2024-2029: The populist upsurge in Europe, electoral reality and institutional limitations

Arnaud Danjean | 10 avril 2024

Arnaud Danjean is a Member of the European Parliament and a member of the EPP. He did not wish to stand as a candidate in the 2024 European elections.

If we are to believe the commentators, an inevitable surge of right-wing « populist » parties (sovereigntists/radical right) is set to sweep the continent in the European elections next June. According to the more pessimistic forecasters, this electoral success will lead to a total reshaping of the European institutions, and could even hinder their functioning. While predicting an electoral rise of radical right-wing parties entails little uncertainty, suggesting a potential paralysis or complete upheaval of the system appears more speculative.

I. A VARIETY OF POPULIST RIGHT-WING FORCES, NOT ONE SINGLE POPULIST RIGHT

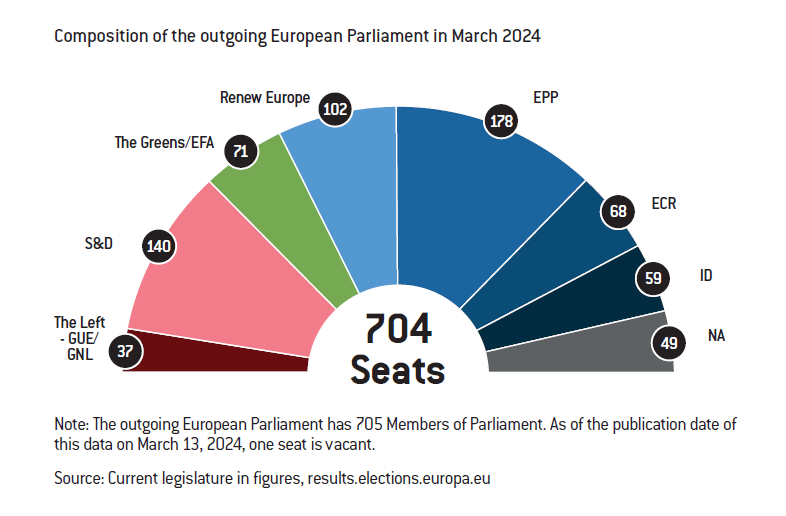

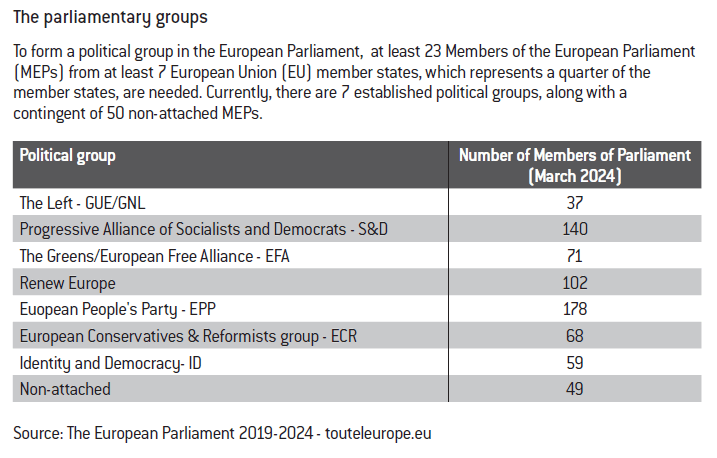

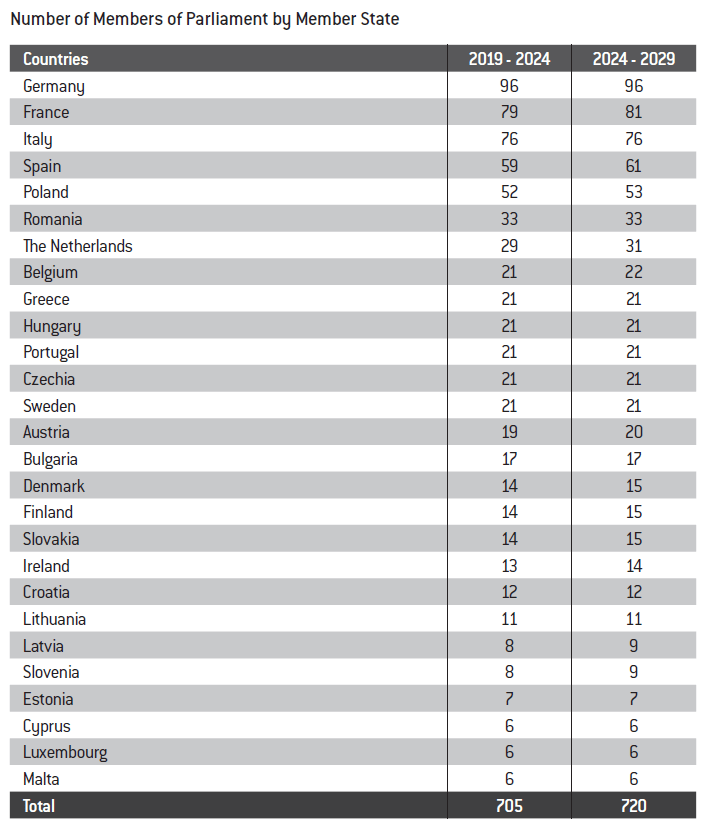

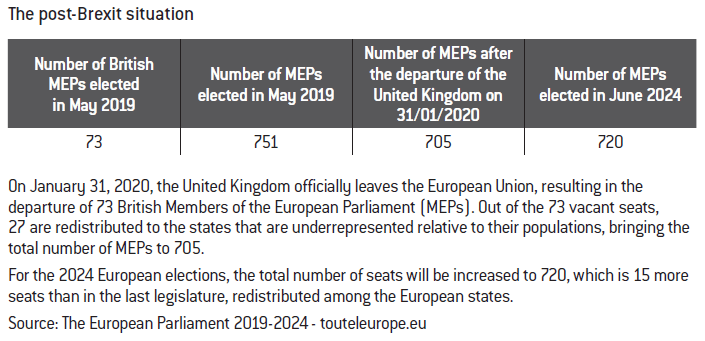

Before looking ahead to the possible results on June 9, we need to consider the current state of EU parliamentary forces: the so-called « populist » right comprises around 140 MEPs (out of 705, i.e. less than a quarter of the European Parliament) and is divided into 3 distinct parliamentary groups.

These divisions owe nothing to chance or to bureaucratic arguments in Strasbourg, but reflect very significant ideological, historical and tactical cleavages, many of which will persist in the months and years to come.

• The main « populist » group, ECR (The European Conservatives and Reformists), has 68 elected members, mainly from the Polish PiS (Law and Justice Party) and Fratelli d’Italia (Giorgia Meloni’s party).

• The second, more radical group is ID (Identity and Democracy), whose mainstays are the Lega, RN (Rassemblement National) and AFD (Alternative for Germany). It has approximately sixty elected members.

• The non-attached group includes a sizeable contingent of Hungarian Fidesz MEPs (12 members), whom none of the other groups were willing to accept after they left the EPP in 2020.

These movements have never managed to join forces within the same group, due to divergences linked to their own national trajectories, but above all to their different approaches to major issues.

• The war in Ukraine has made it clear that there are stark differences in positions. On one side, there’s strong support for Ukraine and transatlantic cooperation, particularly from the ECR group. On the other, there are ambiguities or even support for Moscow’s stance, especially from the ID group. Given the strategic importance of this issue, the key players (NATO, USA, Russia) are unlikely to budge, preventing further rapprochement.

