of many voters not being heard on this crucial point.

The historical conditions in which our national debate and, more broadly, our public space have been formed mean that these issues, considered illegitimate for sometimes confusing reasons, have been left in the hands of the right and even more so of the populist right. These concerns are deemed to be intrinsically right-wing rather than left-wing. The mainstream left has therefore not considered them, de facto leaving aside the defence of the working classes and immigrant suburbs, secularism, public services, safety, the most fundamental of all public services, or equality, a value that is supposed to be unanimous, and the object of insatiable demands, except in these areas. The neglect of these issues by the left and also by the classic right has given the FN and then the RN a de facto programmatic monopoly, like a distinctive sign, initially sulphurous, but gradually beneficial, as these concerns have gained in importance. These issues now raise concerns that go well beyond the working classes. So, when asked: “In the June 2022 legislative elections, 89 RN MPs were elected, forming the largest opposition group in the National Assembly. Do you think this is…?”, almost half of the respondents (47%) answered “a good thing”. A third (33%) thought it was a bad thing and 19% answered “neither good nor bad”. Of course, almost all respondents (95%) who voted for a RN candidate in the first round of the legislative elections consider it a “good thing”, but 34% of those who voted for a Nupes candidate and 22% of those who voted for a presidential majority candidate consider the election of 89 RN MPs as a good thing.

Half of the respondents (47%) think that the election of 89 RN MPs is “a good thing”

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

This view is shared by voters living in rural areas (50%) and in towns with between 2,000 and 19,999 inhabitants (52%), but also in urban areas (48%) outside the Paris region. Despite this, 41% of people living in the Paris region share this positive view of the results of the RN in the 2022 legislative elections. This assessment is found in roughly the same proportions among the lower socio-professional categories (50%) and the upper socio-professional categories (47%). Major differences remain. For example, the “degree effect” has not entirely disappeared. The arrival of the new RN MPs is more appreciated among the least qualified (56%) than among respondents with a bachelor’s degree (46%) or a degree higher than bachelor’s (39%). However, it should be noted that the level of favourable opinion of the RN is now high in all social categories and no longer only among the working classes.

A third of voters close to left-wing parties find the arrival of 89 RN deputies

in the National Assembly “a good thing”

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

The success of the RN in the legislative elections opens up the possibility of the institutionalization of Marine Le Pen’s party. All the more so as, at the same time, the growing acceptance of the RN’s ideas testifies to its growing acceptance in public opinion. The two parties with which voters feel most in agreement are EELV and the RN. In both cases, 39% of respondents either “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” with the ideas defended by the party. However, although EELV and the RN are winning this battle, of all the political parties, only the RN attracts such a high proportion of voters who “strongly agree” with its ideas (17%).

Support for the RN’s ideas in public opinion

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

In the first round of the 2022 legislative elections, the RN’s ideas appealed to 91% of Reconquête! voters. This is also the case for a significant proportion of LR voters. Thus, 37% of LR-UDI voters and various centrist candidates say they agree with the ideas of Marine Le Pen’s party. It should be noted that the age criterion has little effect on support for the RN’s ideas: 36% of 18–24-year-olds say they “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” with these ideas, as do 37% of 25–34-year-olds and 40% of 35–49-year-olds, 42% of those aged 50-64 and 35% of those aged 65 and over.

The RN is one of the political parties with the most positive image

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Acceptance of the RN by age group

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Embodied by the LFI, left-wing populism does not attract the same level of support. With 28% of voters who say they “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” with LFI’s ideas, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s party is clearly outpaced on this level by the RN (39%). However, with 48% of voters who “strongly disagree” with his ideas, LFI becomes, after Reconquête! (54%) and DLF (49%), one of the three political formations whose ideas are the most rejected.

Less than half (47%) of right-wing voters see the RN as a danger to democracy

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

The right is growing closer to the RN: right-wing voters identify more with the ideas of the RN than with those of the LR

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

This data was taken from the second wave of our survey, administered in the days following the second round of the presidential election, between 28 April and 2 May 2022, among a sample of 3,052 people.

Finally, in the context of a political upheaval on the right, it is important to note that, among voters who position themselves on the right, less than half (47%) consider the RN to be dangerous for democracy16. An even smaller proportion consider it to be ‘’xenophobic’’ (44%). Conversely, the majority of right-wing voters consider the RN to be capable of governing (59%), believing that it advocates for a society in which they would like to live (57%).