• Global positioning vis-à-vis the EU is also a contentious issue. Beyond the shared criticism of technocratic excesses and a resistance to move towards more integration/federalism, there is a clear difference in approach between the conservative parties currently or formerly in power (in Italy, but also in Poland and even in Hungary) and their radical counterparts who remain in opposition. We are thus witnessing a form of pragmatic shift on the part of the populists in power, who – while retaining a highly virulent anti-Brussels rhetoric for internal use – are starting to engage with European mechanisms, particularly in financial terms. The evolution of Giorgia Meloni is obviously

the most blatant illustration of this, but even the Polish and Hungarian cases have shown that the most incisive leaders against Brussels have never crossed a certain line. This sets them apart from groups like the ID, where the desire to leave the EU is always present, as seen in recent campaigns by parties like the AFD explicitly advocating for an EU exit.

• Even on seemingly consensual issues for all radical right-wing forces, deep divisions persist. Immigration, for example, is the glue that binds all these sovereigntist parties together. However, after closer examination, we see that policies differ from country to country beyond the common anti-immigration stance. National interests often outweigh ideological similarities. For example, the radical right in a country like Italy, which serves as a first entry point for migrants, may advocate for European solidarity and the relocation of migrants.

On the other hand, right-wing groups in Central Europe or those not in government in Western countries staunchly oppose these ideas and may even consider them as grounds for conflict.

The division within the right-wing is based on differences that go beyond surface-level disagreements, they touch upon fundamental beliefs as well as tactical considerations. They won’t simply vanish after June 2024.

Questions of leadership will be amplified by changes in the balance of power within each of the populist groups:

• Within ECR, Giorgia Meloni’s Italians will supplant the Polish PiS, shifting the group’s center of gravity to the center-right.

• Within ID, the Lega will lose its pre-eminence to the RN, but also to the AfD, whose radicalism is frightening, even to its own allies.

• The acceptance of Fidesz within these right-wing groups still raises questions. Its radicalism aligns it more with the ID, but its status as a governing party leans it towards seeking an alliance with the ECR. However, within the latter, it might end up being seen as a lesser partner compared to strong leaders such as Giorgia Meloni.

The undeniable quantitative surge of the radical right will therefore optically conceal a qualitative fragmentation.

II. A EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT WITHOUT A MAJORITY? NEITHER NEW NOR DANGEROUS!

In the French public perception, the European Parliament has been run or decades by a « coalition » made up of 4 major « pro-European » forces: EPP (center-right), Renew Europe (center), S&D (social-democrats) and The Greens. These 4 groups account for just over half of all elected MEPs (382 out of 705).