More than two thirds (71%) of those close to the RN do not consider Marine Le Pen to be a far-right candidate

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

For the radical Left and the protest Right, Marine Le Pen is not far right

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

As we will see below, a fraction of Jean-Luc Mélenchon and LFI supporters will not hesitate to vote for Marine Le Pen or RN to try to defeat Emmanuel Macron in the presidential election or one of his candidates in the legislative elections. The same is true, symmetrically, for a fraction of Marine Le Pen and RN voters. To illustrate this, we should note that in the legislativeelections, in the case of constituencies where, in the second round, the RN was opposed to Ensemble!, nearly a third (30%) of Nupes voters in the first round answered that their second round choice had been primarily motivated by their desire to “strengthen the opposition to Emmanuel Macron”.

It is obvious that the electoral development of one party, whether old or new, necessarily comes at the expense of others and, potentially, at the expense of abstention from voting. It is these electoral transfers – the shift from abstention to participation and the transition from one party to another – that produce electoral movements, whether temporary or long-lasting. In the case of the FN, during its electoral take-off in the 1980s, new voters came from the left as well as the right of the political spectrum. In 2022, the RN benefited from new transfers from the mainstream right. Thus, 11% of François Fillon’s voters in 2017 voted Marine Le Pen in the first round in 2022, while 18% preferred Éric Zemmour. Similarly, 8% of Fillon voters in 2017 voted for a RN candidate in the first round of the legislative elections, and 9% for a Reconquête! candidate. Zemmour’s entry onto the political scene seems to have drawn an additional fraction of the LR electorate into an airlock leading them eventually to vote for Le Pen, which they may not have done initially. At first, the leader of Reconquête! was able to hold the attention of a fraction of the mainstream right, which then shifted to Marine Le Pen and the RN, particularly in the second rounds of the 2022 presidential and legislative elections. This quantitative contribution could also account for the sociological evolution of the Le Pen/RN 2022 vote, where there is a greater proportion of voters from the middle and wealthy class. However, as we have already indicated, the excellent results of Marine Le Pen’s party in the legislative elections are also due to the mobilisation of voters from the protest left in her favour18: 24% of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters in the first round of the presidential election voted Marine Le Pen in the second round, as did, although the proportions relate to marginalised electorates, a fraction of the voters of Fabien Roussel (26%), Anne Hidalgo (15%), and Yannick Jadot (6%).

The RN achieved its best score in the June 2022 legislative elections, but it still has stockpiles of votes: on average, 26% of voters who did not vote for the RN considered doing so, compared to the 21% of voters who did not vote for the Nupes after considering it and the 20% of those who did not vote for Ensemble! but considered doing so.

Of the three main presidential candidates, Emmanuel Macron, Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the RN candidate relatively has the lowest level of rejection (53%) and the highest level of support (36%). Given the role played by a public figure in a political competition, particularly in a system structured around a presidential election, a role that is further enhanced by the new public media space and social networks, the image of a political party tends to merge with the face of its leader. The “normalisation” of the FN/RN owes much to the change of leader, in the transition from Jean-Marie Le Pen to Marine Le Pen. The shrinking, or even disappearance, of the mainstream political parties, the PS and LR, both of which still lack an authoritative leadership, contributes to placing the populists of the right and the left at the centre of the political arena. Electoral judgment is a relative judgment. The absence of credible competitors representing moderate parties, or their insufficient influence, mechanically favours the visibility and acceptance of less conventional candidates.

The RN has electoral potential on the right and among those who abstained from voting

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Marine Le Pen is no longer particularly rejected by the public

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

An incomplete normalisation. Marine Le Pen attracts more support than the Rassemblement national

Respondents were given a choice between the following three propositions: “his/her personality”; “his/her programme”; “his/her ideas”.

In the second wave of this survey, conducted after the second round of the presidential election, we asked voters who did not vote for Emmanuel Macron – either those who voted for Marine Le Pen, who cast a blank vote or who abstained from voting – to name the main reasons behind their decision, among a series of propositions19. Among the reasons for not voting for Emmanuel Macron, “his personality” weighed as heavily (34%) as “his political ideas” (33%) and “his programme” (32%).

Conversely, among voters who did not vote for Marine Le Pen – i.e. who either voted for Emmanuel Macron, voted blank or abstained from voting – 11% gave “his personality” as the main reason, 21% “his programme”. However, there are still 67% of respondents who mention “his political ideas”.

Opinion of Marine Le Pen by political affiliation

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

Following the second round of the presidential election, a significant proportion (42%) of voters believe that the RN candidate has the stature of a president, consider her to have “a good plan for the future of France” (44%) and believe that she “tells the truth” (44%).

Finally, it should be noted that Marine Le Pen is not considered to be worrisome by a third of respondents close to LO or the NPA (35%), and the same is true of those close to the PC-LFI (34%).

The convergence of these theoretically opposed universes occurs at least on the radical and authoritarian approach to political action. A significant proportion of LO-NPA supporters (59%) said they agreed with the idea that Marine Le Pen “has a good plan for the country”. This opinion is also shared by 35% of those close to the PC-LFI, i.e. mainly LFI, given the respective electoral weight of the PCF and LFI.

In June 2022, the French expect Édouard Philippe and Marine Le Pen for the presidential election of 2027. To be continued…

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

See the numerous data available on the “France politique” website of journalist Laurent de Boissieu.

It should be noted that a portion of the population resists this fear, particularly on the left. Thus, when asked about the risk of an “attack on fundamental freedoms”, 39% of those close to the PCF-LFI believe that this risk does not apply to Marine Le Pen, as do 31% of those close to LO-NPA.

Marine Le Pen was Emmanuel Macron’s main competitor for access to his first five-year term in 2017, and in 2022 she remained his main opponent. Remarkably, despite her three successive defeats, her role does not seem to be taken away from her for the upcoming presidential election in 2027. Voters who want Marine Le Pen to run for a fourth time are found both among those close to the RN (96%), those close to Reconquête! (81%), but also among a significant proportion of those close to LR (46%) and those who are not close to any political party (34%).

In a more troubled France, the RN causes less concern. The year 2022 seems to be the year of its institutionalisation. This is apparently the logical consequence of its successful results. This so-called “far right” party is now capable of occupying first place in the electoral competition. This is not a new development, as this was already the case in 2014, during the European elections (24.9%); in 2015, during the regional elections (27.7%), and in 2019, during the European elections (23.3%)20.

However, the hypothesis of the institutionalisation of the RN does not account for the its new position in the political landscape. Indeed, its electoral results cannot be explained if we do not take into account the protest element, which is contradictory to the notion of its institutionalisation. The FN, since its creation on 5 October 1972, and the RN, from 2018 onwards, have never ceased to claim the status of a political party “unlike the others”, “the political party that says out loud what the French are thinking”, waving the promise of a break with the past. In addition to systematically taking on popular concerns side-lined by both the government parties and the media, it is the use of an “anti-system” rhetoric and posture that has allowed the FN/RN to aggregate over time a large number of voters disappointed with the right and the governing left, and even those disappointed with electoral participation, and ultimately to capture the main share of this varied accumulated anger.

One wonders how the RN could survive its institutionalisation, i.e. the erasure of the radical promise on which it has thrived for half a century, the weakening of its populist discourse, which denounces false democracy, corrupt elites, a stateless Europe, finance and globalisation, etc. Between 1972 and 2017, it is to this more or less explicitly radical programme that the FN/RN owes a large part of its media visibility and its electoral momentum; this is how it managed to capture the attention and then the support of an increasingly large number of diverse voters, and in the end, voters of all

political persuasions.

However, the institutionalisation of the RN and the greater acceptance of Marine Le Pen in public opinion are not yet enough to ensure her presidential stature. The scepticism and concern that she ignites are still based on the risks that she would pose to freedom. Indeed, the RN candidate is still considered to be “worrisome” by a preponderant share of respondents (55%), while a majority (54%) consider that she would infringe on fundamental freedoms21.

Nonetheless, public scepticism is also, and probably more so, related to the risks that the election of Marine Le Pen would pose to the euro. The broad and constant support of public opinion for the European Union, and even more so for the euro, limits the process of institutionalisation of the RN, which is a prerequisite for the further electoral progress of the party and for the fulfilment of Marine Le Pen’s presidency.

Voters are largely in favour of the European Union and the euro

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – September 2022

See Dominique Reynié (ed.), What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2017, 320 p.; Democracies Under Pressure, volume I, “The themes”, 156 p. ; volume II, “The countries”, 120 p., Fondation pour l’innovation politique (survey carried out in partnership with the International Republican Institute), May 2019; Dominique Reynié (ed.), 2022, the Populist Risk in France, op. cit.