But nothing could be further from the truth, particularly in light of the last mandate.

• There has never been a formal coalition agreement among these groups. While they share a basic commitment to the European project, they are also quite diverse. There’s never been a preset agreement; at most, they’ve had some common ground and consulted each other on parliamentary matters and appointments. However, when it comes to final votes, they decide independently on a case-by-case basis.

• In the past five years, the volatility of majorities has reached unprecedented levels. Issues like the Green Deal, industry, energy, immigration, and budget have deeply divided these political groups, both among themselves and internally. National interests have played a significant role, affecting all European political groupings. Various combinations of alliances have emerged on each of these major issues, highlighting the complexity of the political landscape within the European Parliament.

The extreme volatility of political alliances was vividly demonstrated by the pivotal vote in July 2019 to confirm Ms. Von der Leyen as President of the European Commission. Had the logic of the pro-European majority bloc prevailed, the investiture should have been a formality, with over 400 votes in her favor. However, she barely mustered more than 350, exposing defections within each group and making it impossible to interpret the balance of power solely in terms of pro- or anti-European sentiments.

The fundamental truth of the European Parliament is that each vote forms its own majority, and this dynamic is unlikely to be fundamentally challenged by the populist upsurge:

• Two major groups (EPP and S&D) are expected to maintain strong positions (Renew and the Greens are projected to experience significant losses according to current projections).

• There is no scenario where right-wing sovereigntist forces can independently form an alternative majority.

• The threat of blocking Parliament exists mainly in the rhetoric of struggling political forces. While « right-wing » majorities are more probable than « centre-right » majorities, it’s important to note that being « right-wing » doesn’t necessarily equate to blocking, as some right-wing parties are willing to support European legislation, as the Italians have done – even the Lega, which is less radical than Salvini himself, has participated constructively in the adoption of certain texts.

Parliamentary deadlock is rare, but can occur when the slightest compromise becomes impossible.

However, this lack of a negotiated solution can be triggered by radicalism and maximalism, which aren’t exclusive to populist opposition.

In the 2019-2024 term, this situation arose on an environmental text when it was the pro-European forces (Greens and Renew) who refused to make any concessions on ambitions deemed unrealistic and unworkable by a majority of the Parliament. Consequently, the text was rejected without the possibility of presenting a more pragmatic alternative.

The cause of such deadlock cannot be solely attributed to right-wing populism; the intransigence of « pro-European » groups also plays a significant role. While scenarios like this may become more common, they are democratically surmountable if the pursuit of compromise genuinely motivates « core » political forces, which would still constitute a potential majority, even with the inclusion of « responsible » populists.

A case-by-case approach will remain the rule, with no single party able to claim even a relative majority (as a reminder, the EPP, which would remain the largest force in numerical terms, only has 1/4 of the Parliament’s members).

III. EUROPEAN INSTITUTIONS GO BEYOND JUST THE PARLIAMENT

At best, Parliament is only a co-legislator, never the sole decision-maker. In the complex balance of European institutions, the decisive player remains the Council and its Member States.

• Some populist forces are represented in the European Council through heads of government directly from their ranks (Italy, Hungary) or whom they support in coalitions (Sweden, Czech Republic). However, they remain a minority in the European Union’s main decision-making body;

• On most issues, some take a pragmatic approach that doesn’t hinder the functioning of the institutions, (the only instances of complete blockage have arisen from Hungary and PiS’s Poland, though without reaching a total breakdown).

Being associated with national governance leads populist representatives in the European Parliament to adopt less extreme positions compared to their counterparts who are in opposition or have no expectation of holding government responsibilities. This trend, already noticeable, may intensify, with representatives from Italy, Sweden, and the Czech Republic eager to moderate their stances by playing a constructive role in seeking a majority.

Parliament’s positions can therefore relatively easily be influenced by national interventions during final negotiations. This is a very unpleasant reality for the Parliament, which tends to downplay it in public debate, but it still heavily influences the European legislative process.

The election campaign period is often marked by exaggeration, particularly given the current crisis context (including the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, uncertainties in transatlantic relations, and socio-economic challenges). Partisan movements capitalize on these anxieties, using them either to galvanize support or to repel voters.

And yet, while the anticipated global electoral surge of « populist » forces raises legitimate concerns, it must also be viewed with lucidity, and without exaggerating its concrete institutional and political implications.

There will be no « populist » majority in the European Parliament. The « populist » forces, even if they gain ground, will themselves remain divided, and if the Parliament were to become « irresponsible », It would quickly be reframed/supplanted in the European decision-making process by the Council.

The only significant risk of paralysis in the European system wouldn’t stem primarily from a surge in « populist » support in European parliamentary elections. Rather, it would result from the rise to power of a genuinely Europhobic force in one of the EU’s major states. A deadlock in the Council would carry far more serious consequences than a mere increase in the number of « populist » MEPs in Strasbourg.

The translation of this document from French to English was executed by Alice Candy.

COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

Document prepared with the assistance of Clément De Caro, Nicola Gaddoni, Éric Garcia, and Alice Le Faucheur.

Download the PDF here.