Dominique Reynié, Anti-Semitic Attitudes in France: New Insights, Fondation pour l’innovation politique-AJC Paris, March 2015, 48 p.

On the subject, see François Legrand, Dominique Reynié, Anne-Sophie Sebban-Bécache and Simone Rodan-Benzaquen, An analysis of antisemitism in France – 2022 Edition, Fondation pour l’innovation politique-AJC Paris, March 2022, 48 p., see also Dominique Reynié and Simone Rodan-Benzaquen, Analysis of anti-Semitism in France – 2019 Edition, Fondation pour l’innovation politique-AJC, January 2020, 30 p.

In its work on the subject, the Fondation pour l’innovation politique has identified three main sources of antisemitism: the extreme left, the extreme right and people of the Muslim faith. The statement that “Jews have too much power in the field of economy and finance” is shared by 51% of respondents of Muslim faith according to both the 2019 and 2022 editions of our An analysis of antisemitism in France, op. cit.

Dominique Reynié, Anti-Semitic Attitudes in France…, op. cit., p. 28.

It should be noted, once again22, that even among those close to the RN, the wish to remain in the European Union (62%) and to keep the euro (70%) is still the majority opinion. However, only a third (33%) of voters consider that, as president, Marine Le Pen would have been able to protect the euro. By comparison, 60% of voters credit Emmanuel Macron with this ability. Voters’ attachment to the European Union, and in particular to the euro, is blocking the progression of some of the ideas that have historically made the FN/RN so strong. For the time being, the French do not want a return to political and monetary sovereignty. It is obvious that the RN and Marine Le Pen have scaled down their ostentatious and vehement hostility to Europe. The comparison between the two debates between the two rounds, in 2017 and 2022, bears witness to this. A shift may be underway, but it is not clear what would happen to a populist party that becomes pro-Europe and pro-euro. The Europeanisation of populists is also a modality of their integration into the conventional political system. Institutionalisation has a price.

Finally, we should note that the ideological origins of the FN have left their mark. There are few more powerful indicators of a movement’s incompatibility with the idea of democracy and the republican ideal than antisemitism. The RN is the heir of an extreme right-wing party, the FN, whose history intertwines with that of French antisemitism. As the work we are developing on this subject in partnership with AJC Paris demonstrates, anti-Semitism in France has changed since the turning point of the 1990s. Alongside extreme right-wing antisemitism, there has been a revival of extreme left-wing antisemitism, particularly in relation to the rise of French Muslim antisemitism23. These three segments of the population are a minority, but a highly active one24. Antisemitism is particularly widespread among French people close to the RN and LFI; it is also widespread among respondents of Muslim faith or culture. For example, the statement that “Jews have too much power in the sectors of economics and finance” is shared by 39% of the electorate of Marine Le Pen and 33% of those close to the RN, 33% of the respondents within the electorate of Jean-Luc Mélenchon and 34% of those close to LFI, compared to 26% in the general population (and 51% of the respondents of the Muslim faith)25. However, it should be noted that between 2014 and 2021, support for the idea that “Jews have too much power in the sectors of economics and finance” remained at the same level for those close to FdG/LFI (34% and 33% respectively), while the proportion of those close to FN/RN who share this idea is in sharp decline, down from 50% in 2014 to 33% in 202126.

In right-wing France, the dilemma of Les Républicains: Joining forces with Ensemble! or with the Rassemblement national?

While the political re-composition of France is still difficult to decipher, the reshaping of the political right is already underway. The most recent elections bear witness to this. The scores of the mainstream right are historically low, but the electoral performance of Marine Le Pen in the presidential election, followed by the arrival of 89 MPs in the National Assembly, has placed the RN at the heart of the political game, and all the more so as the absence of an absolute majority puts the National Assembly at the centre of the emerging geography of political power.

In 2022, two thirds of Emmanuel Macron’s voters can be classified as right-wing

These data come from a question asking respondents to position themselves on a left-right scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is the most left-wing position and 10 the most right-wing position: those from 0 to 4 are considered left-wing, 5 in the centre, and 6 to 10 right-wing. Respondents also have the option of choosing not to position themselves on this scale.

For these questions, the items that we considered markers of a rather left-wing value system were the following: “Students with educational difficulties should not be in the same classes as those without educational difficulties”; “People who work should pay to finance the retirement of those who are retired”; “We should make an effort to increase taxes for everyone, even if I don’t pay any today, so that we can pay off the debt for it to be less of a burden on future generations”; “Most immigrants share our country’s values and this represents cultural enrichment”; “We need more control from the State and less freedom for companies”; “Even for the unemployed who really want to, it is difficult to find work”; and, lastly, “To protect the population, the police can already use their firearms in a satisfactory manner”.

At the same time, Emmanuel Macron and his party have managed to bring together a significant proportion of voters from the mainstream right. More than five years after the creation of his party, which was intended to be “neither left-wing nor right-wing”, the Macron electorate is nevertheless largely right-wing: half (47%) of Emmanuel Macron’s voters in the first round of the presidential election positioned themselves on the right of the political spectrum, 19% in the centre, 20% on the left while only 12% did not position themselves. However, it appears that Macron’s voters who position themselves in the centre or who do not position themselves on the left-right axis are often closer to the ideas of the right than to the left, according to the results of our survey.

In order to calculate the real weight of the right, it is therefore necessary to take into account a proportion of Emmanuel Macron’s voters27. We added to the weight of the scores achieved by the right-wing candidates, excluding Emmanuel Macron, the weight of the voters who voted for him in the first round of the presidential election and who are positioned themselves on the right of the political spectrum, i.e. 47% of all his voters. On the other hand, we have of course excluded Emmanuel Macron’s voters who positioned themselves on the left.

Secondly, based on the responses to a series of items, we were able to determine whether the respondents who voted for Emmanuel Macron in the first round of the presidential election and who position themselves in the “centre”, or who “do not position themselves” at all on the left-right scale, are right-wing or left-wing voters. Among the seven pairs of items tested as revealing a left-right divide, in our opinion, therefore leading to the expression of a right-wing or left-wing preference, we isolated the responses that could be considered markers of a right-wing value system, namely the following responses:

Item 1: “People who work should be able to put money aside as they see fit to finance their own retirement” (the other answer, revealing a rather left-wing value system, is specified in footnote28).

Item 2: “Efforts should be made to reduce public spending, including the ones I benefit from today, so

that we can pay off the debt and lessen the burden of it for future generations”.

Item 3: “Most immigrants do not share our country’s values and this creates problems of cohabitation”.

Item 4: “We need more freedom for companies and less control from the State”.

Item 5: “The unemployed could find work if they really wanted to”.

Item 6: “To better protect the population, the police should be able to use their firearms more easily”.

Item 7: “Students with educational difficulties should not be in the same classes as those without educational difficulties”.

For Emmanuel Macron’s voters in the first round of the presidential election who position themselves “in the centre” or who “do not position themselves” on the left-right scale, we measured an average level of support for the seven items that mark a right-wing value system. For example, among Emmanuel Macron’s centrist voters (i.e. those who position themselves in the centre), we took into account the 17% who think that “people who work should be able to put money aside as they see fit to finance their own retirement”, the 50% who think that “most immigrants do not share our country’s values and this causes problems of coexistence”, the 66% who think that “the unemployed could find work if they really wanted to”, etc. The sum of the responses to these seven items provides a score of support for right-wing issues (here, in this case for Emmanuel Macron’s centrist supporters, it is 342 points, which is the total of the percentage points found from the responses of Emmanuel Macron’s supporters). Divided by the number of items, i.e. by seven, this allows us to determine an average level of support for these right-wing values, i.e. 48.9% in the case of Emmanuel Macron’s centrist voters. Thus, among these Emmanuel Macron voters, the share of voters who share a right-wing value system is estimated at 48.9%. We therefore add to the total weight of the right-wing electorate 48.9% of the 19% of Emmanuel Macron’s centrist electorate, i.e. 9.4% of the total number of Emmanuel Macron’s voters in the first round of the 2022 presidential election.

We proceeded in the same way for voters who cast their ballot for Emmanuel Macron in the first round of the presidential election but who “do not position themselves” on the left-right scale. The level of support for the seven right-wing items is 371 points, which, divided by seven, gives us an average level of support of 53%. We therefore included in the weight of the right-wing electorate 53% of the 12% of Emmanuel Macron voters who do not position themselves on the left-right scale, which represents 6.5% of the total number of Emmanuel Macron voters.